The Spanish economy’s growth cycle: Constraints and outlook through 2027

Spain’s economy continues to outperform the eurozone average, driven by robust domestic demand and immigration-fueled job creation. Yet, structural weaknesses in housing, fiscal policy, and private investment pose growing constraints as external demand fades.

Abstract: Spain remains Europe’s leading growth engine, with GDP now 10% above its pre-pandemic level and expanding at nearly twice the eurozone average; all without generating macroeconomic imbalances. However, the current cycle, resilient through successive global shocks, is now driven almost entirely by domestic demand, supported by household consumption and a buoyant labour market. Foreign-born workers have accounted for 65% of net new jobs over the past three years, yet their integration is increasingly constrained by acute housing shortages. Private investment also remains subdued, still 5% below pre-pandemic levels in real terms, weighing on productivity. Meanwhile, European funds, which have fuelled public investment, are expected to taper off as the Next Generation programme approaches its end. Under this scenario, Funcas projects GDP growth of 2.9% in 2025, moderating to 1.9% in 2026 and 1.7% in 2027, underscoring the need to boost residential construction and corporate investment to sustain long-term growth momentum.

Introduction

The Spanish economy continues to defy expectations and spearhead growth in Europe. So far this year, GDP has been expanding at an annual rate of 3%, which is more than twice the eurozone average and better than anticipated by Funcas as recently as the July round of forecasting.

The purpose of this paper is to examine under what conditions the current growth cycle could continue in the near future. To that end, it starts from an analysis of the factors that have driven the economy in recent years despite the deterioration in the international environment on account of escalating trade tensions, among other factors (Torres et al., 2025). Based on that analysis, we share Funcas’ projections for 2025-2027, before highlighting the key medium-term challenges and looking at the risks, both upside and downside, implicit in these projections.

Key drivers behind the strong economic performance

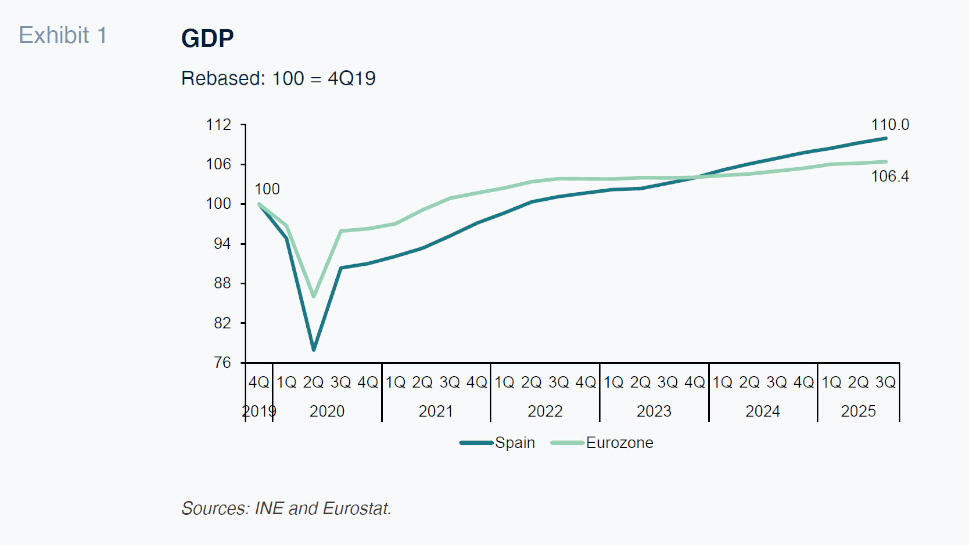

The Spanish economy remains on a clear-cut growth trajectory. Following the INE’s most recent statistical revisions (which yielded an upward adjustment to the growth accumulated in the post-pandemic era), Spanish GDP is now 10% above its pre-pandemic level, compared to an average of 6.4% for the eurozone as a whole (Exhibit 1).

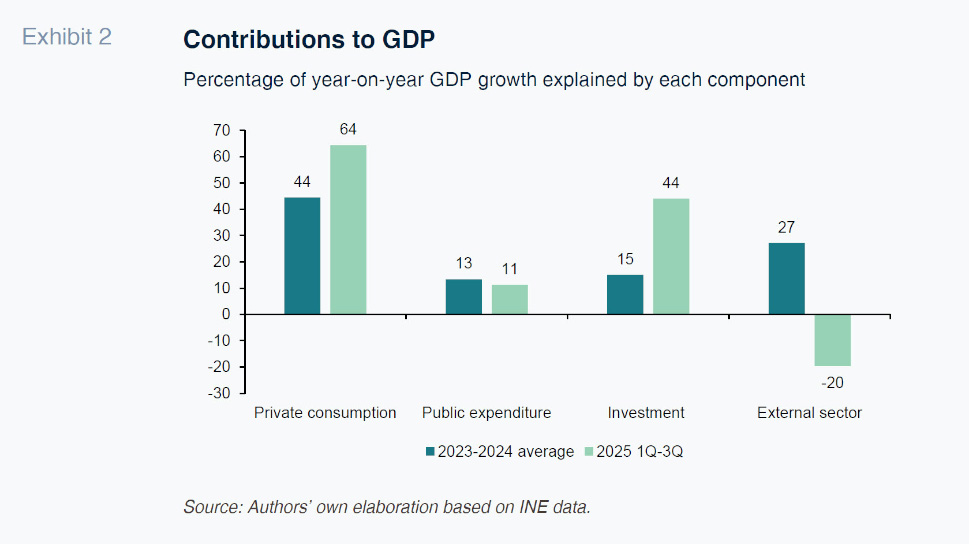

However, despite the continued momentum, the more recent indicators point to a less balanced growth pattern, due to the loss of steam in foreign demand. Indeed, the external sector, whose contribution accounts for more than a quarter of GDP growth in 2023-2024, is now detracting from growth (Exhibit 2).

The inflection is due to a drop in goods exports and a slowdown in tourist arrivals, on the one hand, and faster growth in imports, particularly in products from outside the EU, notably from China, on the other.

[1]

Unlike the external sector, the domestic growth engine remains robust. Household consumption is particularly strong, explaining no less than 64% of the growth in GDP recorded so far this year, which is 20 points more than in the previous two years. Investment has also stepped up its contribution, to 44%, an almost threefold improvement, whereas the contribution by public expenditure has remained stable.

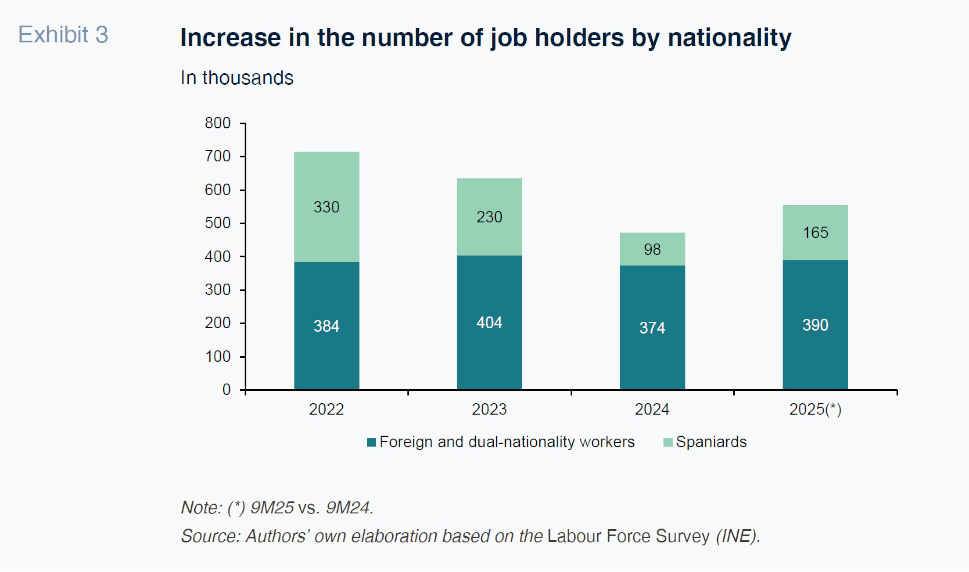

Three key factors underpin the prevailing domestic demand dynamic. First, immigration is enlivening activity in labour-intensive sectors such as construction and hospitality, while contributing to growth in private consumption. By 1 July 2025, the number of immigrants had increased by 602,000 from a year earlier, marking sharp growth, in line with that of the previous three years. According to the Labour Force Survey, 65% of all the net new jobs created between 2022 and 2025 have been taken up by foreign-born or dual-nationality workers (Exhibit 3). In certain sectors, where it is proving harder to find labour, the participation of foreign workers has been even higher. For example, in the restaurant sector, personal, protective and sales services, and in construction, the percentage of newly created jobs held by foreign-born or dual-nationality workers exceeds 80%.

Secondly, investment in housing is reacting to prevailing strong demand and the widespread shortages afflicting the real estate market. Recent indicators point to a sustained recovery in construction, as is also borne out by the national accounts, judging by the 4.8% growth in investment in home-building (with data for the first three quarters).

Thirdly, the need to execute the European funds before the end of the Next Generation (NGEU) programme is fuelling growth in investment (GFCF). In fact, one of the biggest differences in the national accounting statistics for 2022 to 2024 derived from the recent statistical revisions has been a significant increase in GFCF compared to the previously published figures. The adjustment was concentrated in the two components most likely to have benefitted from the European funds: non-residential construction (including civil infrastructure, among other things) and intellectual property products, an area that very probably includes the European funds being channelled into digital transformation.

[2] By contrast, investment in housing and capital goods was revised slightly downwards.

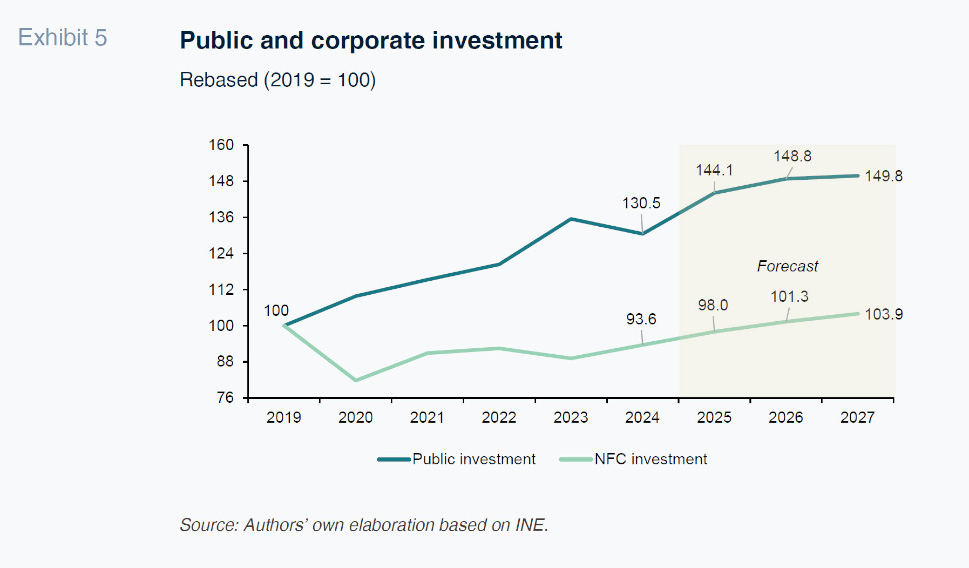

In any case, investment in the bulk of the business sector remains worryingly weak, with only certain (transitory) public assistance targeted at digitalisation providing partial relief. This is evident in the breakdown between investment in the public and private sectors: whereas real GFCF in the public sector was 43% above 2019 levels by June 2025, investment by non-financial corporations (NFCs) continued to lag that same benchmark by 5% (also in inflation-adjusted terms), according to Funcas estimates.

In other words, despite the recent pick up, private investment performance in the wake of the pandemic has been disappointing, especially considering the volume of aid coming in via the NGEU funds and the Spanish economy’s overall buoyancy. Spain is one of the laggards in the EU in this respect (among the countries for which these figures are available), although there is huge cross-country disparity. For example, real corporate investment is down 11% from 2019 levels in Germany, whereas it is up 41% in Greece.

Although we do not have data concerning the composition by asset type for each institutional sector, the figures suggest that the reduction in corporate investment relative to pre-pandemic levels is the result of a contraction in investment in capital goods, in parallel to significant growth in investment in intellectual property products. This disparity could be interpreted as a move among corporations towards more digitalised productive processes or the start of a shift in the economy’s sector mix towards higher-tech activities. However, as already noted, the sharp growth in investment in intellectual property products is closely related with certain specific programmes funded by the European funds (e.g., the so-called Digital Kit) and may, therefore, prove temporary.

On the other hand, it is also true that certain cutting-edge sectors, where investment materialises primarily in technology, may be experiencing strong momentum, which would also be consistent with the extraordinary growth observed in non-tourist service exports in recent years.

The short-term outlook is positive overall…

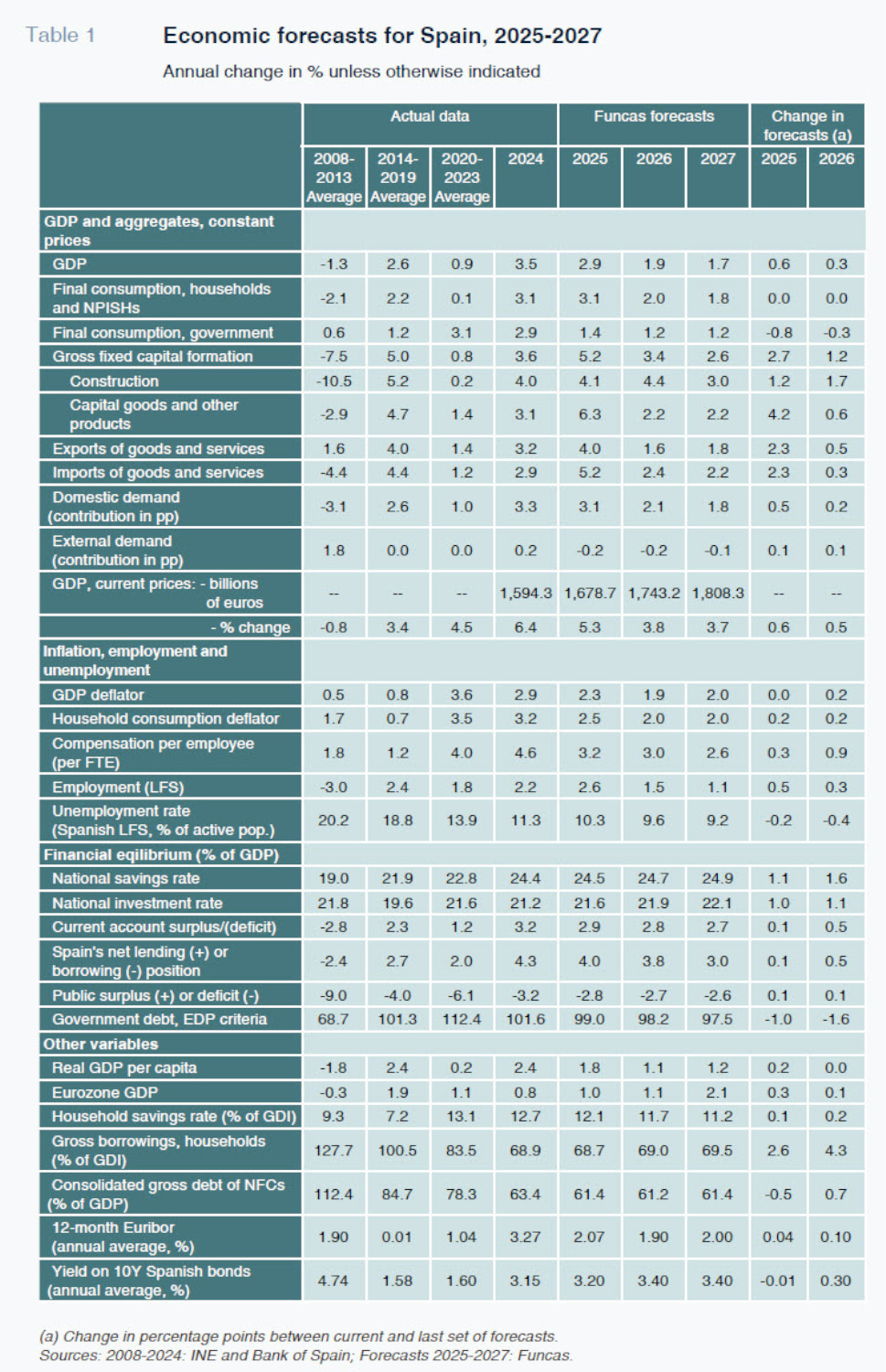

We have revised our forecast for Spanish growth upwards as a result of the recent statistical fine-tuning by the INE and the strength of domestic demand, which is proving more robust than anticipated in July. We are now predicting GDP growth of 2.9% this year (Table 1), up 0.6 points from our last set of forecasts, an adjustment that primarily mirrors the strong momentum being displayed by the Spanish economy and, to a lesser degree, the trade agreement between the EU and U.S., which features lower tariffs than originally feared. As a result, the Spanish economy will continue to be one of the fastest growing in the EU.

That growth will come exclusively from domestic demand, which is expected to contribute 3.1 points to GDP growth. Within domestic demand, investment is now expected to be stronger. The contribution by private consumption is unchanged with respect to our last forecasts, while public consumption is now predicted to contribute a little less. The growth in investment in construction should continue to gather pace, in both the residential segment and in “other construction”, a segment which includes infrastructure and other projects driven by government. Accelerated execution of the European funds should also manifest in investment in capital goods.

The external sector, meanwhile, is forecast to detract from GDP growth by 0.2 points in 2025, which is less adverse than originally anticipated: the tariffs levied on European products by the U.S. are lower than contemplated in the last set of projections.

The economy is expected to slow in 2026 and 2027, as a result primarily of a slowdown in tourism, in public investment (as the European funds gradually wind down) and in private consumption, as the lift from immigration potentially loses steam. In this respect, we are forecasting a slowdown in immigration in the next few years on account of the difficulty of finding housing. Specifically, the economically active foreign population is expected to increase by 875,000 people between 2025 and 2027, compared to 1,080,000 in the previous three-year period. Nevertheless, GDP is still expected to grow by 1.9% in 2026, up 0.3 points from our previous estimate, thanks to the momentum carried over from this year. Domestic demand will remain the main engine, contributing 2.1 points, with the external sector detracting 0.2 points. Private consumption is forecast to slow, in line with slower growth in the labour force and persistent difficulties in finding somewhere to live in the more dynamic markets. Investment is likely to suffer from the looming end of the European funds, partially offset by ongoing momentum in the construction sector.

In 2027, we are predicting GDP growth of 1.7%, which would still be above the European average but closer to the Spanish economy’s potential. The slowdown is attributable to weakness in some of the factors that have been propping up the economy, including tourism, fiscal expansion and population growth. The private sector should, however, remain in good health in terms of both competitiveness and leverage and Spain is expected to continue to present a significant current account surplus.

Inflation is forecast at around 2.5% this year, due to price pressure from food products and services. Euro appreciation, coupled with the assumption that energy prices will remain at relatively reasonable levels, should ease imported inflation in the coming quarters, so that CPI should converge towards the ECB’s target of 2% in 2026, where it should remain also in 2027.

The Spanish economy is expected to create close to 550,000 net new jobs until the end of 2027, which would imply an unemployment rate of 9.2%, the lowest level since 2007. To bring unemployment further down, Spain needs to tackle outstanding challenges in the labour market, particularly the transition by young adults into employment, getting the unemployed back to work and the housing crisis.

… but Spain faces three main challenges in the medium term

Despite the prospect of relatively strong growth in the short term, economic policy space in the event of possible shocks will remain tight as a result of still-high public debt. Correcting the country’s fiscal imbalances, therefore, remains a major challenge. Although the deficit is expected to come down to 2.8% of GDP this year, the improvement is largely cyclical, as it derives from the uptick in tax revenue induced by the prevailing growth momentum. In a context of economic slowdown and in the absence of adjustments, correction of the current fiscal imbalances will be limited in the next few years. [3] Even if the budget continues to be rolled over, which in theory should contain spending, past experience suggests that momentum in the key fiscal metrics continues. As a result, we are forecasting only a slight reduction in the public debt ratio to 97.5% of GDP at the end of the projection period.

Another of the key challenges emerging from these forecasts relates to the housing market. The recovery predicted in construction will barely make a dent in the ongoing housing crisis (Exhibit 4). As a result, if housing supply does not start to rise faster than we are forecasting, the scarcity will constrain labour mobility and growth in the medium term, in addition to having major negative consequences on social wellbeing.

[4]

Lastly, the weakness in corporate investment is another outstanding issue, one that could curb productivity and, by extension, the scope for lifting the country’s living standards. The current projections are consistent with a recovery in investment by non-financial corporations, though barely enough to revisit pre-pandemic levels as from next year (Exhibit 5).

Upside and downside

There is room for stronger than expected growth, given ongoing trends in the labour force and in household consumption. Foreign worker arrivals could be stronger than anticipated in these forecasts, which would stimulate consumption and activity in the sectors where labour is in higher demand. In addition, there is some uncertainty around the sustainability of the current savings rate, which at 11.5% remains well above the levels considered normal a few years ago. This shift may be partly structural, shaped by factors such as immigration or the need to save more to purchase a home. We are forecasting a slight reduction in the savings rate in the coming years, in line with this assumption. However, if surplus savings were depleted faster than forecast, consumer spending would receive a boost.

There are also downside risks, the main one lying with the impact of U.S. economic policy. On the one hand, the trade “agreement” sealed with the EU contains many shades of grey and its application is subject to geopolitical ups and downs. On the other hand, tariffs will continue to permeate the U.S. economy as they are passed through to prices, with negative consequences for household consumption, inflation and the prospect of a sharp correction in interest rates. The prospect of deteriorating public finances will also shape the Federal Reserve’s thinking and actions.

Lastly, high debt burdens, in the U.S. as well as on this side of the Atlantic, coupled with higher spending on defence and political resistance to tackling deficit adjustments, could generate tensions that end up translating into financial market turbulence. In general, economic, financial and trade-related risks with global reverberations persist, with the potential of further eroding the external sector’s contribution to the Spanish economy.

Notes

The exchanges between the Spanish economy and its main trading partners are addressed in Torres (2025).

The former increased by 16.4% over the three-year period, rather than the initially estimated 4.6%, while the latter, which encompasses investment in software, databases and R&D, increased by 28.6% instead of 10.5%.

The persistence of the public deficit is analysed in detail in Torres et al. (2024).

Policies for tackling the housing crisis were addressed by Carbó (2024).

References

CARBÓ VALVERDE, S. (Coord.). (2024).

Mercado inmobiliario y política de la vivienda en España [The property market and housing policy in Spain]. Estudios de la Fundación, No. 104.

https://www.funcas.es/libro/mercado-inmobiliario-y-politica-de-la-vivienda-en-espana/TORRES, R. (2025). The Spanish economy and the rise of trade blocs.

Spanish and International Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 14, No. 5 (September 2025).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/Europe-between-geopolitical-shocks-and-economic-weaknesses/The-Spanish-economy-and-the-rise-of-trade-blocsTORRES, R., FERNÁNDEZ, M. J., and GÓMEZ DÍAZ, F. (2024). Outlook for Spain’s economy and public finances: 2024-2025.

Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook, Vol. 13, No. 6, (November 2024).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/Spain-and-Europe-in-an-era-of-policy-uncertainty/Outlook-for-Spains-economy-and-public-finances-2024-2025TORRES, R., FERNÁNDEZ, M. J., and GÓMEZ DÍAZ, F. (2025). The Spanish economy in the face of the trade war.

Spanish and International Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 14, No. 3 (May 2025).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/pdf/Torres%2014-3.pdf

Raymond Torres, María Jesús Fernández and Fernando Gómez Díaz. Funcas