The Spanish economy and the rise of trade blocs

The global economy is increasingly shaped by geopolitical blocs, reflecting the weakening of multilateralism. Spain has been resilient to this disruption thanks to its strong competitive position with other EU countries; but, this hides structural export weaknesses with non-EU regions, notably the U.S. and China, underscoring the need to revitalize the single market and boost investment.

Abstract: Globalization has undergone significant changes in recent years, particularly since the start of President Donald Trump’s second term. World trade and international investment are increasingly following a bloc-based logic, underscoring the weakening of multilateralism. In this context, the Spanish economy has managed to maintain a significant external surplus, although this result masks two contrasting realities. On the one hand, the trade balance with the EU has improved, thanks to gains in competitiveness vis-à-vis EU partners, thereby offsetting the sluggishness of the single market. Between 2019 and the first quarter of 2025, Spanish exports of goods and services to the EU increased by 49%, a rate higher than that recorded by Germany, France, and Italy. On the other hand, the balance with the U.S. and China has deteriorated sharply, particularly since the start of the trade war, as a result of structural weaknesses of the Spanish export model. Spain imports around €45 billion from China, six times more than the €7.5 billion it exports, highlighting the scale of this imbalance. All of this requires revitalizing the single market, strengthening the EU’s negotiating capacity, and creating favorable conditions for investment in Spain.

Introduction

The shift in trade policy undertaken by the Trump administration upon taking office at the beginning of the year is shaking the foundations of globalization, understood as a process of economic integration between countries. In addition to raising tariffs to levels not seen since the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions in the last century, the measures imposed by the world’s leading power are altering the foundations of the global economy, allowing power asymmetries to prevail over comparative advantage, the latter being a guarantee of greater economic benefits for all countries. [1]

The U.S. tariff offensive, however, has been preceded by multiple signs of a weakening multilateral system. International trade has tended to become "regionalized," meaning that integration has deepened within geopolitical blocs. The number of regional agreements has increased sixfold in the last 25 years, leading to a fragmentation of the system.

[2] More recently, the WTO itself has lost its capacity for action due to the quasi-paralysis of its dispute settlement mechanism. On the other hand, the struggle for technological leadership has intensified, leading to a growing number of trade restrictions, particularly since the pandemic.

[3]

The aim of this paper is to examine how these changes have altered the position of the Spanish economy over the last five years, both within the European Union, the trading bloc in which it is embedded, and in relation to the rest of the world.

A favorable competitive position of Spain in the shrinking European market

Various studies point to the reconfiguration of supply chains, particularly since the pandemic (Blanga-Gubbay & Rubínová, 2023). Many companies have opted for "friendshoring" strategies, relocating production to allied or geographically close countries to reduce risks in an increasingly tense international context. Hence the importance of analyzing the evolution of Spain’s position within the single market, the trade bloc of which it is a part.

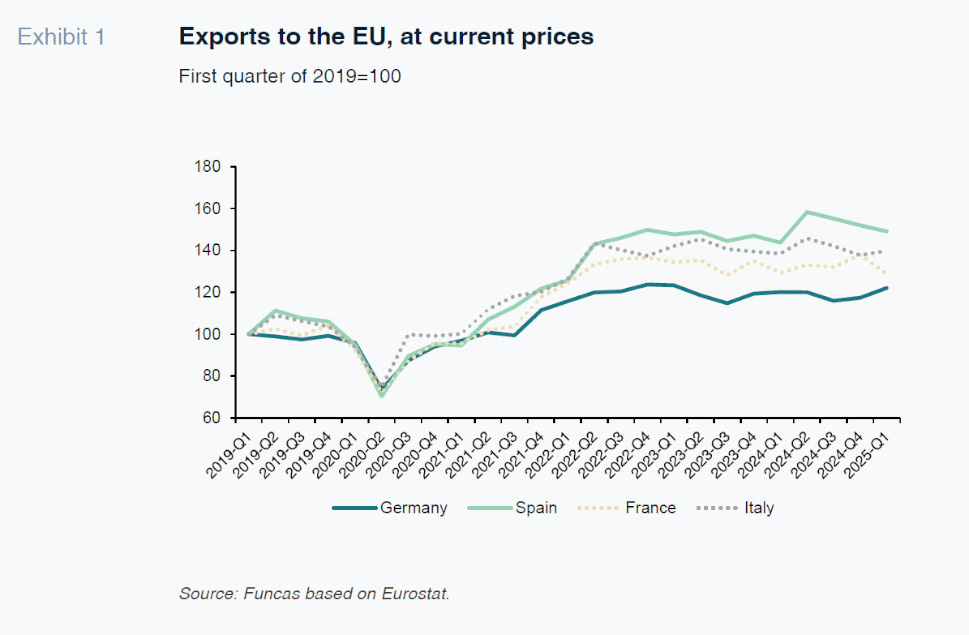

In this regard, the data show a positive trend: Spanish exporters have gained market share in the EU over the last five years. Between 2019 and the first quarter of 2025, the value of total exports of goods and services to the EU increased by 49%, a much better performance than Germany, France, and Italy (Exhibit 1). The trend is also favorable in the goods segment, although the increase is smaller (+ 37%) and there has been a slight decline in the last year. In the case of services, growth is more intense (+92%) and does not appear to have been interrupted despite the recent slowdown in tourism, highlighting the strength of non-tourism services.

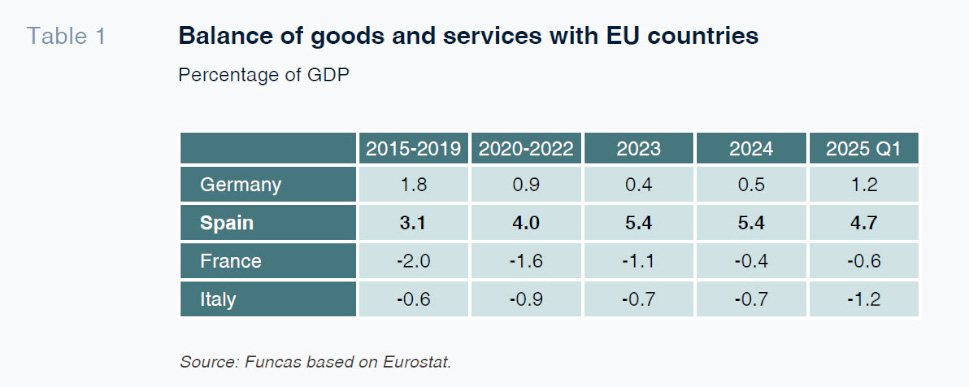

On the other hand, as imports have grown less than exports, the trade balance with the EU shows a growing surplus, rising from 3.1% of GDP, in the period 2015-2019, to 5.4% in 2024, a figure that remains virtually unchanged according to the information available for the first quarter of this year. By comparison, the trade surplus between Germany and the EU has tended to decline, while France and Italy have posted deficits (Table 1).

Low relative production costs have contributed to the strength of the Spanish surplus with the EU, boosting exports and reducing the elasticity of imports with respect to domestic demand.

[4] Labor costs fell during the adjustment period following the financial crisis, and the differential with respect to the main EU partners has remained largely unchanged in the recent period. On the other hand, the moderation of energy costs, in relative terms, since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine has added to competitiveness, helping to explain the improvements in market share in the EU.

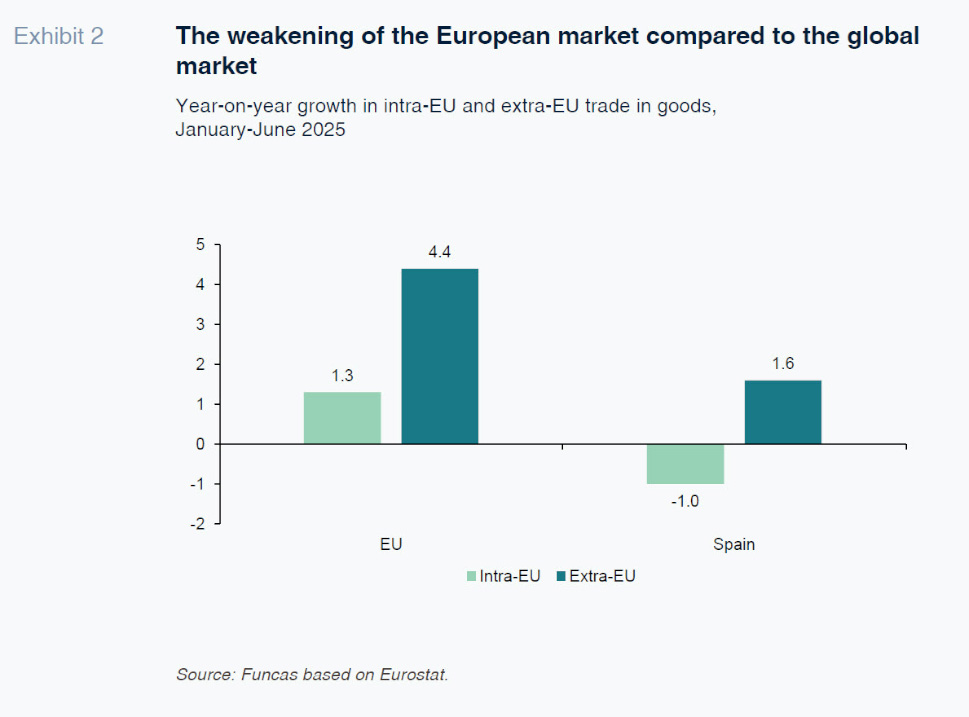

Although the results in Europe for the Spanish export sector are positive, the diagnosis must be qualified considering developments in the single market, as the European economy is experiencing very weak growth, which in itself tends to weigh on intra-European trade. In addition to weak demand, the persistence of barriers to trade and investment, together with the increase in state aid, are additional factors contributing to fragmentation.

It is a fact that intra-European trade has grown less than trade with the rest of the world, particularly in the most recent period (Exhibit 2). In the first half of this year, intra-European trade in goods grew by a meager 1.3% compared to the same period last year. This is 3.4 times less than EU exports to third countries (extra-EU trade). In the case of Spain, shipments of goods to other EU countries fell by 1% over the same period, while extra-EU exports increased by 1.6%.

Therefore, looking ahead, gains in export market share may be insufficient to offset the sluggishness of the EU economy, exacerbated by the rampant fragmentation tearing apart the single market and the tariff escalation brought about by the recently sealed agreement between the U.S. and the EU. This agreement, in addition to directly affecting exports, could also perpetuate the climate of uncertainty, weigh on investment decisions, and cloud the European outlook.

A quantitative and qualitative deficit of Spain with the U.S. and China

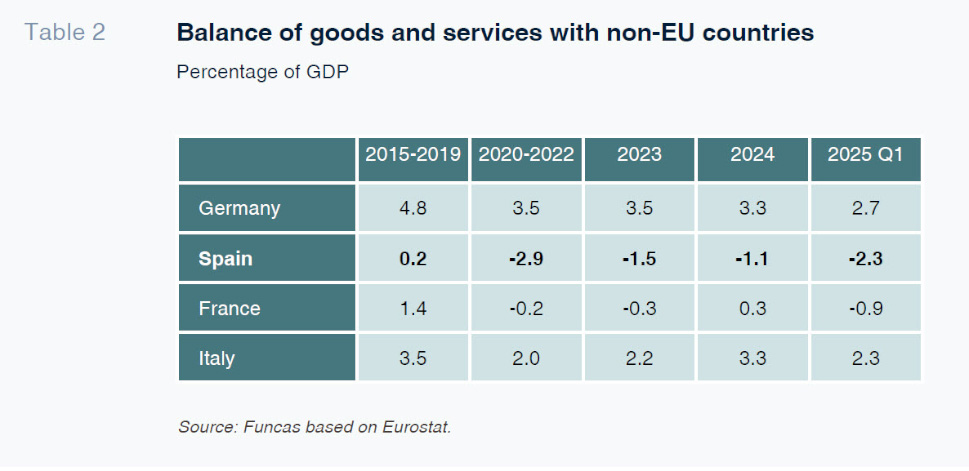

In contrast to the good results achieved in the EU, the Spanish export sector is recording a growing deficit with third countries, a trend that has worsened with the trade war. Over the last five years, the trade balance in goods and services with non-EU countries has remained negative, with a tendency to worsen in the most recent period (Table 2). This deficit contrasts with the surpluses of Germany and Italy, and the fluctuations around balance in France.

On the other hand, the growing imbalance in trade with non-EU countries stems from the goods segment, where exports tend to grow less rapidly than imports, generating a negative balance that has doubled in the last five years to exceed 5% of GDP in the first quarter of this year. Services show a relatively stable surplus over time, close to 2% of GDP, which is however insufficient to offset the deterioration in the goods balance.

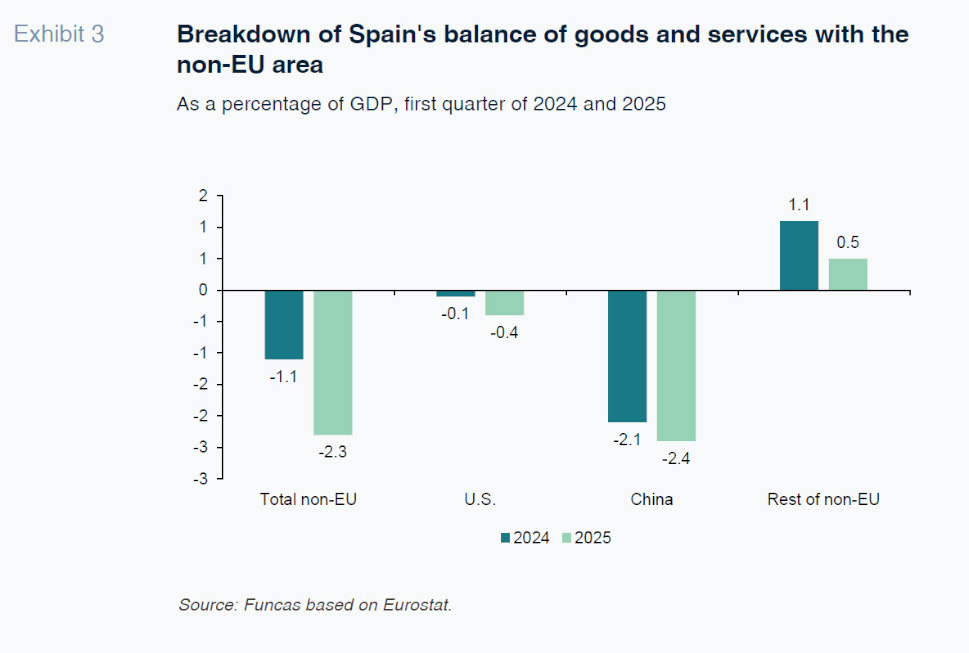

Within the non-EU area, the large and growing deficit of Spain with China stands out (Exhibit 3). Indeed, there appears to have been an intensification of imports from the Asian giant, coinciding with the escalation of the trade war. As for the US, the total balance of goods and services has gone from equilibrium to a deficit position in the first quarter of 2025, reflecting the initial effects of tariffs. In any case, the acceleration of shipments in anticipation of tariff tightening does not seem to have occurred in the case of Spain, at least at the aggregate level. Finally, trade with other third countries shows a positive balance, which is nevertheless tending to decline.

The poorer performance of trade with the non-EU area is also reflected in the composition of trade, particularly with China. Among the most buoyant sectors in Spain exports to China, which amount to around €7.5 billion, are meat products, minerals, copper products, pharmaceuticals, and some machinery. Conversely, Spain buys from China electronic products, machinery, vehicles, organic chemicals, and clothing. Total imports amount to €45 billion, which is six times more than what is exported.

The sectoral pattern of trade with the U.S. seems less pronounced. Spain sells animal fats and minerals, but also electrical machinery, other equipment, and pharmaceutical products (among the five sectors with the greatest weight in exports). The main import products include fuel, aircraft, optical instruments, machinery, and pharmaceutical products. However, differences in specialization are more clearly seen in services: the U.S. digital sector occupies a prominent place in Spain services’ imports, while exports of services to the U.S. are less technology-intensive.

Implications for economic policy

In short, the Spanish economy is not immune to the reconfiguration of globalization that has accelerated in recent times. The maintenance of an external surplus, coupled with sustained GDP growth, is good news, but it masks two disparate realities.

On the one hand, the good results in foreign trade are mainly due to improved export penetration in the EU, the result of a favorable competitive position vis-à-vis other major EU partners. On the other hand, the performance of the foreign sector outside Europe is less buoyant. In addition to the overall deficit with non-EU countries, aggravated by the tariff offensive, the pattern of specialization is not favorable to the Spanish economy.

Looking ahead, the persistent fragmentation of the single market, together with weak demand growth in the eurozone, casts a shadow over the positive outlook for foreign trade. To avoid decline and thus sustain the European engine of growth in the face of global challenges, it is crucial to revive the single market through reforms and joint investment in public goods, as pointed out in the Draghi report. Various studies highlight the benefits for the Spanish economy of reforms inspired by this report (see Torres, and González Simon, 2025).

These imbalances also highlight the importance of investment, a key variable for accelerating technological adaptation, improving productivity, and counteracting the deterioration of the terms of trade in global markets. Although domestic business investment has rebounded in the last three quarters, its level is still insufficient to drive transitions. It is worrying that foreign direct investment, which could compensate domestic weakness, is declining: so far this year (based on data from January to May), FDI inflows have fallen by 32% compared to the same period in 2024 and by 39% compared to 2023. In short, disruptions in world trade highlight the need for a new cycle of reforms and investment, both in Spain and in Europe at large.

Notes

For a historical precedent for the current moment of unilateralism, see Hirschman (1980).

Over the last three years, the elasticity of imports with respect to domestic demand has been below 1, which is lower than the historical elasticity of around 1.2. (see Torres, Fernández, and Gómez Díaz, 2025).

References

BLANGA-GUBBAY, M., and RUBÍNOVÁ, S. (2023). Is the global economy fragmenting? WTO Staff

Working Papers, ERSD-2023-10. World Trade Organization (WTO), Economic Research and Statistics Division.

https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/280428/1/1873031211.pdf HIRSCHMAN, A. (1980). National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. 1

st ed.

JSTOR. University of California Press.

https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.15976659 TORRES, R., FERNÁNDEZ, M. J., and GÓMEZ DÍAZ, F. (2025). The Spanish economy in the face of the trade war. SEFO.

Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook, 14(3).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/Policy-risks-and-fiscal-pressures-Economic-fragilities-in-a-year-of-global-transition/The-Spanish-economy-in-the-face-of-the-trade-war TORRES, R., and GONZÁLEZ SIMON, M. A. (2025). The Draghi Report and the Spanish Economy.

SEFO. Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook, 14(1).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/The-future-of-Europe-and-Spain-under-Trumps-second-administration/The-Draghi-report-and-the-Spanish-economy

Raymond Torres. Director of Economic Analysis and International Affairs at Funcas