The Draghi report and the Spanish economy

Mario Draghi’s report identifies integration as key to addressing Europe’s structural challenges, focusing on, first, the need to rollout a common economic policy and, second, the completion of the EU Single Market. For Spain, the latter measures would be the most effective in unlocking investment, though their success hinges on overcoming fragmentation risks amid rising protectionism.

Abstract: Addressing the risk of a structural decline in the European economy, Mario Draghi’s report on competitiveness presents two complementary solutions, namely: (i) the rollout of a common economic policy along with public investment incentives; and (ii) completion of the Single European Market. While both solutions are particularly relevant for Spain, further European integration would bring greater benefits in the short-term and is also the more feasible solution, considering the state of much of the EU’s public finances. This is because, first of all, greater integration would provide Spain with better access to EU capital markets, thus addressing the current investment deficit, which stems largely from the private sector and a weak public-private investment multiplier. Secondly, more integration could help Spain further improve its competitive positioning within the EU, which has already seen significant gains, driven by relatively cheaper labour and energy costs. This could help offset the lost ground in global markets, particularly in the technology sector. While greater integration would channel European savings into Spain’s productive sector, the biggest risk remains fragmentation among Member States amid the rising tide of protectionism.

Foreword

The European economy’s weak performance, in both historical terms and by comparison with other global economic powers, has sparked debate about the causes of its decline and possible solutions. Against this backdrop, the report on European competitiveness prepared by Mario Draghi at the request of the European Commission President constitutes an exhaustive assessment (European Commission, 2024). The report flags gaps in investment, innovation and technological development as the main impediments. Based on his assessment, the former President of the European Central Bank calls for the reconfiguration of European economic policy: a combination of measures designed to unlock investment, deepen European integration and accelerate structural reforms. Failure to make changes, the report claims, would plunge the European Union (EU) into an existential crisis.

The main goal of this paper is to examine the report’s relevance for the Spanish economy based on its unique situation relative to the rest of Europe. While Draghi’s underlying assessment is by and large shared in Brussels, the Spanish economy presents certain idiosyncrasies that suggest the need to prioritise the report’s recommendations.

Draghi’s assessment

The report’s analysis starts from the observation that the world is undergoing rapid transformation as a result of the technological disruption implied by digitalisation and the advent of artificial intelligence, climate change, deglobalisation and their resulting energy and trade shocks, particularly since the pandemic. In this context, exacerbated by population ageing, the EU faces major challenges.

In recent decades, especially since the financial crisis, economic growth in the EU has been meagre by comparison with other global actors. In 2023, the difference in real GDP, adjusted for purchasing power parity, between the EU and U.S. was a gap of 12%, compared to an excess of 4% 20 years earlier. During the same period, China has tended to converge towards the standards of living enjoyed in Europe.

According to the report, around 70% of the shortfall in per-capita GDP with the other side of the Atlantic is attributable to the productivity gap. The remaining 30% is explained by the deficit in active population, an issue set to worsen considering the demographic forecasts for Europe.

The main reason for such low productivity is the shortfall of investment in the EU, prompting the Italian central banker to recommend increasing investment by around 800 billion euros per annum, which is equivalent to roughly five percentage points of the EU’s annual GDP. By comparison, investment under the Marshall Plan was equivalent to 1-2% of the region’s annual GDP.

Draghi maintains that Europe has abundant financial resources to deal with this huge investment effort. The household savings rate is high, at least by comparison with the U.S., and the region presents a consistent current account surplus, evidencing the persistence of excess savings. The way forward would thus be to mobilise these funds, which are currently exported to third countries, particularly the U.S., rather than being invested productively in Europe.

Several factors lie behind this outflow of capital. The first is capital markets fragmentation, which leads Draghi to call for the creation of the Capital Markets Union, so as to channel excess savings into strategic projects. The recommendations include creating a single market regulator and regulatory standardisation, among other things.

Another obstacle is over reliance on bank financing. European banks face strict regulations, higher costs and smaller scale than their American counterparts, limiting their ability to assume the risks associated with large-scale innovation projects. The report recommends boosting the banks’ funding capacity by developing the Capital Markets Union and completing the Banking Union.

The small size of European enterprises as a direct consequence of Single Market fragmentation constitutes an additional obstacle. Further integration of the markets for goods, services, people and capital is essential to fostering investment in the EU as it would lift businesses’ growth potential and stimulate innovation.

Lastly, the report calls for a step-up in public investment, if possible, jointly orchestrated under the umbrella of a common industrial policy. The analysis flags the relative inefficient channelling of public funds. Despite the existence of ample resources at the European level, their impact is curtailed by the excessive complexity and red tape involved in obtaining them and a lack of alignment around strategic priorities. All these obstacles signal the lack of a genuine European economic policy.

Reforms are needed to enhance the multiplier of public spending on private-sector investment. Measures on the revenue side would also help, e.g., by strengthening tax rules conducive to productive investment. The prospect of higher productivity gains would create fiscal space for these initiatives: the report’s authors believe that the short-term impact on the budget of investment-friendly measures would be offset in the longer-term by its positive effects on productivity. [1]

The Draghi report presents an exhaustive assessment of the state of the EU economy and proposes economic policies for raising investment and productivity, thus boosting the region’s competitiveness. Ultimately, the goal is to improve the investment climate, accelerate decarbonisation and increase economic autonomy. The report identifies three types of policies for attaining these goals: increasing Europe’s public investment effort under the scope of an economic policy that coherently combines industrial, technology and competition policy; completion of the Single Market; and governance reforms.

Relevance of the assessment for Spain

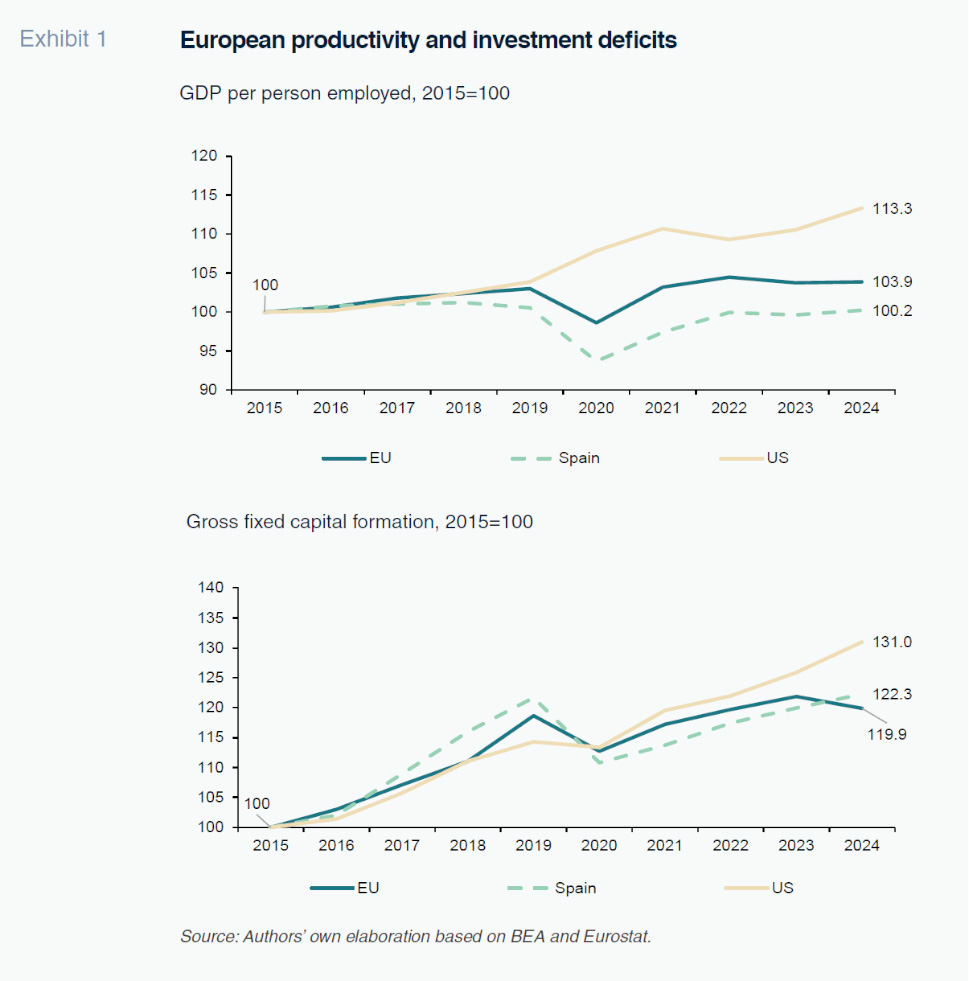

The key trends identified in the Draghi report for the EU as a whole generally apply to Spain. Spain enjoys high economic growth relative to the rest of Europe. However, that growth is mainly driven by incorporating more workers into the economy, and not by increasing productivity. Indeed, little progress has been made in terms of GDP per employed person: the flagged weakness in European productivity relative to its main competitors, primarily the U.S., is more pronounced in Spain. GDP per person employed lies slightly below the level observed in 2015, compared to slight growth in the European average and sharp growth in the U.S. (Exhibit 1). The conclusion that ground has been lost also holds, albeit a little less forcefully, if productivity is measured per hour worked (shaped primarily by the upward trend in part-time work). The latest productivity figures are ticking up, although not yet enough to suggest a structural turnaround.

The aggregate European data paint a picture of a productive sector finding it hard to adapt to the transformations underway in technology, energy and trade. The automotive sector is a case in point (Torres, 2024). Historical evidence shows that increased investment is a prerequisite for surmounting the risk of structural stagnation. However, investment is one of the variables to have lagged the most during the recent expansionary period. Since 2019, investment (gross fixed capital formation) has increased a mere 0.5% in volume terms (discounting the movement in the investment deflator and comparing the first three quarters in both years), and by 1% in the EU as a whole. In the U.S., total investment has increased by 14.6% over the same period, lending support to the conclusion reached in the Draghi report that Europe’s underperformance is largely attributable to its scant investment in equipment and technology.

To evidence these structural challenges, the Draghi report points to the ground lost by Europe’s companies in global markets. The EU remains a net exporter at the global level, but its market share has been shrinking. Goods exports from the EU to the rest of the world (excluding intra-EU trade) have decreased to 14.3% of total global trade, down one point from 2019. Over the same period, U.S. exports have also lost market share, albeit somewhat less so (half a point less), while China has increased its presence (by one full percentage point).

The EU’s trade balance continues to present a significant surplus, which merely reflects lethargic imports in a context of weak internal demand. Moreover, Europe’s decline is particularly eye-catching in burgeoning sectors associated with the double digital and green transition, a concern for future competitiveness considering the extension of artificial intelligence. According to recent estimates, European presents a structural deficit in its trade in products associated with green energy. [2] And in the case of high-tech products, the trade balance has swung from a surplus to a deficit. [3]

Specifics of the Spanish productive model

While the Draghi assessment is applicable to the Spanish economy, there are also idiosyncrasies of major policy significance.

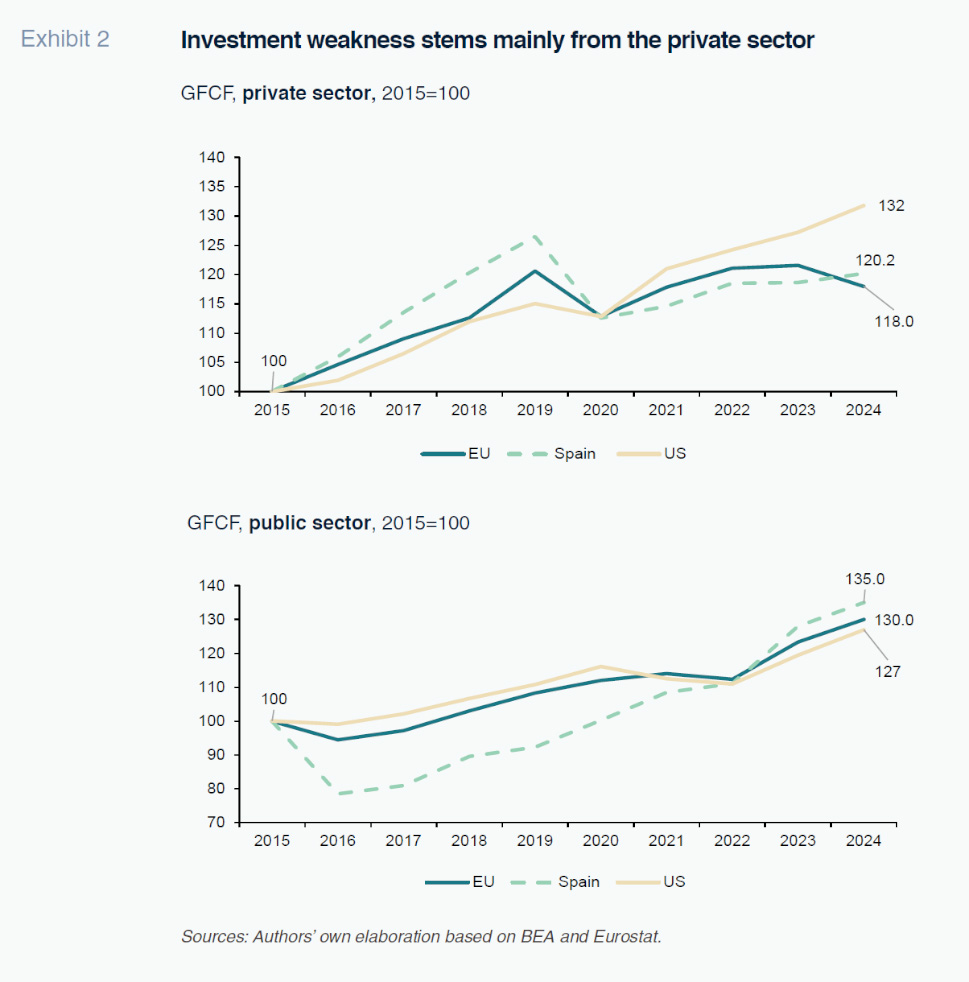

First of all, in Spain the investment gap originates almost entirely from the private sector. Since 2019, private investment has decreased, while public investment has increased intensely (Exhibit 2). In the EU, the divergence between the two sectors has been less pronounced than in Spain. And, in the U.S., growth in private sector investment has kept up with the effort made by the public sector, evidencing a high multiplier effect.

Private investment in Spain would have been expected to be stronger. Demand, one of the key determinants of investment according to empirical evidence, has been on a sharp upward trend over the past four years. Likewise, Spain’s corporations are in relatively good financial health, presenting ample surpluses. Their total debt has fallen back to the lows last seen early this century, before the formation of the credit bubble. And still the corporate sector continues to pile up financial savings or reduce liabilities rather than reinforce productive capacity.

The availability of European funds under the scope of the NGEU programme also foreshadowed a swift recovery in private investment, by lowering the cost of capital. Instead, European funds have materialised mainly in public sector investment without in turn stimulating corporate investment. The small multiplier effect may be partly attributable to the context of rising interest rates, and its corollary in terms of higher returns on financial assets relative to expected returns on productive investments. However, the same phenomenon happened in other countries, without having the same harmful effect on investment.

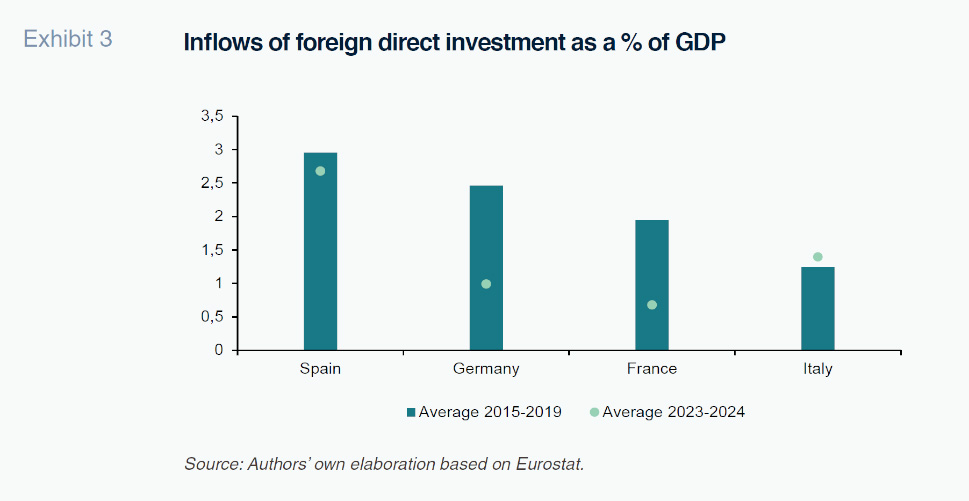

Secondly, the deficit of private investment has a nationality bias: the companies less inclined to invest are the Spanish ones, particularly the small businesses that account for the bulk of the country’s economy. In contrast, foreign direct investment (FDI), which generally hails from large international corporations, has increased relative to the levels observed before the pandemic, while total private investment has narrowed. In the last two years, the inflow of FDI has averaged 3% of GDP per annum, which is more than twice the volume received by other major European economies relative to the size of their economies (Exhibit 3). Market services, notably technology- and telecommunications-related activities, are major recipients of FDI inflows (garnering 57% of the total in 2019-2023). Manufacturing, electricity supply and energy sectors also rank among the top recipients, receiving proportionately more funds than their share of GDP: the manufacturing sector accounted for 34% of total FDI during the same period.

Most of the FDI inflows (roughly 60% in 2019-2023) consist of new injections of productive capital, either greenfield operations or expansions of existing capacity, therefore contributing directly to the investment effort. The remainder consists of acquisitions, whose impact on investment at the recipient companies is more diffuse or uncertain.

Spain’s largest corporations have also tended to offshore some of their productive capacity, making significant direct investments abroad, similar in size to the funds received. In net terms therefore, subtracting the outflows from the inflows, the flow of productive capital has been close to zero, in contrast to the trend observed for the EU as a whole, where outflows have significantly outpaced inflows. During the first three quarters of 2024, the EU exported 269 billion euros of capital to third countries, evidencing the obstacles to mobilising pent-up savings and channelling them into productive assets in Europe.

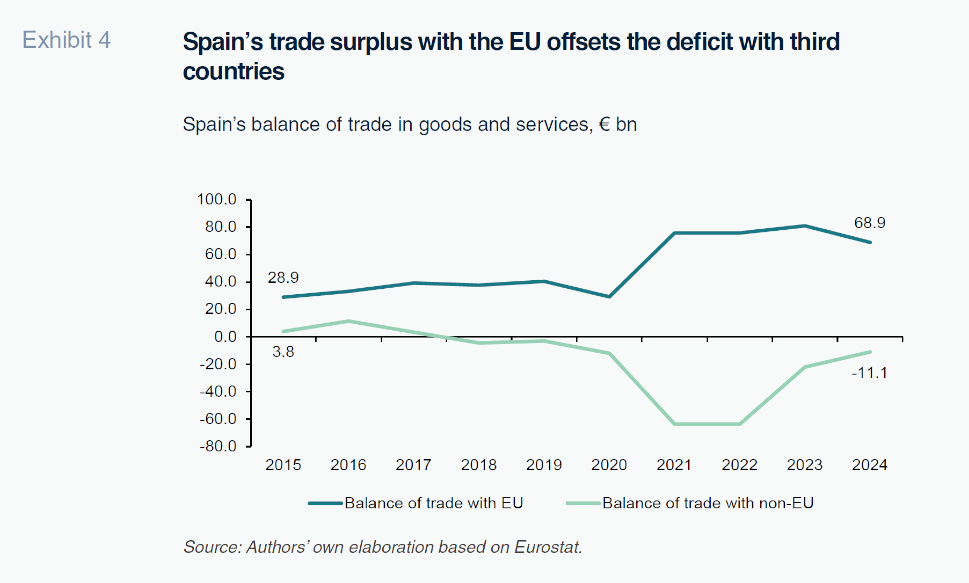

Thirdly, the loss of international market share has been mitigated in Spain by considerable growth in trade with other European partners. The value of the goods and services exported by Spanish companies to the rest of the EU is significantly higher than the value of the goods and services imported from those same economies, generating a surplus of close to 80 billion euros in 2023, which is nearly twice the pre-pandemic surplus (Exhibit 4). The 2024 surplus is expected to be even bigger judging by the data already available for the first three quarters. This surplus more than offsets Spain’s trade deficit with non-EU countries, leaving it with a considerable overall trade surplus.

By comparison, the other large European economies present a deficit or shrinking surplus relative to their pre-pandemic positions. For example, Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal and the Scandinavian countries report a persistent or growing deficit in their intra-EU trade. Germany, meanwhile, has seen its intra-EU surplus fall to half the level observed before the pandemic.

The improvement in Spain’s trade position relative to its European partners stems from its strong performance in both services and goods, the latter in spite of a quasi-industrial crisis. In both instances, the trade surplus is trending upwards, signalling improved competitiveness relative to the EU.

The step change in non-tourism services not only cements the overall performance but also reveals diversification of the productive model, reducing Spain’s dependence on long-standing pillars such as tourism, retailing and construction. Despite this diversification, however, the growth model continues to be characterised by scant productivity gains, in line with its additive nature: GDP is growing largely supported by increases in the labour force, which is not translating into a substantial improvement in productive efficiency.

As for labour costs, Spain’s competitive advantage already became clear during the 2010s. Between 2010 and 2019, unit labour costs held steady (dropping during the sovereign debt crisis, followed by a slight recovery), compared to growth of close to 10% across the EU. This competitive advantage, a key factor behind the improvement in Spain’s foreign accounts, has survived the last few years relatively unscathed. However, it is worth recalling that the reduction in unit labour costs came from squeezing wages and not productivity growth.

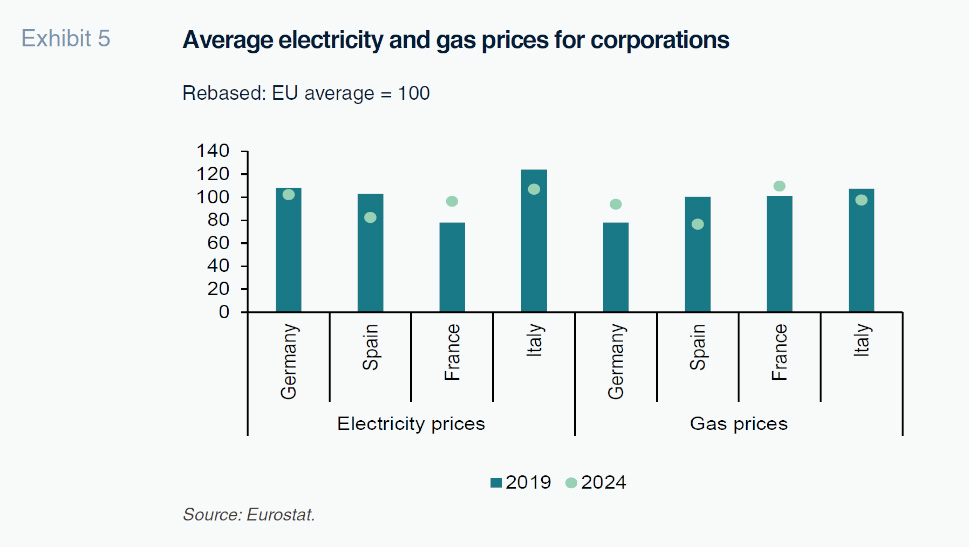

Energy costs have also fared well by comparison with neighbouring economies (Exhibit 5). In the last five years, electricity prices for Spanish corporations have increased by 22%, and gas prices by 39%, which in both cases is less than half of the European averages. The deployment of renewable energy and availability of an ample infrastructure of liquefied gas processing help explain the relative improvement in energy prices, further cementing the country’s competitive advantage in terms of productive costs and kindling investments by foreign companies.

So which of Draghi’s recommendations should Spain prioritise?

In sum, this analysis confirms the relevance of the assessment made in the Draghi report, particularly as it concerns the investment and productivity gaps and the productive sector’s difficulties in adapting for the major unfolding technology and trade challenges.

However, we also highlight some important idiosyncrasies of the Spanish productive model that should be taken into consideration in the European economic policy debate. Firstly, Spain’s investment deficit stems above all from the private sector and not a shortfall of public resources, which remain relatively abundant. The public-private investment multiplier is worryingly weak. Secondly, the lost ground in global markets, particularly in the technology sector, is being offset in Spain by a sizeable improvement in its competitive positioning within the EU, shaped by cheaper labour and energy costs.

This means that the priority for the Spanish economy should be completing the Single Market as the main driver of growth. A step in the direction of Capital Markets Union would help channel European savings into the Spanish productive apparatus, considering its advantageous competitive positioning in Europe. Elsewhere, rather than a sharp increase in public investment, which is already at record levels, what the Spanish economy needs is to reinforce the linkage between public and private investment. In this sense, the Draghi report correctly calls for strengthening European integration and articulating a common European economic policy to tackle the key challenges. The biggest risk is fragmentation in light of the protectionist threat emerging on the other side of the Atlantic.

Notes

The report refers to an increase in total factor productivity of 2% over a ten-year horizon thanks to the growth in public investment, whose budget cost would therefore be offset in the medium-term by higher tax revenue.

References

Raymond Torres and Miguel Ángel González Simón. Funcas