The Spanish economy in the face of the trade war

The escalation of U.S. tariffs is weighing on the global economy, with Spain facing limited direct exposure but significant indirect risks. As protectionism deepens and uncertainty persists, exports and investment are expected to slow, thus weakening growth; however, the outlook remains relatively positive.

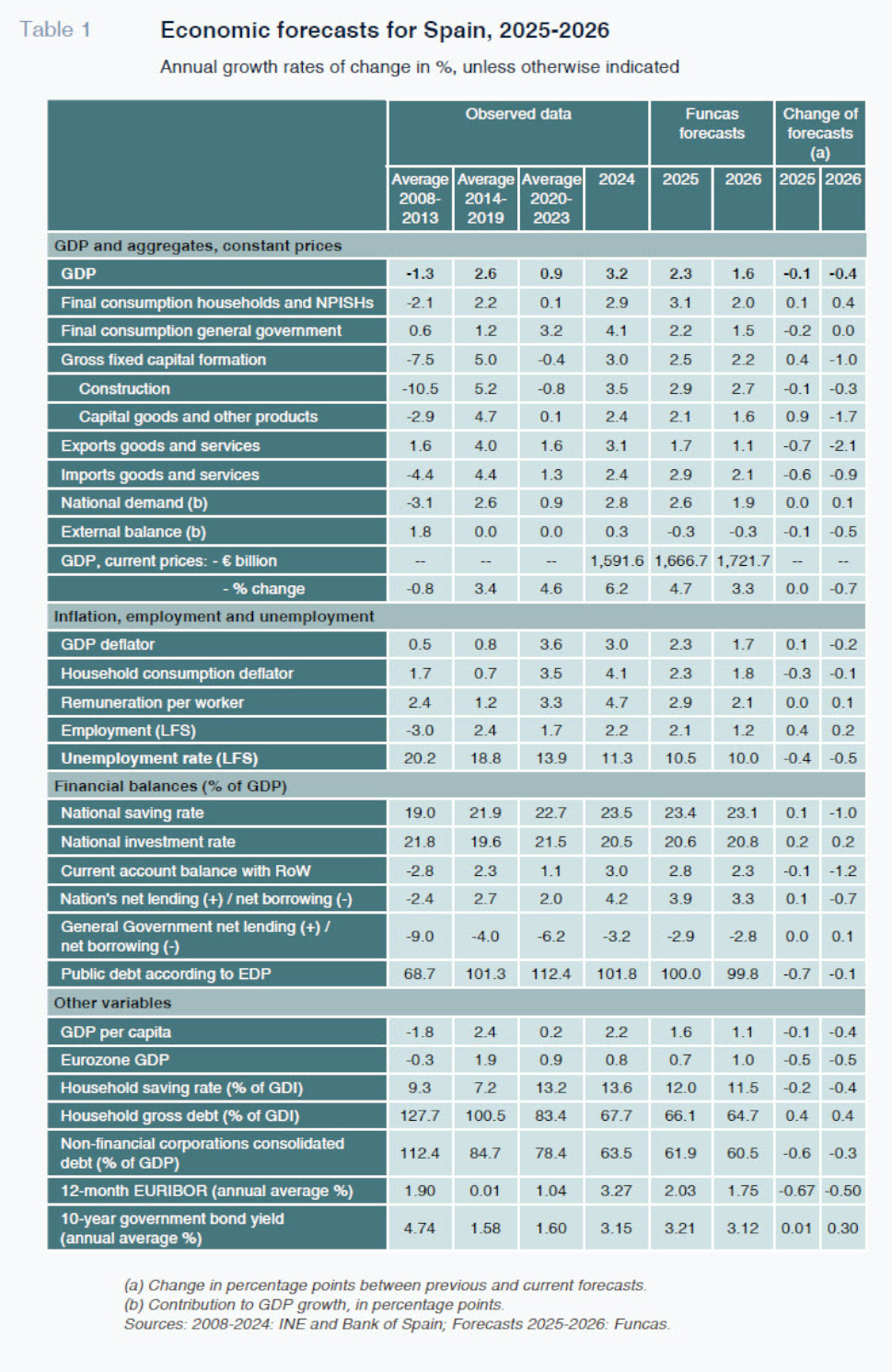

Abstract: The tariff measures announced by Washington on 2 April ushered in a period of heightened uncertainty for the global economy, while simultaneously signaling a potential inflection point for the multilateral trading system. Although the direct impact of the tariffs on the Spanish economy is relatively limited –with an estimated GDP loss of 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points– the burden is disproportionately borne by a small number of sectors. Moreover, the indirect effects are expected to be more pronounced. First, countries heavily affected by the tariffs, such as China, are likely to redirect exports toward alternative markets, potentially increasing competitive pressure on European imports. Second –and most critically– the adverse effects on U.S. economic activity, financial markets, and particularly investment, which is closely tied to trade flows, will play a significant role as the escalation of tariffs and retaliatory measures persists. Under relatively benign assumptions, the Spanish economy is projected to grow by 2.3% in 2025 —0.3 percentage points below pre-conflict estimates— and by 1.6% in 2026, reflecting a 0.4-point downward revision.

Introduction

Since Donald Trump’s return to the U.S. presidency, the multilateral trading system has entered a new phase of instability, the implications of which are examined in this article. On 2 April –referred to as “Liberation Day” by the administration– the U.S. government implemented sweeping tariff measures, while leaving open the possibility of further restrictions, including so-called reciprocal tariffs. Since then, a string of announcements and counter-announcements, as well as specific agreements with the United Kingdom and China, have done little to dispel the prevailing uncertainty.

For the Spanish economy, the starting point remains favorable due to the expansionary momentum of recent years. GDP grew by 3.2% in 2024, significantly above the European average and exceeding earlier expectations, thanks largely to strong external sector performance. Growth persisted in early 2025, with GDP expanding by 0.6% in the first quarter –just 0.1 percentage points below the previous two quarters– prior to the imposition of tariffs. However, this may partly reflect a temporary surge in exports, as firms anticipated and pre-empted protectionist measures. The full impact of the trade war is therefore expected to manifest more clearly in the coming months, as detailed in this paper.

Tariff escalation and its expected impact in 2025-2026

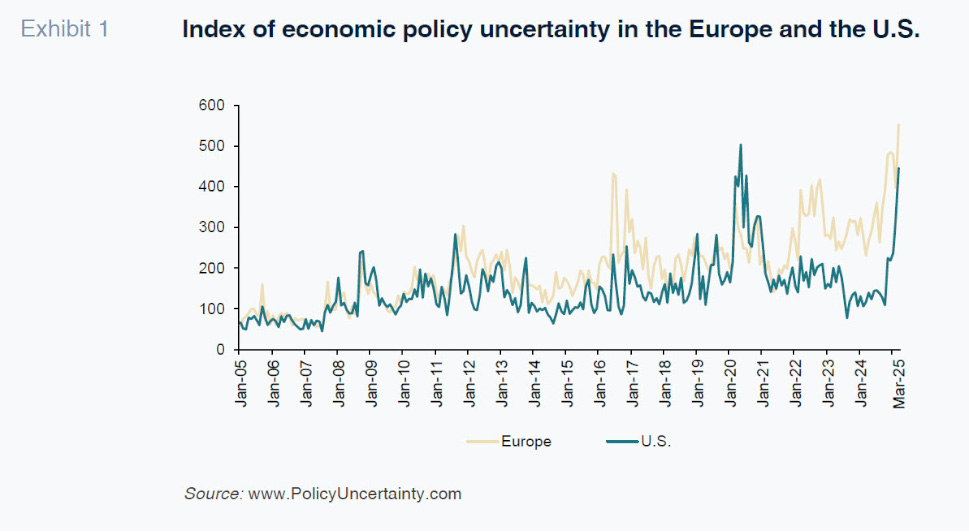

The United States’ tightening of tariffs on imported goods –particularly from China– along with a surge in unilateral actions that violate established trade agreements, has triggered a period of instability in international economic relations. In addition to a universal 10% tariff and 25% duties on specific products such as steel, aluminum, and automobiles, the U.S. administration has announced so-called reciprocal tariffs, i.e. partner-specific levies. These reciprocal tariffs remain suspended until early July, with their implementation contingent on the outcome of ongoing trade negotiations. So far, the scope of the European Union’s potential response remains unclear, aside from a few limited, sector-specific measures already in effect. As a result, economic policy uncertainty is high on both sides of the Atlantic (Exhibit 1), fueling volatility in financial markets, which continue to react to the shifting signals from Washington.

In theory, a broad-based increase in customs tariffs produces three main effects. First, exports suffer from a loss of competitiveness, as imported goods become more expensive relative to domestic products, which remain tariff-free. For example, a 10% tariff could lead to a 10% drop in exports to the U.S., assuming full pass-through to final prices (Amiti

et al., 2019) and a price elasticity of demand equal to one

[1] –consistent with patterns observed during the protectionist episode of Trump’s first term. Second, competition from China is intensifying. Facing higher tariffs on its exports to the U.S., China is attempting to offset losses by ramping up sales in Europe. Third, the broader climate of uncertainty surrounding trade rules weighs on short-term investment. In Spain, in particular, investment in capital goods is empirically linked to goods exports.

Beyond these theoretical considerations, it is essential to define the scale of tariffs the Spanish economy is likely to face in the coming years before estimating their impact. For this purpose, we adopt a relatively benign assumption: that financial markets will constrain the reach of protectionist measures, prompting negotiations and the softening of initial intentions of the U.S. government. Specifically, the projections do not anticipate the imposition of reciprocal tariffs on Europe. In the case of China, it is also assumed that the recently concluded trade agreement will remain in effect, implying a more moderate tariff stance compared to earlier announcements and granting exemptions for products essential to the functioning of the U.S. economy –conditions that could help prevent a recession.

This assumption aligns with recent developments in U.S. tariff policy, which has shown flexibility in response to both financial market risks and macroeconomic fluctuations. It is a fact that economic activity has slowed sharply, with consumer confidence undermined by rising price risks and firms facing increased production costs. Many analysts now see a heightened risk of recession, keeping financial markets on alert and pushing policymakers toward repeated course corrections, such as the suspension of reciprocal tariffs mentioned earlier.

Even under this relatively optimistic scenario of policy adaptability, the forecasts already reflect the ongoing global slowdown. In particular, a one-percentage-point deceleration in the U.S. economy is expected, consistent with the GDP contraction recorded in the first quarter and more recent estimates from the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model. This slowdown is also contributing to weaker international trade.

[2]

Domestically, the robust pace of the Spanish economy could give the impression of a temporary decoupling. However, Spanish exports to the U.S. are assumed to face a 20% loss of competitiveness, driven by the combined effect of the 10% universal tariff and an approximately 10% appreciation of the euro against the dollar.

[3] And, this is despite the fact that the forecast assumes that reciprocal tariffs will not be implemented, while also excluding the possibility of strong retaliatory measures from the European Union.

In light of China’s intensified trade push in Europe to offset lost market share in North America, import elasticity is assumed to rise from 0.8 in 2024 to 1.2 during the forecast period –the latter figure aligning with the historical average.

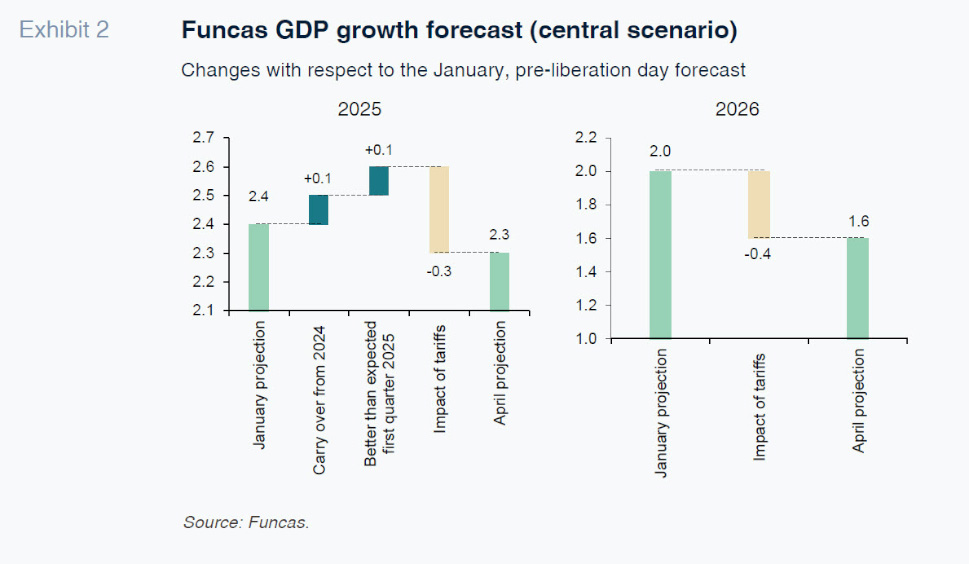

Based on these assumptions, Spain’s economy is projected to grow by 2.3% this year –0.1 percentage points below the January Funcas forecast–and by 1.6% next year, a downward revision of 0.4 points (Table 1). The upward revision of GDP by 0.2 points due to stronger-than-expected performance early in the year and a positive carryover effect from last year have been offset by the negative impact of the tariffs. Overall, the trade war is expected to shave 0.3 percentage points off growth this year and an additional 0.4 points in 2026, as a result of lower exports, stronger import competition and negative confidence effects (Exhibit 2).

Nearly half of the slowdown projected for 2026 would stem from the direct effect of tariffs on exports (0.25 percentage points),

[4] with the remainder (0.45 points) attributable to the U.S. economic slowdown and its spillover effects on international trade and confidence effects, particularly in Europe.

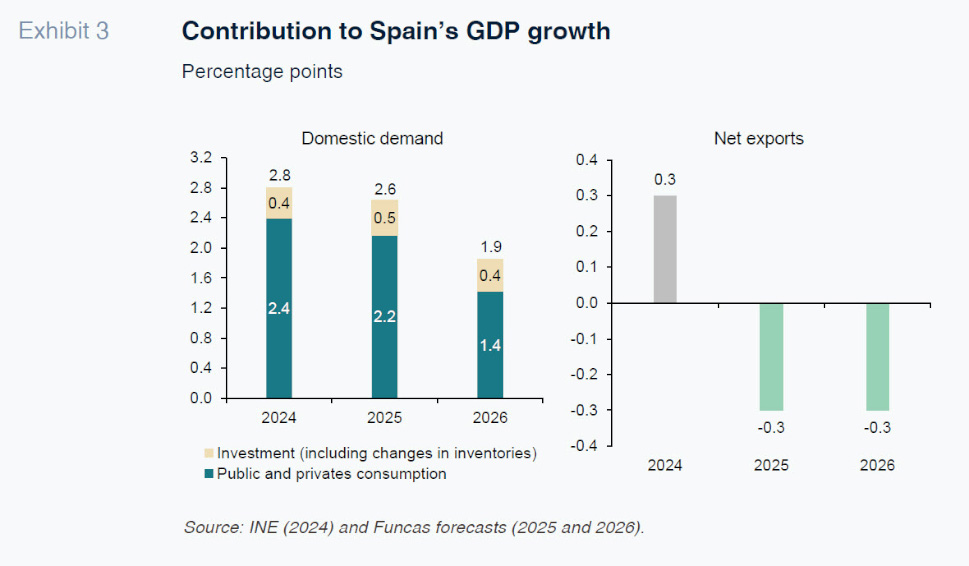

Growth will be less balanced than in previous years, driven exclusively by domestic demand, which is expected to contribute 2.6 percentage points in 2025 and 1.9 points in 2026 –unchanged and one-tenth higher, respectively, than in the January forecast. In contrast, the external sector is projected to subtract 0.3 points from growth in both years, representing a slight downward revision for 2025 and a five-tenths downgrade for 2026 relative to the previous forecast.

Within domestic demand, strong consumption growth stands out, in stark contrast to weak investment –particularly in capital goods, the segment most sensitive to the deteriorating international environment (Exhibit 3). Private consumption is set to expand at a solid pace, supported by rising household disposable income and the gradual drawdown of savings accumulated over the past two years. Public consumption is also expected to increase, though at a more moderate rate than in previous years, due to the extended budgetary framework and the system of advance payments to regional governments. This year, compensation under that system will be relatively limited, offering less fiscal leeway for regional spending compared to previous years. Residential investment is also expected to recover moderately, amid continued strong housing demand.

The rise in protectionism will negatively affect exports, particularly goods exports, which are weighed down by higher tariffs. Exports of non-tourism services are expected to lose some momentum, in line with the broader slowdown in global markets. Tourism, meanwhile, will grow more moderately than in previous years due to saturation effects observed during the summer season. Nonetheless, a new record in foreign tourist arrivals is still anticipated. On the import side, as noted earlier, import growth is expected to return to historical elasticity levels, further dampening the foreign sector’s contribution to growth.

Barring unforeseen shocks, the decline in inflation should take hold, driven by lower prices for imported goods. This reflects the appreciation of the euro, falling oil prices, and a greater influx of imports amid heightened global competition –particularly as Asian exports are redirected from the de facto closed U.S. market. The end of VAT reductions on food also had a slightly stronger impact than projected in the January forecast. Even so, the CPI is expected to rise by 2.3% in 2025 (annual average) and 1.9% in 2026, remaining broadly in line with previous estimates. In the opposite direction, potential retaliatory actions by the European Union could disrupt this disinflationary trend. For now, the scenario is still dominated by disinflationary trends, supporting the rate-cutting cycle by the ECB, with the one-year Euribor projected to fall to 2% by year-end and to 1.75% in 2026.

The labor market will continue to expand, though at a slower pace than in recent years. Net job creation is projected at 360,000 annually over 2025–2026, compared to an average of 550,000 in the previous two years. A slowdown in labor force growth is also expected, as housing shortages act as a constraint on immigration and new labor force entries more broadly. The unemployment rate is forecast to fall to 10% in 2026, five-tenths of a point below the previous estimate–partly due to the stronger-than-expected close to 2024, which was not yet available in the January forecast.

Following a historic surplus last year, the current account balance is expected to narrow over the forecast period, though remaining in positive territory. This reflects the expectation of a sharp deceleration in export volumes and a rebound in import volumes. The external surplus is projected to decline to 2.3% of GDP in 2026, down 1.2 points from the previous forecast, but still a solid level.

Public deficit projections have changed little. The budget deficit is expected to fall to 2.9% of GDP in 2025 –or 2.6% excluding the impact of Storm Dana– and to 2.8% in 2026. Given the persistence of the fiscal imbalance and the economic slowdown, public debt will likely remain close to 100% of GDP, leaving limited fiscal space to respond to any future shocks. This dynamic, combined with rising defense spending plans across Europe, is reflected in higher government bond yields compared to the January projections.

Risks of an alternative scenario of persistent uncertainty

The above forecasts –which suggest a relatively limited impact from the trade shock –rest on the assumption that the U.S. government will not fully implement its protectionist measures and that new trade rules will be established within a reasonable timeframe, bringing an end to the current period of instability. While this outcome is desirable, it is far from certain. A more adverse scenario is also conceivable: one in which uncertainty –marked by a series of announcements, counter-announcements, and policy reversals (as has recently occurred)– persists throughout the forecast horizon (2025–2026), or in which reciprocal tariffs are ultimately activated. Such developments would have a direct effect on the economy, fostering a climate of uncertainty highly detrimental to investment decisions.

Estimating the effect of prolonged uncertainty on investment is difficult. The impact is likely nonlinear, intensifying under conditions of acute stress, and there are few recent historical precedents comparable to the current situation.

[5] Nevertheless, the following paragraphs attempt to approximate the potential magnitude of this effect.

Using the investment behavior observed during the European debt crisis as a reference –particularly in countries not experiencing a banking crisis like Spain’s– and considering the concurrent impact on other variables sensitive to global uncertainty (such as Spanish exports of tourism services), along with multiplier effects on employment and consumption and a modest disinflationary impact, it is possible to estimate a GDP loss of 0.3 percentage points this year and 0.2 points next year. In this scenario, the drag on GDP from uncertainty-induced investment weakness would be concentrated in the second half of 2025. This impact would come in addition to the effects already included in the baseline forecast. The impact on construction investment, however, is expected to be negligible, as it tends to follow its own cycle and respond more slowly to changes in the broader economic environment.

Taken together, in an alternative scenario where elevated uncertainty persists long enough to weigh on investment, GDP growth would fall to 2.0% in 2025 and 1.4% in 2026, with negative quarter-on-quarter growth rates expected in the final two quarters of 2025.

The deterioration could prove even more severe if the U.S. economy were to enter a recession and inflation were to surge again, eroding household purchasing power. Such a scenario –clearly undesirable for all economies– would involve cascading effects: collapsing confidence, reduced consumption and investment, financial market turmoil, and capital flight toward perceived safer havens (the much-feared “Liz Truss moment”). While such a vicious cycle remains highly unlikely, if it were to materialize, reversing it would be extremely difficult.

Notes

The 35% tariff imposed in 2018 on Spanish olive imports generated an equivalent reduction in shipment volume, consistent with unit elasticity.

For a discussion of recent developments in the U.S. economy, see Jarrett (2025).

While some sectors, such as pharmaceuticals, are exempt for the time being, others such as steel, aluminum and automotive face a specific levy. On the other hand, the Trump administration has announced that the exemption of pharmaceutical imports for the purposes of the universal tariff is temporary.

For this estimate, see Funcas (2025).

According to the uncertainty indices, uncertainty reached maximum levels in Spain during the debt crisis of 2012 and in 2020. But these were situations of a different nature, and there were other factors in addition to uncertainty acting on investment – the paralysis of credit flows due to the financial crisis and the high indebtedness of companies in 2012 – which are not present in the current situation.

References

Raymond Torres, María Jesús Fernández and Fernando Gómez Díaz. Funcas