Outlook for Spain’s economy and public finances: 2024-2025

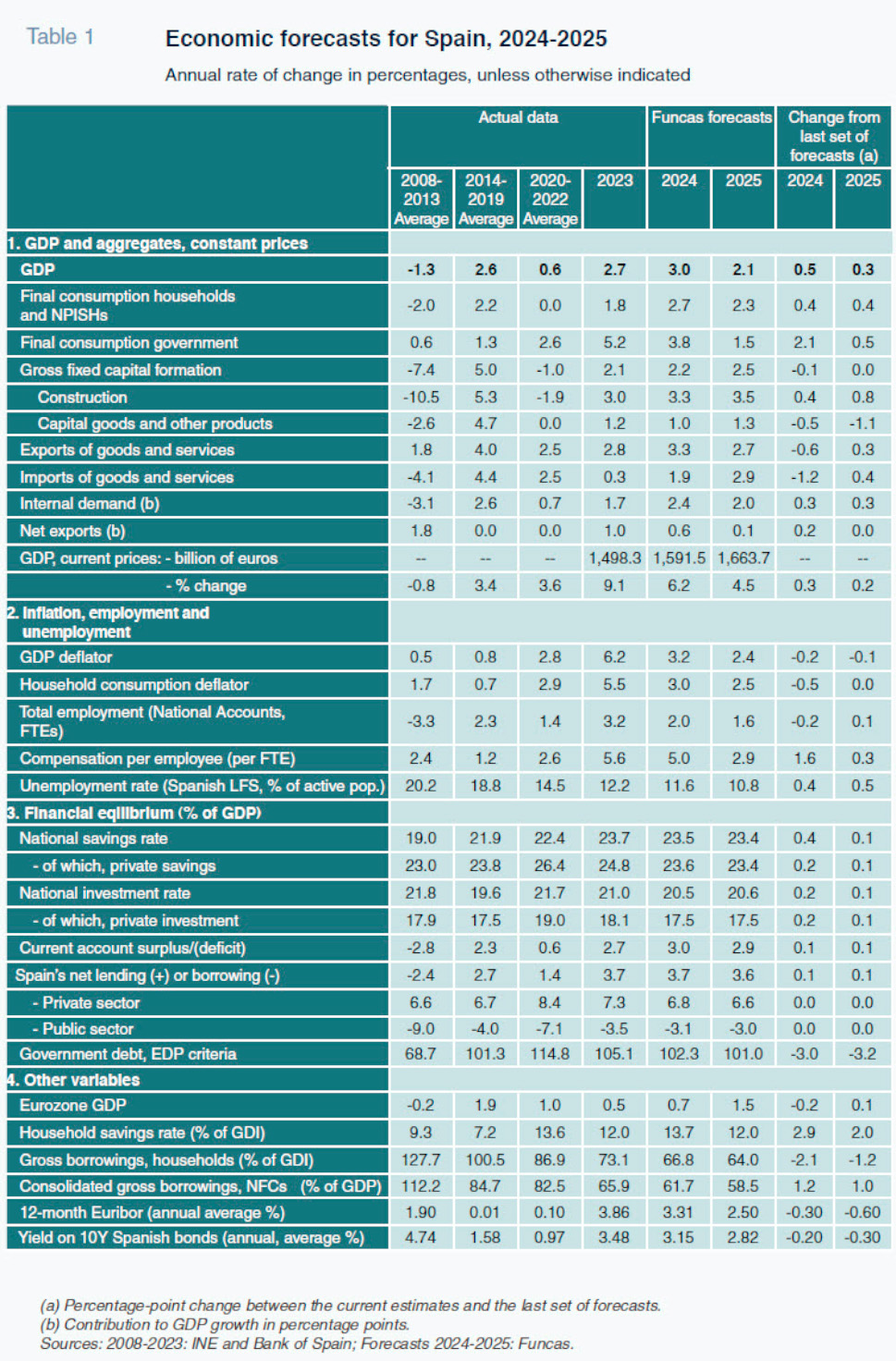

The Spanish economy continues to grow faster than the European average, with growth projections revised upwards for 2024 and 2025 to 3% and 2.1%, respectively. However, fiscal slippage relative to official targets is expected in 2025, requiring the government to introduce approximately 8 billion euros in budget savings to align with official targets – allowing for sustained short-term growth, while increasing confidence and providing space for discretionary spending in the event of future shocks.

Abstract: The Spanish economy continues to grow faster than the European average. The current growth cycle is being driven by the favourable external competitiveness position, especially in terms of both tourism and non-tourism services. Another factor is the contribution by immigration to the labour force. Public consumption has also fuelled growth, though this is hardly sustainable in light of fiscal rules. The economy is expected to grow by 3% this year and 2.1% in 2025, which is 0.5 and 0.3 percentage points up from our last set of forecasts. Despite the economic momentum, the public deficit will not fall below 3% in 2025, coming in half a point above the official target. To align with the target, the government would have to introduce budget savings in the order of 8 billion euros, an effort that would not jeopardise growth in the short-term and would generate benefits in the medium-term in terms of confidence and room for manoeuvre in the event of future shocks.

Faster than expected economic growth

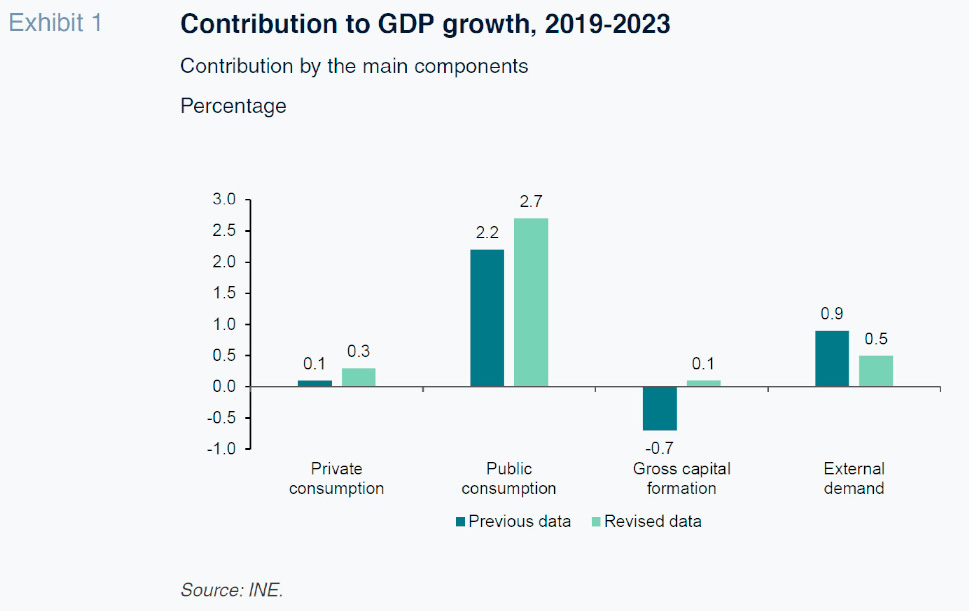

Last September, Spain’s statistics office, the INE, carried out its ordinary and extraordinary review of the entire series of national accounting figures. The result was to increase the level of cumulative GDP growth in the post-pandemic period, from 2.5% to 3.6%. Domestic demand contributed 3.1 percentage points to the revised figure, with foreign demand adding the remaining 0.5 percentage points. Within domestic demand, the INE revised the contributions by the various components higher. Nevertheless, the contribution by public consumption remains very significant (2.7 points), with private consumption much weaker. Most notably, however, the contribution by gross fixed capital formation remains negative (i.e., this component is still below its 2019 equivalent), although the contribution by total gross capital formation (including inventories) was close to neutral. As for the foreign sector, its contribution has been revised downwards. However, the contribution by net exports of non-tourist services remains surprisingly strong, at 1.4 percentage points, which is more than the contribution by tourism, with the net trade in goods detracting from growth (Exhibit 1).

Turning to this year, GDP growth has been remarkable for the first three quarters, particularly by comparison with the eurozone average: the Spanish economy registered growth of 0.9% in the first quarter and of 0.8% in each of the following two quarters. The year-on-year rate of growth in the first nine months of the year was therefore 3%. Private consumption increased by 2.6%, fuelled by the recovery in purchasing power and growth in employment, despite which, in real per capita terms, this metric remains below 2019 levels. The most eye-catching growth, of 4.6%, came in public consumption.

As for gross fixed capital formation, the construction component registered growth of 2.5% in the first nine months of the year, with capital goods notching up growth of 1.5%. The weakness in the latter aggregate remains a concern: by the end of September 2024 it had yet to recover from the contraction sustained in 2020, and throughout the entire post-pandemic period, its growth has been lagging behind GDP, which is very unusual during periods of economic growth.

The foreign sector contributed 0.6 percentage points to GDP growth in the first nine months, led by the growth in tourist services, of 12.6%, and non-tourist services, of 9.3%, while overseas sales of goods contracted somewhat. Growth in imports has been trending below the historical elasticities relative to end demand, which may be attributable, albeit only partially, to the composition of Spanish growth, marked by lower contributions by the more import-intensive components: GFCF and goods exports.

So far this year, GDP growth has been much stronger than expected at the start of the year. In January of this year, the consensus forecast tracked by Funcas called for growth of 1.6% in 2024. The outperformance is attributable to sharp and unanticipated growth in public expenditure and in exports of tourist services.

Role of immigration

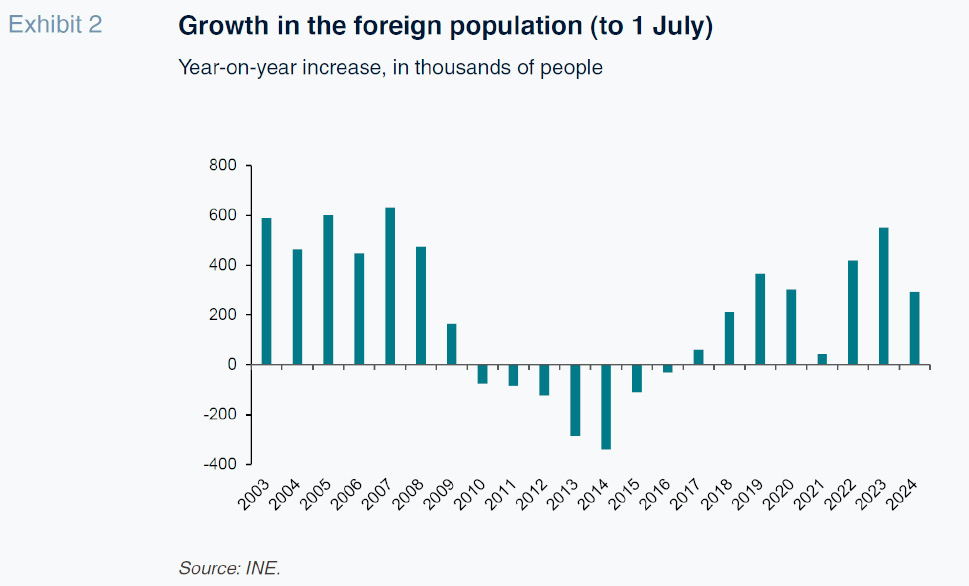

A key factor underpinning Spain’s economic growth in recent years has been the growth in the foreign labour force. The immigrant population increased by 1,263,000 between July 2021 and July 2024, while the national population increased by only 187,000 during thesame period. Albeit a high figure, it is in the vicinity of the numbers observed prior to the crisis of 2008 (Exhibit 2).

As a result, the active foreign population increased by 737,000 in the third quarter of 2024 compared to the same period of 2021. The number of foreign job holders increased by 810,000, which means that, on aggregate, the entire new active immigrant population found work, along with some of those that were formerly unemployed. Moreover, those 810,000 jobs account for 47% of total employment created during the period, underlining the importance of foreign labour to economic growth in recent years.

The foreign population’s contribution to the economy materialises not only on the supply side, by providing the human resources needed to cover vacancies in numerous sectors that are finding it hard to attract workers, but also on the demand side, by boosting private consumption. According to the Household Budget Survey, 25% of the increase in total private consumption between 2021 and 2023 originated in households whose main provider was a foreigner. Nevertheless, private consumption contributed a mere third of GDP growth during the period, which means that the main contribution by the foreign population came on the supply side.

Economic forecasts, 2024-2025

Funcas projections assume a shift to less expansionary fiscal policy than in recent years, accompanied by less contractionary monetary policy. The change in the macroeconomic mix, similar to that anticipated in earlier sets of forecasts, is shaped, firstly, by budget targets, taking into account the reactivation of the European fiscal rules and the need to place massive amounts of debt on the markets on terms that the public treasury can afford, something that is only possible with a fiscal roadmap that inspires confidence. Secondly, the change in the policy mix which is hypothesised in the present projections reflects the expectation that the ECB will adjust its interest rates as disinflation takes hold across the eurozone. We are assuming that the deposit facility rate will trend down to around 2.5% by the end of the projection period.

As for the international climate, the assumption is that the Middle East conflict will continue to undermine confidence, but without seriously destabilising trade in this fossile-rich region, or at the global level. We are forecasting Brent oil prices of around $75 per barrel throughout the projection period. Elsewhere, disinflation in Europe should create space for a slight uptick in consumption and growth over the course of next year.

Framed by these assumptions, and factoring in the growth reported in the first half of the year, we are projecting GDP growth of 3% in 2024, up half a percentage point from our last forecasts. This upward revision is mainly shaped by a bigger contribution by domestic demand, particularly public consumption, which would expand faster than expected. We have also raised our forecasts for private consumption in response to higher than anticipated growth in pay: as in other European markets, wage negotiations are featuring mechanisms articulated to compensate for the loss of purchasing power in recent times. On the other hand, we still expect gross fixed capital formation to remain relatively weak, leaving our forecasts for this key variable largely unchanged. Lastly, the external demand contribution is now expected to be stronger than initially anticipated: the growth in exports, while less dynamic than originally contemplated, is more than offsets by a weak import elasticity.

Altogether, the main drivers of growth in 2024 will be public consumption and net exports, with both registering growth of over 3%. The boom in exports is noteworthy in the current context of lethargic European markets, coupled with rising trade barriers between major trading blocs. The momentum in tourism (with forecast growth of 13.4% in real terms in 2024) and non-tourist exports (+9.7%) is eye-catching and more than offsets the small contraction in goods’ exports (-0.4%). Elsewhere, for the second year in a row, growth in imports will continue to trail demand. This abnormally-low import elasticity is partly attributable to sluggish investment in capital goods, a variable characterised by a high import intensity.

Demand in the private sector is also expected to lag GDP growth. We are projecting growth of 2.7% in private consumption, two points below the rise in disposable household income in real terms. The gap between income and spending will lead to a significant increase in the savings rate, a trend which can be ascribed to market uncertainty and high interest rates, encouraging households to deleverage and take a cautious approach to spending. As noted, we are forecasting limited growth in gross fixed capital formation, particularly in terms of investment in capital goods. The non-financial corporation sector is expected to continue to present a net lending position (difference between disposable income and investment) equivalent to 1.5% of GDP.

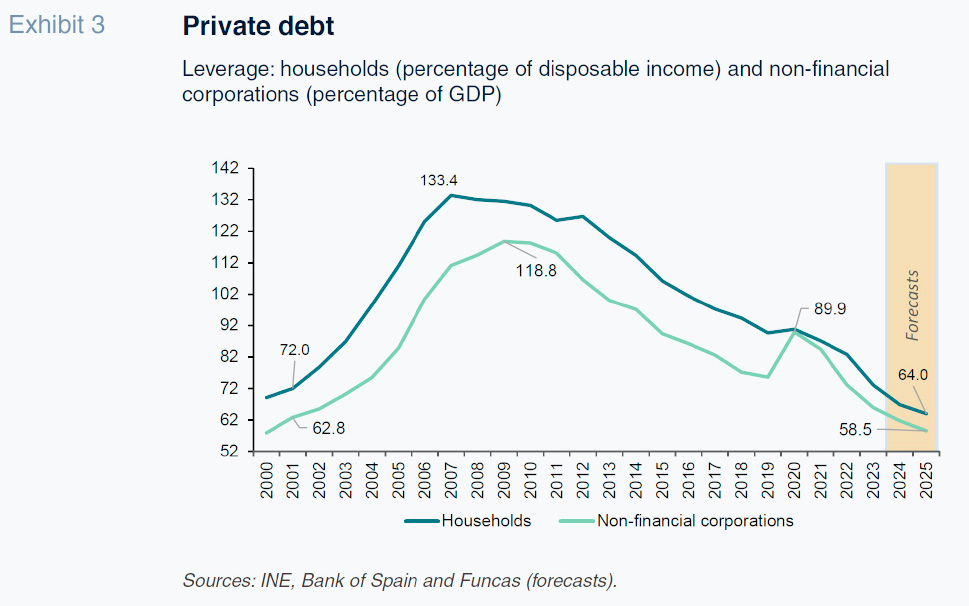

In 2025, we are projecting GDP growth of 2.1%, down from this year as already anticipated in our earlier estimates. That growth is expected to come almost entirely from domestic demand, which should account for 2 points. We are forecasting strong growth in private consumption, underpinned by job creation and the release of some of the excess savings. Investment should pick up slightly as the deadline for executing the Next Generation funds gets closer, with lower interest rates stimulating the demand for credit. As a result, we expect the private sector to continue to deleverage: liabilities are expected to reach lows for the century for both household and non-financial corporations (Exhibit 3). On the other hand, we are forecasting a slowdown in public consumption, as the European fiscal rules start to bite, and in light of intensified market vigilance.

The external sector is expected to contribute just 0.1 points to GDP growth in 2025 as the growth in tourism eases and imports revisit their historical elasticities.

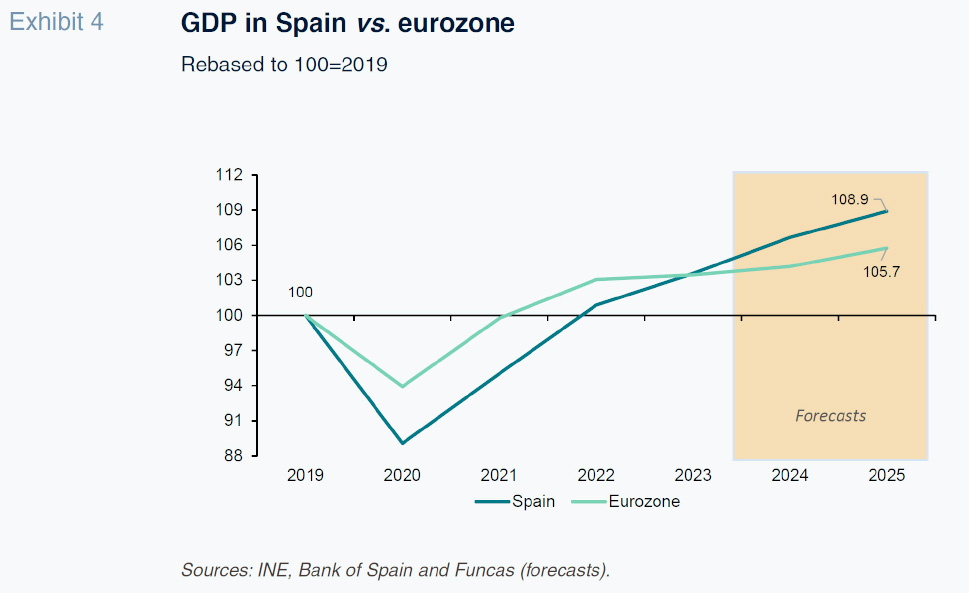

In short, over the next two years we are forecasting more vigorous growth than initially expected, thanks to fiscal expansion and the Spanish economy’s favourable competitive positioning, particularly in both tourism and non-tourism services. These projections contrast with the meagre growth forecast for the eurozone: by year-end 2025, Spanish GDP is expected to be 8.9% above pre-pandemic levels, compared to a European average of 5.7% (Exhibit 4).

Disinflation should take hold in the coming quarters, as food prices ease and energy costs hold relatively stable. However, core inflation, particularly as regards services, is expected to prove more stubborn. As a result, while headline inflation should dip just below 2% in 2025, the GDP deflator, which reflects the underlying price pressures, is projected to remain at 2.4%. We are expecting a small impact in 2025 from wage adjustments designed to offset the loss of purchasing power, thereby curbing the growth in average earnings per employee. Real wages would therefore increase by a mere 0.4%, broadly in line with productivity.

Between the second quarter of this year (latest figures available) and the end of 2025, we are forecasting net new job creation of close to 550,000 in Labour Force Survey terms. While still a significant increase, job creation would in fact be slower than in recent times (between the end of 2021 and the second quarter of this year, Spain created net new jobs of over one million). The strong job performance should drive the unemployment rate down towards 10.5% by the end of next year, which is slightly above our last forecast due to the incorporation of new immigrants into the labour market. The unemployment rate would still remain well above the European Union average.

Thanks to strong export performance, the current account surplus is projected at 2.9% of GDP in 2025, which is about the same as we are forecasting for this year. The overall surplus masks two contrasting trends: a significant surplus in the balance of trade in goods and services, more than offsetting the deficit in income generated by the growing impact of remittances by immigrants. At any rate, the foreign surplus is expected to remain virtually unchanged in 2025, facilitating a significant reduction in external debt.

Fiscal projections

Despite such strong economic growth, little progress has been made on reining in the country’s budget imbalances so far this year. The deficit built up in the first eight months of the year at all levels of government (excluding local government) stood at 2.3% of GDP, up 0.1 of a percentage point year-on-year. That performance is the result of higher growth in expenditure than expected in light of the budget carry-over: all signs suggest that the dampening effect on expenditure of that rollover has been neutralised by changes in the credit and settlements on account provided to the regional governments.

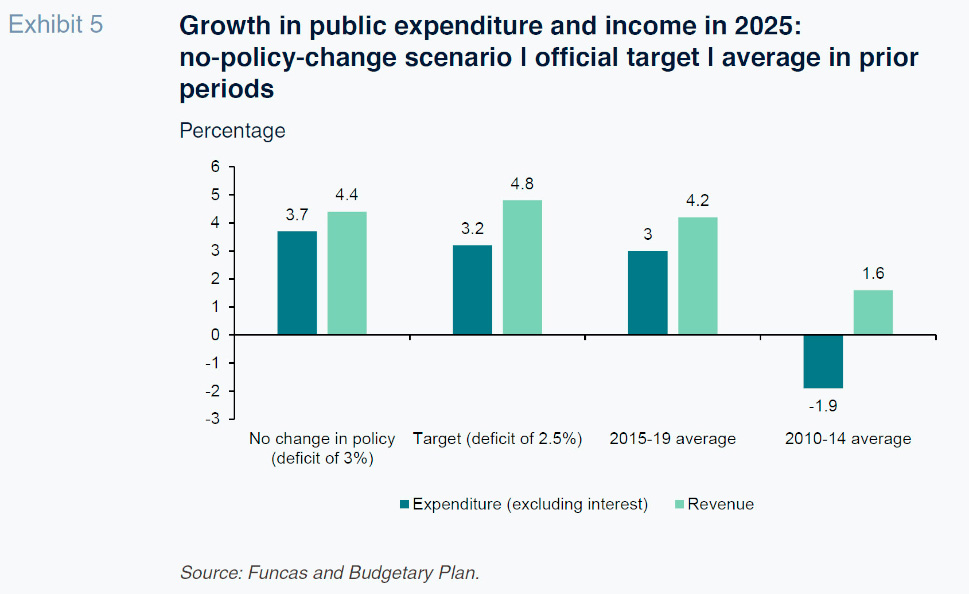

The current forecasts suggest that the hole in the budget will remain larger than would be expected at this juncture of the cycle. That is because momentum in expenditure by the authorities is offsetting the extra tax being collected as a result of the vigorous economic growth. As a result, we are projecting a deficit of 3.1% of GDP this year and 3% in 2025 – which is half a point above the government’s official target. The slippage reflects the fact that these forecasts are based on policies either approved or announced, while the official target factors in new measures the details of which are unknown at the time of writing. To reduce the deficit by half a point, the government would need to pare it down by almost 8 billion euros, an adjustment that is similar in size to that made between 2015 and 2019 (Exhibit 5). Such a budget saving would be relatively small, thus having a limited impact on growth in the short-term, and yet generating benefits in the medium-term in terms of confidence and room for manoeuvre in the event of future shocks.

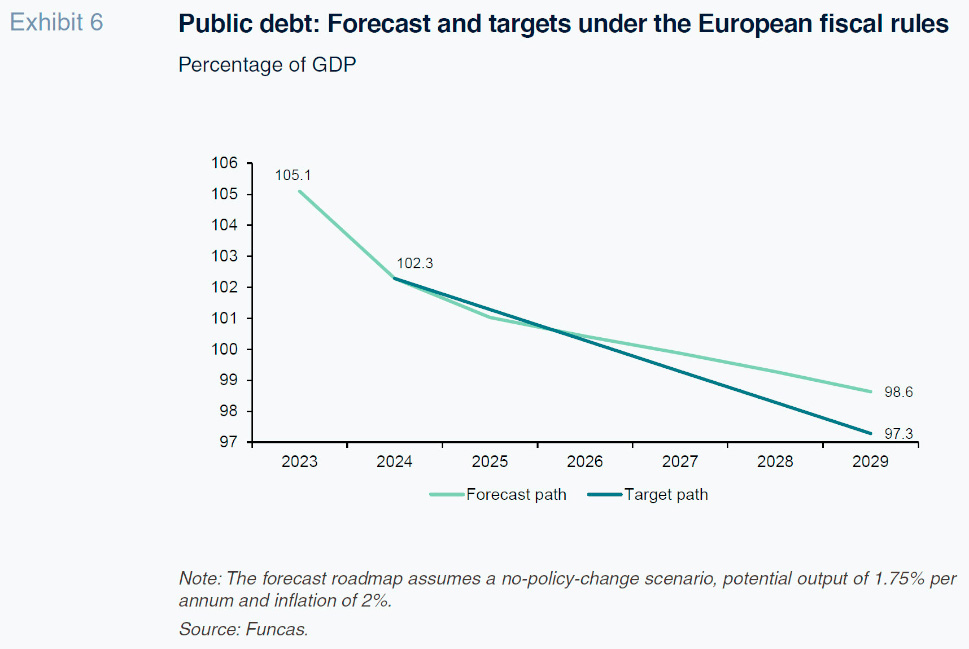

Assuming a scenario of policy continuity and absent detailed information about the planned adjustments, Spain’s public debt will continue to come down in the coming years but at a slower pace than is required to comply with the European fiscal rules (Exhibit 6). Besides its commitments to the European Union, the persistence of a sizeable fiscal deficit implies scant room to respond to swings in the economic and financial environment. To steer clear of those risks, the deficit needs to be cut further and trendline economic growth needs to be higher, a scenario that requires a recovery in investment and productivity.

Risks

The main risk to delivery of these forecasts continues to lie with geopolitical strains and global trade fragmentation. Other risks relate to some of Spain’s most important European trading partners: the German economy could take longer than expected to rebound, while the markets are watching the fiscal situation in France closely. In this scenario, the persistence of a high deficit poses a risk to fiscal sustainability and minimises space for economic policy manoeuvring in the event of shocks.

As for the upside, the household savings rate could come down faster than expected, giving household consumption a boost. Note, moreover, that both the household and corporate sectors are in much better financial health on aggregate terms.

Longer-term, the stagnation in corporate investment is a concern. A chronic shortfall of investment would compromise the prospects for a recovery in productivity, the Achilles heel of the Spanish economy. Finally, the weakness in residential investment, were it to persist, could constrain labour mobility, the inflow of foreign workers and potential output.

Raymond Torres, María Jesús Fernández and Fernando Gómez Díaz. Funcas