The outlook for the deficit: The calm before the storm

It will require a concerted effort to bring down Spain’s deficit and debt levels, involving higher annual reductions than those prior to the pandemic. However, it is not just the central government which needs to address this issue, with many regional governments facing financial challenges ahead.

Abstract: Although Spain’s deficit came in lower than expected in 2020, it still ranked highest among the EU-27. While the government’s budget deficit forecast of 8.4% for 2021 is very similar to the Funcas consensus forecast of 8.2%, Spain faces a structural deficit in 2022 even higher than the 3.5% observed in 2019. This suggests the return to budget stability will be tough and requires a credible strategy for tackling the debt and deficit challenges to be defined in 2021. Such a strategy will need to cover until at least 2027 and will necessitate higher annual reductions than were being required of the country under the European fiscal rules before the pandemic (-0.65%). In the case of the regional authorities, the situation is more urgent as some of the income transferred in 2020 and 2021 to them by the central government will have to be returned in 2022 and 2023. Also, some regions will face significant financial stress and the reform of the regional financing regime needed to fix the problem remains bogged down. Lastly, the gradual ageing of the Spanish population will exert upward pressure on spending in health and social services, which between them account for over half of the regional budgets.

Introduction [1]

At 10.1%, Spain’s public deficit came in lower than most analysts and the government expected in 2020 (Lago-Peñas, 2021; Ministry of Finance, 2021a). The main reason for this is the significantly smaller than forecast drop in non-financial income. Although GDP contracted by 9.9% (by 10.8% in constant prices according to Spain’s National Statistics Offi public revenue at all levels of government decreased by just half as much (-5%).

Nevertheless, according to Eurostat, Spain reported the highest deficit and sustained the biggest GDP contraction in the European Union (EU-27) in 2020. The economic impact of the pandemic has been relatively greater than the impact on the country’s health indicators. That is mainly because of the relative weight of the sectors most affected by the restrictions on mobility and social distancing (tourism and hospitality). According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), as of December 31st, 2020, Spain ranked ninth in the EU-27 by number of confirmed cases per million inhabitants.

A sharper correction in GDP in 2020 translates into brighter prospects for recovery in 2021, particularly during the second half of the year when many of the restrictions are removed and vaccination takes off Nevertheless, the pandemic continues to take a toll on public revenue and spending. Spain’s recent history of high public deficits and the size of the economic shock make it particularly important to map out a fiscal consolidation roadmap today for implementation starting from 2022, even before the fiscal rules are reinstated and the European Central Bank’s extraordinary debt purchase programme is rolled back. Both factors are making it possible to finance enormous volumes of public debt at a historically low cost. While Spain benefits from calmer market today, the future could become more turbulent if the country fails to implement the necessary reforms.

Against that backdrop, the purpose of this paper is three-fold. First, we will examine the outlook for Spain’s public deficit in 2021. Second, we will present scenarios for the medium-term and discuss the necessity of reining in the budget. Third, we conduct a regional analysis, which shows a more acute fiscal situation.

Outlook for Spain’s public deficit in 2021

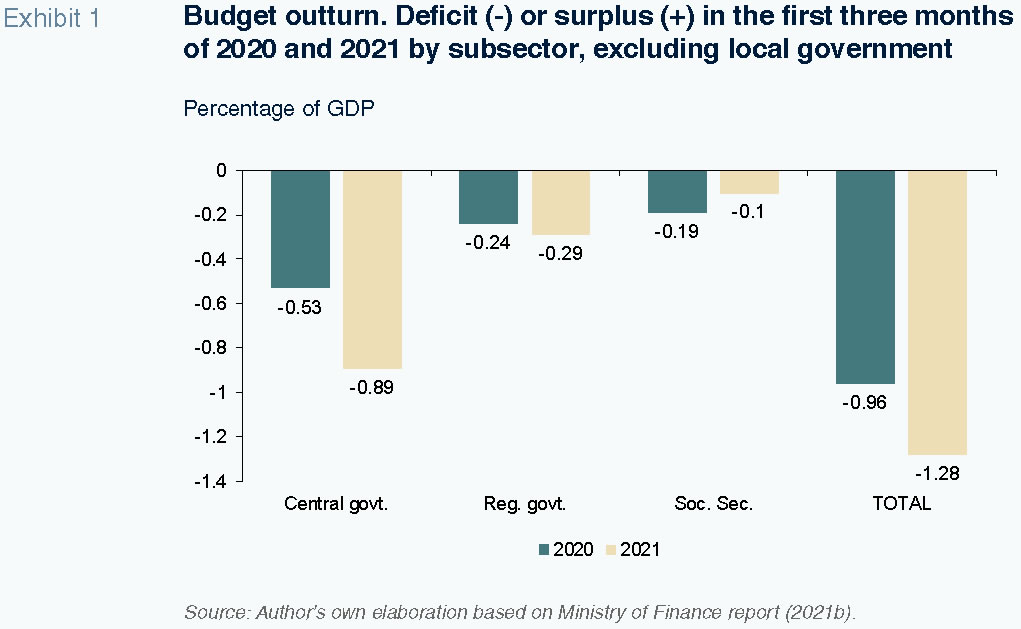

Exhibit 1 shows the preliminary budget numbers for the first quarters of 2020 and 2021. The figures are expressed as a percentage of Spanish GDP. The pandemic is not yet refl in the first-quarter 2020 figures. That is why those numbers are relatively better (-0.96 vs. -1.28), particularly in respect of the central government (-0.53% vs. -0.89), which has taken on the main financial burden, transferring money to the sub-central levels.

Unlike in an ordinary year, the predictive value of these preliminary budget reports is extremely limited. By way of alternative, the real-time analysis conducted by Spain’s independent fiscal authority, AIReF, points to a deficit of 7.8%, albeit framed by a still-wide confidence interval of 6 to 9 percent as of June (AIReF, 2021a).

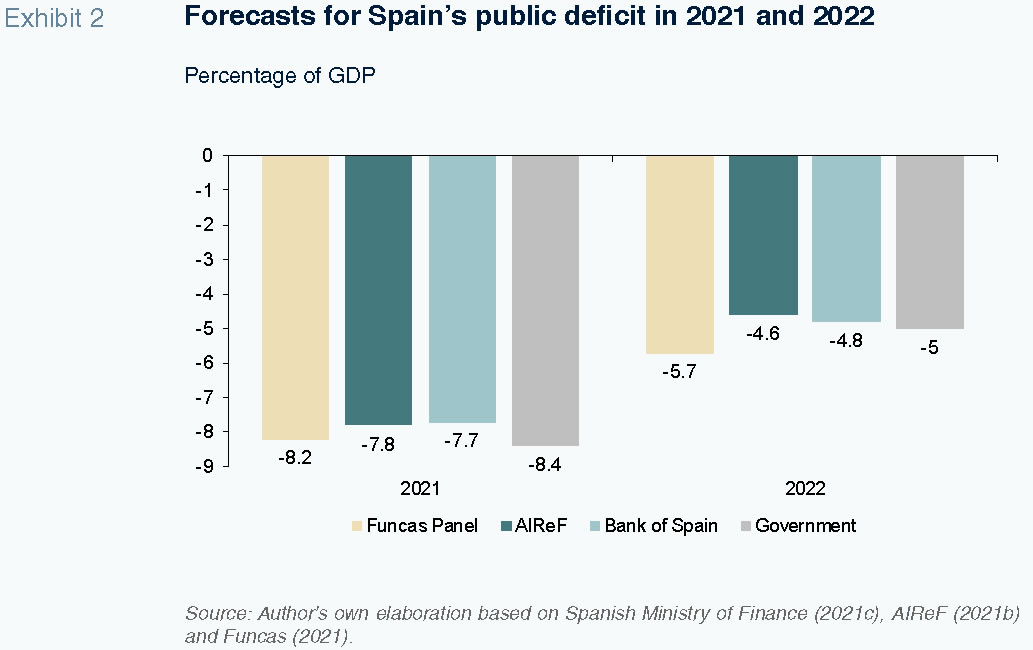

Exhibit 2 juxtaposes the forecasts of AIReF, the Bank of Spain, Funcas (consensus) and the government. The estimates hover around 8% and suggest that the government’s forecast of 8.4% is fairly reasonable. Incidentally, this forecast is slightly more pessimistic than the Funcas consensus forecast of 8.2%.

The projected improvement in the deficit is notably slim. It entails a correction of around 1.7 percentage points. By comparison, the Ministry of Finance (2021c) has forecast a very substantial reduction in the negative output gap in 2020 from -10.4% in 2020 to -5.3% this year. As the output gap is expected to be virtually nil in 2022 (-0.3%), the figures presented on the right side of the exhibit are eye-catching. By 2022, the cyclical deficit should be negligible yet the government is forecasting a deficit of 5% compared to the Funcas consensus forecast of 5.7%. Part of the deficit could still be attributable to discretionary income and expense support measures for tackling the pandemic. However, these measures should be significantly pared back by then. This would suggest a structural deficit in 2022 higher even than the 3.5% observed in 2019. The return to budget stability in 2023 and beyond is going to be very tough.

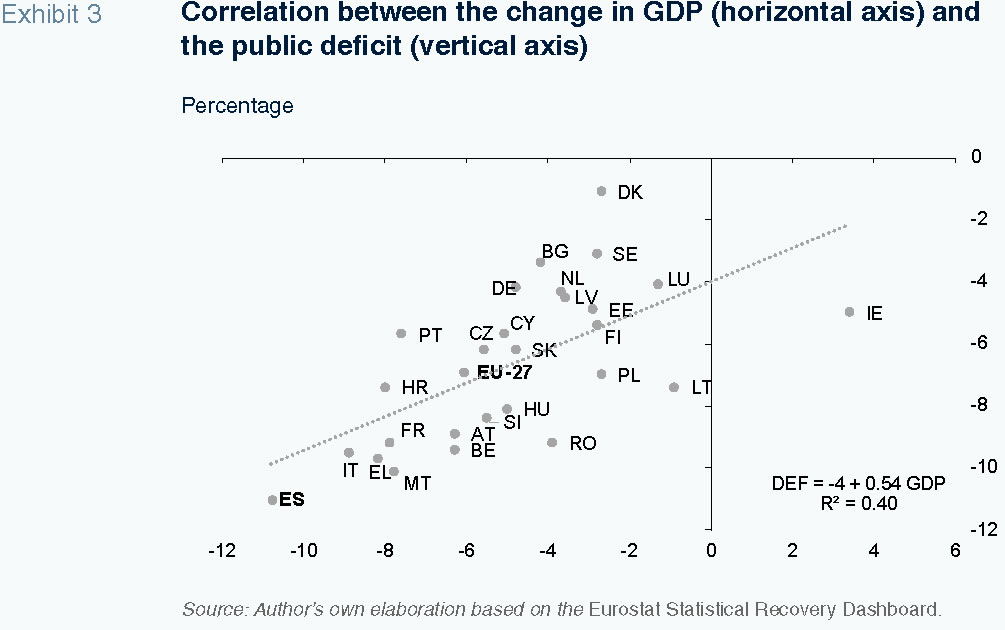

Exhibit 3 depicts the correlation between the observed deficit as a percentage of GDP and the contraction in GDP in 2020 across the universe of EU-27 countries. The relationship between the two variables is direct and statistically significant.

[2] The slope of the regression line suggests that, on average, for every additional point of GDP correction, a nation’s deficit deteriorated by 0.54%. However, the R

2 (0.40) indicates the existence of differences between countries, related mainly with the differences in fiscal responses to the pandemic and in the structural deficit. Spain is the outlier, registering the biggest contraction in GDP and the highest deficit. Its deficit is 1.1 percentage points higher than that predicted by the regression line. The explanation for that deviation lies with the structural component of the deficit rather than a particularly intense discretionary fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis. According to the IMF’s most recent calculations (April 2021), Spain lies at the median in the ranking of EU-27 member states for the size of budgetary fiscal support measures rolled out at the national level in response to the pandemic.

[3]

On the 2021-2024 stability programme and beyond

There is broad consensus in the analyst community about the need to wait until the pandemic is behind us and the economy is recovering before starting to implement budget consolidation measures. There is also agreement, however, that it is important to define an effective and credible strategy for tackling the challenges on the public deficit and debt fronts in 2021. Through that prism, the assessment of the 2021-2024 Stability Programme Update is disappointing.

Sanz and Romero (2021) view the deficit- cutting roadmap as optimistic and question the existence of a genuine budget consolidation plan. AIReF, meanwhile talks of the need to round out the fi strategy for the medium-term, crafted around the 2021 Programme, by expanding its time horizon and specifying concrete lines of initiative (AIReF, 2021b). The comparison between Spain and Germany is telling. Germany has already extended the horizon of its medium- term budget strategy to 2025 and has a detailed and specifi national plan for the entire period. Lastly, AIReF is forecasting a defi in 2024, assuming no additional measures, of 3.5% and a stock of public debt equivalent to around 115% of GDP.

In short, Spain headed into the pandemic with a hefty legacy deficit, repeated fiscal target misses since early last decade and the deferral of several reforms that are necessary to ensure the sustainability of Spain’s public finances (tax system, regional financing, pensions, systematic appraisal of the social return of spending programmes). The pandemic arrived in the context of budget imbalance and outstanding reforms.

The situation requires action now, with the design of a new strategy based on three pillars. First, it is necessary to extend the time horizon of the budget plan. If Germany, with debt-to- GDP of 70% and a deficit of 4.2% in 2020, has adopted a strategy that runs to 2025, Spain’s programme needs to cover until at least 2027, as is the case in France.

Second, broad political consensus needs to be reached about the structural deficit roadmap for 2022-2027. Assuming that the target is to eliminate the structural deficit, it would be reasonable to spread the reduction out evenly in time so that the sacrifices are borne across different terms of office and governments. According to the calculations made by the Ministry of Finance (2021c), as set down in the Stability Programme, the structural deficit in 2024, without policy changes, would be 4.2%, a figure AIReF estimates at 4.6%. Elimination of the structural deficit between 2022 and 2027 would certainly require higher annual reductions than were being required of the country under the European fiscal rules before the onset of the pandemic (-0.65%).

It is true, however, that the structural deficit is not a directly observable variable but rather requires a degree of estimation. It is also sensitive to shocks and sudden changes in economic conditions. It makes sense, therefore, to take a more sophisticated approach, layering in the spending rule and medium-term debt targets in determining the rate and intensity of consolidation. Although the fiscal rules currently suspended are set to be reformed before their reinstatement in 2023, it is likely that the new framework will not stray far from the previous parameters. As a result, a pact for the gradual elimination of the structural deficit is bound to be aligned with whatever stability targets end up being set for the coming years. It is also important to stress that the agreed deficit-cutting roadmap be compatible with multiple combinations of ratios of spending and tax revenue over GDP. This is a political decision that should be left in the hands of the government in office as the delivery of deficit-cutting targets can be achieved using very different fiscal recipes.

Third, these actions rely on the support and proven expertise of AIReF and the Bank of Spain, a member of the Eurosystem. Both institutions bring the credibility needed to get past the scrutiny of the opposition parties, citizens, the European Commission’s supervisory bodies and the international financial markets.

Outlook through the regional prism

In the case of the regional authorities, the situation is more urgent. The central government has opted to isolate them from the financial effects of the pandemic, with an unprecedented amount of fiscal transfers (Lago-Peñas, 2021; OECD, 2021). The regional governments’ deficit in 2020 was equivalent to 0.2% of Spanish GDP. In 2021, the regional authorities’ budgets are bigger than ever, thanks to the extraordinary transfers and advent of the Next Generation EU funds.

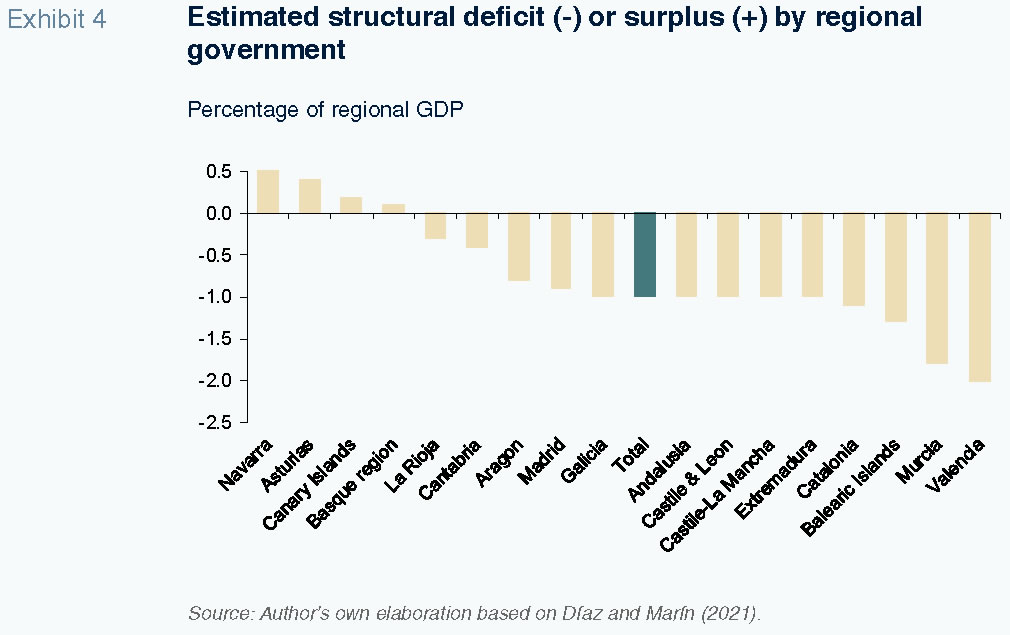

However, that situation is not as positive as it first seems. For instance, some of the income transferred in 2020 and 2021 will have to be returned in 2022 and 2023 when the corresponding financing system settlement calculations are made. First, Díaz and Marín (2021) estimate that in 2020 alone, that eff will lift the deficit by between 0.2% and 1.5%. The differences will have to be paid in 2022. Second, there will also be a step effect in non-financial income in 2022 similar to that observed in 2010 and 2011. However, it will be smaller in scale as the recovery in GDP will be far swifter and tax revenue has not collapsed to the same degree. Third, some regions have been facing particularly intense financial revenue problems and the reform of the regional financing regime needed to fix the problem remains bogged down. Fourth, there is a risk that some of the extraordinary and non-recurring funds provided in 2020 and 2021 could be used to finance recurring budget headings. Again, Díaz and Marín (2021) estimate that 60% of the extraordinary expenditure induced by COVID-19 could become structural. It is hard to believe the figure will ultimately be that high but it is a factor worth monitoring. Fifth, the regional governments are responsible for part of the structural deficit and, therefore, should have to shoulder some of the looming budget consolidation effort. Exhibit 4 provides recent estimates for the structural deficits/surpluses (as a percentage of regional GDP) at the regional government level. The differences from one region to the next stand out, with surpluses of 0.6% in Navarre and 0.4% in Asturias, compared to deficits of 2.0% in Valencia and 1.8% in Murcia.

A sixth factor should also be taken into account that relates to the nature of the public services provided by the regional governments, particularly health and social services, including dependency care, and the outlook for those services in the medium- and long- term. The gradual ageing of the Spanish population will exert upward pressure on spending in both areas, which between them account for over half of the regional budgets. According to the projections compiled by Borras (2021) to 2030, demographic trends, the higher cost of new health technologies, the full implementation of Spain’s dependency care act and moderate increases in education expenditure per capita will make it very hard to comply with the “expenditure rule”, particularly in the regions facing relatively more intense population ageing (Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Madrid, Catalonia and Valencia).

There is time to avoid this gloomy prospect by taking certain decisions and making progress on outstanding reforms. In particular:

- It is possible to extend the timeframe for reimbursing the central government for the advance payments made in 2020 and 2021, as was done for the settlements due in respect of 2008 and 2009. Bear in mind that the expected size of the settlements payable will be sufficiently smaller this time.

- Reform of the regional financing regime to reinforce tax revenue autonomy and tighten budget constraints at the regional level is a pressing matter. Engagement between citizens and politicians is the route to negotiating a compatible package of taxes, services and benefits. Until those reforms are negotiated and implemented, it would be reasonable to adopt certain temporary measures to improve financing for the regions with lower financing per inhabitant and to make the personal income tax withholding system more fl so that the decisions taken by the regional governments quickly impact tax receipts and taxpayers’ withholdings.

- Much remains to be done to assess the quality of public spending, particularly in the health arena, given its weight in the budget and the upward pressure on spending, partly due to the advent of new technology. Proposals such as that of Hispanice [4] mark the way forward.

- Fiscal governance needs to be improved at all levels. For that to happen, assuming no changes in the pro-constitution majority, the institutions already in place need to be reinforced. Specifically, the Fiscal and Financial Policy Council, CPFF for its acronym in Spanish, should be beefed up and its internal regime revisited to give the regional governments greater voting power. The regional government heads should meet formally more often to support the work of the CPFF. The inter-governmental bodies that meet to address specific topics should be revitalised as a governance tool, guided by the CPFF when they gather to tackle matters with a financial impact.

- Lastly, it is time to revise the sub-central fiscal rules as part of the process of reviewing those rules at the European level (Martínez, 2020).

Notes

The author would like to thank Diego Martínez López (UPO) for his valuable input and Alejandro Domínguez (GEN-UVigo) for his assistance.

Aside from the probable simultaneous effect of one variable on the other, insofar as the tax cuts or higher spending (= more deficit) may have had some impact on the size of the GDP contraction via effective demand.

References

AIReF (2021a). Monthly stability target monitoring. A. General Government. June 4

th, 2021. Retrievable from:

www.airef.esAIReF (2021b).

Report on the 2021-2024 Stability Programme Update. Retrievable from:

www. airef.esBORRAZ, S. (Coord.) (2021).

La sostenibilidad del gasto social en las haciendas autonómicas [Sustainability of regional government social spending]. Madrid: Funcas. Retrievable from:

www.funcas.esDÍAZ, M. and MARÍN, C. (2021). El saldo estructural de las CCAA. 2018-2020 [Structural deficit/ surplus by region].

Estudios sobre la Economía Española, 2021/17. Retrievable from:

www.fedea.esFUNCAS (2021).

Spanish Economic Forecasts Panel. July 2021. Retrievable from:

www.funcas.esLAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2021). Subcentral finances: Year two of the pandemic.

SEFO, 10(2). Retrievable from:

http://www.sefofuncas.com/Spain-in-year-two-of-the-pandemic/Sub-central-finances-Year-two-of-the-pandemicMARTÍNEZ, D. (2020). La gobernanza fiscal de las Comunidades Autónomas. Una valoración crítica de su estado actual con perspectivas de reforma [Fiscal governance at the regional level. A critical assessment of the current situation with a view to reform].

Investigaciones Regionales / Journal of Regional Research, 47.

MINISTRY OF FRANCE (2021a).

Ejecución presupuestaria de las Administraciones Públicas en 2020 [Government budget outturn report for 2020]. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esMINISTRY OF FRANCE (2021b).

Ejecución presupuestaria de las Administraciones Públicas [Budget outturn figures] Abril 2021. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esMINISTRY OF FRANCE (2021c).

Stability Programme Update, 2021 – 2024. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esOECD (2021).

The Territorial Impact of COVID-19: Managing the Crisis and Recovery across Levels of Government. May 10

th, 2021. Retrievable from:

www.oecd.orgSANZ, J. F. and ROMERO, D. (2021). Spain’s 2021 budget: An assessment.

SEFO, 10(1). Retrievable from:

http://www.sefofuncas.com/The-fiscal-implications-of-COVID-19-in- Europe-and-in-Spain/Spain%E2%80%99s- 2021-budget-An-assessment

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics Research Network (GEN), Vigo University