Progress on fiscal consolidation:

Risk of non-compliance and complacency

The dichotomy of strong economic performance and political gridlock in Spain has resulted in fiscal consolidation in line with established targets, but below initial expectations as regards timing and ambition. Fiscal slippage over the years has led to an onerous debt to GDP burden that can only be reduced over the longer term through a stronger structural fiscal effort not only on the revenue, but also on the expenditure side.

Abstract: A favourable economic context has helped Spain meet EU fiscal objectives for 2017. This has been the case even in the face of political tensions at home stalling the budgetary process and any meaningful momentum on fiscal reform. On the basis of execution data for the first quarter of 2018, budgetary projections and possible amendments to further increase spending, compliance with fiscal targets for 2018 is far from guaranteed. Over the medium term, the latest Stability Programme envisions convergence to a balanced budget by 2021, but with little adjustment to reduce the structural deficit. Such a scenario raises concerns over the evolution and ultimate sustainability of Spain’s public debt, having increased significantly over the crisis to reach close to 100% of GDP. Under the baseline scenario, public debt to GDP would converge to just below 80% over the upcoming ten-year period, rising to a further 85% or more should the economy experience a growth or interest rate shock.

IntroductionFiscal consolidation in Spain has taken place in the context of a contrasting environment during the last three years. On the one hand, the economic situation is clearly positive. Since 2015, Spanish GDP growth has been one of the most vigorous in the European Union. The economy has reached its pre-crisis level of GDP and in 2018 the output gap will be positive again, according to official estimates

[1]. Interest rates are at historic lows, which dramatically reduces the public debt burden. In tandem with this, the European Commission has been flexible in its demands for deficit reduction targets. One only needs to compare the course set out in the Fiscal Stability Programme of the Kingdom of Spain for the four-year period 2015-2018 with the levels attained and the target for the current year: a relaxation of the figures of between one and a half and two percentage points of GDP.

In contrast, the political context is more complex than ever before. The General State Budget (PGE) for 2016 was approved a quarter earlier than usual, in anticipation that the general elections held in December 2016 would put a break on the budget cycle. The opposite has happened in the following two years. The first six months of 2017 and 2018 have been managed with an extended budget, which implies strategic inaction and provisionality. In the last two years, the Parliamentary fragmentation has made it impossible to discuss and approve important reforms on both the revenue side and the public expenditure side: the tax system, regional financing and pensions. These are pending key reforms with no prospect of a short-term solution.

In short, it is true that Spain has met public deficit targets, but this is largely because the targets have been substantially relaxed and the economic situation has been even better than expected. The effort on the part of the administration itself could be stronger.

The aim of this paper is precisely to review the targets and trends of the Spanish fiscal framework in the short, medium and long term, starting with a brief review of the budget execution in 2017 and the first months of 2018. There is then an assessment of the picture depicted in the General State Budget (PGE-2018) and its parliamentary procedure; next, the medium-term scenario of the 2018-2021 Fiscal Stability Programme; and, lastly, reference is made to projections for the evolution of the public debt until 2027.

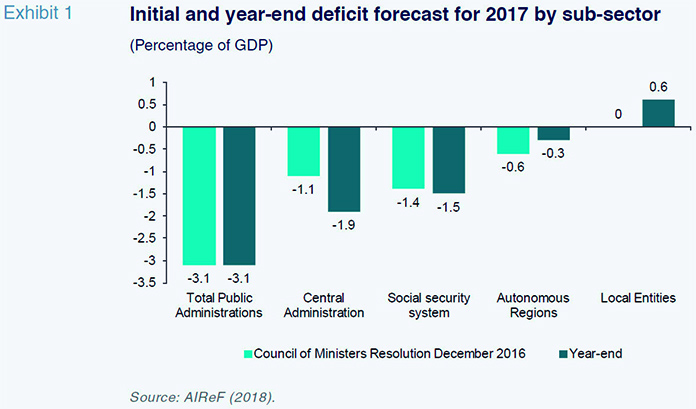

2017 year-end and the start of 2018As shown in Exhibit 1, the Spanish Public Administrations met the target (-3.1%) at the end of 2017. The results should not be surprising. Already in the second half of 2017, most public and private organizations were forecasting the achievement of the overall target for the entire year (Lago-Peñas, 2017). Nor should it come as a surprise that there has been notable diversity in the degree of compliance by sub-sectors, although it is true that the year-end result for the Autonomous Regions was in line with the most favourable expectations. In any case, the systematic deviation from the targets of some sub-sectors that we have seen in the last three years (in particular, in the case of Local Corporations and the social security system) should cause one to reflect on how realistic the targets of each sub-sector are. A systematically biased fiscal strategy ends up generating credibility problems and expectations of laxity in the compliance requirement

[2]. Using the surplus of one level of government (local) to offset deviations from others is a possibility. The alternative is that each sub-sector is tied to its own targets and that possible positive deviations are used to accelerate the reduction of the combined deficit of the Public Administrations. As we will see in later sections of this article, the second possibility is a better response to the slowness characterising the fiscal consolidation process in Spain.

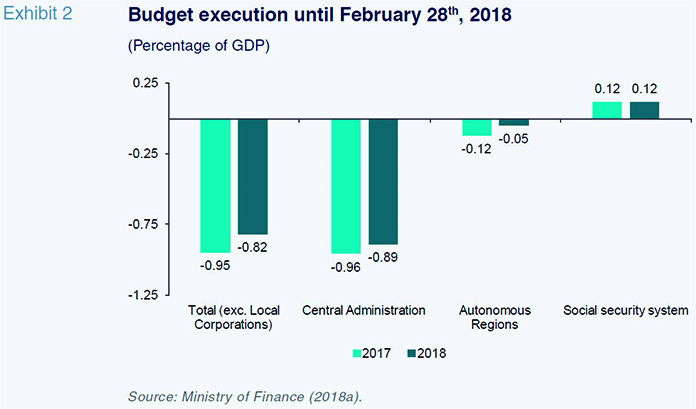

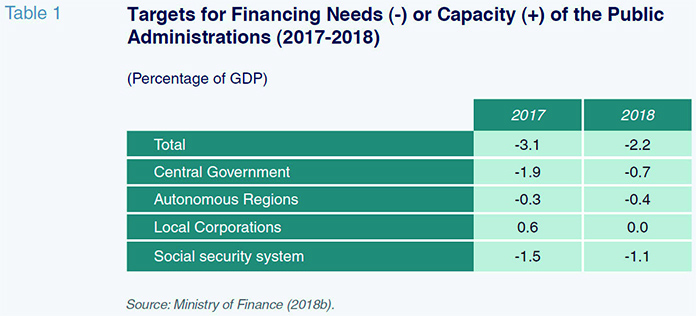

With regard to the current year, the information available on budget execution is limited to the first two months and disregards the Local Corporations. The target set for 2018 is to reduce the deficit by 0.9 percentage points, from -3.1% to -2.2%. In the first two months of 2018, the accumulated correction is slightly below one sixth (0.13 percentage points), a reduction that is shared almost equally between the Central Administration and the Autonomous Regions (Exhibit 2).

In May 2018, the Funcas’ consensus forecasts panel (2018) forecasted a minor shortfall of 0.3 percentage points (-2.5%), although the range of values is broad, from -2.2% to -2.8%. Both the Bank of Spain (2018) projections made public in March and the Fiscal Monitor presented in April by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2018) coincide with the Funcas’ consensus.

The recent evaluation by the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF) (2018), prior to the parliamentary debate of the 2018 General State Budget, considered compliance with the stability target to be “tight but feasible”, with a probability of 40% and a confidence interval for its forecasts with a central point also around -2.5%. The projections of the AIReF point again to a surplus of the Local Corporations similar to that of 2017

[3], which would offset a very probable non-compliance by the social security system and a probable non-compliance by the Central Administration.

Elaborating on this rise in the forecasts over various months, in the first week of May the European Commission (2018b) criticised the tone of the budgetary measures contained in the draft 2018 General State Budget and forecasted a deficit of -2.6%, even before the rise in pensions to which we will refer in the following section, and a structural imbalance increasing from -3.0% to -3.3%.

In short, with the partial information on execution for the first quarter and the projections, the budgets of the Autonomous Regions and Local Corporations and the draft 2018 General State Budget entering Parliament, compliance would not be guaranteed; in fact, it is not the most likely scenario. And the situation is complicated further because the draft 2018 General State Budget is being amended with measures that raise spending and that have not yet been considered in the previous projections. The upcoming section elaborates on this point as it refers to the Update of the 2018-2021 Stability Programme submitted to the European Commission on April 30th, 2018.

The impact of the parliamentary debate over the 2018 General State Budget

Parliamentary fragmentation has made the process of budgetary debate the key to the approval of the 2018 General State Budget. At the expense of additional changes, the extraordinary increase in pensions in 2018 (+ 1.6%) and 2019 (+ 1.5%) is clearly much higher than the 0.25% contained in the draft General State Budget presented to Parliament. The cost of the measure is 1,522 million euros in 2018 and 2,200 million euros in 2019 (Ministry of Finance, 2018b, Section 4.2.3).

This amendment gives rise to at least two problems. Firstly, it ignores the reform of the pension system approved by the Government in 2013. If at that point the urgency of the moment (in the middle of the European financial crisis, with the Spanish economy at risk of a bailout) could justify executive decisions being taken regardless of the so-called “Toledo Pact”, the logical thing now would have been to transfer the possibility of flexibility in the revaluation of pensions to this area of political consensus. Secondly, it is difficult to accept that a decision involving an accumulated growth in expenditure of 3 tenths of GDP is not accompanied by a complete and rigorous description of its financing. In a context in which compliance with deficit targets and the credibility of the budget is at stake, the brief and vague explanation on financing sources could damage the reputation of the fiscal consolidation strategy. Budgetary coherence requires further explanation, in additional to the 600 million euros already expected in 2018 arising from the European Directive presented at the end of March (“Proposal for a Council Directive laying down rules concerning the corporate taxation of a significant digital presence”) and still being processed.

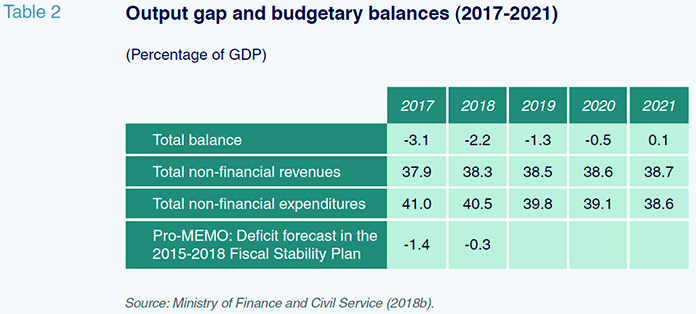

Medium-term outlook: The 2018-2021 Stability ProgrammeAs shown in Table 2, the 2018-2021 Stability Programme sets out a convergent evolution of expenditures and revenues to achieve a balanced budget (+ 0.1%) by the final year. The 3.2 percentage point change consists of an increase in revenues of 0.8 percentage points and a cut in the expenditure burden of 2.4%;

i.e., three quarters of the adjustment revolves around expenditure and one quarter around revenues. Moreover, the accumulated target delay is noteworthy. According to the 2015-2018 Fiscal Stability Programme, we would already be very close to balancing the budget (-0.3%), almost two points below the current target for the current year. And this is despite the favourable economic backdrop in which GDP has systematically grown more than forecasted in the General State Budget of each year

[4].

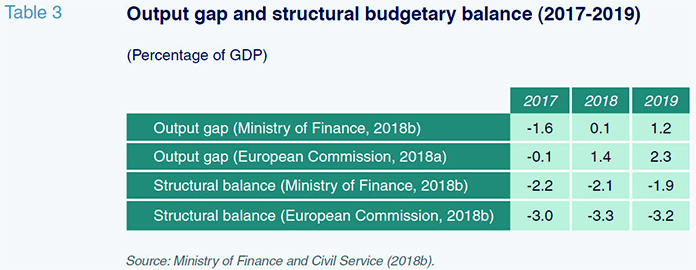

In fact, the main problem shown by the Stability Programme is the insufficient effort to reduce the structural deficit;

i.e., the deficit excluding the impact of the economic cycle. Table 3 shows the estimates of the Ministry of Finance and the European Commission, both of the output gap and the structural deficit for the 2017-2019 three-year period. Two conclusions stand out. The first is that the European Commission considers that Spain is already in a positive cyclical position and, therefore, the structural deficit in 2018 exceeds the total, because the cycle is helping. In contrast, the Ministry estimates that the position in 2018 is practically neutral and, therefore, the observed deficit coincides almost exactly with the structural one. Given the uncertainty that accompanies the output gap calculations, it is difficult to know which of the two estimates is more accurate, although it is true that the independent calculations of the AIReF (2018) are closer to those of the Ministry. Where there is greater consensus is in regard to the second conclusion: the deficit reduction in the 2017-2019 three-year period will be based almost exclusively on the improvement of the cyclical deficit, while the structural deficit appears to become entrenched. This entails a shortfall in the annual reduction of at least half a point of the structural component of the deficit required by European regulations, and hinders the reduction of the debt stock, as shown in the following section.

Fiscal stability beyond 2021

The long-term fiscal stability projections are particularly complex, because in addition to the uncertainty regarding the evolution of macroeconomic aggregates, there is a lack of definition of political objectives. Beyond 2021, we have no documents to guide future political decisions with budgetary impact. In fact, even those that exist are subject to a significant margin of error due to the very dynamics of democratic systems. However, the objective becomes simpler if instead of talking about deficit, we focus on debt dynamics. This is a more easily simulated magnitude, because inertia and the weight of the past are substantially greater than in the deficit. In particular, Spain has accumulated financial liabilities extraordinarily quickly: in 10 years it has gone from being one of the European economies with the lowest public debt to being one of the most indebted, with financial liabilities that by the end of 2017 were close to 100% of GDP.

Such a high level of debt to GDP is a cause for concern for five reasons. First, because of the interest charges that it entails. A normalization of rates in the euro area would quickly and substantially increase the interest bill, reducing the level of discretionary spending in the budget. Second, because of the instability it can generate in the event of a financial markets shock, as was demonstrated a few years ago through the resulting rise in the sovereign risk premium. Third, because it reduces the scope for fiscal stabilization policy in the face of future economic crises. Fourth, because the maximum benchmark for public debt in the euro area is 60%, almost forty points below the current figure. And fifth, because the progressive aging of the population represents a contingent liability that will progressively result in greater expenditure on pensions, health and care of dependent persons over the next three decades (Hernández de Cos et al., 2018). Obviously, the lower the public debt and the less demanding the pending fiscal consolidation, the greater the capacity of public finances to face this future challenge.

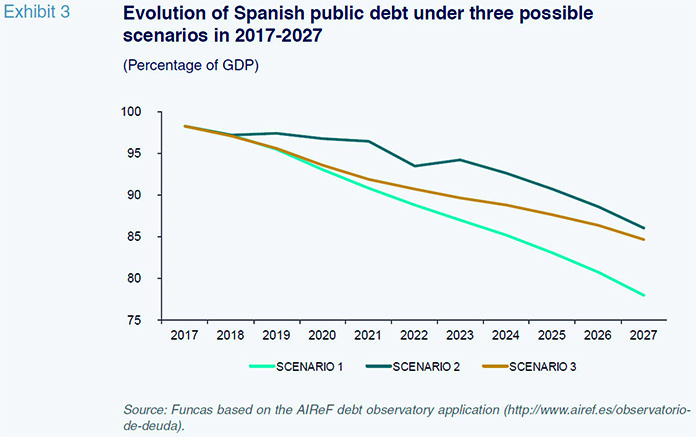

Therefore, it is worth analysing the expected evolution of the public debt over the upcoming 10-year period under different scenarios (Exhibit 3, prepared using the interactive public debt observatory application provided by AIReF)

[5]. Specifically, three scenarios have been simulated. The baseline scenario, the stressed scenario resulting from a slowdown in nominal GDP growth with respect to the baseline scenario, and another scenario in which the stress is caused by an interest rate shock

[6]. Undoubtedly, the results depend on multiple assumptions. But the fundamental story holds true. Without a radical change in the structural deficit targets, a decade will be clearly insufficient not only to return to the debt level of ten years earlier (35.6% of GDP), but also to reach the 60% threshold. In the neutral scenario, in 2027 public debt would remain at 78% of GDP. And the figure would increase to 85% or more in the event that one of the simulated shocks materializes.

The recent European Commission simulations (European Commission, 2018a) show an even more worrying scenario. Projecting the current primary deficit (i.e., excluding interest payments), the debt ratio in the central scenario would not fall below 95% in 2028. A very similar message is that emanating from the projections of Hernández de Cos, López-Rodríguez and Pérez (2018). Even in a scenario of 3% average nominal growth, with implicit interest rates on the public debt that are low from a historical perspective (2.5%) and a significant primary surplus (0.8%), the debt would not fall below 85% of Spanish GDP in 2027.

In short, fiscal stability targets in Spain are not very ambitious, taking into account both the current and forecast objectives and the enormous amount of public debt accumulated over the last decade. Greater rigour is required, and the government must decide, responsibly and coherently, whether the adjustment will come from increasing revenues or cutting expenditures.

The reality is that, on both fronts, the margin for reforms and improvements is substantial. There is consensus on the weaknesses of the Spanish tax system and the recent report of the European Commission (2018) focuses on two of them: the low VAT collection due to tax fraud and the scope of reduced rates, and weak “green taxation” in comparative terms. But the list of challenges and opportunities is very long and covers almost all taxes, as shown in the recent Funcas document (2017).

On the expenditure side, the challenge is threefold. First, to advance in the culture of evaluating public policies, permitting an increase in the social return of investments and current expenditure programmes

[7]. Second, to enhance coherency between the rights and the portfolio of public services that are embodied in the legislation and the resources that are used; between the welfare state that is desired and what people are collectively willing to really invest in it. Finally, there are areas in which the resource deficit is most notable from an international perspective (Lago-Peñas and Martínez-Vázquez, 2016). In particular, in investment in R&D+i, family policy, income programmes to fight social exclusion, and education.

Notes

According to the European Commission (2018), the output gap reached -8.2% in the two-year period 2013-2014, and underwent a correction to -0.1% in 2017 and +1.4% in 2018. The Spanish government in the 2018-2021 Fiscal Stability Programme reduced these figures to -1.6% and +0.1%. The GDP growth observed in 2014 went from -0.2% to +3.4% in 2015, +3.3% in 2016 and +3.1% in 2017.

AIReF (2018) gives a similar view.

In March 2018, a decree-law was approved that makes the expenditure rule of the Local Corporations more flexible and allows an increase in their investments. However, AIReF estimates that the impact in 2018 will be only 200 million euros and that it will have little effect on the surplus due to the good performance of operating expenses.

The change to the targets was agreed in the European Council of August 8th, 2016. The justifications given by the Government include a substantially lower than expected inflation rate; although real GDP grew more than expected, nominal GDP (the denominator of the ratios that are set as targets) grew less than expected.

According to the AIReF methodological note, in Scenario 1, the primary balance (balance excluding interest on the debt) evolves gradually and in line with the achievement of the long-term debt target. During the convergence process, the annual change in the primary balance tends towards 0.25% of GDP per year. In addition, it is assumed that the GDP converges gradually from its current values to approximately its potential in 2018, and then its growth in nominal terms stabilizes around 3.3%, with long-term inflation of 1.8%. In Scenario 2, a reduction in the real growth of the economy of 1% and 0.5% in the GDP deflator for 2017 to 2019 is applied. From 2020, GDP gradually converges to its potential level. Finally, Scenario 3 assumes an increase in the interest rates applied to financing requirements, differentiating between the administrations that are indebted in the market (average increase of 0.5% in rates) and those that receive financing through government support mechanisms (average increase of 1%).

There is scope for progress in the “Action Plan for Public Administration Subsidy Spending Review (“Spending review”)” that the Government has entrusted to AIReF in compliance with the provisions of the 2017-2020 Stability Programme (

http://www.airef.es/spending-review).

References

AIReF (2018),

Informe de los proyectos y líneas fundamentales de los Presupuestos de las Administraciones Públicas: Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales del Estado 2018, 17-4-2018,

http://www.airef.esBANK OF SPAIN (2018), “Proyecciones macroeconómicas de España (2018-2020),” March,

www.bde.es EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2018a),

Country Report Spain 2018, 7-3-2018, SWD(2018)207 at the end,

https://ec.europa.eu — (2018b),

European Economic Forecast. Spring 2018, https://ec.europa.eu FUNCAS (2017), “La teoría económica de las reformas fiscales: Análisis y aplicaciones para España,”

Papeles de Economía Española, 154,

www.funcas.es — (2018),

Panel de previsiones de la economía española, Mayo,

www.funcas.es HERNÁNDEZ DE COS, P.; LÓPEZ-RODRÍGUEZ, D., and J. PÉREZ (2018), “Los retos del desapalancamiento público,”

Occasional Papers, 1803, Bank of Spain,

www.bde.es IMF (2018), Fiscal Monitor, April,

www.imf.org LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2017), “Fiscal consolidation: Favourable economic conditions threatened by political uncertainty,”

SEFO, 6(6),

http://www.sefofuncas.com/Spain-A-closer-look-at-the-regional-dimension/Fiscal-consolidation-Favourable-economic-conditions-threatened-by-political-uncertainty LAGO-PEÑAS, S., and J. MARTÍNEZ-VÁZQUEZ (2016), “El gasto público en España en perspectiva comparada: ¿Gastamos lo suficiente? ¿Gastamos bien?,”

Papeles de Economía Española, 147: 2-25,

www.funcas.es MINISTRY OF FINANCE (2018a),

Ejecución presupuestaria del Estado hasta el mes de septiembre de 2017, 26-4-2018,

www.minhafp.gob.es — (2018b),

Actualización del Programa de Estabilidad 2018-2021, 30-4-2018,

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2018-european-semester-stability-programme-spain-es_0.pdf

Santiago Lago Peñas. Senior professor in applied economics and Director of GEN University of Vigo