Industrial production in the euro area: Navigating shocks, sectoral challenges, and global trade shifts

The euro area’s industrial sector, historically a pillar of economic strength, faces significant challenges in the wake of recent external shocks, with divergent performance across countries and sectors. Going forward, the outlook for the industrial sector remains uncertain; thus, requiring that country-specific policies be complemented with EU-wide strategies to support key industrial sectors, such as the automotive industry.

Abstract: The euro area’s industrial sector, historically a pillar of economic strength, faces significant challenges in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. These exogenous shocks have exposed structural weaknesses, causing a divergence in performance between countries and sectors. While Germany, France, and Italy have experienced notable declines in industrial output, Spain and smaller eurozone countries have demonstrated resilience, with positive industrial production figures derived in part from varying degrees of reliance on Russian energy. At the sectoral level, energy-intensive goods and intermediate products have faced the steepest declines, underscoring structural vulnerabilities, while non-durable consumer goods showed resilience due to lower sensitivity to business cycles. External trade dynamics are further complicating recovery, with additional trade headwinds from China potentially exacerbating existing tensions. Thus, as the region navigates these obstacles, it will be necessary to complement country-specific policies with EU-wide strategies to support key sectors, such as the automotive industry.

Foreword

The European economy is undergoing some notable changes. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine represent two major shocks that have exposed vulnerabilities and prompted structural shifts across sectors. The evolution of industry captures these dynamics in a representative way, and the recent announcement by Volkswagen of its plans to shut down several plants is a remarkable example.

The euro area’s industrial sector has long been a cornerstone of its economy. In 2023, it contributed around 19% of GDP and employed approximately 17% of the workforce. Europe’s industrial might has sustained its global standing, particularly in high-value sectors like automotive and machinery. Domestically, industry has reinforced the single market by driving cross-border supply chains and boosting productivity. However, recent years have revealed deep flaws in this growth model, as ECB Board Member Isabel Schnabel recently underscored (Schnabel, 2024) .

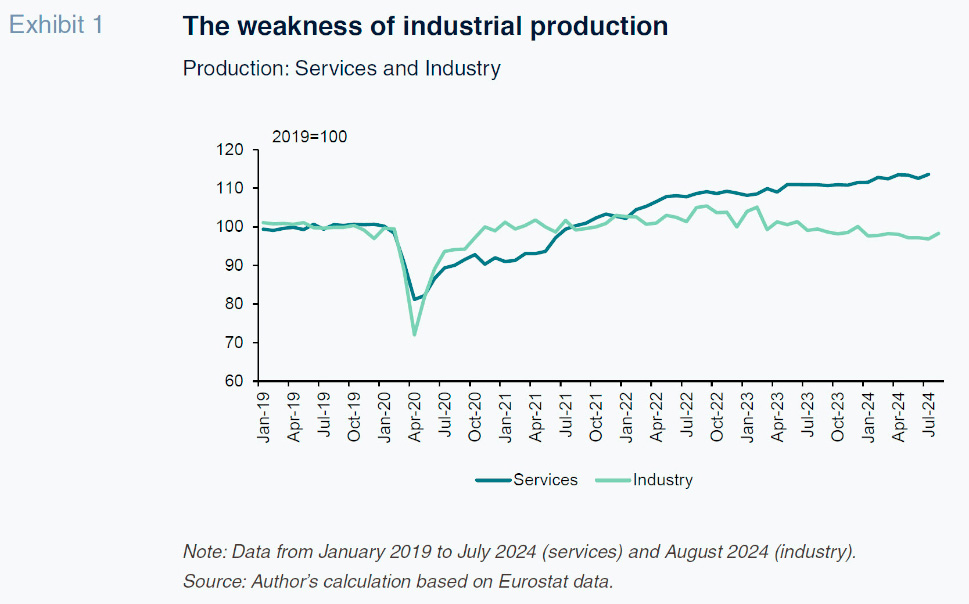

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine marked a critical turning point for euro area industrial production (see Exhibit 1). The health crisis led to a significant decline in the production of goods across the euro area, which was more pronounced than in services. This is somewhat surprising given the nature of the shock. The recovery in industrial production was faster than in services, although both sectors followed a similar pattern. However, a divergence began to emerge in 2022. While services experienced a remarkable dynamism, industrial production began to stagnate and had not recovered to its pre-pandemic level by 2024. This development may explain the uneven economic performance across Member States, with those more dependent on services (

e.g., Spain and Greece) performing better.

A potential limiting factor could be the behaviour of external demand. The weakness of some of the euro area countries’ main trading partners would have had, and may continue to have, a negative impact on the overall industrial performance.

Understanding this uneven landscape is essential for charting the euro area’s economic future. The drag on industrial production poses a direct threat to the region’s short-term growth prospects, particularly for manufacturing-dependent countries. In the long-term, this imbalance could exacerbate regional disparities if they are not properly addressed. Navigating these complexities will be crucial if the eurozone is to maintain a competitive industrial base and achieve a sustainable recovery in the coming years. In addition, the industrial performance is directly linked to the climate change objectives pursued by the Member States.

The aim of this article is to analyse the evolving challenges faced by the industrial sector in the euro area. More specifically, we shed some light on the different developments registered at the country and sector level, as these are key to better understand the overall performance. The remainder of the article presents: first, a geographical evaluation of industrial production; second, an illustration of the sectoral developments; third, an assessment of the factors that would explain the overall performance; fourth, an analysis of international trade to shed some light on how it could be related to industry; and, finally, an exploration of future developments.

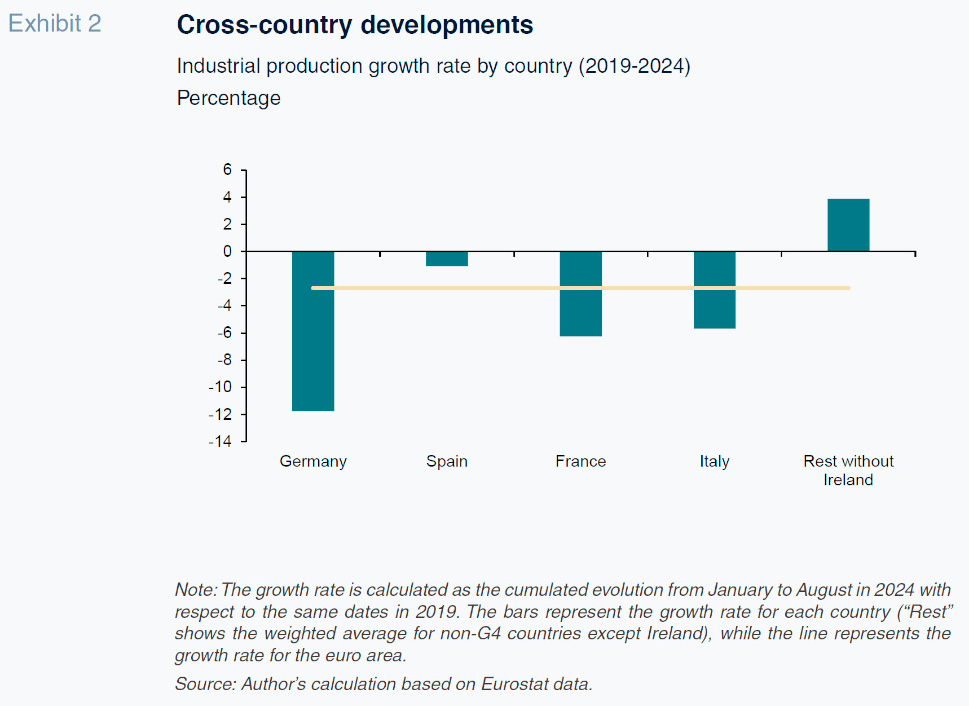

An uneven cross-country performance

G4 countries (Germany, Spain, France, and Italy), except Spain, have registered larger decreases than the euro area as a whole (see Exhibit 2). Germany and Italy, which represent more than 50% of the euro area’s total industry, have underperformed. Germany, in particular, may have been hard hit by the combination of rising energy prices and supply chain disruptions, leading to a contraction of approximately 12% in its industrial production over the past five years. Italy has also struggled, although its decline has been less severe (-5.7% from 2019 to 2024). In addition, France has also registered a notable decrease in industrial production (-6.3% in the past five years). These developments could explain, at least partially, the overall performance showed by the euro area.

In contrast, Spain has demonstrated stronger results (-1.1% from 2019 to 2024). One factor that would have contributed to the relative resilience compared with the other G4 countries is the lower exposure to Russian energy of the industrial sector.

Outside the G4, countries have outperformed the euro area since the COVID-19 pandemic, on average. However, there is a notable heterogeneity. Greece and, especially, Ireland have registered very good industrial production figures since 2019 (18.9% and 54.4%, respectively). On the contrary, Luxembourg, Estonia and Portugal have registered the largest decreases in industrial output within this group of countries (-14.1%, -7.6% and -6.5%, respectively, since 2019). Other countries such as the Netherlands have slightly increased its industrial production over the past five years (1.4% from 2019 to 2024).

Given its weight in the industrial sector of non-G4 countries, the role of Ireland is key to explaining this exceptionally good performance. Without the performance of Ireland, the rest of these countries would still have increased their industrial production, but to a lesser extent (3.9% since 2019).

Sector-specific developments

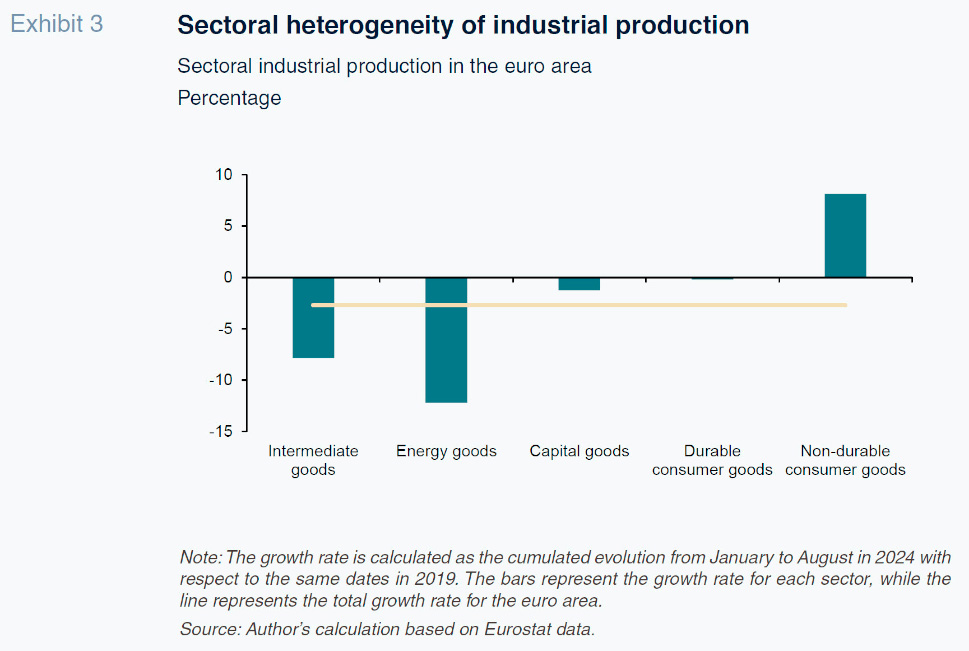

Further analysis by sector reveals additional insights into the euro area’s industrial path. All the major sectors, except non-durable consumer goods, have decreased their level of industrial production.

Intermediate and energy goods production declined notably more than the total eurozone’s output (-7.8% and -12.2%, respectively, between 2019 and 2024). These sectors play a crucial role in explaining the overall performance of industrial production. First, because they both represent more than 60%

of total production. Second, due to the nature of the energy shock, which is more related to the production of these goods. Thirdly, these goods tend to be inputs for the production of others, so this evolution may reflect a structural challenge for industrial production rather than a cyclical one.

These decreases, together with the weak performance of the capital goods sector, may have contributed to the overall decline in industrial production. Nonetheless, despite the rise in interest rates, which might have been expected to dampen its production, the output of capital goods has shown an unexpected relative resilience.

The production of non-durable consumer goods has provided a much-needed counterbalance to the broader slowdown in industrial output. These goods, such as basic household items, are less sensitive to business cycles and energy price volatility, which may have allowed this sector to behave better in recent years (8.1% since 2019).

The durable goods sector, however, has faced more significant challenges. Industrial production in this sector has remained practically the same over the past five years (-0.2%). Nonetheless, this figure could hide some heterogeneity. The European automotive industry, which is a key component of the durable goods sector, has struggled with rising input costs, semiconductor shortages, and supply chain disruptions

[1] .

In sum, geographical heterogeneity sheds some light on the weak evolution of industrial production. Nonetheless, the sectoral composition also seems to have played a role in recent developments in the euro area.

Who is pulling the weight?

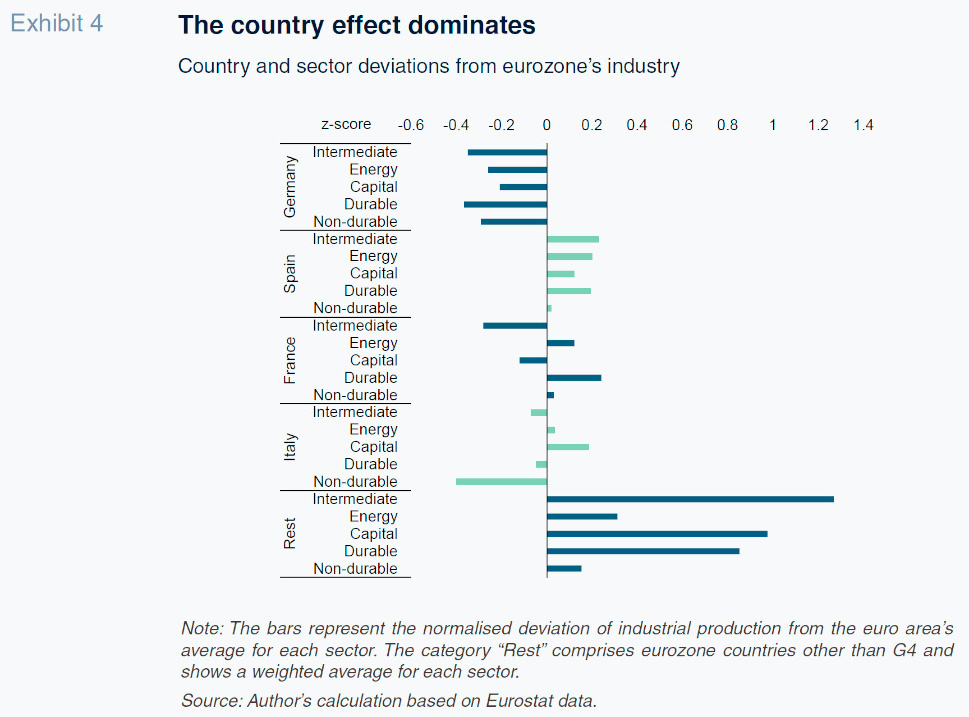

A crucial question that arises from these developments is whether they are driven by country-specific weaknesses (country effect), or by the underperformance of certain sectors (sectoral effect). The evidence (see Exhibit 4) leans towards a stronger country effect, suggesting that challenges within specific industries are having a less pronounced impact than a widespread national slowdown.

Germany, Europe’s industrial powerhouse, exhibits negative deviations from the euro area’s average across all major sectors, particularly in durable and intermediate goods. This widespread pattern of negative differences across all sectors highlights a comprehensive challenge within Germany’s industrial base. A potential explanation of this behaviour is the high sensitivity of the sectoral composition to the two major shocks that have occurred after 2020, and it would reflect the lack of a rapid reaction to them.

However, this weakness is not uniform across the other G4 countries, and this variation across countries underlines that no single national economy within the G4 is solely responsible for the overall industrial slowdown in the euro area.

Spain displays moderate positive deviations in most sectors, pointing to a more resilient industrial structure to the recent shocks. These figures would indicate that Spain’s performance would be less the result of country effects and more a reflection of positive sectoral dynamics within its industrial structure. These developments can be explained, at least partially, by how the Spanish industry employs production factors.

France shows a mix of sector-specific strengths and weaknesses rather than a consistent pattern of underperformance. The consumer (both durable and non-durable) and energy sectors stand out from the eurozone’s average. In contrast, intermediate and capital goods production present negative deviations from the euro area. This mixed pattern reinforces the idea that France’s industrial output is primarily shaped by sectoral effects.

Italy also demonstrates varied sectoral performance, rather than country effects. The production of intermediate goods and, especially, consumer non-durables present negative deviations. On the contrary, the energy and capital goods sectors outperform the euro area average.

Non-G4 countries stand out with positive deviations in all sectors. This strong performance shows that smaller countries are showing resilience and outperforming the euro area’s average industrial production. This behaviour contrasts sharply with that of the G4 countries, notably Germany, highlighting the differing industrial dynamics between eurozone countries. Also, these developments support the idea of strong country effects.

Nevertheless, industrial slowdown would also be driven by sectoral effects –even though the country dynamics dominate. In particular, the relative strength or weakness of specific factors –such as intermediate and consumer goods– would shape the industrial landscape across the eurozone. These findings highlight the importance of addressing sectoral challenges directly, as part of broad national policies. For instance, economic policies that promote innovation in the non-durable goods sector (e.g., car manufacturing production) can, at least partially, offset the negative trend in industrial output in the euro area.

All in all, the country effect would be the main factor that shapes industrial performance, as evidenced by consistent national deviations in Germany and non-G4 countries. However, understanding the role of external factors can also shed some light on how to help the industry to reverse these dynamics.

Trade headwinds

External economic relations have been essential to better understand the underlying dynamics of the Member States. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have underscored the need for many countries to rethink how they manage these relationships to guarantee an adequate provision of key goods and services. They are crucial to stay on track in the technological and ecological transition that the European Union and, by extension the euro area, is pursuing.

The eurozone’s trade of goods orientation was no exception to these global developments (see Exhibit 5, panel a). The G4 countries have shown different developments. Germany’s total import orientation has slightly decreased since 2019 (-1.2%). On the contrary, Italy has registered a notable increase in the share of goods imports in the recent years (13.8% since 2019). Spain and France have relatively increased their imports of goods over the last five years (3.8% and 0.9%, respectively). For their part, countries other than the G4 show an overall reduction in import dependence.

The story is slightly different for total export orientation, which has generally declined. Germany, France and the non-G4 countries have reduced their total export orientation (-2.5%, -4.4% and -2.0% respectively since 2019). In contrast, Spain and, especially, Italy have increased their goods export orientation over the last five years (1.9% and 10.8% respectively). This behaviour may reflect a strategic shift to other markets in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Another relevant insight is the development of goods sales to China (see Exhibit 5, panel b). The share of exports to China as a share of each country’s total extra-eurozone exports declined for all G4 countries except France. Germany registered the largest fall (-14.9%), while Italy and Spain both reduced their shares by around 8% each. France’s share of sales to China remained practically unaltered over the last five years.

The rest of the countries have also decreased their exports to China since 2019 (-12.3 %). These reductions may be related to the weakness of Chinese demand, as the Asian country is struggling with national demand.

The exposure of the eurozone to China has been widely documented (for example, Sandkamp, 2024 or Vandermeeren, 2024). One of the main characteristics of the commercial ties between the two areas is the persistent deficit of the euro area with China, especially in goods, although this figure is unequal among Member States. For goods, Germany, France, and the Czech Republic have the largest deficits, which reflects that countries with more industrialised economies tend to be more dependent on China.

The last five years have been a turmoil for the international stage, with various shocks –health and energy– hitting the world economy. The euro area has reacted to these events by maintaining practically unaltered the share of goods coming from, and to, the rest of the world, and modifying its composition. The whole picture shows that the euro area’s relationship with China is characterised by different dynamics. First, the lower number of good exports accounted for by Germany, Spain and Italy, may reflect the reduction in demand experienced by China. Despite the efforts made by the Chinese authorities, the slowdown in consumption may have an impact on the industrial sector of the euro area via exports of goods. Second, the imposition of duties on Chinese cars may aggravate these developments. On the one hand, because they are designed to reduce imports. On the other hand, because they may lead to a tariff war that could further reduce exports to the Asian country.

Looking ahead

The euro area has experienced two major shocks that have affected industrial production in recent years. The evidence presented in this article suggests that the decline is mainly explained by country-specific rather than sectoral factors. This would motivate the application of policies focused primarily on addressing structural and economic factors unique to each country. Such an approach could enhance resilience by aligning support with the specific needs and vulnerabilities of individual economies, and ultimately promote a more balanced recovery across the euro area. It would go against the proliferation of State Aid which has spread in recent years, without much impact on the performance of most-affected countries –a policy which also runs risk of fragmenting the Single Market.

Nevertheless, sectoral composition could also be relevant. In particular, the automobile industry seems to be facing significant challenges in the euro area as a whole. This would suggest the relevance of EU-wide policies to support technological change and innovation (see Torres, 2024).

Another complication is the region’s external trade performance, particularly with China and the US. Trade barriers and the evolution of Chinese demand will provide additional headwinds, further straining the ability of the industrial sector to fully recover. In this regard, China’s reaction to European tariffs represents a downside risk in the next years. A 10% general increase in Chinese tariffs could reduce G4 GDP by 0.3% on average (Schumacher and Dezeure, 2024). Additionally, the sectoral composition of these obstacles may exacerbate the negative effects.

Potential protectionist measures established by the new US administration would pose an additional challenge. A 10% general increase in US tariffs could reduce G4 GDP by 0.4% on average (Schumacher and Dezeure, 2024).

However, the final impact will be conditioned on the behaviour of several dynamic factors such as the EU’s strategic response and exchange rate developments.

The goal should not only be to get over the current cyclical moment, but also to ensure a lasting turnaround. The guidelines proposed in Mario Draghi’s recent report on European competitiveness and Enrico Letta’s document on the single market are a good example of how these proposals can be implemented in more concrete terms.

Notes

[1] For further analysis, see Torres (2024).

References

SANDKAMP, A. N. (2024). EU-China trade relations: Where do we stand, where should we go?

Kiel Policy Brief, No. 176. Kiel: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel).

https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/297975/1/1890798258.pdfSCHNABEL, I. (2024). Escaping stagnation: towards a stronger euro area. Speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at a a lecture in memory of Walter Eucken (

Freiburg, 2 October 2024). ECB.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2024/html/

ecb.sp241002_2~4fbb6ea450.en.htmlSHUMACHER, D., and DEZEURE, N. (2024). Europe: How much damage could tariff hikes cause?

SUERF Policy Note Issue, No 353, July 2024. SUERF The European Money and Finance Forum.

https://www.suerf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/SUERF-Policy-Note_Issue-353_Schumacher-Dezeure.pdfTORRES, R. (2024). Europe’s automotive industry in the face of competition from the US and China.

Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook, 13(5), 39-46.

https://www.sefofuncas.com/Spanish-banks-Navigating-uncertainty/Europes-automotive-industry-in-the-face-of-competition-from-the-US-and-ChinaVANDERMEEREN, F. (2024). Understanding EU-China exposure Single Market Economics Briefs.

Economic Brief, 4. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2024.

https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2024-01/EconomicBrief_4_ETBD_23_004ENN_V2.pdf

Miguel Ángel González Simón. Funcas