Spain’s household and corporate accounts in 2024: Diverging growth paths

In 2024, Spain’s households continued to build financial strength through rising incomes, high savings, and manageable debt burdens. Meanwhile, non-financial corporations faced falling profitability and persistently weak investment, revealing a growing imbalance in the post-pandemic recovery.

Abstract: Against the backdrop of impressive GDP growth in Spain in 2024, household incomes grew strongly for a second consecutive year, supported by wage gains, rising property income, and easing inflation. This trend led to a significant increase in savings and a record-high net lending position. Despite higher interest payments, households remained financially sound, with debt ratios continuing to fall relative to income and GDP thanks to a growth in savings. In contrast, non-financial corporations saw a decline in gross operating surplus and weak investment dynamics, with real capital formation still lagging pre-pandemic levels. While corporate dividend payouts reached record highs, retained earnings fell, suggesting limited reinvestment capacity. Overall, 2024 revealed a growing divergence between household financial resilience and corporate underperformance, pointing to a structural shift in Spain’s post-pandemic economic landscape.

General background

In 2024, Spanish GDP increased by 3.2%, which is well above the eurozone average and also above the level forecast at the start of the year. There are three key explanatory factors: higher-than-forecast growth in both tourism and public spending and demographic growth as a result of intense immigration. Employment and average compensation per jobholder also registered healthy growth, despite slowing a little from 2023, while inflation eased from 3.5% in 2023 to 2.8%. The let-up in inflation across the eurozone allowed the European Central Bank to start to lower its interest rates in June, having peaked at 4% in September 2023.

In this paper, we analyse the trend in the accounts of Spain’s households and non-financial corporations (NFCs) in 2024 using the non-financial accounts by institutional sector compiled by Spain’s statistics office, the INE, following the same methodology and conventions as are used in the national accounts.

Consumption tapered as household income grew

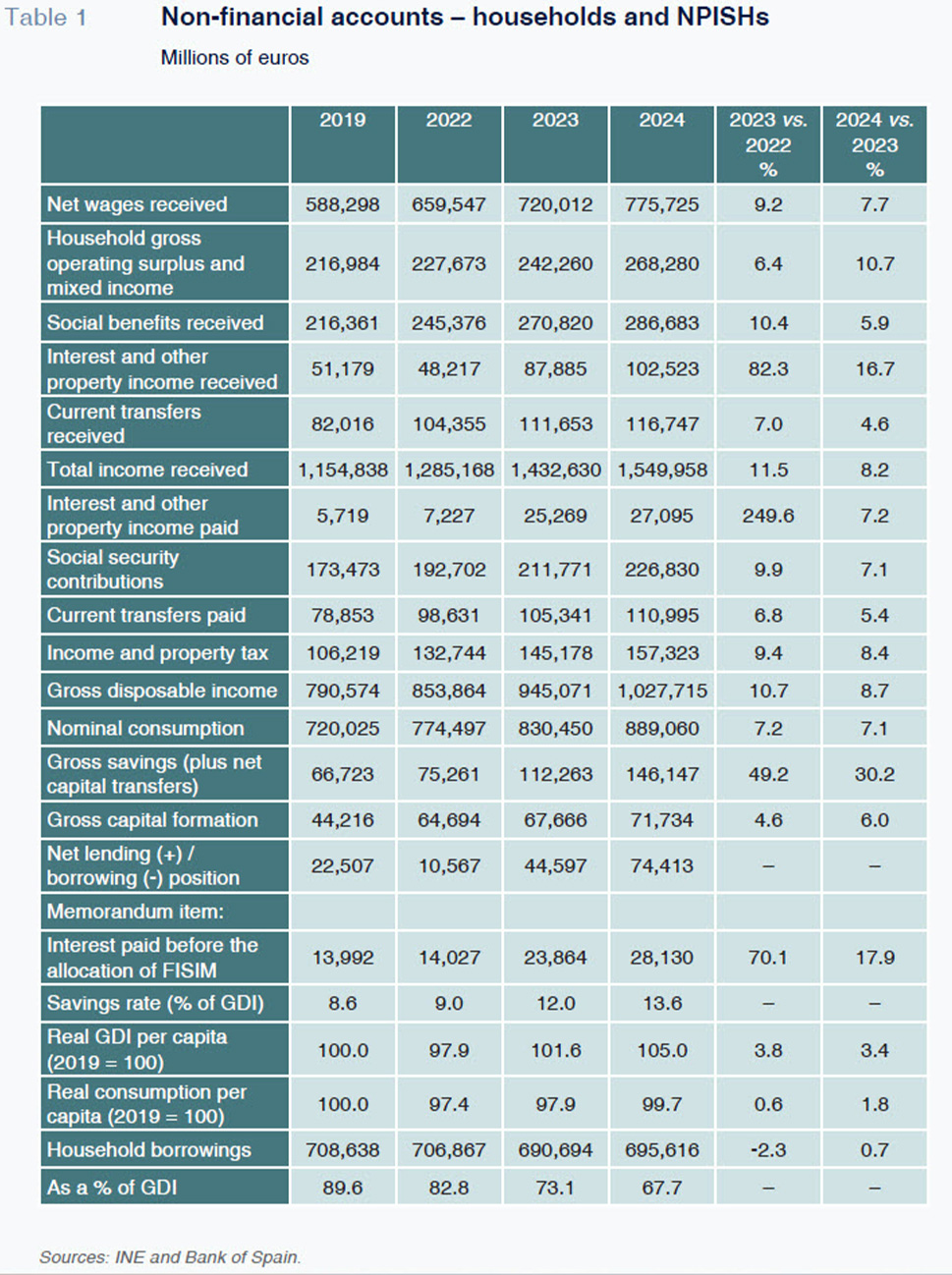

Before analysing the household sector’s accounts for 2024, we need to point out that the figures for 2023, analysed by Fernández (2024), have since been revised by the INE. More specifically, the main components of household income were revised upwards: employee compensation, gross operating surplus, mixed income and social benefits. Although other elements that reduce income (interest payments and social security contributions, for example) were also revised upwards, the net impact was an increase in the household sector’s gross disposable income (GDI) with respect to the initially published figures. Despite the revisions, the analysis provided in the original paper remains valid; if anything, the conclusions reached have been reinforced.

Turning back to 2024, the net wages earned by Spanish households registered intense growth, of 7.7%, albeit easing from the 2023 figure, shaped by lower growth in both employment and average wages per jobholder. The latter, despite the slowdown, continued to register strong growth by historical standards, of 5% according to the national accounting figures. In the entire series, which goes back as far as 1995, there was just one year, 2009, aside from 2023, in which average earnings rose faster than 5%. Earnings also rose by more than prices for the second year in a row, allowing average wages to fully recover the purchasing power lost in the previous years of high inflation.

Property income – both interest income and dividends and other income – also registered strong growth, doubling the amounts collected in 2019. Growth in social benefits slowed considerably from 2023, heavily influenced by the restatement of pensions in 2023 for the inflation recorded in 2022 (Table 1).

Interest payments (before the FISIM allocation) increased by €4.27 billion, shaped by the increase in the average effective borrowing rate. Although 12-month Euribor began to trend lower at the end of 2023 in anticipation of the ECB rate cuts that ultimately materialised mid-2024, the average effective rate paid by households increased last year due to the lag in the repricing of floating-rate loans to reflect movements in official rates. The growth in interest payments is not attributable to an increase in borrowing levels: although the balance outstanding at the end of the year was higher than at year-end 2023 (Table 1), the balance was consistently lower year-on-year throughout the rest of 2024, only rising year-on-year in the last quarter.

The debt service burden, relative to GDI, increased for the second year in a row to the highest level in 10 years; however, as was the case in 2023, the increase was easily absorbed, on aggregate, thanks to the growth in household income. This is borne out in the downtrend in non-performance on mortgage loans, which started the year at 2.7% and ended it at 2.4%. The non-performing ratio on consumer credit also came down last year. According to the Bank of Spain (2025), the percentage of indebted households that have to set aside more than 40% of their income to service their debt decreased in 2024 from 2022 and dipped below the 2014-2022 average.

Elsewhere, the taxes paid by households on their income and wealth increased by 8.4% in 2024, which is just below the growth in taxable income (the latter calculated using the national account figures), paving the way for a slight decrease in the average effective tax rate, which nevertheless remains close to record highs. Social security contributions (which in national accounting terms include both the contributions paid by employers and those paid by employees within the compensation received by households) increased by 7.1%.

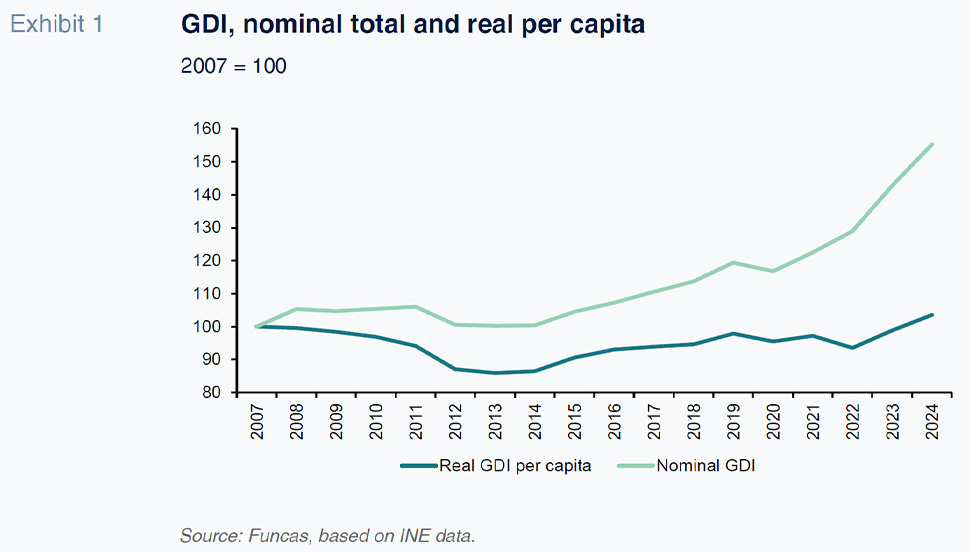

As a result (and factoring in the trend in transfers paid and received), nominal household gross disposable income registered growth of 8.7%, below the growth of 10.7% recorded in 2023 but still very high by historical standards. However, adjusting for inflation and population growth, real growth per capita falls to 4.8% (and if we use the consumption deflator instead of CPI, further again to 3.4%). As a result, for the first time, real GDI per capita exceeded (by 3.6%) the record levels of 2007-2008 (using the consumption deflator, that record was surpassed in 2023).

Returning to nominal figures, the growth in GDI was higher than the growth in consumption, paving the way for intense growth in savings. The household savings rate (savings as a percentage of GDI) rose to 13.6%, compared to 12% in 2023, well above the levels observed prior to the pandemic. The fact that the increase in the savings rate in the post-pandemic era is proving so persistent suggests that we are witnessing a largely structural phenomenon, which may be related, among other things, to demographic factors (García and Alcobé, 2025).

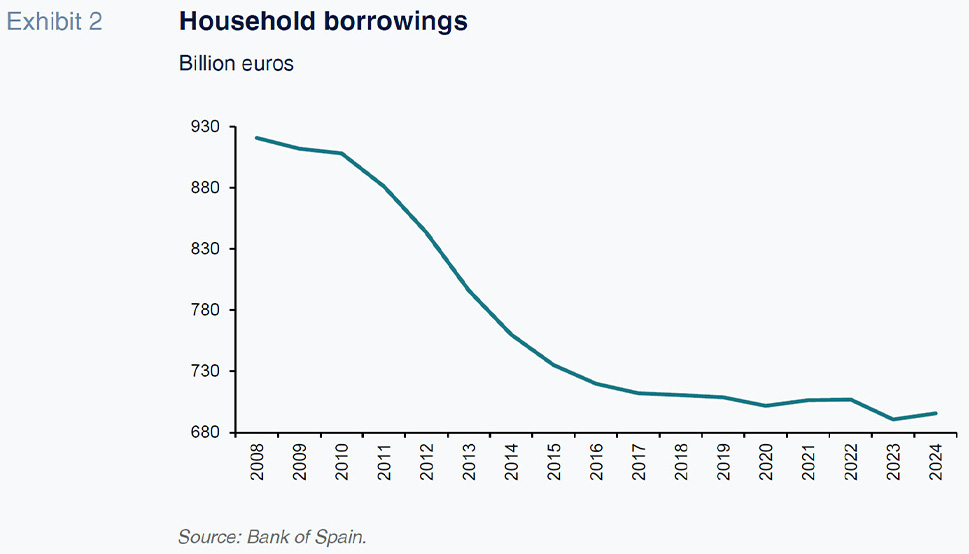

Roughly half of household savings was earmarked to GFCF, so that the household sector generated a net lending position – the difference between savings and investment – of €74.4 billion, which at 4.7% of GDP is the highest level in the entire series barring 2010. That surplus was used in full to purchase financial assets. In contrast to what we saw in 2023, Spanish households did not use their surplus to repay debt. To the contrary, their borrowings increased in nominal terms although they continued to come down as a percentage of GDP, to 43.7%, which is 7.8 points below the eurozone average.

Household deleveraging, which began in 2009, was uninterrupted in both nominal and relative (as a percent of GDI) terms until 2020. Since then, although borrowings have continued to come down in relative terms, the nominal balance has been up and down, indicating that the deleveraging process has probably come to an end, at least in nominal terms. From here on we are more likely to see debt trend more in line with the economic cycle (Exhibit 2).

Comparing the different variables with 2019 reveals that real GDI per capita was 5% higher in 2024, whereas real consumption per capita was still slightly below pre-pandemic levels. This means that all of the growth observed in consumption throughout this period (3.4% in real terms) has been driven by population growth (derived from a simple decomposition of the growth in the variable aggregate; it is conceivable that per-capita consumption of the citizens who were already residents has increased but that they spend less on average than the newcomers, yielding the above result).

Here it is worth highlighting the important role played by immigration in economic growth in Spain in recent years, on both the demand side (contributing to growth in consumption) and on the supply side, providing the manpower needed to enable the growth in other key engines of Spain’s economic growth, like tourism.

It is fair to say, in conclusion, that household behaviour in the last couple of years has been characterised by restrained spending in a context of income growth and financial health, unlocking growth in savings.

Slump in corporate profitability

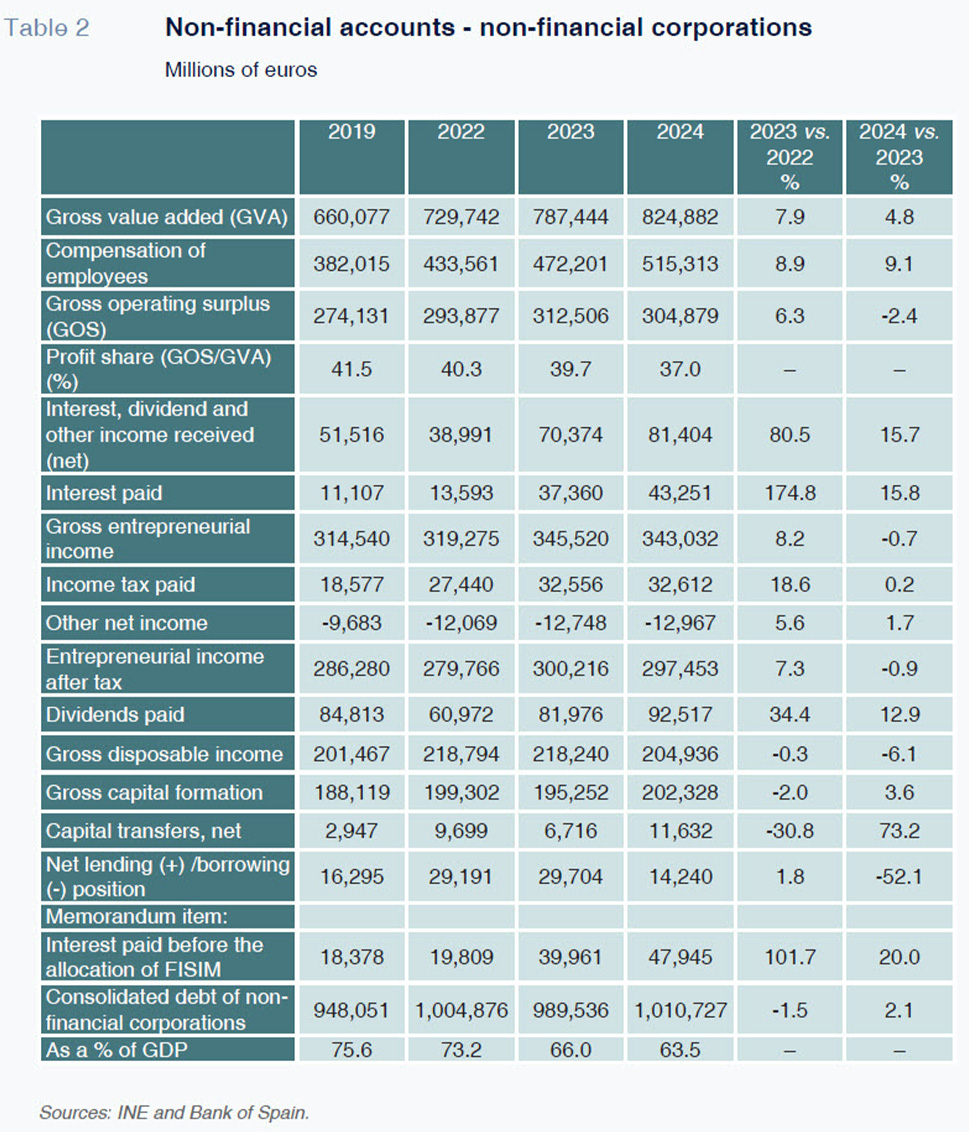

The non-financial corporation account figures for 2023 and prior years have also been revised upwards so that their gross operating surplus (GOS) was higher than initially estimated, as was their income, defined as the sum of GOS, interest and dividends collected and other net income, less interest paid. Nevertheless, the conclusions drawn in the analysis by Fernández (2024) continue to hold as regards the weak profitability of the non-financial corporations, the lag in growth by comparison with household income in both 2023 and in the cumulative period since 2019, and the frailty of corporate investment.

Returning to 2024, the accounts published by the INE indicate a contraction in the NFCs’ nominal GOS of 2.4% [1] (Table 2). As a percentage of GVA, the corporations’ GOS fell to 37%, down 2.7 percentage points from their profit share in 2023 and down 4.5 points from 2019.

The contraction in GOS was driven by higher growth in compensation of employees than in GVA. Although the corporations recorded growth in net finance income (thanks to interest and dividends), it was insufficient to offset the drop in GOS, so that gross entrepreneurial income before tax dipped by 0.7%.

Nevertheless, the NFCs increased their dividend payments sharply, to €92.5 billion, topping the pre-pandemic record of 2019 for the first time (in nominal terms; in real terms it has yet to revisit that record). As a result, the sector’s gross disposable income, which is essentially retained earnings, decreased by 6.1% to land just €3.5 billion above the 2019 figure. That sum, coupled with capital transfers received, which were substantially higher than the levels observed prior to 2019, due to the NGEU funds, was sufficient to finance gross fixed capital formation, which grew at very moderate levels in both real and nominal terms. Gross fixed capital formation (which excludes changes in stocks) registered slightly higher growth than total capital formation but remained notably weak. In real terms, the non-financial corporations’ GFCF was around 10% below 2019 levels.

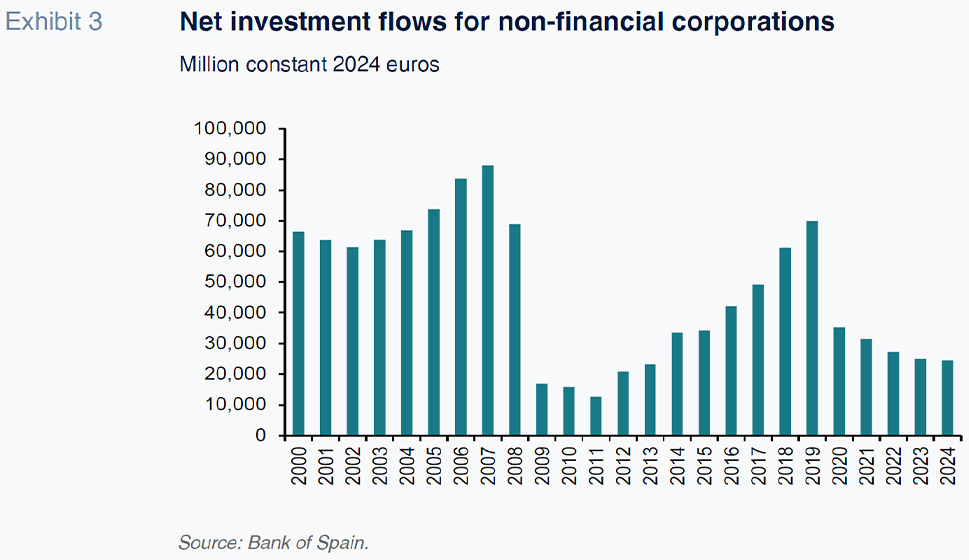

Subtracting the consumption of fixed capital, since 2021, net investment flows have been at record lows for this century, with the exception of the financial crisis between 2009 and 2013 (Exhibit 3). Vicente Salas (2024a and b) has analysed this phenomenon, citing the increase in the user cost of capital coupled with a drop in the return on capital as the causes of this weakness. It has also been analysed in detail by Domenech and Sicilia (2024), who pinpoint additional potential causes, including institutional deterioration.

Lastly, after paying for those investments, the non-financial corporations obtained a financial surplus of €14 billion, equivalent to 0.9% of GDP. That surplus was used mainly to acquire financial assets, although the businesses also increased their debt, albeit very slightly. As a result, corporate indebtedness as a percentage of GDP continued to trend lower, extending the pattern observed virtually non-stop since 2010 (leverage only ticked higher in 2020), to 63.5%, which is considerably below the European average, as is the case with household leverage.

Conclusions

2024 was marked by a similar pattern to that observed since the pandemic (with the exception of 2022): business earnings weakness in contrast to more robust growth in household income. Momentum in the household sector continued thanks to ongoing growth in employment and wages, which was more than sufficient to absorb the increase in interest payments on the back of higher rates (all in aggregate terms for the household sector as a whole and using the national account conventions).

Another trend that carried over to 2024 was the restraint in household spending so that, as income continued to rise, the sector’s savings rate consolidated at considerably higher levels than was usual prior to 2019, etching out what can now be described as a structural shift in the Spanish economy.

The non-financial corporations’ GOS and income trended lower in 2024. Entrepreneurial income after tax was a mere 3.9% above the 2019 equivalent in nominal terms, which is significantly below the inflation observed during the period.

Lastly, corporate investment, despite some growth, remains remarkably weak, lingering sharply below 2019 levels in real terms, running at rates that are barely enough to make up for the consumption of fixed capital and so maintain the stock of productive capital.

Notes

The Spanish economy’s total gross operating surplus increased by 4.1%, with that growth coming from the other institutional sectors —government, households and financial corporations— as the non-financial corporations’ GOS shrank.

References

BANK OF SPAIN. (2025).

Financial Stability Report. Spring 2025. https://www.bde.es/wbe/es/publicaciones/estabilidad-financiera-politica-macroprudencial/informe-estabilidad-financiera/informe-de-estabilidad-financiera-primavera-2025.html DOMENECH, R., and SICILIA, J. (2024).

Investment in Spain and in the EU. BBVA Research.

https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Observatorio_La-Inversion-productiva-en-Espana-ene2024_ENG_edi.pdf FERNÁNDEZ SANCHEZ, M. J. (2024). Spain’s household and non-financial corporate accounts for 2023.

SEFO, Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook, Vol.13, No. 3 (May 2024).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/Deep-dive-into-Spain%E2%80%99s-private-sector/Spains-household-and-non-financial-corporate-NFC-accounts-for-2023 GARCÍA ARENAS, J., and ALCOBÉ GARCIA, E. (2025). The rise in savings: magnitude, distribution and the importance of demographics.

Caixabank Research, January 2025.

https://www.caixabankresearch.com/en/economics-markets/activity-growth/rise-savings-magnitude-distribution-and-importance-demographics SALAS FUMÁS, V. (2024a). Capitalisation of Spanish corporations since the financial crisis.

SEFO, Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook, Vol.13, No. 3 (May 2024).

https://www.sefofuncas.com/Deep-dive-intSpain%E2%80%99s-private-sector/Capitalisation-of-Spanish-corporations-since-the-financial-crisis SALAS FUMÁS, V. (2024b).

Fixed capital formation in the non-financial corporate sector of the Spanish economy: crisis, recovery and prospects. Technical Note, 1/2024. Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Fixed-Capital-Formation_0424.pdf

María Jesús Fernández. Senior Economist at Funcas