Spain’s household and non-financial corporate (NFC) accounts for 2023

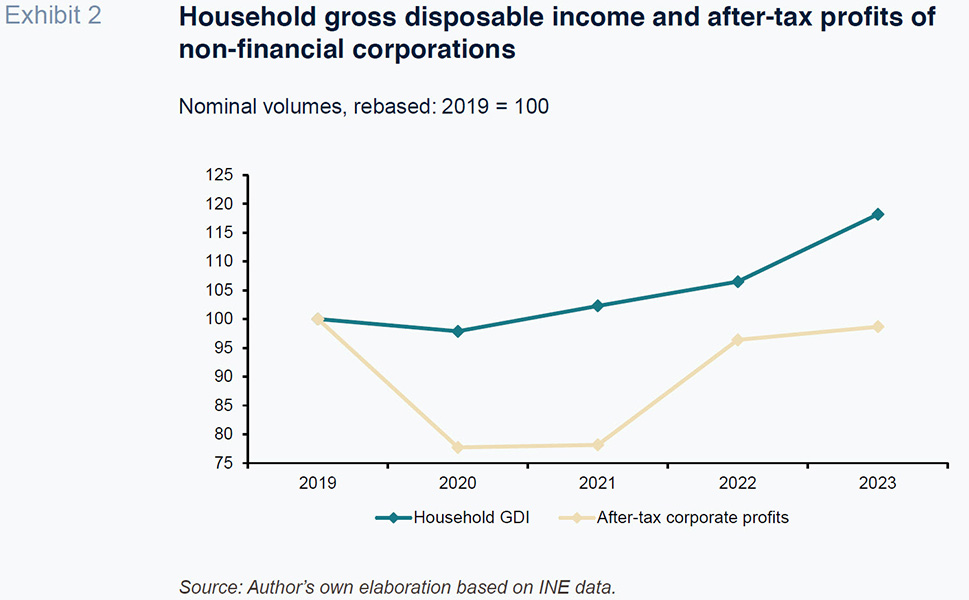

Whereas in 2022, corporate income registered significant growth, nearly revisiting pre-pandemic levels, in 2023, it was household income that was more dynamic. By comparison with 2019, in nominal terms, the income gap between the non-financial corporate (NFC) and household sectors widened, revealing an incomplete recovery in the corporate segment compared to solid growth in household income.

Abstract: Corporate income registered significant growth in 2022, making notable progress towards reaching pre-pandemic levels. However, in 2023, it was household income that was more dynamic. The trend in household income has been relatively favourable throughout the post-pandemic years, despite the increase in inflation. This has been largely attributable to the resilience of the Spanish labour market labour, as well as wage growth. These factors allowed Spain’s households to absorb the impact of the increase in interest rates in 2023 with relative ease, as evidenced by the stability in the rate of loan non-performance in this sector. As well, household debt, at 74.2% of GDI, reached its lowest level since 2001. In the corporate sector, however, the increase in rates had a more pronounced impact, although that is not the only reason for its relatively weak earnings performance. Indeed, Gross Operating Surplus (GOS) registered moderate growth, down significantly from 2022 and below the growth in the compensation and benefits received by Spanish households, which, in contrast, accelerated. By comparison with 2019, in nominal terms, the income gap between the non-financial corporate (NFC) and household sectors widened, revealing an incomplete recovery in the corporate segment compared to solid growth in household income. Lastly, investment levels at Spain’s corporations remain depressed, with firms preferring to use their profits to repay debt, despite already healthy leverage levels by both historical standards and by comparison with their European peers.

Background

The situation in the global energy product markets virtually normalised in 2023 following the crisis produced by the invasion of Ukraine the year before. This, coupled with monetary tightening, has curbed inflation, with the rate in Spain dropping from 8.4% in 2022 to 3.5% in 2023. The impact of the rate increases on the developed economies has been smaller than expected so that, despite the lethargic Eurozone economy, we can talk about a “soft landing”. Against this backdrop, Spanish GDP, which in 2022 revisited 2019 levels, registered growth of 2.5% in 2023, significantly above the Eurozone average of 0.5%, although the bloc as a whole revisited pre-pandemic GDP a year sooner than Spain. The Spanish and European economies once again presented remarkably resilient employment dynamics last year.

Employment, compensation and pensions drove growth in household income

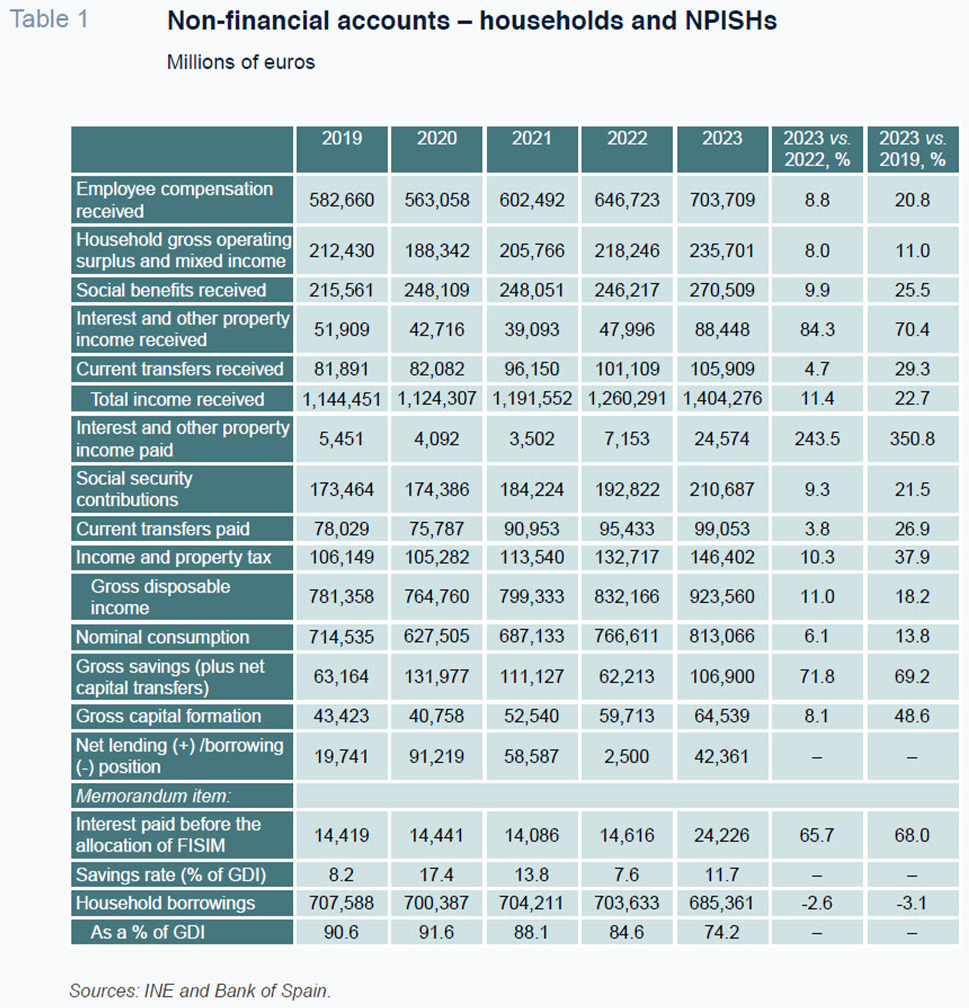

Before analysing the household sector’s accounts in 2023, we need to point out that the figures for 2022, analysed by Fernández (2023), have sustained slight corrections with respect to the numbers originally published by Spain’s Official Statistics Office (INE). The revised figures show that household gross disposable income (GDI) increased by more than initially reported, which translated into higher savings and, ultimately, a net lending position of 2.5 billion euros, rather than the initially estimated net borrowing requirement of 1.75 billion euros. Despite that change, the analysis provided in that paper remains valid and the conclusions drawn have not changed in any significant way.

Growth in household wage remuneration accelerated to 8.8% in 2023, thanks to a steady rate of growth in employment, coupled with higher wages per job holder (+5.4%). Property income also registered healthier growth, shaped by interest income and other income such as dividends. Indeed, dividend income totalled 24.8 billion euros, similar to the 2017 and 2018 figures but still below the 2019 equivalent. Among the other sources of household income, it is worth highlighting the sharp growth in social welfare benefits, mainly driven by the adjustment to pensions for 2022 inflation (Table 1).

Interest paid increased by 9.6 billion euros to 24.2 billion euros (before the Financial Intermediation Services Indirectly Measured —FISIM— allocation), shaped by higher interest rates on the back of monetary policy tightening. However, that increase was moderate by comparison with the growth in household income, and therefore did not prevent sizeable growth in GDI. It is fair to say, therefore, that the increase in interest rates has been absorbed with relative ease, in general terms, by Spanish households, as is further borne out by the stability in loan non-performance: the NPL ratio climbed just 0.2pp higher in 2023 to end the year at 2.6%, the lowest level in 12 years.

As for income and property tax paid by Spain’s households, this heading experienced double-digit growth once again in 2023, the difference being that whereas in 2022 payments increased by more than taxable income (calculated using the national accounting numbers) this year’s growth was more in line. Nevertheless, the effective income tax rate remains considerably above pre-pandemic levels. Social security payments did increase by a little more than wage earnings, possibly due to regulatory changes, such as introduction of the so-called intergenerational equity mechanism designed to replenish the pension coffers, among other things.

As a result, nominal GDI registered growth of 11% in 2023, outstripping inflation, so allowing households to recover some of the purchasing power lost the year before. That growth was also higher than the growth in nominal consumption, so that savings once again rose above the 100 billion mark, having diminished the year before. The savings rate came in at 11.7% of GDI, which is above the levels observed before the pandemic. It is still too early to tell whether the fact that savings rates have remained above pre-pandemic levels, a phenomenon observed virtually all across the EU, is a structural or temporary change.

Around 60% of those savings was earmarked to GFCF, so that the household sector generated a net lending position –the difference between savings and investment– of 42.36 billion euros. Most of this surplus was used to purchase financial assets but also, in a significant amount by historical standards, to repay debt. The household sector’s stock of outstanding debt therefore decreased, in nominal terms and in relation to its GDI. The latter ratio reached its lowest level since 2001, at 74.2%.

Comparing the various headings with respect to 2019 shows that nominal GDI has increased by 18.2%, which is more than consumer prices, so that household income has increased in real terms. That nominal growth is in line with the figures observed across the Eurozone. Nevertheless, due to population growth in Spain, real GDI per capita has only increased by a small margin, if we arrive at the real figure by using national accounting consumption as our deflator; if instead we use CPI, real GDI per capita is still slightly below 2019 levels. Real consumption per capita, meanwhile, remains 2.4% below the pre-pandemic equivalent. Household GCF, however, was 48.6% above the 2019 figure, growth that is above the Eurozone average.

The fact that purchasing power per capita is at similar levels to before the health crisis, while consumption volumes per capita remain below that benchmark points to room for considerable growth in household expenditure in the coming years, particularly considering that the rate of unemployment, the key determinant of household savings in Spain due to the precautionary effect, continues to come down, coupled with the fact that household purchasing power is expected to recover further in 2024.

Weak recovery in corporate profits

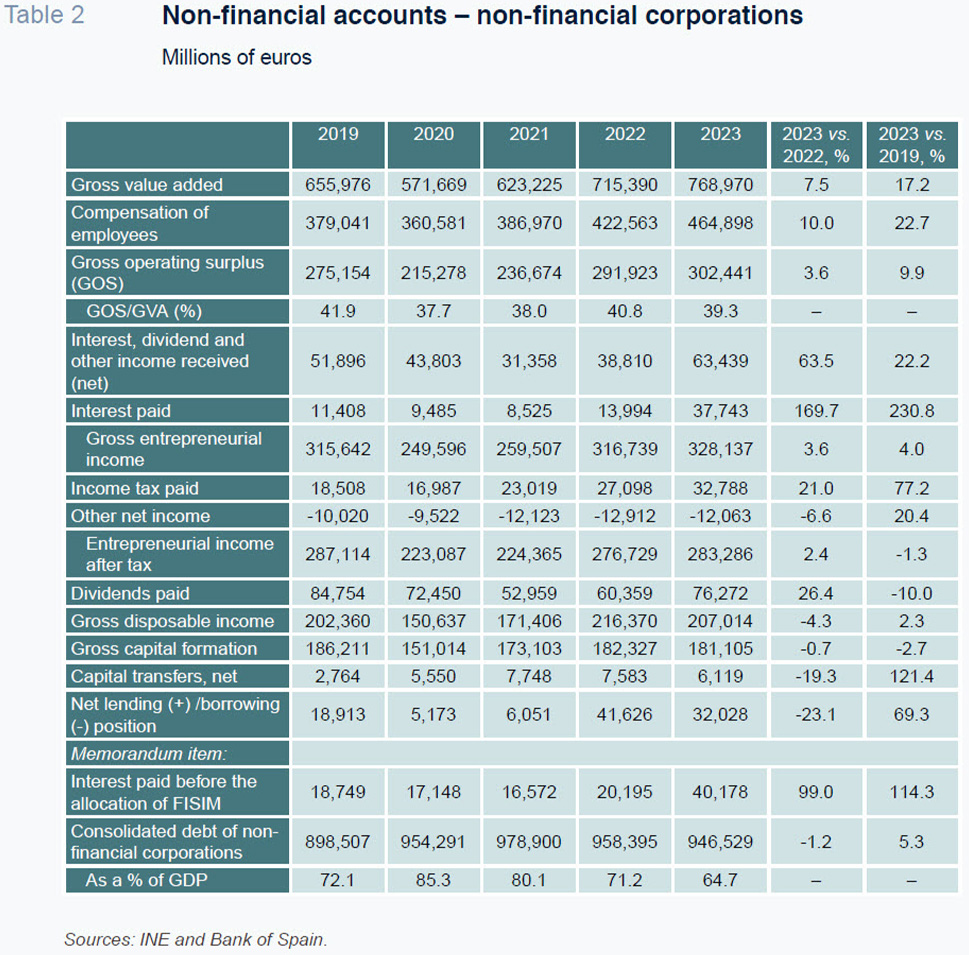

The accounts for the NFC sector for 2022 and previous years have also been revised, in this case by more than the household sector’s accounts. The main difference with respect to the previously published figures lies with the property income received by the NFCs, which was revised substantially lower, giving rise to a considerable downward revision to the corporate income figure – defined as GOS plus interest, dividend and other income less interest paid – such that by 2022 it was practically flat compared to 2019, and not 5% higher, as had been indicated by the original numbers. Moreover, after the payment of tax, corporate income was actually still below pre-pandemic levels. The revisions also had a considerable impact on the volume of dividends paid out, which meant that, despite the changes, corporate GDI – firms’ income after tax and dividend payments – was actually higher than initially estimated. However, the GCF figures were also revised upwards, so that the net lending position barely changed.

Turning to 2023, the growth in corporate income slowed considerably by comparison with 2022 to 3.6%, shaped by slower growth in GOS and higher net interest payments, which increased by 20 billion euros (before the FISIM allocation). The impact of this increase on the corporations’ accounts was greater than in the household sector, as the incremental debt service burden used up a much bigger percentage of the growth in their income before interest.

Tax payments increased by much more than the corporations’ income, leading to a considerable increase in the effective tax rate calculated using the national accounting figures. After tax payments, corporate income increased by 2.4%. Dividend payments increased by much more than the corporations’ bottom lines (albeit remaining below 2018 and 2019 levels) so that their gross disposable income, i.e., their savings after the payment of dividends, decreased by 4.3% (Table 2).

By comparison with 2019, 2023 GOS was 9.9% higher

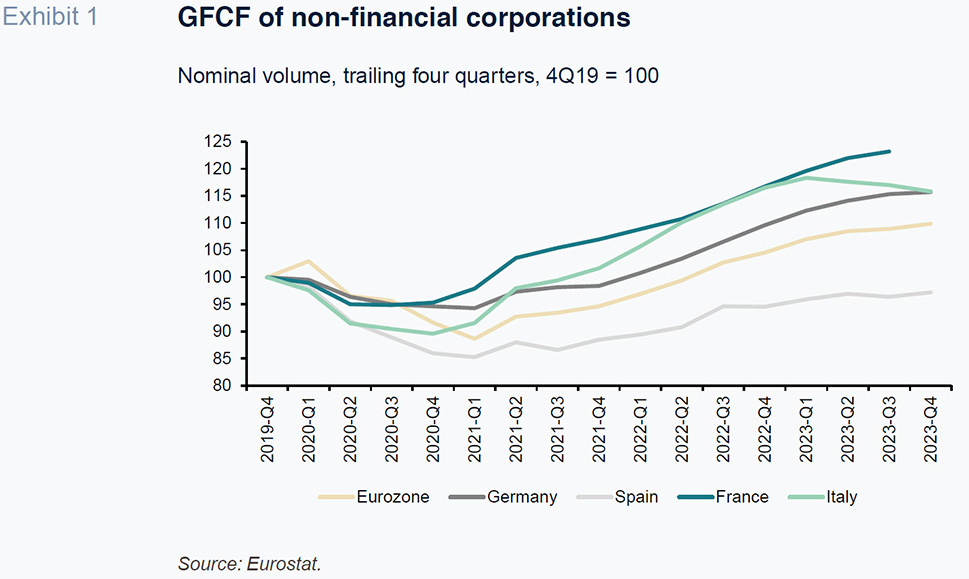

[1] – the lowest rate of growth among the Eurozone countries for which the data is available – whereas corporate income after tax was 1.3% below 2019 levels. This weak earnings performance may be behind the adverse trend in GCF in the NFC sector, which in 2023 was still 2.7% below the 2019 figure in nominal terms. It is the only sector in which investment is still trailing pre-pandemic levels and also the only Eurozone country (for which we have data) other than Ireland where this is the case (Exhibit 1).

There is no specific indicator for deflating GFCF for the NFCs but it can be approximated based on the trend in the deflators for the various components of GFCF for the sectors as a whole. Using that proxy, corporate investment is still over 10% below 2019 levels in real terms. It is also the only institutional sector to have sustained a decrease in real terms, as similar calculations indicate that household, public sector and financial sector investment have all increased since 2019 in real terms.

The corporations used all their financial surplus to repay debt. They even sold off financial assets and used the proceeds to pay down their debt, marking the first time since 2012 that the NFCs sold more financial assets than they bought. As a result, the sector’s debt decreased in nominal terms and in relation to GDP, to 64.7%, the lowest level since 2002 and below the Eurozone average.

Conclusions

Whereas in 2022, corporate income registered significant growth, nearly revisiting pre-pandemic levels, in 2023, it was household income that was more dynamic.

The trend in household income has been relatively favourable throughout the post-pandemic years, despite sharp inflation, thanks, mainly to a strong job market and wage growth. These factors allowed Spain’s households to absorb the impact of the increase in interest rates in 2023 with relative ease. In the corporate sector, however, the increase in rates had a more pronounced impact, although that is not the only reason for its relatively weak earnings performance. Indeed, GOS, a measure of profits before interest payments, registered moderate growth, down significantly from 2022 and below the growth in the compensation and benefits received by the country’s households, which, in contrast, accelerated.

By comparison with 2019, the income gap between the NFC and household sectors widened, revealing an incomplete recovery in the corporate segment (based on the national accounting figures), compared to solid growth in household income (all expressed in nominal terms; Exhibit 2). Lastly, Spain’s corporations have continued to display little appetite for investment, preferring to use their profits to repay debt, despite already healthy leverage levels by both historical standards and by comparison with their European neighbours.

Notes

This result based on the national accounts contrasts with the GOS measure published by the Business Margins Observatory on the basis of the corporations’ tax filings, which points to stronger growth, although there are many differences in the methodologies used to calculate the two sets of statistics.

References

María Jesús Fernández. Senior Economist at Funcas