The 2021 labour market reform: A preliminary assessment

The 2021 labour reform represents a broad social agreement that dissipates some uncertainties over labour relations since the approval of the previous reform in 2012; however, the reform is not sufficiently ambitious to tackle many of the structural problems affecting the Spanish labour market. Preliminary evidence points to some favourable improvement in labour market trends following the reform´s implementation, but the coming years will be key to determining its ultimate success.

Abstract: The long-standing structural problems in Spain´s labour markets have translated into significant inequality and loss of economic efficiency. In efforts to address these issues, the labour reform approved at the end of 2021 represents a broad social agreement that dissipates some uncertainties, at least in the short-term, regarding the framework governing labour relations since the reform of 2012. Indeed, in addition to introducing improvements, such as narrowing the set of available contracts for employers and workers and increasing the focus on training, the reform maintains several of the achievements secured over the last decade, such as those related to dismissals, firm-level flexibility mechanisms (i.e., furlough schemes), and contracting/subcontracting arrangements. However, due to the limitations shaped by sharply-clashing starting positions across the various negotiating parties, the reform is not sufficiently ambitious to tackle the structural problems affecting the Spanish labour market. In calibrating the ‘flexicurity’ trade-off, the reform leans towards security, introducing elements of rigidity and ultimately restricting temporary hiring rather than stimulating open-ended hiring, potentially weighing on employment growth. A few months into the reform, preliminary evidence points to some favourable improvement in labour market trends. However, it is too soon to draw any definitive conclusions. The coming years will be key to determining how the private and public sectors implement the reform and how the legal system interprets these changes.

Introduction

Over the past four decades, approximately half of the gap in income per person of working age in Spain relative to the most advanced European economies has been attributable to labour market inefficiencies and inequities. Between 1980 and 2021, the rate of unemployment in Spain averaged 16.9% (more than double the rate in the aforementioned countries), marking a low of 8.2% in 2007 and a high of 26.1% in 2013, revealing how cyclical employment has been. Given that youth unemployment tends to double that of the overall labour force, it is hardly surprising that Spain fares relatively poorly in the opportunities it creates for its young people. Moreover, the incidence of temporary employment has been among the highest in the EU for decades. All of which has meant that the flows from employment to unemployment and vice versa have been very volatile. In contrast, part-time employment, particularly that which is voluntary, is far less prevalent than in neighbouring countries.

Unemployment in Spain is very high but worse still is the rate of long-term unemployment. The evidence shows that, unlike in other countries, the most common response by the labour market to adverse shocks in demand or supply has been to destroy jobs rather than reduce wages or working hours. The only exception to that pattern in decades was the COVID-19 crisis, when the furlough scheme paved the way for an adjustment via hours worked rather than job destruction. Lastly, it is worth highlighting the existence of significant regional disparity, marked by huge differences in unemployment rates that are adversely correlated with regional labour productivity levels.

All of these problems translate into significant inequality as unemployment and temporary work is concentrated more heavily in more vulnerable, lower-income population groups. As shown later on, the evidence shows that unemployment has been responsible for 80% of the change in inequality in Spain over the last three decades. Furthermore, these labour market weaknesses imply an important loss of economic efficiency. Firstly, because a large percentage of working-age people are not working. Secondly, because employment instability affects the stock of human capital by interrupting the accumulation of skills and work experience. In sum, the anomalous manner in which the job market functions in Spain has a huge cost in terms of social wellbeing.

Since the Spanish labour market’s deficiencies are structural and well documented, the European Commission has been making specific recommendations for their resolution for years now. The rollout in 2020 of the NGEU recovery fund in response to the COVID-19 economic crisis requires the countries receiving those funds to take corrective action in order to adopt those country-specific recommendations. As a result, component #23 of Spain’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan encompasses a raft of measures designed to make the labour market function more efficiently, specifically including the labour reform approved at the end of 2021.

The economic policy behind the 2021 labour reform

To understand the economic policy behind the 2021 reform, it is important to understand the social partners’ starting positions. That of the employer and business associations was to preserve, to the extent possible, the aspects of the 2012 reform that rendered the labour market more flexible and prevent any backtracking towards more rigid labour relations. Unfortunately, the key aim of the unions, part of the government and some of the other political parties was to repeal the 2012 reforms and some of those pushed through in 2010, without having rigorously analysed their effects or reached a consensus with respect to the structural problems afflicting Spain’s labour market, such as those pointed out by the Strategic Foresight Office (2021) and Andrés and Doménech (2015). The problem is that if the reforms are articulated around a biased or potentially misguided diagnosis, it is unlikely they will resolve the structural problems undermining the labour market.

Criticism of the labour reforms of 2010 and, above all, 2012 has centred on the precarious nature of employment, the decline in real earnings and, as a result of the first two phenomena, the increase in inequality. The evidence, in contrast, suggests that during the recovery staged in the wake of the Great Recession and the sovereign debt crisis, until the onset of the pandemic, the labour market fared better on all three counts than during the previous growth cycle, from 1994 to 2007.

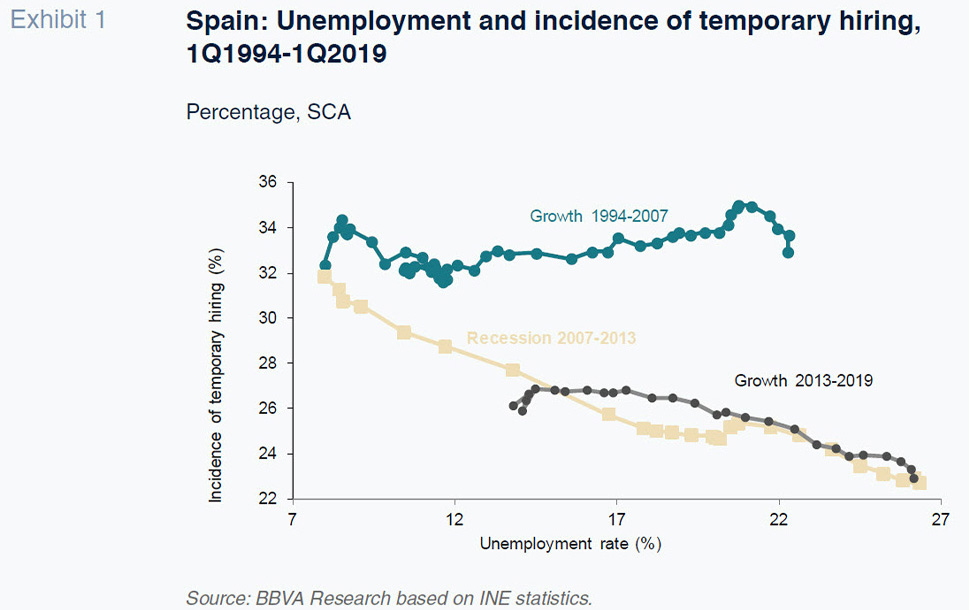

Exhibit 1 provides the incidence of temporary work from the first quarter of 1994 until the last quarter of 2019, relative to the unemployment rate. The average between 1994 and 2007 was 33.1%. In contrast, the average between 2013 and 2019 was 25.4%, nearly eight points lower. At the end of 2019 when unemployment stood at 13.8%, the incidence of temporary work was 26.1%, compared to 32.8% when unemployment was at that same level during the previous growth cycle. The reforms of 2010 and 2012 reduced the gap in the cost of laying off workers on open-ended contacts and set objective criteria for such layoffs (OECD, 2013), unquestionably helping reduce the incidence of temporary work, as did the shift in the economy’s sectoral make-up (for example, reduced weight of construction) and in the pattern of growth (for example, growth in exports and exporting firms, which tend to hire relatively fewer temporary workers).

It is worth noting, however, that the changes in the sectoral structure do not appear to be sufficient to explain the significant reduction in the use of temporary hiring arrangements between the two growth cycles. In fact, if we decompose the reduction between that prompted by the changes in sector weightings and that attributed to other factors, we observe the existence of a component that is common across all sectors. Despite enormous differences in the incidence of temporary hiring from one sector to another (54% in the primary sector versus just 8% in the financial sector), the movements in the weight of the various industries explain a scant few tenths of a point of the reduction in incidence. The reason is that, with the exception of the education, health and government sectors, the incidence of temporary work has fallen across the board. Between 1995 and 2020, it decreased by 6.7 points in the primary sector, 7.3 points in services, 13.5 points in manufacturing and 27.8 in construction.

Another common criticism of the earlier reforms is the fact that the average duration of temporary contracts has shortened, increasing contract turnover. However, even though the previous reforms increased incentives for open-ended relative to temporary contracts, none of the reforms altered the relative attractiveness of one kind of temporary arrangement over another. Therefore, the reason for the growth in turnover as the prevalence of temporary hiring came down must lie elsewhere, with technological transformation and digital disruption potentially responsible for the greater use of shorter-duration contacts.

A complementary aspect of job precariousness is the rate of part-time employment, especially that which is involuntary. However, here too we find no major changes with respect to the previous situation. According to Eurostat data as of 2019, the rate of part-time employment in Spain was 14.4% that year, seven points below the EU average and similar to the level observed in the years prior to the Great Recession. Moreover, the percentage of involuntary part-time work (53% in 2021) is very similar to that observed, for example, in 2011 (54%). If, in addition to these aspects, we consider the incidence of low-paid work, overqualified work and the nature of working hours (for example, the study compiled by the union Comisiones Obreras and the International Economics Institute at Alicante University, 2021), we conclude that precariousness was similar or less prevalent in 2019 than in the years before the Great Recession.

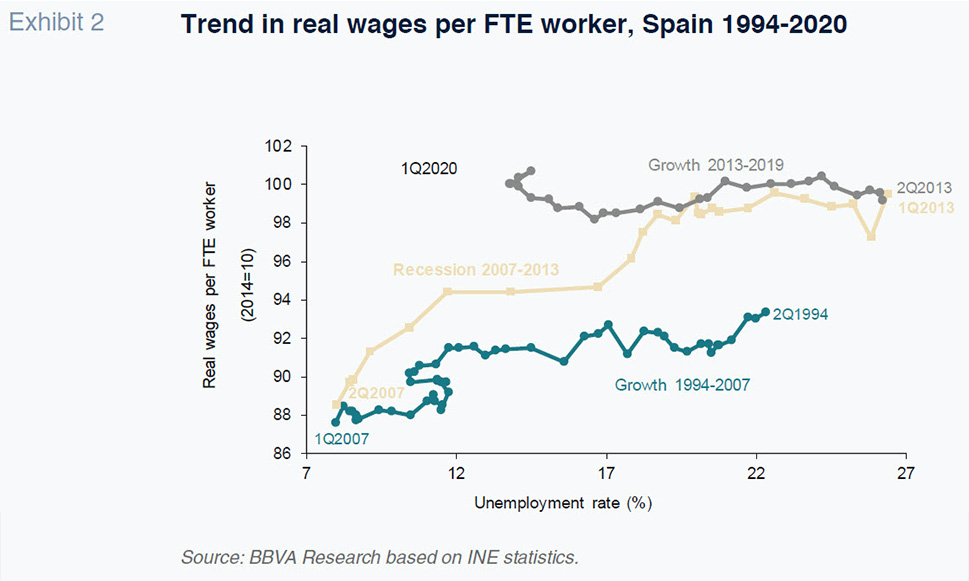

The precariousness allegedly introduced by the reform of 2012 has also been interpreted through the prism of wage devaluation, i.e., a reduction in real earnings. Nor, however, does the evidence corroborate that critique. Exhibit 2 depicts the trend in real average earnings per full-time equivalent employee using the GDP deflator to convert the nominal figures into real ones, relative to the rate of unemployment. That analysis shows how the trend in real wages during the years of growth between 2013 and 2019 was better than that observed during the previous cycle, between 1994 and 2007. The recovery initiated in 2013 ushered in a reduction in unemployment in tandem with stability in average real earnings. From the start of the recovery in early 2013 until the first quarter of 2020, unemployment came down by 12.6 points, from 26.4% to 13.8%. During that period, real wages increased by 0.1%, i.e., virtually stable, for every one-point reduction in unemployment. The negative composition effect of the changes in employment on real wages that characterised previous growth cycles and recessions was not repeated during those years. In contrast, between 1994 and 2007 both unemployment and average real wages trended lower. During the previous expansionary phase, from the second quarter of 1994 until the first quarter of 2007, the rate of unemployment came down 14.3 points (from 22.3% to 8%), but real average wages decreased by 6.1%. That implied a reduction in real wages of 0.43 percentage points for every one-point reduction in the unemployment rate.

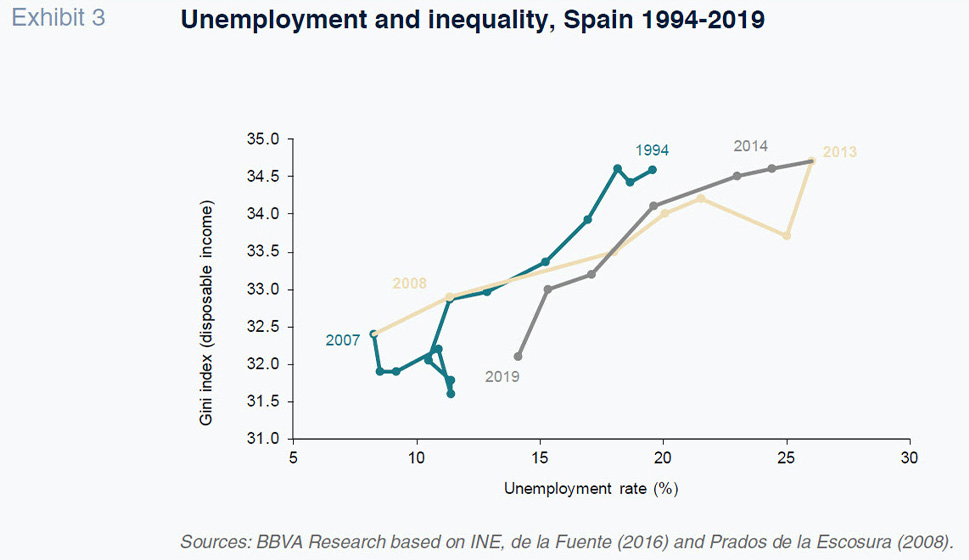

Lastly, the third common criticism of the 2012 reform is that, as a result of the precarious nature of the job market, inequality has increased. Exhibit 3 depicts the trend in inequality, measured using disposable income after taxes and transfers, between 1994 and 2019. The first observation is that inequality is closely correlated with unemployment: the coefficient is 0.87, so confirming that the best strategy for reducing inequality in Spain is to increase the rate of employment. The second observation is that in the growth cycle initiated in 2013, inequality was nearly one point lower than in 1994-2007 at the same level of unemployment. In fact, in 2019, the Gini index was at a similar level as it was in 2005 and 2006, and actually lower than it was 2007, even though unemployment was around six points higher.

The evidence presented in Exhibits 1 to 3 shows that it is not accurate to attribute the precariousness prevailing in the job market or the structural problems it has been carrying on its shoulders for years to the reforms of 2010 and 2012.

The assessment of the 2012 reform by Doménech, García and Ulloa (2018) concludes that it prevented greater job destruction in the wake of the sovereign debt crisis over the course of 2012, and that, if the reform had been in place in 2008, it could have prevented a roughly eight-point increase in the unemployment rate between 2009 and 2012. In addition, it is fair to say that the reform of 2012 paved the way for a rapid reduction in unemployment without accumulating the macroeconomic imbalances that led to the crisis of 2008, all of which accompanied by a better performance in temporary hiring, real wages and inequality relative to the previous wave of growth, from 1994 to 2007. That being said, it is important to note that it is very hard to isolate the effects of the labour market reforms from other factors taking place during the same period. Even using methods to pinpoint which structural factors are behind the trend in variables such as employment and real wages, it is hard to separate the effects of the reform of 2012 from other factors, such as the Employment and Collective Bargaining Agreement hammered out that same year. What this sort of structural assessment does tell us is that the labour market worked more efficiently and contributed to higher growth and a more balanced recovery (refer, for example, to Boscá et al., 2021). Complementing that conclusion, Stepanyan and Salas (2020) conclude that the labour reform of 2012 helped bolster job creation and the equitable distribution of household income without a significant impact on the risks of encountering poverty.

Contents of the 2021 reform

Royal Decree-Law 32/2021, of December 28th, 2021, on urgent measures to reform and transform the labour market and guarantee job stability, reflects the agreement reached between the social partners and the government to deliver some of the milestones promised to the European Commission as a prerequisite for disbursement of the NGEU funds.

In light of the analysis provided in the last section, it is certainly good news that an agreement was reached that includes unions, employer associations and the government, helping create social harmony and reducing uncertainty in the labour market, all the more so in light of the tremendous uncertainty implied by the post-pandemic recovery and, in recent weeks, that created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In recent years, the proposals made by the unions and certain political parties to repeal the changes introduced by the reform of 2012 and amend labour regulations has been a source of uncertainty for the productive sector which, with this latest reform, has, fortunately and for the most part, dissipated.

It is also good news that the 2021 reform respects many of the changes introduced in 2010 and 2012. The costs of dismissing people on open-ended contracts and, by extension, the gap with respect to the cost of terminating temporary contracts, have been left intact. The latest reform has not made any changes to the objective rules for proceeding with dismissals. Businesses can still opt out of higher-level collective bargaining agreements. Other measures left in place include the furlough scheme, the option of reducing working hours and employers’ unilateral ability to make substantial changes to employment terms for economic, technological, organisational or productive reasons. The experience gained from the sovereign debt and COVID-19 crises is that firm-level flexibility mechanisms such as these have been crucial in reducing job destruction rates (refer, for example, to the evidence provided by Boscá et al. [2017], on the separation rate since 2012).

The new reform narrows the suite of contracts, essentially boiling the choice available to employers and workers down to three contract types: open-ended (the default option), temporary (for specific reasons) and training. Within open-ended contracts, the so-called “fixed-discontinuous” contract has been made more flexible. Works contracts automatically become open-ended contracts; however, the end of the works that originate the initial hire constitutes objective grounds for terminating the contract. It would have been a positive development if that criterion had been applied more generally to other types or activities and sectors as it would have helped pin down the objective grounds for dismissal and reduce the legal uncertainty felt by businesses regarding the termination of open-ended contracts, further eating into the incidence of temporary hiring.

The approved reform leaves contracting and subcontracting arrangements intact, clarifying that multi-service firms need to apply sectoral collective agreements in each of the professions and services they offer. The reform opted for an intermediate solution which, on the one hand, restricts competition between companies susceptible to competing by leveraging their own collective agreements to offer lower prices and, on the other, stops short of banning business outsourcing and subcontracting, which would have been an extremely inefficient measure in economic terms and would have been tantamount to an assault on companies’ right to freely organise their productive processes.

Another positive development is the importance attached to the dual vocational training scheme and training contracts. For that strategic play to work out, the training programmes will need to be well designed and satisfy the specific emerging needs of the productive system. For those contracts to boost youth employment, it would be a good idea to assess to what extent having to pay the minimum wage to young people with no prior work experience who are joining the job market is a limitation in certain sectors, positions, regions and companies, particularly SMEs. In other European countries, the minimum wage for youths with no prior work experience is lower than that for other works for a limited time. The difference between the two could be covered, at least partially, by a public wage supplement.

As for the firm-level flexibility mechanisms, the labour reform commits to the furlough scheme (a mechanism in use for decades, which made it possible to keep millions of people in work during the pandemic thanks to its combination of wage supplements and rebates from the state) and introduces a new employment flexibility and stabilisation mechanism (RED, which means net in Spanish), which has yet to be implemented.

With a few caveats, the aspects itemised so far constitute advances for Spain’s labour relations, and fall on the plus side of the column, alongside the aspects of the 2012 reform left intact. However, it is not all good news. The 2021 reform is not sufficiently ambitious to tackle the structural problems afflicting the labour market. In calibrating the ‘flexicurity’ trade-off, the reform leans towards security in open-ended hiring and also in temporary hiring by means of longer-duration contracts, introducing elements of rigidity as a result. For example, unlike the 2012 reform, this round of reforms has opted above all to toughen temporary hiring terms and conditions. In addition to introducing the notion that all contracts will be presumed open-ended, the reform narrows the criteria for making temporary hires, establishes limits on how long temporary contracts can be used and penalises their successive rollover. What the reform does, therefore, is to restrict temporary hiring rather than stimulate open-ended hiring, for example by accounting for severance entitlements at the individual worker level to ensure their portability between jobs, reducing the gap in those termination benefits between temporary and open-ended contracts (or changing their sign) or increasing legal certainty around indefinite hiring.

Another rigidity introduced is the reinstatement of the primacy of higher-level collective agreements over firm-level agreements for wage-setting purposes. Although this change only affects 8% of all workers, most studies (for example, OECD, 2019) find evidence in favour of providing the flexibility needed to align wages with business productivity. It is worth recalling that in Spain the collective bargaining agreements negotiated at the firm level reveal a wage premium with respect to higher-level agreements beyond that attributable to the characteristics of the companies and workers in question. As for the return to indefinite ultra-activity, most collective bargaining agreements already contained negotiated clauses to avoid the one-year limit on ultra-activity introduced by the 2012 reform.

Initial effects of the labour reform

The reform´s ability to reduce the incidence of temporary hiring in Spain will depend largely on whether the hiring that has traditionally taken the temporary route will be redirected to the –more stable– fixed-discontinuous contract where the employer-worker relationship is not severed, and which is propitious to accumulating experience and preventing the loss of productivity. A few months into the reform, the preliminary evidence looks positive, although it is too soon to draw conclusions, for which it is necessary to verify whether the initial trends consolidate over time. The trend in open-ended contracts is positive and that is a good sign. Conversions to open-ended contracts approached the 100,000 mark in February 2022, compared to an average of around 60,000 in prior years. New open-ended contracts increased by a factor of 2.2 to around 225,000, compared to an average of around 100,000 prior to the reform. Elsewhere, the number of fixed-discontinuous contracts increased to close to 70,000 in February 2022, compared to an average of around 20,000 in previous years.

As a result of that increase in open-ended hiring, the incidence of temporary arrangements in new hires has decreased from a monthly average of 90% before the reform to 77%. It remains to be seen, when the next labour force survey is released, how these changes in hiring flows are affecting the overall incidence of temporary work relative to total wage-earners. It will also be important to evaluate what portion of the reduction we are seeing in temporary hiring is driven by conversions to fixed-discontinuous contracts of works contracts in the construction sector that used to be classified as temporary and are now considered open-ended, as opposed to a more widespread decrease in temporary hiring.

The figures also reveal a reduction in the number of contracts with a duration of less than one month, which accounted for 40% of all temporary contracts in 2021. The surcharge of 26 euros per short-duration contract makes it more expensive to use, a measure that should serve to stretch out the average duration of temporary contracts, which in 2021 barely topped 53 days. It is conceivable that the reduction we are seeing in short-duration contracts is attributable to that penalty. However, a similar decrease was also observed during the final months of 2021, as a result of more intense Social Security inspection activity in this area. Without a doubt, contract duration, and not just temporary versus open-ended hiring, is one of the metrics to watch closely.

In addition to monitoring the trend in hiring arrangements and contract duration and ensuring compliance with the new regulations, the authorities need to ensure that the drop in temporary hiring does not come at the cost of slower growth in employment. For now, growth in Social Security contributors amounted to 0.3% in February 2022, a scant 0.1 of a percentage point below the average for the previous decade.

Conclusions

The labour reform approved at the end of 2021 represents a broad social agreement that dissipates some uncertainties, at least in the short-term, regarding the framework governing labour relations since the reform of 2012. In addition to introducing improvements, the reform does not reverse important achievements etched out over the last decade. However, due to economic policy restrictions shaped by sharply-clashing starting positions, the reform is not sufficiently ambitious to tackle the structural problems affecting the Spanish labour market by moving towards greater “flexicurity”, as seen in central and northern Europe. Although the reform will foreseeably reduce temporary hiring in the private sector as temporary contracts have been made more onerous, open-ended contracts have not been rendered more flexible. Given that legal uncertainty and the cost of terminating open-ended contracts (both ordinary and fixed-discontinuous) remain higher relative to temporary contracts, it is possible that a portion of the targeted or expected conversions will not take place, weighing on growth in employment.The coming years will be key to seeing how the private and public sectors implement the reform and how the legal system interprets these changes.

References

ANDRÉS, J. and DOMÉNECH, R. (2015).

En busca de la prosperidad. Los retos de la sociedad española en la economía global del siglo XXI [In search of prosperity. The challenges facing Spanish society in the global economy of the 21

st century]. Deusto Planeta de Libros.

http://bit.ly/3hYHTZFBOSCÁ, J. E., DOMÉNECH, R., FERRI, J. and GARCÍA, J. R. (2017). Shifts in the Beveridge Curve in Spain and their macroeconomic effects.

Revista de Economía Aplicada, 25(75), pp. 5-27.

http://bit.ly/3vZk5gKBOSCÁ, J. E., DOMÉNECH, R., FERRI, J. and ULLOA, C. (2021).

Factors explaining the economic cycle a year on from the Great Lockdown. BBVA Research.

http://bit.ly/3J6TZvUCC.OO. and IEI UNIVERSITY OF ALICANTE (2021).

La precariedad laboral en España Una doble perspectiva [Job precariousness in Spain. A dual perspective].

http://bit.ly/3tPfcE3DOMÉNECH, R., GARCÍA, J. R. and ULLOA, C. (2018). The effects of wage flexibility on activity and employment in Spain.

Journal of Policy Modeling, Volume 40(6), pp. 1200-1220.

http://bit.ly/3KEh9tENATIONAL FORESIGHT OFFICE (2021).

España 2050. Fundamentos y propuestas para una Estrategia Nacional de Largo Plazo [Spain 2050. A National Long-Term Strategy: Fundamentals and Proposals].

http://bit.ly/3MBXL2xOECD (2013).

The 2012 Labour market reform in Spain: A preliminary assessment. http://bit.ly/3t1QrVYOECD (2019).

Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work. Paris: OECD Publishing.

http://bit.ly/3t5x52wSTEPANYAN, A. and SALAS, J. (2020).

Distributional Implications of Labor Market Reforms: Learning from Spain’s Experience. International Monetary Fund.

http://bit.ly/3J5ms5f

Rafael Doménech. BBVA Research and University of Valencia