EMU peripheral sovereign debt: Resilience in the face of monetary policy and geopolitical risks

Looming ECB policy normalisation will likely lead to the rebalancing of relative prices for EMU peripheral sovereign debt. Nonetheless, improved economic fundamentals, the ECB’s commitment to preventing fresh episodes of financial fragmentation and favourable prospects for European integration should help reduce the risk of episodes of intense stress in the eurozone sovereign debt markets.

Abstract: The potential withdrawal of monetary stimulus measures marks a very significant milestone for the price of public debt issued by peripheral eurozone member states. The ECB has been the biggest investor in peripheral sovereign bonds in recent years, acting as a price-taker with the unwavering objective of preventing episodes of financial fragmentation that hinder the correct transmission of monetary policy and increase the risk of financial instability. The heightened probability of accelerated withdrawal of the ECB´s monetary stimulus will likely be accompanied by the rebalancing of the relative prices of EMU peripheral sovereign debt. Indeed, the main consequence of the anticipated ECB policy shift –albeit subject to significant uncertainty related to the degree of economic fallout from the escalation of geopolitical tensions– is that the market needs to define a new equilibrium price for Spanish and Italian debt relative to that of Germany. Nonetheless, the improvement in those economies’ structural health, the ECB’s commitment to preventing fresh episodes of financial fragmentation and the outlook for strong progress towards European integration should help to reduce the risk of episodes of intense stress in the eurozone sovereign debt markets.

Introduction

During the last two years, we have witnessed two episodes of stress in eurozone peripheral sovereign bond spreads.[1] The first took place in conjunction with the health crisis induced by COVID-19 starting towards the end of February 2020. The second episode, which began at the end of the summer of 2021, and is largely attributable to expectations that monetary stimulus measures will be rolled back, above all, but also the reintroduction of the EU fiscal rules, remains ongoing. Matters have just been complicated considerably by the war in Ukraine, the consequences of which are still highly unpredictable. During this second episode, the magnitude of the widening in spreads has –so far– been mild by comparison with that of the spring of 2020 but is nonetheless considerable.

Our study of both periods starts from an analysis of the fundamental factors that generated the tension in peripheral bond spreads and the monetary and fiscal policy measures that helped mitigate that tension. Then, to identify the type of underlying risk behind the spread widening in each episode, we take stock of other market variables that provide additional insight. Lastly, the ongoing geopolitical tensions from the war in Ukraine prompt us to look forward, with all due caution, at where the factors that could shape peripheral bonds spreads could be headed.

Dimensions of the risk premium and its interpretation

The difference in yields on sovereign bonds in the eurozone periphery and Germany is the measure most widely used to track the credit risk premium of the former. However, this measure can –and we think should– be rounded out with an analysis of other market variables to enrich our analysis of how the market is interpreting that risk at any given point in time and to help identify the nature of the factors the market associates with changes in the perceived ability of one country to repay its debt relative to that of another more creditworthy nation.

The key to the analysis is to identify to what extent the movement in country risk premiums is attributable to expectations regarding the direction of monetary policy; a shift in the equilibrium between market supply and demand vis-à-vis the advent or withdrawal of key players (with the central banks playing a leading role); sudden shifts in general risk aversion related with changes in the macro-financial environment; the potential impact of a widespread reduction in market liquidity on less ‘liquid’ markets; or, the emergence of idiosyncratic risks associated with the political or economic situation of a specific country or group of countries.

Our analysis will factor in two variables –in addition to standard 10-year yield spreads– aimed at capturing the intensity of the idiosyncratic nature of the movements in spreads:

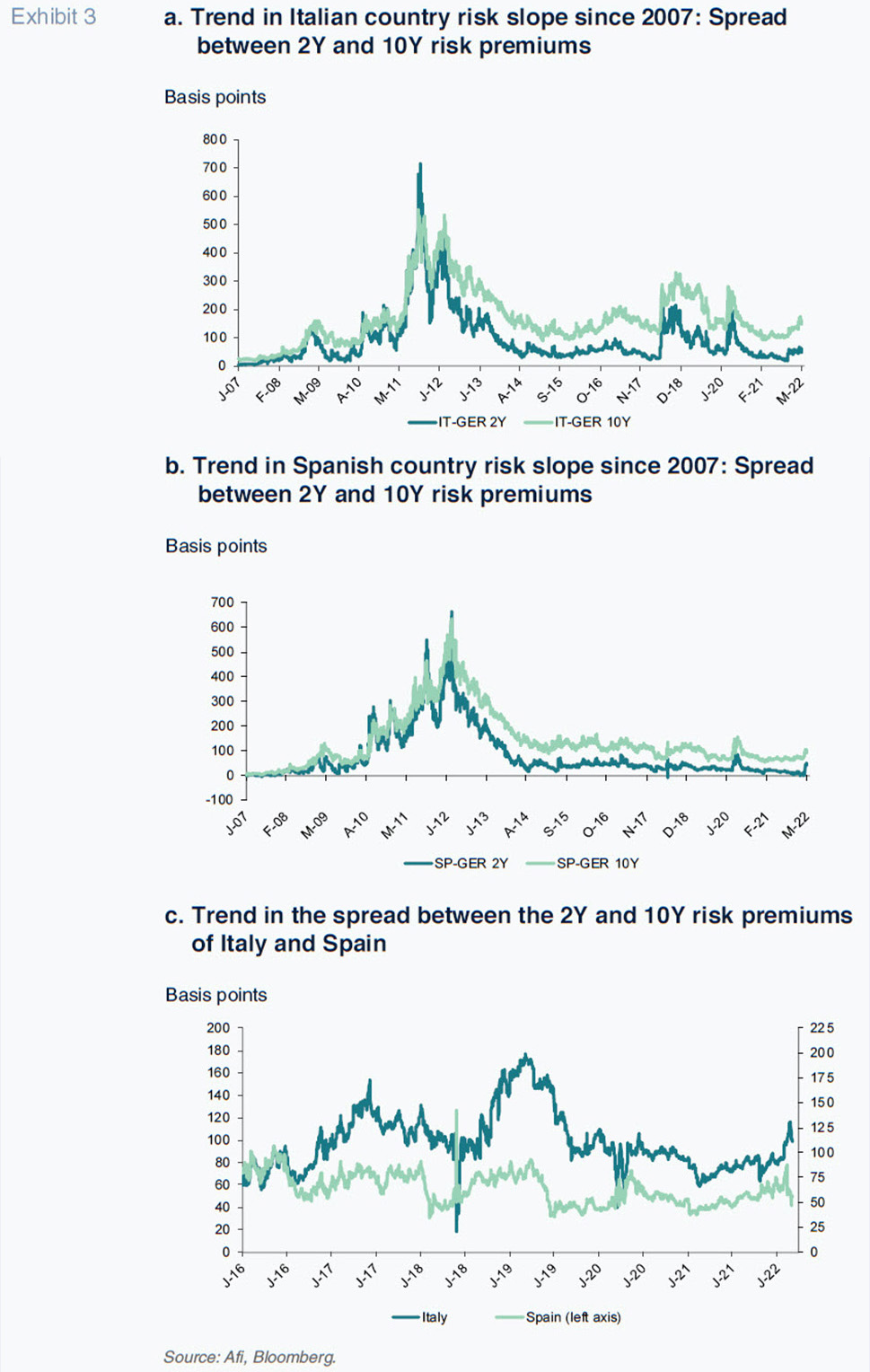

- The term structure of risk premiums, captured by means of the difference between the 2-year and 10-year risk premiums. At times of low and medium sovereign risk stress, the slope between short- and long-term risk premiums is sharp and relatively stable. In contrast, as shown by observation of the trend in that slope, during episodes of sharp growth in idiosyncratic risk, such as the sovereign debt crisis of 2011-2012, the political uncertainty affecting Italy in the spring of 2018 and the first few weeks after the onset of COVID-19 – that slope flattens out substantially.

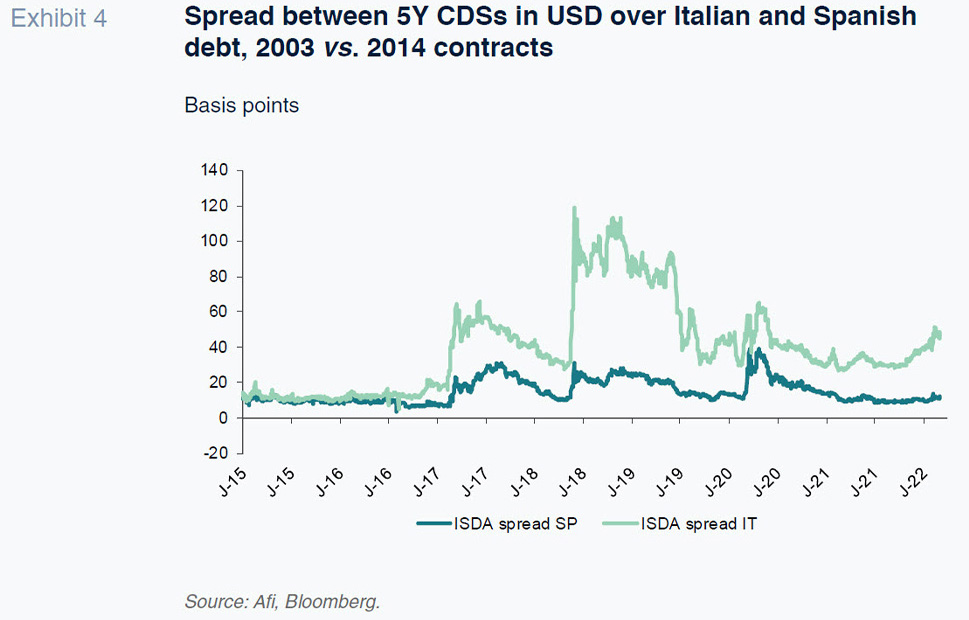

- The difference between the price of ISDA [2] 2014 and 2003 credit default swaps (CDSs) in US dollars over peripheral issuer debt. This measure is key to capturing the quintessential idiosyncratic risk specific to the eurozone debt markets, i.e., that of redenomination of the sovereign debt of a eurozone country into another currency. Given that the 2003 contract does not provide effective protection against that potential credit event while the 2014 contract does, the difference between the price of the two contracts is a proxy for the intensity of that risk. A glance at Exhibit 4 shows how, in the case of Italian debt, the 2018 political crisis drove a substantial increase in that country’s redenomination risk premium.

We could also look at a third variable designed to capture the impact of a reduction in general market liquidity [3] on peripheral versus German yield spreads. Peripheral risk premiums tend to widen due to those securities’ reduced liquidity relative to German debt, without that widening necessarily reflecting an impairment of underlying credit risk. While acknowledging its existence, we do not deem it necessary for our analysis due to its reduced role in the formation of risk premiums by comparison with the other factors considered.

Having defined these variables, we now analyse the recent episodes of Spanish and Italian country risk premium widening with the aim of pinpointing what role each factor played in that widening.

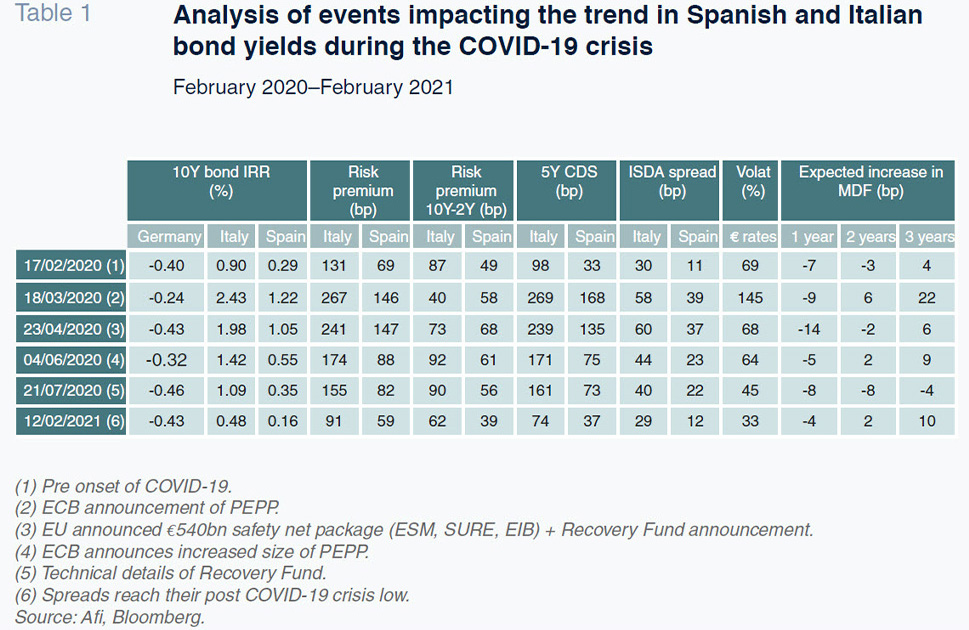

Onset of COVID-19 and response by the European authorities

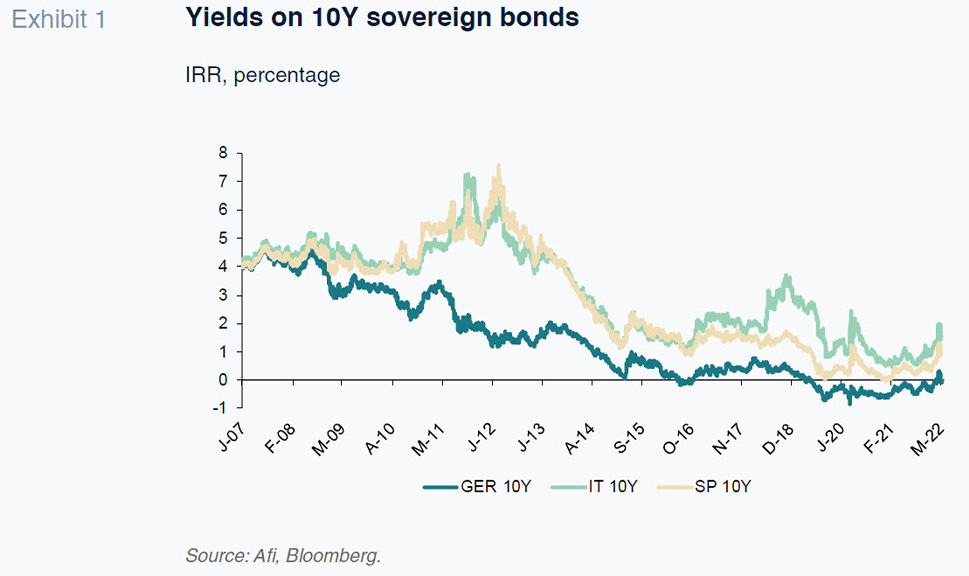

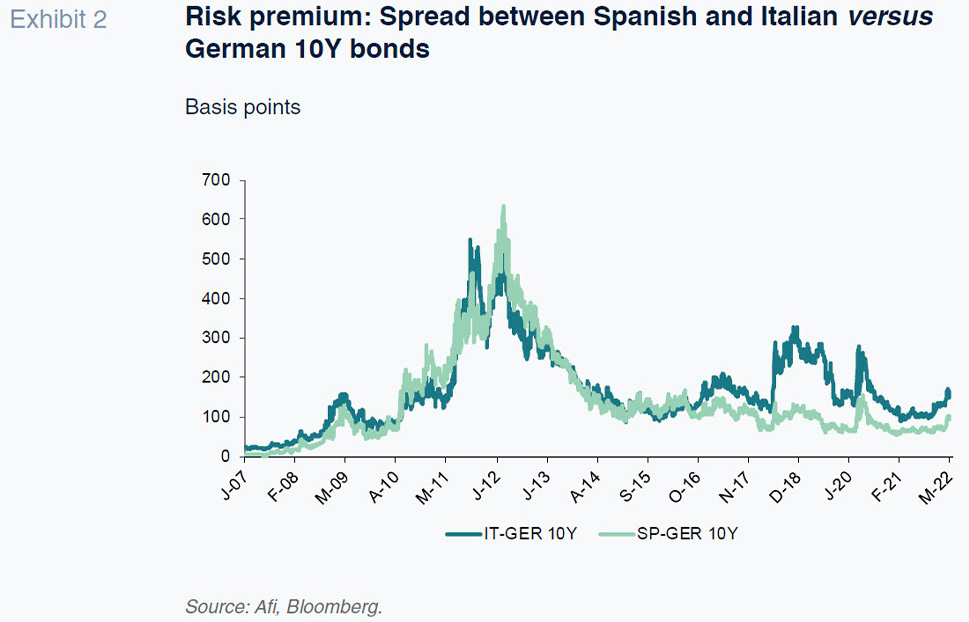

The onset of the crisis induced by COVID-19 in early 2020 triggered a bout –short but intense– of stress for the debt spreads of the governments of the countries dubbed as the eurozone “periphery” (Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece). The cause of the increase in the relative risk of those countries’ debt is well known and lies with the perceived asymmetric impact of a growth shock on countries with very different economic and fiscal positions. From levels of around 70 and 130 basis points for the 10-year spreads between Spanish and Italian bonds over German yields, respectively, the market moved swiftly to levels of 145 and 265 basis points by mid-March.

The rapid and considerable widening in yield spreads took place in parallel with an increase (of a similar magnitude to the increase in debt market spreads) in the price of 5-year CDS coverage, similarly higher for Italy than Spain. The movement in the slope between 2-year and 10-year spreads, particularly in Italy, and the increase in the spread between CDS contracts, or the ISDA spread, likewise more pronounced in Italy, indicate that the idiosyncratic risk component played a significant role in both countries, albeit more significant in Italy. The message sent by the market was clear: the looming shock induced by the health crisis would have an idiosyncratic impact on more vulnerable economies.

The rapid monetary response, first of all, and, at a later stage, the attendant economic policy response, limited the magnitude and scope of that movement, with spreads narrowing quickly once again and the risk premium slope returning to similar, or slightly higher than pre-crisis levels, by the early summer. The reduction in CDS and ISDA spreads was slower and more gradual and it took until early 2021 for them to revisit pre-COVID levels. The reason for the different speeds with which the variables analysed readjusted may have had to do with the differential impact on the bond market (a physical market with finite supply) relative to the CDS market (a synthetic market with theoretically infinite supply) of the ECB’s massive bond buyback announcement.

The monetary policy initiatives that helped rectify the situation included the decisions taken by the ECB’s Governing Council on March 18th, 2020, to create the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) [4] and, later, on July 4th, 2020, to increase that fund in size, from 600 billion euros to 1.35 trillion. The key reason these measures were effective at compressing peripheral spreads lies, in our opinion, with the flexible nature of this buyback programme under which the ECB could repurchase debt in any jurisdiction (or national market), in any structure, and for as long as was necessary. Under the PEPP, the ECB’s debt repurchases can deviate from the ceiling set by the capital key that governs the rest of the buyback programmes created by it, so reinforcing the signal sent to the market that the instrument was a genuine neutraliser of any issues potentially encountered by any eurozone sovereign in accessing the bond markets.

Complementing that monetary policy thrust, the national governments of the EU approved a raft of decisive countercyclical fiscal stimulus measures financed by debt issued by the European institutions. Key developments included the announcement on April 23rd, 2020, [5] of: (i) a safety net package of 540 billion euros to finance the negative impact on EU workers (SURE programme), lend support to businesses by means of loan guarantees channelled by the European Investment Bank (EIB) and a liquidity facility channelled by the ESM to the national governments; and, (ii) the creation of a very sizeable (as yet undefined) recovery fund –which would take the form of the Next Generation EU or NGEU funds– to make a fundamental contribution to the reconstruction of Europe’s economies. That fund –ultimately sized at 750 billion euros– was approved on July 21st, 2020. The message sent by these measures was similarly clear: substantial –and unprecedented for the EU– reinforcement of common fiscal policy structured so as not to harm the public finances of the individual member states.

In short, the combination of ultra-lax and unfettered monetary policy –in the form of the PEPP– in support of the countries most vulnerable to economic deterioration, coupled with a forceful fiscal policy thrust, financed at the EU level so as to have a very limited impact on individual states’ public finances, sent a very powerful message that made a big difference in minimising the perceived risk of fiscal deterioration in the countries most exposed to a negative shock that, while common to all, was destined to have an asymmetric impact at the national level.

Summer 2021 to the present: Expected rollback of unconventional monetary policy and negative shock derived from the war in Ukraine

The second episode of stress in peripheral debt spreads, which remains ongoing, began at the end of the summer of 2021, spurred by the impact that the consolidating recovery post-COVID-19 and, above all, persistently high inflation readings had on market expectations regarding the scale –more pronounced– and timing –sooner– of the withdrawal of monetary stimulus measures by the central banks.

In parallel with the economic recovery and surge in inflation, the market began to price in the renewal, albeit less exacting than was the case until 2019 –of policy pressure in the EU to address fiscal imbalances in the eurozone and reinstate the fiscal rules [6] suspended since February 2020.

The current geopolitical situation, the consequences of which remain highly uncertain, runs the risk of seriously exacerbating the trend in inflation during the next 12 months, while weighing on economic growth, complicating the monetary policy response and raising the fear of a fresh episode of asymmetric fallout throughout the eurozone. By the same token, partially mitigating the above, the uncertainty introduced by the current scenario could well temper the monetary authorities’ decision-making when it comes to withdrawing their stimulus measures, while helping reinforce unity at the European Union level and the institutional architecture around which the eurozone is articulated.

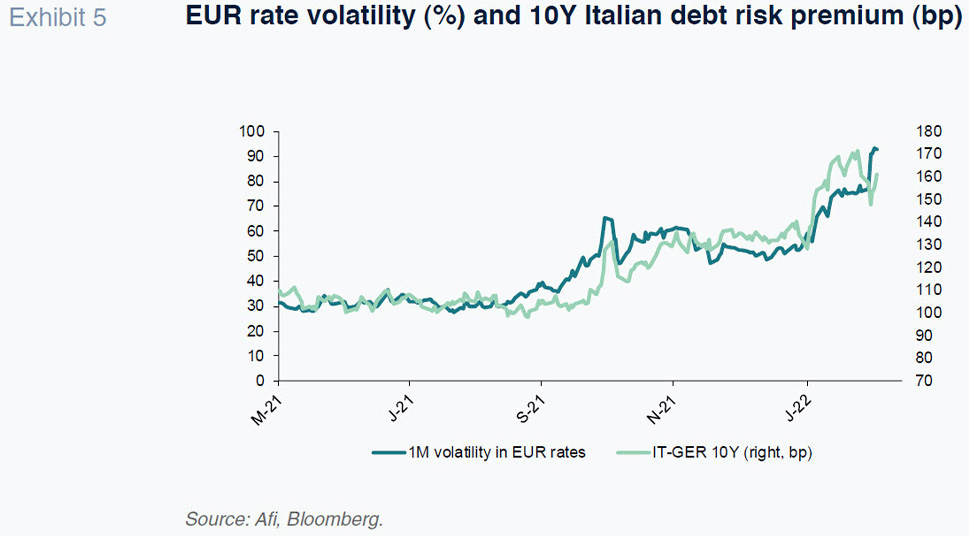

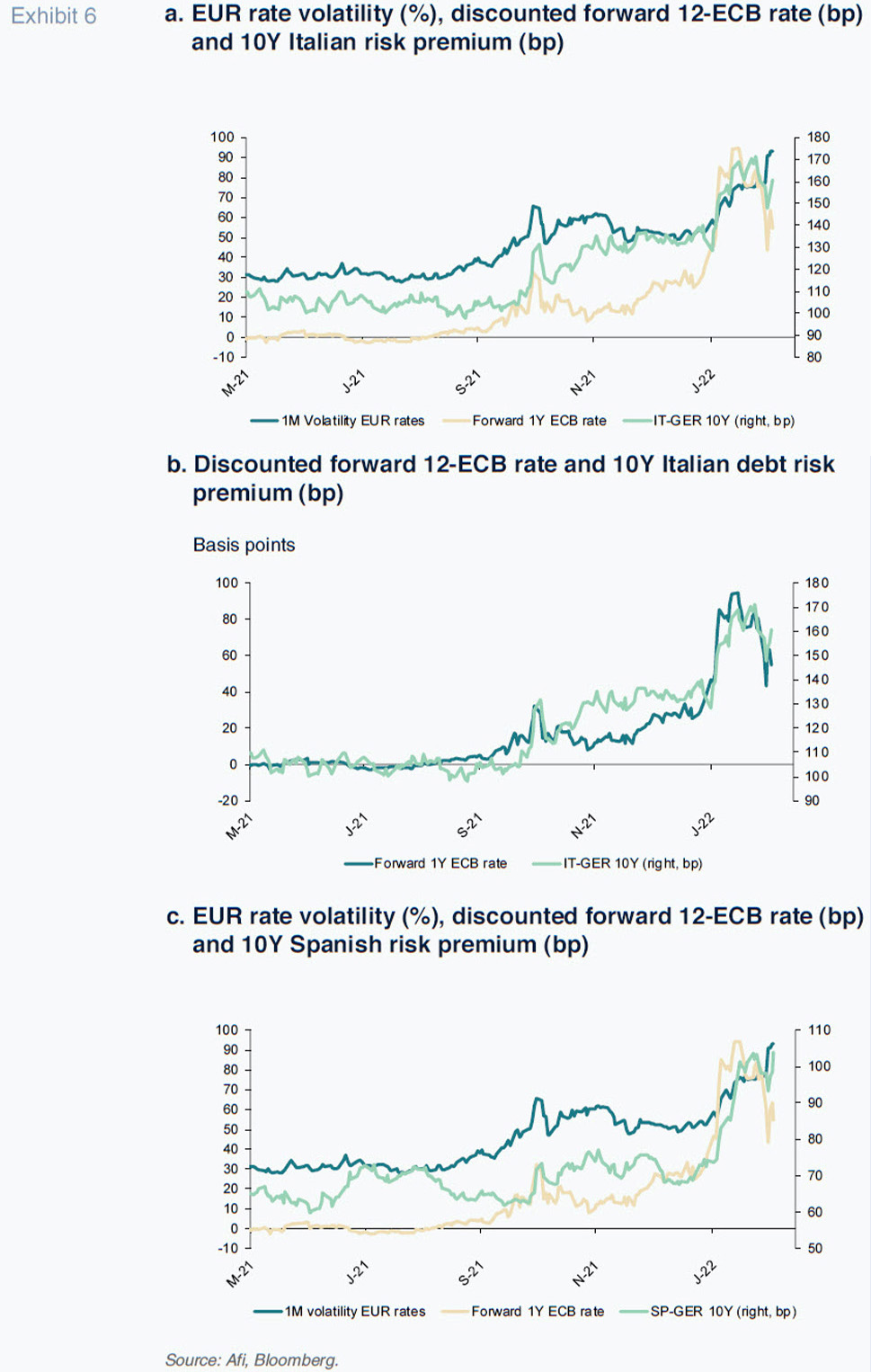

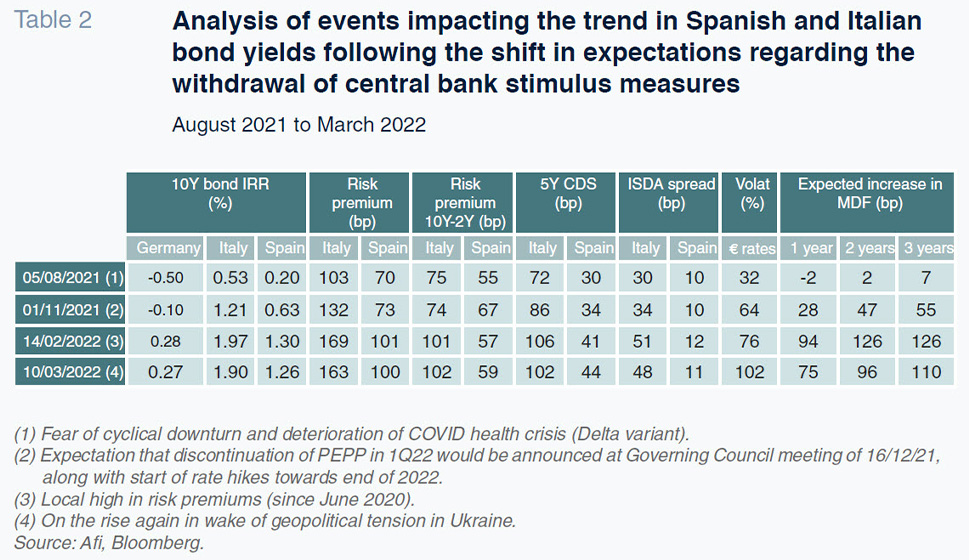

During this second period, spreads between Spanish and Italian 10-year bonds and their German counterparts began to widen, very gradually, from the summer of 2021. That trend accelerated somewhat towards the end of the year, although still at a moderate pace, taking off more considerably in February 2022. At that juncture, the Spanish and Italian risk premiums rose to 100 and 170 basis points, respectively. In parallel to spread widening in the bond markets, CDS spreads began to widen, but by considerably less, reaching just over 50 basis points in Spain and 100 basis points in Italy. In that same vein, signalling very moderate growth in idiosyncratic risk, the slope depicted by the spread between 2-year and 10-year risk premiums not only has not flattened, but has steepened, while the ISDA spread has increased slightly in the case of Italy, while holding stable for Spanish debt. That combination of movements suggests that an increase in idiosyncratic risk has had little to do with the increase in country risk premiums. The first fortnight of war in Ukraine has not had a significant impact on these levels.

In sum, the levels reached by the variables being analysed in relation to peripheral risk premiums during this second episode are well below those attained during the first episode, suggesting that the market perceives that the increase in the risk associated with Spanish and Italian debt is moderate. We can state that, so far, most of the upward movement in the variables used as proxies for the risk premium during this second episode has more to do with the search for a new equilibrium in the relative price of peripheral debt compared to core eurozone sovereigns ahead of an expected change in monetary policy direction (fewer repurchases and rising rates). The rise in bond market spreads, in tandem with the discounting of a benchmark rate hike by the ECB and an earlier end to net purchases of debt, coupled with the volatility in the cost of options over euro interest rates (reflecting uncertainty regarding their outlook), would appear to indicate that the change of tack in monetary policy is the factor weighing most heavily on the recent upward shift in peripheral risk premiums. Exhibits 5 and 6 illustrate the trend in these variables over the last 12 months, evidencing clear-cut correlation since last summer.

We think it is a good idea at this juncture to look back at the sequence of events punctuating monetary policy messaging by the Federal Reserve and ECB between autumn 2021 and today.

- In the US, Fed signals shifted clearly –towards tightening– at the end of November, a shift later confirmed following the FOMC meeting held in mid-December and that meeting’s minutes, which were published mid-January. Sharp economic growth –with the US economy at close to full employment– and the medium-term inflation risk prompted the Fed to move the end of its US Treasury and MBS [7] repurchasing activity forward and to acknowledge in clear terms that it will be necessary to similarly bring key rate hikes forward and to step up their intensity (FOMC members’ median projection for benchmark rates in 2022 and 2023 has increased considerably). Those expectations gained more traction in early 2022 as inflation readings continued to come in ahead of forecasts. The dramatic increase in global geopolitical tension caused by the war in Ukraine is adding additional inflationary pressures, such that bigger and faster rate increases cannot be ruled out.

- In the case of the ECB, expectations for the withdrawal of monetary stimulus, specifically a reduction in repurchasing activity and increase in benchmark rates, began to be reflected clearly in the short-term euro rate curve in early November, a trend that gained intensity from the end of 2021, with the market pricing in a forward 12-month rate of nearly 100 basis points by the middle of February. That trend in rates is underpinned by messaging by the ECB which has become gradually more contractionary as surprises on the inflationary front (higher than estimated readings) increased the probability of non-compliance with the medium-term inflation target and the risk of second-round effects against the backdrop of continued robust economic recovery.

Market expectations that the ECB would announce the discontinuation of the PEPP at the end of March 2022 gained traction in November and early December and were confirmed by the monetary authority at its last Governing Council meeting of the year, on December 16th. Net purchases under the PEPP would indeed be discontinued from March 31st of this year and the ECB would increase the pace of its monthly debt purchases under its legacy programme, the APP, from 20 billion euros at present to 40 billion euros during the second quarter, after which they will be reduced to 30 billion euros in the third quarter and back down to 20 billion by the fourth quarter. Reinvestment of the sizeable volume of maturing principal payments has been left intact for the APP and extended for the PEPP until at least the end of 2024 (by an additional year).

Considering that the monetary policy sequence established by the ECB dictates that –so far– rates will not be increased for some time after the end of net purchasing activity, the market logically interpreted the steps taken to reduce net purchases as a sign that the decision to start to hike rates will also come sooner than initially estimated.

The additional jump in inflation readings in December and January –with a higher number of basket components sustaining sharp price growth– in tandem with signs of ongoing recovery in the eurozone labour market shifted the consensus existing at the time of Governing Council meeting of December, nudging the message towards a more hawkish stance. That shift in message, which was already evident in the press conference given by the ECB’s President, Christine Lagarde, at the Governing Council meeting of February 3rd, and, above all, the declarations made by relevant members of the monetary authority after that meeting, presaged the possibility that the timing of the end of net debt purchases could be brought forward to the third quarter of 2022, with the first rate increase following at the end of the year. At present, as shown in Table 2, the ECB rate discounted by the market has shot up, with the market pricing in a rate of almost 100 basis points in 12 months’ time and assigning a considerable probability to the possibility of a first rate hike at the end of the summer, which logically implies the end of net ECB purchases as early as the summer.

The outbreak of war in Ukraine, intensification of overall risk aversion and the dislocation of global energy prices constitute a negative shock for growth and spell greater inflationary pressures. The intensity of that impact remains highly uncertain and will be key to shaping the ultimate ECB monetary policy response and EU economic policy actions. At the Governing Council meeting of March 10th, the announcement that net purchases under the APP would be slowed (specifically, reduced in the second quarter and potentially discontinued in the third), albeit depending on the trend in inflation and financing terms prevailing in early summer, has increased the probability that the ECB will start to increase rates as early as autumn 2022.

The current environment is propitious for greater risk premium stability relative to prior episodes

At this point of our analysis, we can conclude that in the current episode of spread widening in the eurozone periphery (which began last summer and has accelerated in early 2022), the role of idiosyncratic risk is proving limited; rather, the key variable driving spreads is the search for a new equilibrium price for this asset in the wake of the shift in the monetary policy status quo, as regards both the direction in which rates are headed and the magnitude of net debt purchases.

Looking to the future, attention should focus on three key factors which, in our opinion, will be fundamental in determining whether we could see a substantial increase in risk at the idiosyncratic level with systemic consequences for the peripheral eurozone’s debt markets. Those three factors are: (i) the structural vulnerabilities or imbalances specific to each country; (ii) the degree of progress (or setbacks) in completing the EU´s and eurozone´s institutional architecture; and, (iii) the forcefulness of the ECB’s commitment to limiting the risk of eurozone fragmentation.

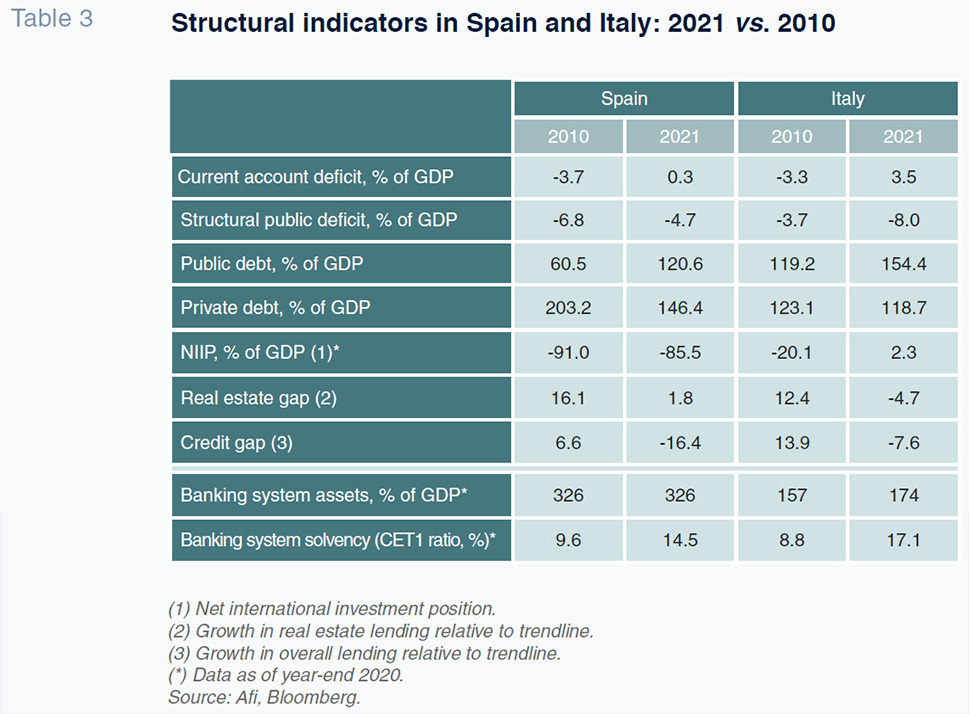

- As regards structural imbalances, we are confident in saying that in both Spain and Italy the degree of vulnerability to the potentially asymmetric impacts of macroeconomic shocks is far lower than before the onset of the sovereign debt crisis at the start of the last decade. Table 3 illustrates that comparison for both economies. Among the various indicators selected to make this point-current account deficit, net international investment position, total borrowings (public and private sector), financial excesses (overall and property sector) and bank capitalisation –the only two not to have improved since 2010 are the ratio of public debt to GDP and the structural public deficit.

- Political instability constitutes additional structural weakness that affects Italy in particular. The government formed by the coalition comprising Salvini’s Lega Nord and the Five Star Movement following the elections of 2018, with their populist measures and markedly anti-European bias, sent investors into a panic: the country risk premium shot above 325 basis points, clearly fuelled by idiosyncratic risk factors. At the time, a significant percentage of the population supported anti-euro and anti-EU positions (around 30%). Today, despite the fact that general elections are still on the horizon, according to the polls, the likelihood of a coalition government formed by Fratelli d’Italia (far right with anti-European leanings) and Salvini’s Lega, with patchy support from the central-right, has fallen, as Italian sentiment towards Europe and the euro has improved (just 17% of those polled for the Eurobarometer of February 2022 expressed opposition to the eurozone), making the possibility of a repeat of the episode of spring 2018 remote. Political risk has been further reduced by the fact that the Five Star Movement has abandoned its anti-European discourse, with Lega similarly toning down its message, together with the long list of structural reforms approved by the current government under Mario Draghi and the sizeable investments in the pipeline thanks to the NGEU funds.

- Even though, as we have analysed in this paper, the incipient change in direction in ECB monetary policy is bound to alter the relative equilibrium price of eurozone peripheral debt, the actions taken by that monetary authority since 2012 constitute, taken as a whole, a key stability factor that limits the probability of a repeat of the episodes of stress in idiosyncratic and systemic risk originating in those countries. From the now famous “Whatever it takes” uttered by Mario Draghi in July 2012, to creation of its tremendously flexible debt repurchase programme, the PEPP (net purchase and reinvestment flexibility), the ECB’s actions have demonstrated the institution’s total commitment to minimising the risk of potential financial fragmentation impeding normal transmission of monetary policy and thereby jeopardising delivery of price stability and eurozone financial stability targets. Turning back to the nearer-term outlook, it is important to note that the end of net asset purchases does not mean the end of debt purchases by the ECB, which will continue to reinvest repayments of the nearly 5 trillion of public and private debt assets on its balance sheet as of February 2022 until at least the end of 2024.

- The last key factor suggesting greater stability in peripheral eurozone risk premiums lies with the progress etched out on the construction of the European project and on completion of the institutional architecture of the EU and eurozone. Although the steps required to reinforce the European project constitute a mammoth task that will surely take time to achieve, a lot of progress has been made during the last decade. That jolted progress has been forced by a succession of crises, as is the way in Europe. The Global Financial Crisis and the eurozone sovereign debt crisis sowed the seeds for the banking union project which, although still incomplete (lack of consensus regarding the implementation of a pan-European deposit insurance scheme), has taken very important steps towards financial stability and crisis management with the creation of the single resolution and supervision mechanisms.

-

The common economic reconstruction effort in the wake of the pandemic, best exemplified by the Next Generation Recovery Fund (NGEU), has been financed from the EU’s common budget, with the EU itself poised to issue more than 600 trillion euros of bonds between 2021 and 2024. Another clear example of the progress made is evident in the so-called European fiscal rules, which, having been suspended following the onset of COVID-19 for a period of three years, will be reintroduced in 2023. They will first be revised, with all signs pointing to rule simplification and governance enhancement so that they fulfil their remit of controlling the member states’ public finances, while eliminating harmful side effects of their implementation as originally formulated.

-

Looking ahead, the new paradigm ushered in by the war between Russia and Ukraine is a wake-up call for the EU in relation to its foreign security and defence, its energy dependence and other considerations of a geopolitical nature hitherto neglected and constitutes an opportunity for taking the EU’s institutional cohesion and stability a step further. The commitment to invest heavily in defence mechanisms at the EU level and resort once again to the issue of common debt to finance that effort is a key vector of that forward thrust. In our opinion, the issue of eurobonds –common debt on global markets– has an impact of similar or even greater proportion than that induced by the ECB’s debt purchase programmes: it sends the market an unequivocal signal that Europe will share costs (of the pandemic, of the war, of whatever comes along) without overburdening individual countries’ debt levels.

Conclusion

The potential withdrawal of monetary stimulus measures marks a very significant milestone for the price of the public debt issued by peripheral eurozone member states. The ECB has been the biggest investor in peripheral sovereign bonds in recent years, acting as a price-taker with the unwavering objective of preventing episodes of financial fragmentation that hinder the correct transmission of monetary policy and increase the risk of financial instability.

The main consequence of the looming change in the direction of ECB monetary policy –probable but subject to significant uncertainty on account of the economic fallout from the heightened geopolitical tension caused by the war between Russia and Ukraine– is that the market needs to define a new equilibrium point for the price of Spanish and Italian debt relative to that of Germany.

Nevertheless, the mitigation of structural imbalances in the peripheral issuer nations, the ECB’s commitment to preventing fresh episodes of financial fragmentation in the eurozone, the progress made in terms of European unity and the gradual fine-tuning of its institutional architecture are all playing a decisive role in reducing the risk of a repeat of episodes of intense idiosyncratic and systemic risk that send the sovereign debt risk premiums of the eurozone’s peripheral issuers soaring.

Notes

We limit our analysis to the trend in Spanish and Italian bond spreads, i.e., excluding Greek and Portuguese debt.

International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

Liquidity is not always observable; it is a concept, not a metric. A good definition of liquidity could be: “In a functional and efficient market, it should be possible to obtain a bid or ask price for a reasonable volume of any instrument at any time.” That price might not be the desired price, but there would be a level at which the bid and ask prices would cross. When markets become ‘illiquid’, that matching does not take place. The liquidity risk of an instrument depends on the ease with which it can be sold at, or very close to, theoretical fair value.

[6]

Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

Mortgage-backed securities.

José Manuel Amor, Salvador Jiménez and Javier Pino. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.