European housing policy insights: Lessons for Spain’s market challenges

Spain’s housing market is under strain due to a persistent supply-demand imbalance, particularly in major urban centers, exacerbating affordability challenges. Lessons from other European countries highlight the need to cut red tape, improve land-use policies, and foster public-private partnerships to boost housing availability and long-term market stability.

Abstract: Spain’s housing market faces mounting pressures, with demand consistently outstripping supply, particularly in major urban areas. In 2022, only one new home was built for every seven new households, exacerbating affordability challenges. While housing policy in the EU varies widely, key initiatives–such as Vienna’s strategic land management, the Netherlands’ social housing financing model, and Ireland’s rental guarantee scheme that integrates private properties into the social housing stock through long-term agreements and tax incentives –offer valuable lessons for Spain. Addressing the country’s housing shortfall requires cutting excessive red tape, improving land-use policies, and fostering public-private partnerships. A coordinated approach across government levels and targeted incentives for affordable housing will be essential to ensuring long-term stability in the Spanish housing market.

Foreword [1]

Housing affordability has become a structural challenge with considerable economic and social implications.

In recent years, the significant growth in housing prices as a result of a growing gap between supply and demand has aggravated the affordability problem. This development, common to many European Union (EU) countries and other regions, is related with global factors such as international financial conditions (IMF, 2024). However, the national markets present unique characteristics that require local analysis.

The Spanish market is notably heterogeneous across segments, social groups and regions. Other factors making it unique include the legacy of the crisis of 2008 and the cultural importance attached to home ownership.

The main goal of this paper is to examine the recent trend in the housing market in Spain and explore relevant economic policies in the EU of relevance for Spain.

Assessment of the housing market in Spain

The early years of the twenty-first century were characterised by a housing market boom. New home-building peaked at around 700,000 a year, fuelled by a credit bubble and massive inflows of foreign capital, channelled primarily into this sector, until the property bubble burst.

The supply of new housing ground to a halt after 2008, just as demand dynamics began to shift. Demand patterns since the financial crisis have been marked in particular by population ageing, changing household structures and migratory flows.

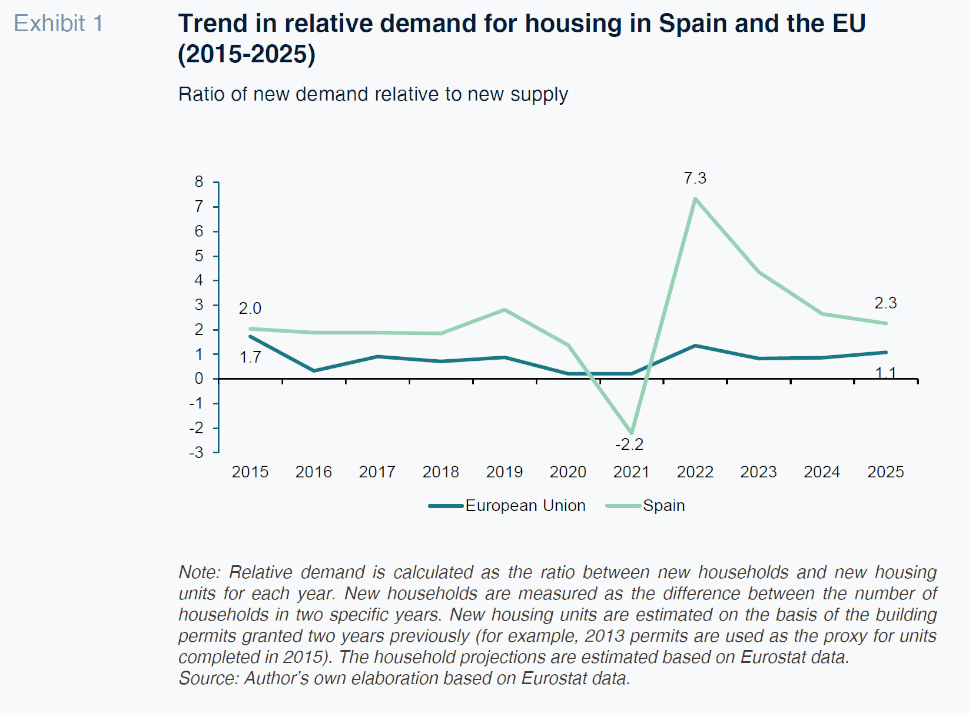

In the last 10 years, the correlation between demand for new housing, measured by new household formation, and the supply of new housing, using building permits as our proxy, has trended in different directions in Spain

versus the EU (Exhibit 1).

In Spain, demand has been consistently outstripping the supply of new housing, translating into a continuous housing shortage. This mismatch peaked in 2022, when only one new house was built for more than seven units demanded. 2021 and 2022 were particularly volatile. In 2021, the ratio turned negative due to the drop in new household creation, whereas in 2022 it shot up, driven by the strong post-COVID recovery and growth in immigration.

Since 2023, the gap has begun to ease as a result of a slight slowdown in growth in demand and some recovery in supply, albeit remaining sizeable. The projections for 2025, based on the Eurostat population figures, suggest that growth in demand for housing in Spain will ease but remain relatively high (at around 300,000 new households), still more than twice the volume of new supply.

In contrast, the EU market has been more stable during the same period. Since 2023, the slowdown in the pace of construction and high growth in household formation is putting more pressure on household demand, unveiling the need for a strong supply response. This trend is expected to continue in 2025, with demand outstripping supply. Note, however, that this ratio is fairly varied across the different member states.

Spain and the EU as a whole have in common the fact that demand is at historically high levels, particularly in Spain. This surplus demand, in a context of a constrained supply response, is driving prices higher and eroding affordability.

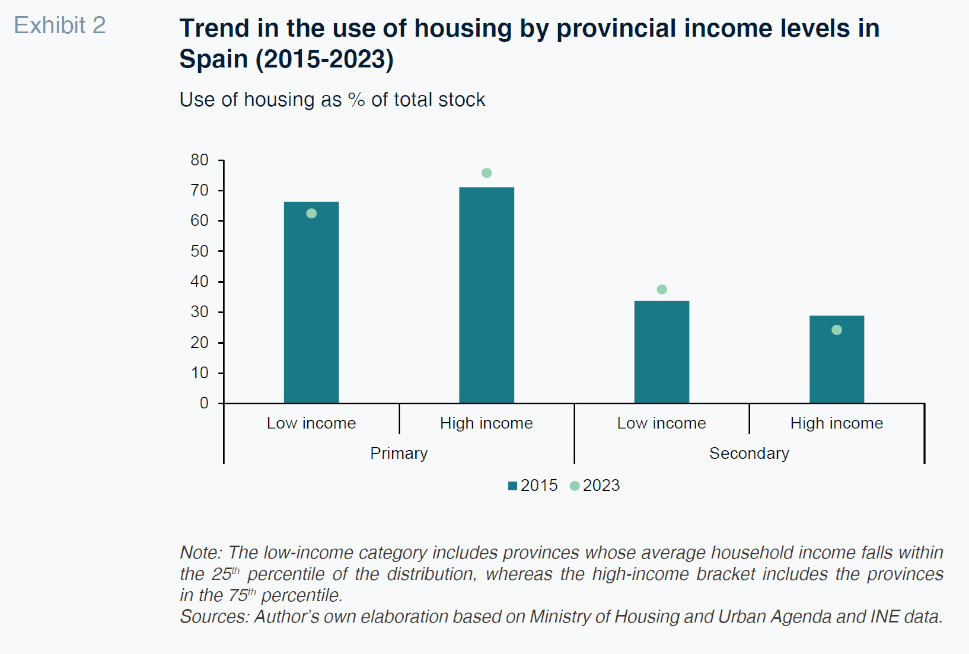

A key aspect of recent dynamics is the fact that in high-income provinces, the supply of primary residences has increased notably (Exhibit 2). This trend may reflect either a more responsive supply structure or stronger market pressure in these areas. In 2015, primary residences accounted for a higher percentage of the total stock in higher-income provinces (71.1%) by comparison with lower-income provinces (66.3%). Over the years, this gap has widened: by 2023, the share of primary residences in high-income provinces had increased by around four points.

In contrast, in low-income provinces, the use of primary residences has decreased while the use of second homes has increased, indicating a potential shift in household preferences, possibly related with limited incentives to move to these markets.

Moreover, these regional differences in the use of housing are coming about in a context of concentration of demand for housing in certain areas. The regions of Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, Alicante and Malaga account for over 50% of the housing shortage in Spain (Bank of Spain, 2024), reinforcing the idea that housing market tensions are significantly concentrated geographically.

There are also considerable differences in the type of housing in demand depending on the region and its level of economic activity. More specifically, rentals are more prevalent in municipalities in which average income per household is higher (20.8%) relative to lower average income municipalities (16.8%). This depicts growth in demand for housing that has not been covered by growth in supply.

Although the stock of social housing has increased in recent years, it continues to represent a very small percentage of the total (around 10%), especially in the rental segment (3.3%). Again, this growth has been uneven by region. Since 2019, the stock of social housing has shrunk by 45% in Castile and Leon, compared to growth of over 400% in La Rioja (refer to Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda, 2025).

Growth in the presence of vacation rentals is another factor restricting the supply of rental housing, particularly affecting areas with greater economic activity. The percentage of rental housing stands at over 50% of the total stock of rental housing in certain specific markets, including Malaga and Alicante (Bank of Spain, 2024).

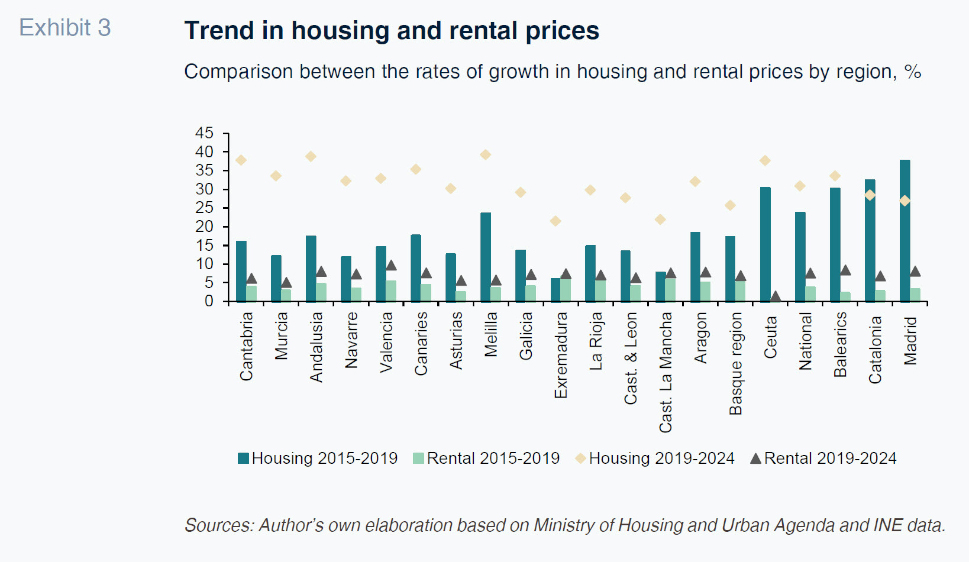

The trend in housing and rental prices in Spain over the past decade reveals patterns that depict the structural imbalances affecting the housing market. The territorial analysis evidences the existence of significant heterogeneity.

Between 2019 and 2024, housing price growth has accelerated in general, at rates significantly above the growth in rents in virtually every region (Exhibit 3). In some markets, such as Madrid, Catalonia and the Balearics, prices have grown by around 30% in the last five years, in contrast with more moderate price growth in the rental segment.

The intensity of the growth in prices indicates that the areas with more dynamic economic activity and higher tourism exposure are experiencing more acute market pressures, confirming the geographic concentration of the housing shortage.

The comparison between 2015-2019 and 2019-2024 reveals that in several regions the rate of growth in housing prices has intensified in recent years. In Cantabria, Murcia, Andalusia and Navarre, price growth has accelerated by more than 20 percentage points in the last four years by comparison with the previous four years. This pattern suggests that the imbalances between supply and demand not only persist but have deepened in certain markets.

Moreover, the growth in sales and prices observed in 2024 is expected to continue in 2025, underpinned by the persistence of the underlying drivers, including growth in disposable income and a relatively comfortable financial situation (Montoriol, 2025).

These dynamics are impeding access to housing, especially for certain groups and in certain markets. This heterogeneity is mainly attributable to the limited supply of rental housing and growing demand from buyers with significant purchasing power (Funcas, 2024).

Lastly, with respect to the possibility of a property bubble, the available evidence suggests that prices are primarily responding to fundamentals factors (refer to the International Housing Observatory reports) rather than widespread imbalances. Nevertheless, it is essential to closely monitor the key indicators to ensure a bubble does not form.

In short, the main challenges facing the housing sector in Spain are: (i) the shortage of supply, particularly in the rental segment; (ii) excessive red tape, especially around the use of land; and (iii) significant heterogeneity by geographic and demographic segments.

Toward improved housing policy in Spain: Lessons from the EU

In the last decade, housing policy has been decentralised in the EU, albeit not uniformly. In Estonia and France, direct administration is shared across the various levels of government, whereas in Germany and Spain it lies primarily with the regional governments.

Housing policies are also remarkably diverse, reflecting different national dynamics and priorities (Caturianas et al., 2020). Only 41% of the member states have a national housing plan, while 52% have implemented rent control measures. In parallel, 41% of the member states have established regulations for guaranteeing minimum housing quality standards. In recent years, measures have also been taken to devise strategies for reducing the number of homeless people. Specifically, 10 member states have included these strategies in their legislation and 16 have homelessness on their strategy agendas for the years to come.

Below is a description of housing policy policies based on four interconnected pillars: (i) land management; (ii) housing supply incentives (both home ownership and rental segments); (iii) expansion of social housing; and (iv) mechanisms for coordinating the housing market participants. The goal is to draw relevant lessons for tackling the challenges facing the housing market in Spain.

Optimisation of land management and availability

Land management has direct consequences for the supply and prices of housing. A sufficient level of available land makes it possible to build at reasonable prices, helping to increase the supply of affordable housing.

Several countries have adopted strategies for refining how they manage their land. The paradigmatic case is Vienna, where housing affordability has not deteriorated the same way as in other EU cities. Since 1994, the city’s housing fund has been championing the construction of quality housing at affordable prices by buying up strategically located sites and organising local tenders among land developers, which are assessed by independent experts. This objectivity is essential to avoiding the auction bias that characterised the Spanish market early this century (Ezquiaga, 2024). The Vienna model has evolved over time, addressing emerging needs such as youth access and including essential services in the developments, while setting aside significant volumes of land for affordable housing.

Its success is based on the fund’s administrative and financial autonomy, the continuity of the related policies and the effective adjudication of the auctions based on objective criteria. In Spain, this continuity could be provided by means of state pacts or the provision of long-term mandates to the competent authorities, whereas auctions would benefit from greater transparency.

One of the main factors limiting supply in Spain is the limited availability of zoned, or ready-to-build, land. A significant percentage of the land available is at earlier stages of the zoning process, implying the need for additional planning and permitting requirements. This lengthens the transformation process and adds uncertainty and costs for developers.

The Netherlands has a specific strategy for simplifying regulations based on the Wabo law, passed in 2010. Under this legislation, all of the physical activities undertaken by a company are covered by a single permit, which is provided by the municipalities. This permit has just three main categories depending on the nature of the activity, significantly reducing the associated administrative burden. Moreover, if an area of land is already covered by an existing town plan, no additional permits are needed. If permits are violated, the authorities are empowered to impose fines proportionate to the breach. This system means that even the most complex developments can be permitted in less than two years, significantly reducing the uncertainty associated with land development.

Spain already has instruments designed specifically to enhance land management, such as the ‘municipal gain’, which represents an ongoing source of financing for the municipal governments. However, the limited availability of ready-to-build land and the uncertainty associated with the acquisition of land considerably constrain the pursuit of residential developments. It is therefore fundamental to provide the local authorities with the regulatory and financial tools needed to speed up land management, take decisions more flexibly and guarantee its effective use.

Incentives to increase the supply of housing for sale and rental

In a context of growing demand pressure, it is essential to ensure that the measures taken do not curb supply dynamics. It is also important to pay attention to the displacement of demand towards the rental market and the intensification of tensions in this segment.

One of the main factors limiting the supply response is the excessive regulatory burden. Reducing this burden could significantly accelerate the start of new developments. In Estonia, the permit processing procedures have been digitalised. In Tallinn, this initiative has helped reduce the average length of time needed to obtain a permit by half in a period of three years, also triggering growth in the number of permits.

The permitting procedure system in Estonia brings all stages of the process into a digital platform based on standardised technical requirements nationwide and proper training of its managers. Adaptation of this system for Spain would require consolidating the governments’ technological infrastructure and harmonising regulatory criteria nationwide.

A focus on certain groups could also ease market tightness in specific segments of the population. Denmark prioritises housing for youths by designing relatively small units accompanied by common-use areas, and through cost-based rents. Simultaneously, the state provides substantial economic aid to full-time Danish students. These policies have helped reduce the age at which Danes leave the parental home to among the lowest in the EU (21.4 years versus 26.3 in the EU in 2023). A similar initiative in Spain could be brought about through agreements between the regional authorities and the universities. It would also be advisable to establish specific quotas for youths in vocational training programmes.

Spain faces substantial challenges regarding housing supply. Initiatives to reduce excessive bureaucracy, such as digitalising and centralising the planning permission process as in Estonia, could foster residential construction. Also, measures targeted at specific groups like young people could help facilitate their access to housing.

Growth and preservation of the available stock of social housing

A small stock of social housing

[2] restricts economic policy’s room for manoeuvre by curtailing its role in correcting market imbalances.

To address these constraints, some countries have developed solid social housing models. The Netherlands, where social housing accounts for 30% of the total stock, compared to 3% in Spain, offers valuable lessons. Since 1995, Dutch social housing developers (woningcorporatie) have been financially independent from the state but benefit from a guarantee fund that channels private capital into affordable housing. However, they benefit from a favourable financing system through the social housing guarantee fund. This mechanism helps channel private capital into this type of housing by providing the developers with guarantees. One of this system’s key strengths is the rigorous nature of the studies carried out prior to awarding the guarantees, which has cemented the fund’s credibility, as borne out by its AAA rating from the main credit agencies. In parallel, an independent national regulator supervises the social housing developments to ensure they comply with the required management and financial standards. Two major advantages of this system are that it does not burden the country’s public finances and the ease with which it could be replicated in other contexts.

The Housing Assistance Payment in Ireland is another good example in this segment. Implemented in 2014, this initiative has gradually incorporated housing into the social stock through the following mechanism: private market properties that meet certain minimum quality and energy efficiency standards can be transferred to the stock of social housing. By means of a contract between the local authority and the owner, the government guarantees the regular payment of a previously agreed and below-market rent and the landlord owner retains ownership of the property while mitigating its risk of non-payment and management costs. The tenants, meanwhile, contribute a share of their income directly to the local authority.

The success of this scheme is underpinned by factors that could be applicable in Spain, including its clear and predictable incentive scheme. Firstly, it offers property owners financial security by guaranteeing full rent collection. Secondly, it significantly simplifies owner management by eliminating the need to look for tenants, which are selected from waiting lists. Thirdly, the scheme features specific tax incentives designed to encourage owner participation.

In Spain a similar system could be implemented while respecting the autonomy of regional governments. They would establish the income requirements and classifications in accordance with their market specifics, whereas the municipal governments could manage the day-to-day operations and tenant selection process. Moreover, in areas where holiday rentals are having a bigger impact, additional tax incentives could be designed for long-term rentals to compensate for the lower return from holiday rentals.

These examples of EU initiatives show that a combination of financial tools, public-private partnership and legal certainty could be vital to widening and preserving the stock of social housing in Spain.

Coordination mechanisms

The housing market involves a significant number of agents, from the public sector to a range of private sector players. One of the biggest housing policy challenges is guaranteeing adequate coordination among the various agents, as the failure to do so can lead to inefficient resource allocation. In addition, it is essential to realise that correcting the existing imbalances cannot be achieved by only one side of the market (public or private); a joint effort by all participants is required.

These coordination mechanisms can be grouped into two categories: mechanisms between different levels of government and between the public and private sectors.

Between levels of government

The fact that housing policy falls to the regional governments poses a risk for residential investment projects as regulatory variation increases uncertainty and potentially fosters a race to the bottom among regions.

Coordination among the different regional authorities can limit this risk. From a theoretical perspective, the different mechanisms can be classified as a function of the intensity of the coordination, which is explained by cognitive, political and institutional factors (Ferry, 2021).

In France, the central government sets national targets for the provision of social housing through its Solidarity and Urban Renewal Act (SRU). This legislation requires the municipalities to maintain a minimum supply of social housing for vulnerable segments of the population. Its legally binding nature and the existence of a penalty regime for local authorities that breach it act as mechanisms for aligning the actions taken at the various levels of government. The law also contemplates distinct targets depending on the urban context, imposing more stringent requirements in tighter markets. Adaptation of this system for the Spanish market could take the form of a framework state law that sets nationwide minimums, while leaving the regional authorities with flexibility around their implementation.

In Finland, the municipal governments have an entity specialised in financing residential projects (MuniFin), which is managed jointly by the local authorities, the central government and the national pension fund. This multi-level governance structure ensures targets are aligned across levels of government. MuniFin issues bonds with high credit ratings secured by a business association (KT). The municipal authorities’ access to this preferential financing (favourable interest rates and extended maturities) is conditional, however, on delivery of specific affordable housing targets. This mechanism motivates the local bodies to actively manage their housing remits and ensures alignment with other levels of government.

Public-private partnership

Mechanisms for collaboration between the public and private sectors are a fundamental part of any strategy for tackling the housing market challenges by leveraging the resources and capabilities of both sectors. The examples already provided reflect, albeit indirectly, forms of collaboration between the authorities and the private sector. The land development tenders in Vienna are a good example of mutually beneficial public-private interaction: the authorities set the quality and affordability criteria, while the private sector brings creative and efficient solutions. In Spain there are also good examples of public-private partnership. García Montalvo et al. (2022) outline a considerable pool of good practices in Catalonia which demonstrate the potential for these alliances in the Spanish residential space.

In a bid to spark interaction between the public and private sectors, several EU member states apply low-cost yet high-impact measures. In the Netherlands, for example, the creation of one-stop-shops has reduced duplicate red tape and construction times. Finland has opted for positive administrative silence, reducing uncertainty for private investors. Initiatives like these could invigorate the Spanish market.

A staggered approach based on pilot projects could also provide an effective way of fostering public-private initiative. Flanders illustrates this possibility. In light of the challenge of bringing about a significant increase in the stock of housing and the scarcity of social housing developers capable of taking on the required volumes, a public-private initiative was put in place. The public sector provided the regulatory framework and some of the financing, while the private companies contributed industrialised construction methods that made it possible to leverage economies of scale. The outcome was significant acceleration of the renewal process, multiplying the housing market’s responsiveness (Housing Europe, 2025).

In Spain, housing competences lie primarily with regional authorities, underscoring the central role of this pillar in the design of these policies. Initiatives such as the harmonisation of taxation across the regions and enhancement of measures such as the transfer of public land could help accelerate permitting processes and curb regional differences. In addition to speeding up administrative processing, these measures would also create a more predictable environment for private investment in affordable housing.

Concluding remarks

The most relevant housing policies share a series of characteristics: public-private partnership, a priority focus on vulnerable groups and tailoring for the specifics of each territory. There is no universal model; rather, interventions need to be adapted for each specific case.

On the basis of the assessment presented and lessons learned from Europe, we can identify three priority lines of action for Spain:

- Bolstering the supply response by simplifying red tape: Excessive bureaucracy is a barrier for the development of new housing in Spain. Implementation of a harmonised digital system like Estonia’s would accelerate construction, particularly in markets presenting more pronounced shortages.

- Developing specific financial incentives for affordable housing: The Finnish model, MuniFin, is an example of how to spur investment in housing without compromising the public accounts.

- Establishing effective mechanisms for multilevel government coordination: The spread of housing powers in Spain underlines the importance of creating effective coordination mechanisms. The creation of one-stop shops like the Dutch example and spaces for efficient collaboration would facilitate regulatory convergence across the regions.

Execution of these priorities should be framed the following key horizontal initiatives: (i) public-private partnership; (ii) specific measures for specific groups; (iii) a balance between the urgency of the problem and the need to think long-term.

Although the EU does not have direct competences in housing, it can also play a key role by monitoring the initiatives taken in each country, promoting new forms of financing and ensuring that the European public funds are used in line with the region’s targets.

In sum, the lessons drawn from European housing experiences provide valuable insight for tackling the challenges facing Spain, tailored logically for the idiosyncrasies of the Spanish housing market.

Notes

The author would like to thank Raymond Torres for his invaluable input. However, the opinions and any possible errors contained in this document are the sole responsibility of the author.

There is no single standard definition of social housing applicable in all countries. For this paper we use the concept in the broad sense. For further details, refer to OECD (2024).

References

ANDRÉS LAJER, A., LÓPEZ RODRÍGUEZ, D., AND SAN JUAN, L. (2024). El mercado de la vivienda residencial en España: Evolución reciente y comparación internacional [The housing market in Spain: Recent trends and international comparison].

Documentos Ocasionales, 2433. Banco de España.

https://www.bde.es/f/webbe/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesSeriadas/

DocumentosOcasionales/24/Fich/do2433.pdf CAIXABANK RESEARCH. Real Estate Sector Report 1H 2025

CATURIANAS, D., LEWANDOWSKI, P., SOKOŁOWSKI, J., KOWALIK, Z., & BARCEVIČIUS, E. (2020).

Policies to Ensure Access to Affordable Housing. Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament.

https://bit.ly/3bAFNMkEZQUIAGA, I. (2024).

El sistema ya no financia burbujas: escasez de vivienda y caída del crédito.

Un análisis del periodo 1998-2023 que cuestiona el modelo residencial español. Estudios de la Fundacion. Serie Economia y Sociedad, no 102. Madrid: Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Estudio_102_Ezquiaga.pdf FERRY, M. (2021). Pulling things together: regional policy coordination approaches and drivers. In

Europe, Policy and Society, 40(1), 37-57,

DOI: 10.1080/14494035.2021.1934985 FUNCAS. (2024).

Mercado inmobiliario y política de la vivienda en España [The property market and housing policy in Spain]. Carbó Valverde, S. (coord.). Estudios de la Fundación. Serie Economía y Sociedad, nº 104. Madrid: Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Estudios104_3.pdf GARCIA MONTALVO, J., RAYA, J. M., SALA, C. (2022). Col-laboració publico-privada en el mercat de l’habitatge a Catalunya (2022). Policy Brief // Cátedra Habitatge i FutuR UPF-APCE

https://habitatgesocial.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/collaboracio-publico-privada-mercat-habitatge-catalunya.pdf INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. (2024). The economics of housing.

Finance and development magazine. KHAMETSHIN, D., LÓPEZ RODRÍGUEZ, D. AND PÉREZ GARCÍA, L. (2024). El mercado del alquiler de vivienda residencial en España: Evolución reciente, determinantes e indicadores de esfuerzo [The rental housing market in Spain: Recent trend, drivers and affordability indicators].

Documentos Ocasionales, 2432.

https://www.bde.es/f/webbe/SES/Secciones/

Publicaciones/PublicacionesSeriadas/DocumentosOcasionales/24/Fich/do2432.pdf MINISTRY OF HOUSING AND URBAN AGENDA. (2025).

Boletín Especial Vivienda Social 2024 [Special Bulletin: Social Housing 2024]. Observatorio de Vivienda y Suelo [Housing and Land Observatory].

Miguel Ángel González Simón. Funcas