Now for the tricky part: Unwinding the European Central Bank’s unconventional monetary policy stance

Outstanding issues surrounding the need for changes to the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy stance are related to timing, not to direction. However, if the European recovery, brought about by these policies, is to be sustained, policy makers must be careful about how and when they withdraw the exceptional measures.

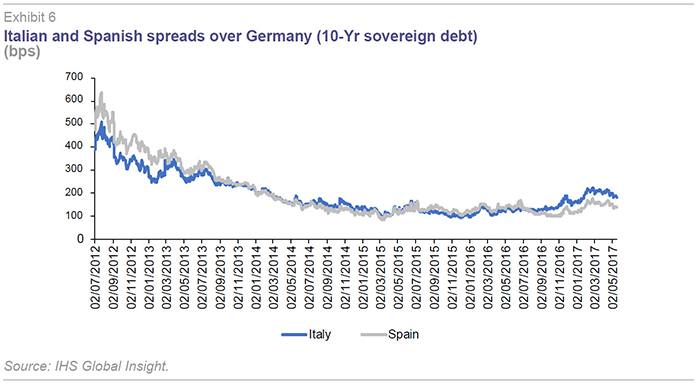

Abstract: The European Central Bank (ECB) should unwind its unconventional monetary policy stance in the near future as inflation expectations across the euro area return to its target for price stability. Doing so, however, will be more complicated than initiating these unconventional monetary policies was in the first place. Part of the challenge is to avoid disturbing sovereign debt markets; shock and awe worked going into the policy, the goal now is to avoid unnecessary volatility. Managing the different impacts of a policy change across euro area countries will be even more important.

Central bankers responded to the onset of the global economic and financial crisis with a burst of innovation, developing an ever-expanding array of new policy instruments to shore up confidence in interbank markets and to underpin faith in bank balance sheets and sovereign finances (Jones, 2010). This innovation culminated in Europe with a series of pronouncements:

- That the European Central Bank (ECB) would do “whatever it takes” to restore the mechanism for transmitting monetary policy decisions across those countries that rely on the euro as a common currency,

- that it would charge negative rates on bank deposits with corresponding central banks that exceed reserve requirements,

- that it would engage in large-scale outright purchases of sovereign debt instruments, asset backed securities, and covered bonds, and;

- that it would reinvest the proceeds of maturing assets on its books in order to maintain the size of its balance sheet.

At each step in this process, the goal of unconventional policy was psychological as well as technical. Borrowing language from the military, central bankers sought to imbue market participants with “shock and awe” to avoid a panic that might lead to disaster

[1].

Now the crisis is passing and the challenge is different. Monetary policymakers need to withdraw their stimulus and unwind unconventional policy positions. Again, the motives are psychological as well as technical. Rather than trying to shock market participants to prevent a panic, however, monetary authorities hope to avoid startling participants in a way that will cause the recovery to stall. This is a delicate operation that relies on transparent signaling and follows a coherent order of operations. The danger is that market participants will rush to judgment in a way that misinterprets policy statements and moves prices in the markets ahead of the policy change.

The ECB cannot afford to fail. Although ECB President Mario Draghi has insisted repeatedly that he has many more instruments available in his policy arsenal, the space for creating additional “shock and awe”

[2] is limited. Unwinding the current posture is necessary if only to expand the ECB’s room for maneuver. Even if that were not the case, the current posture has unintended consequences that accumulate the longer it is maintained. Hence, the ECB must begin this unwinding operation even if the circumstances are not ideal. The next twelve months will be critical to the success of the policy change. Central bankers may learn that it is harder to insulate the recovery than it was to respond to the crisis.

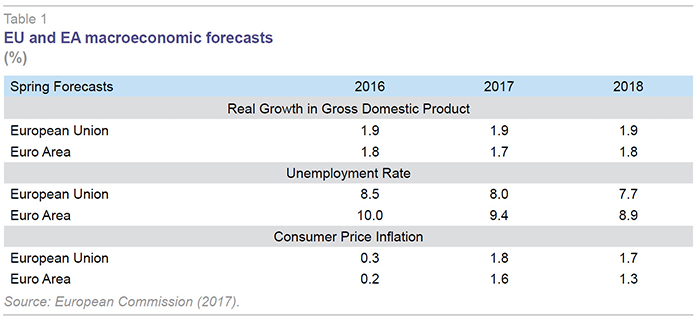

The recovery is taking root

The good news is that the European economy is recovering from the crisis (see European Commission, 2017). The European Commission’s Spring 2017 economic forecasts put aggregate growth for the current year at 1.9 percent across the European Union (EU) and 1.7 percent across the euro area. These numbers are not dramatic but they are consistent. As the forecast document highlights, this is the fifth straight year of improvement. Moreover, the impact is felt across the array of macroeconomic indicators. EU unemployment should fall to 8.0 percent, even as employment growth continues and inflation begins to accelerate. The same pattern emerges from the data for the euro area. Whether this is due to unconventional monetary stimulus or improvement in external conditions is unclear. The ECB has been quick to announce the success of its monetary accommodation; the data for external growth and current account performance suggests that growth elsewhere matters as well. Should that external growth diminish, Europe’s economic performance would suffer. This is one of the “downside risks” that the European Commission’s forecasters highlight. Nevertheless, the consensus view is that conditions are improving, whatever the reason.

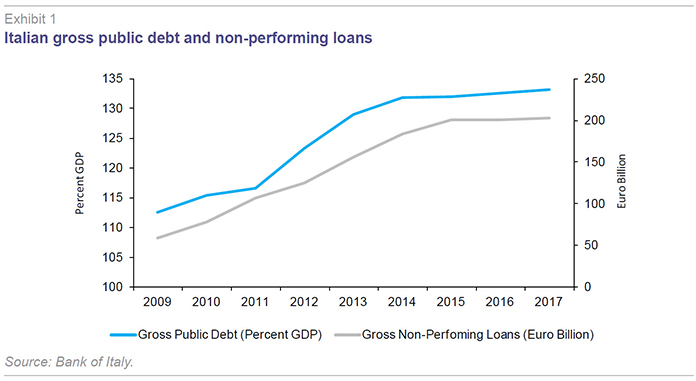

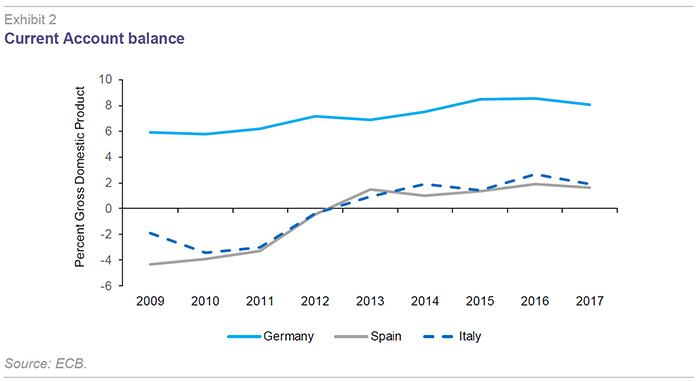

The bad news is that progress is uneven. Some economies, like Spain, are improving rapidly. Growth in Spain is significantly above the European average. Spanish unemployment rates are high, at 19.6 percent in 2016, but they are falling rapidly and should come down by four percentage points in two years. By contrast, Italian growth is much slower than the European or euro area averages. Its unemployment rate is not as high as Spain’s, for example, but employment growth is stagnant and unemployment is persistent. The reason for this discrepancy is hard to pin down. Part may be due to the differences in reform agendas. Spain has undergone more sweeping changes in both product and factor markets than Italy. Part is also due to the legacy of financial weakness. Where the Spanish government grappled with the need to reform domestic financial institutions already in 2012 and 2013, successive Italian governments waited until November 2015. During the intervening period, the volume of non-performing loans in the Italian banking system increased and put downward pressure on the availability of domestic credit and therefore also investment. Now Italy appears trapped in a negative equilibrium where the banks cannot offload their non-performing assets at least in part because of the weakness of economic performance and the economy remains weak because of the fragility of the banks. The relatively high level of public indebtedness in Italy is an exacerbating factor. Despite European efforts to sever the links between sovereign finances and domestic financial institutions, the symbiosis in Italy remains strong and negative.

The contrast between the southern periphery of Europe and the German core is even sharper than the contrast between peripheral countries. The German economy is at or near full employment. German growth is expected to lag somewhat this year and yet it has remained at or above the euro area average for a sustained period. Meanwhile, Germany’s current account is running at just over 8 percent of GDP. The point here is not that Germany is somehow more competitive in Spanish or Italian markets than the peripheral countries are domestically. On the contrary, both Spain and Italy are running current account surpluses as well. There may be competitive differences, but these are no longer the cause of macroeconomic imbalances within Europe. Hence the point is that Germany is enjoying unprecedented global market penetration. The potential for such a large current account imbalance to create problems either in Europe or elsewhere cannot be ignored.

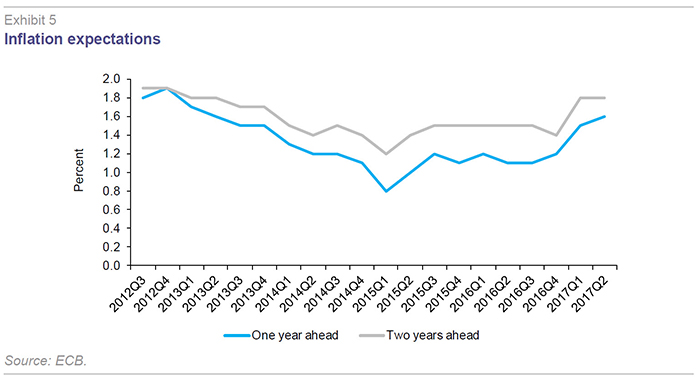

The question is whether a change in monetary policy conditions would offer an appropriate response. This is one of those questions where the asking is more important than the answer. Whatever the merits of criticism levied against Germany’s current account position, it is clear the German government believes (or is willing to argue) that a tighter monetary policy would help. The German government also contends that a tighter monetary policy would be useful to prevent its own economy from overheating and to ease the recovery in countries like Spain (or Ireland) onto a more sustainable trajectory. This line of argument puts the German government in partial opposition to the Italian government and to a substantial share of the ECB’s Governing Council. The claim on the other side of the debate is that the test for the appropriateness of monetary conditions should be framed in terms of the internal balance and not the external balance: Whatever Germany’s current account performance, the important point is the level of growth (Italy) and expectations about inflation in the euro area (ECB). Although inflation has accelerated recently on the back of increases in energy and food prices, core inflation remains subdued and evidence of improvement in medium-term expectations is ambiguous. Therefore, so the ECB maintains, there is still scope for monetary accommodation (Praet, 2017).

The monetary posture needs changing

Any disagreement is more about timing than direction. No-one disputes that the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy stance is unsustainable over the longer term for at least three reasons. One is political, and is that the distributive consequences are both transparent and one-sided – at least superficially. A second is unintended, and is that the policy stance distorts the distribution of liquidity and the availability of high-quality collateral. A third is self-imposed, and is that the different unconventional monetary instruments begin to conflict with one-another over time.

The political argument pits creditors against debtors. Creditors complain that the ultra-low interest rates resulting from charges on excess reserves held by banks and outright purchases of financial instruments by central banks impose a cost on savings while offering a boon to anyone willing to borrow

[3]. Of course, this is an intention of the policy, at least in the short term. When the ECB introduced negative deposit rates for financial institutions, the goal was precisely to create an incentive for those banks to find some other use for their liquidity. Policymakers understood that some liquidity would move abroad and so drive down the euro relative to other major currencies; they also hoped that banks would extend more credit to the non-financial economy. Both influences – the exchange rate channel and the credit channel – would help stimulate economic performance. To the extent that the stimulus would lift economic performance, the benefits should accrue to creditors and borrowers alike.

Over time, however, the distributive implications become more acute. Banks struggle to maintain profitability across a flattened yield curve and they are also reluctant to pass the costs of holding deposits back onto retail clients. More important, longer-term savings vehicles for pensions or life-insurance begin to struggle to match assets and liabilities. They benefit from the short-term capital gains on holdings of sovereign debt instruments or other high-quality marketable paper that gets included in the ECB’s large-scale asset purchasing program, but they lose from the reduction in long-term yields and from regulatory requirements that create incentives to buy assets with a negative yield to maturity. These effects are not immediate and neither are they necessarily mechanical. The longer interest rates remain low on the back of inflated bond prices, however, the easier it is for people to recognize the potential threat to their savings (Jones, 2016).

In the meantime, the presence of the ECB in the market for high-quality tradable assets creates two different kinds of distortions. It pulls those high-quality assets out of the market and so makes collateral increasingly scarce; and it creates an incentive for cross-border investors to liquidate their exposure to high-quality instruments and so repatriate the proceeds back into the domestic market. Policymakers anticipated both consequences although neither was intended. The ECB created a collateral lending facility to attempt to reduce the shortage of high-quality assets. That facility worked less well than anticipated. Although the ECB did manage to lend some of the assets it held outright, the removal of high-quality collateral from private balance sheets gradually created tensions in the interbank market

[4].

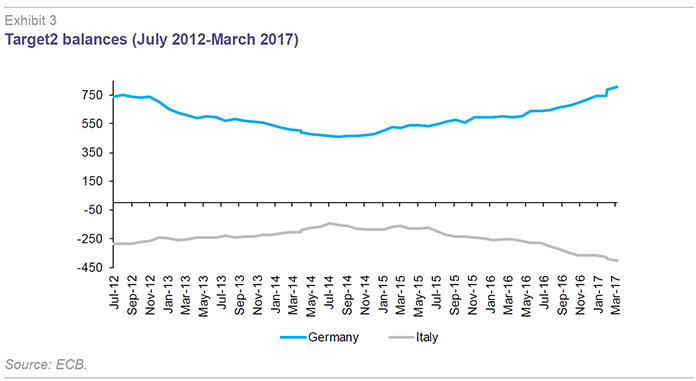

The cross-border transfer of liquidity was more problematic. Foreigners exposed to Italian sovereign debt, for example, had little incentive to seek other, riskier, Italian assets for investment. Hence, once they sold out their exposure to the Bank of Italy as part of the large-scale asset purchasing program, they brought the proceeds back home. This cross-border transfer of private liquidity showed up in the balances of the euro area’s real-time gross payments system (Target2): Italy’s debit position widened as investors pulled their assets out of the country; Germany’s credit position expanded as many of those same assets found their way back home. Here again, there is a problem of public perception: many Germans view the repatriation of liquidity as a net credit to Italy, because of the way Target2 balances are reported, and hence also a potentially risky asset for Germany to hold in the unlikely event that the Italian government should abandon the euro.

The problem of self-imposed constraints emerges from the operational guidelines that the ECB introduced to reassure various stakeholders that it would use its unconventional monetary policy instruments responsibly. The commitment to do “whatever it takes” translates into a pattern of “outright monetary transactions” through which the ECB purchases “unlimited” amounts of a distressed country’s sovereign debt with a residual maturity of three years or less for governments that accept to enter a conditional support program and that request assistance from the ECB. By implication, these “unlimited” purchases are constrained by the volume of short-maturity debt that is available in the market. The more the ECB holds such instruments on its balance sheet, the less it can intervene in the event of duress (and the less incentive a government has to accept conditionality in exchange for ECB assistance).

Self-imposed constraints also emerge from the pattern of ECB asset purchases. The Governing Council has agreed to purchase assets originated in euro-area countries in roughly the same proportions that those countries contribute capital to the ECB – the “capital key”. This means that the large-scale asset purchasing program needs to find approximately 1.46 euros of assets originated in Germany for every 1 euro of assets originated in Italy

[5]. It also needs to find suitable assets to purchase from a long list of much smaller countries, albeit in lesser amounts. This distribution of purchases becomes more difficult to maintain over time given the varying rates of net-issuance across countries and particularly given Germany’s recent success in running fiscal surpluses. The fact that the ECB needs to reinvest the principle of maturing assets on its books in the same proportions that they were acquired makes the situation even more challenging. Eventually, the Governing Council will have to face a choice between maintaining the size of its balance sheet and maintaining the cross-national proportions of its purchases and holdings.

The challenge of unwinding is psychological as well as technical

The ECB’s Governing Council was always aware that it would have to wind up its unconventional monetary positions and so it provided a clear roadmap as to how that will be accomplished, both for individual instruments and for the whole of the policy mix. Some of these guidance notes are more detailed and transparent in terms of content and timing; others are more general and ambiguous. From the outset, for example, the ECB made it clear that the large-scale asset purchasing program would be limited in time and scope. The Governing Council has lengthened the program and expanded its purchases, but it never left any doubt that these actions were temporary as well. So was the decision to reinvest the principal of maturing assets held on the ECB’s balance sheet. Now it is starting to move in reverse. Between March and April, the ECB stepped down the volume of purchases from 80 billion euros to 60 billion euros per month. These reduced purchases will extend until December if necessary. Beyond that date, the level of purchases is likely to wind down even further as the level of inflation expectations shows signs of returning close to but below 2 percent per annum, which is the Governing Council’s definition of “price stability”

The Governing Council will start to raise the deposit rate only once the pace of purchasing has come down. The reason is to avoid delivering a jolt to asset prices

[6]. This risk of a sudden change in prices comes from another self-imposed constraint on ECB purchases. Under normal circumstances, the ECB should not buy assets with a yield that is lower than the deposit rate. In effect, this puts a ceiling on asset prices the ECB will pay. It can purchase above that ceiling if necessary to meet its other restrictions, but so far it has not had to do so extensively. By raising the deposit rate, however, the Governing Council would effectively drop the ceiling. Market participants would adapt their own pricing strategies accordingly. This could create a discontinuity in the markets which would have a negative impact on any financial institution with large holdings of government securities (and that would have to mark its asset portfolio to market accordingly). As the ECB winds up its large scale asset purchasing program, and so plays a smaller role in the market, however, the risk of a rise in the deposit rate creating an asset price shock diminishes accordingly. That is why when Austrian Central Bank Governor Ewald Nowotny suggested that the ECB might raise the deposit rate before winding up the asset purchasing program, his suggestion found little support within the Governing Council (See Siebenhaar and Hallien, 2017).

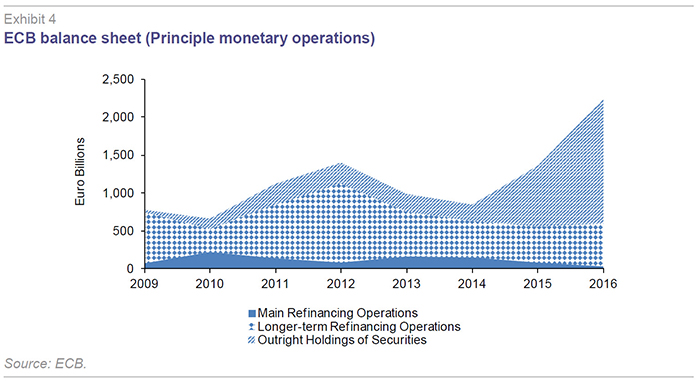

Eventually, the ECB will also need to shrink down its balance sheet. That will only unfold over time and as its existing exposures mature. It is likely also to involve some smoothing through a continued partial reinvestment of maturing assets to account for the lumpy distribution of maturities in the ECB’s current holdings. The ECB has substantial experience with this already. Whereas other major central banks like the United States Federal Reserve or the Bank of England engaged in quantitative easing primarily through outright asset purchases, the ECB relied initially on the accumulation of collateral holdings through its long-term refinancing operations. By implication, the ECB’s balance sheet contracted at the end of the refinancing period when the loans were repaid and the collateral was released.

European market participants are familiar with this pattern and they are aware of the guidance provided by the ECB. Any deviation at this point would create uncertainty for market participants and undermine the credibility of the Governing Council. Depending upon the circumstances, this could result in unnecessary asset market volatility. There may be other, faster ways for the ECB to unwind its unconventional monetary posture, but the benefits of doing so do not outweigh the risks. Instead, most members of the Governing Council seem to agree, it would be easier simply to move through the pre-announced order of operations, using forward guidance to highlight when specific policy changes are likely to take place – slowing down the pace of asset purchases, raising the deposit rate, and then shrinking the exposure on the ECB’s balance sheet.

The next twelve months are critical

Even a systematic approach is not without danger. To explain why, we can look again at the Italian case– although, to be sure, the problem is hardly unique to Italy. The critical data line is the spread between Italian and German long-term sovereign debt instruments. That spread was over 500 basis points when the sovereign debt crisis peaked in the summer of 2012. It fell below 100 basis points around the start of the large-scale asset purchasing program in March 2015. Over the subsequent eighteen months, however, that spread has increased. Now it hovers between 180 and 200. The same is not true for Spain, where the spread is considerably lower.

The reason Italy is under pressure in the bond markets is complicated. The twin challenge of slow growth and non-performing bank assets is obviously important. Another part of the explanation is political and relates to the failure of a constitutional referendum to result in a more decisive government capable of undertaking essential reforms to government finances and market structures. Worse, the failure of the constitutional referendum has left Italy with two different electoral systems for the two separate but equal chambers of the parliament. Hence, there is a risk that new elections to be held when the current parliament ends in 2018 will result in a hung legislature that is incapable of generating a coherent coalition government (Jones, 2017).

The implication is not that Italy will collapse. Rather it is that Italian politicians have a complicated reform agenda to accomplish – completion of financial sector restructuring and clean-up, electoral reform, and fiscal reform to name a few of the top priorities. These things are all possible, but they will take time and effort to accomplish. Having the ECB attempt to unwind its unconventional monetary posture ahead of schedule in this context, would only distract attention from this policy agenda.

What policymakers can learn from this experience

The ECB’s Governing Council engaged in a wide range of experimental policy measures to respond to the global economic and financial crisis. Along the way, the Governing Council also had to shore up the integration of European financial markets. This challenge was not unique to Europe. Other central bankers found themselves in a similar situation and responded in much the same fashion. The pace of change was unprecedented and the policy settings were unfamiliar. Nevertheless, they succeeded in stabilizing economic and financial conditions, which in turn created the conditions for recovery.

Now the challenge central bankers face is very different. In technical terms, they must consider how any efforts to return their instruments to more normal settings will have an impact on asset market performance. This is only to be expected. Any reduction in the large presence that central banks have accumulated in markets for high-quality tradable securities will require substantial adjustment both in terms of the attitudes of market participants and in terms of the composition of asset portfolios in the private sector.

Such adjustment is both necessary and inevitable. Unconventional monetary policies cannot be continued forever. Nevertheless, the implications are not the same for all actors or countries. Central bankers must be sensitive to the different challenges to be faced, nowhere more so than in Europe. If they hope to sustain the recovery they made possible with their policy experimentation, they will have to be very careful about how and when they withdraw unconventional monetary support. Building up large balance sheets starts to look straightforward in retrospect. Bringing them back down again is the tricky part.

Notes

The reference to “shock and awe” is borrowed from the American context. See, Geithner (2015).

These references to Draghi come from his monthly press conferences. These can be accessed online at: http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2017/html/index.en.html.We are not saying that Draghi would agree that the space for additional shock and awe is limited. What he would argue is that monetary authorities cannot do everything on their own.

This point is readily acknowledged by the ECB. See, for example, Draghi (2017).

The ECB was not the only actor creating money market tensions. See Mersch (2017).

The composition of the capital key can be found here: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/orga/capital/html/index.en.html

This insight comes from a member of the ECB’s monetary policy committee.

Draghi, M. (2017), “Introductory remarks at the House of Representatives of the Netherlands,” The Hague.

European Commission (2017), European Economic Forecast: Spring 2017, European Commission, Brussels: 1.

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/ip053_en_1.pdf Geithner, T. (2015), Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises, Broadway Books, New York.

Jones, E. (2010), “Reconsidering the Role of Ideas in Times of Crisis,” in L. S. Talani (ed.), The Global Crash: Towards a New Global Financial Regime?, Palgrave, London: 52-72.

— (2016), “The Political-Economy of Ultra-Low Interest Rates,” Bancni vestnik, 65:11 (November 2016): 7-11.

— (2017), Europe in the Age of Popular Nationalisms,” in Goldstein, A. E., and J. K. Culver (eds), Nomos & Khaos: 2017 Nomisma Economic and Strategic Outlook, A.G.R.A., Rome: 41-52.

Mersch, Y. (2017), “Ructions in the repo market – monetary easing or regulatory squeezing?,” Speech at the GFF summit, Luxembourg, 26 January 2017.

Praet, P. (2017), “Ensuring price stability,” Remarks at the Belgian Financial Forum colloquium on “The low interest rate environment, Brussels, 4 May 2017.

Siebenhaar, H-P., and J. Mallien (2017), “ECB Could Tighten Differently: Austrian Council Member,” Handelsblatt (16 March 2017).

Erik Jones. Professor of European Studies and International Political Economy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and senior research fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford