Weakness in overall construction sector profitability: Low productivity exacerbated by labour shortages

The construction sector in Spain has shown resilience but continues to grapple with low productivity and labour shortages. Addressing these challenges is critical for maintaining profitability and meeting housing demand.

Abstract [1]: The construction sector survived the rout ushered in by the Great Recession, recording steady growth up until the pandemic. As of 2023, its contribution to GDP was around 5.0%, close to the EU-27 average of 5.2%. After the health crisis, the rebound in demand for housing coupled with price growth paved the way for a sharp recovery in sector profitability. However, monetary policy tightening then stalled the trend of expanding margins. The sector has since overcome this difficulty, but the shortage of qualified labour is becoming an increasingly pressing issue, undermining aggregate sector productivity particularly for smaller firms, as labour shortages persist despite a structural improvement in employment conditions. Although the Next Generation EU funds are enormously beneficial for the construction sector, it is vital to search for solutions for the shortage of human capital. Failure to do so could seriously jeopardise firms’ profitability and impede (urgently-needed) growth in the supply of housing.

A decade of resilience and stabilisation

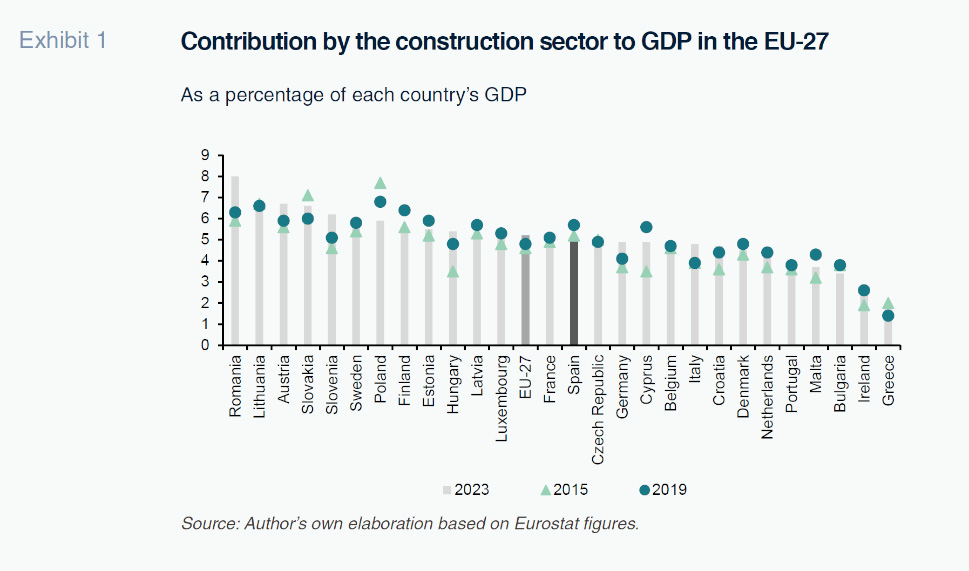

A real estate bubble formed in Spain at the beginning of the twenty-first century, [2] giving the construction sector unusual protagonism, with the sector contributing 10.7% of GDP and 13.4% of employment between 2005 and 2007. [3] However, the Great Recession ushered in major restructuring, and in 2014, the sector generated 5.1% of Spain’s GDP, in line with the European average. Since then, this figure has been very stable, contributing 5.0% of GDP in 2023 (compared to an EU-27 average of 5.2%). Nevertheless, significant structural differences among the European Union Member States remain. As was the case in Spain at the end of the twentieth century, the construction sectors in countries such as Poland a few years back and Romania today generate 8% of their GDP (Exhibit 1).

The excessive size of the construction sector in Spain, and the structural changes induced by the Great Recession, have prompted numerous studies.

[4] This paper seeks to make a dual contribution to that body of work. Firstly, by analysing the sector from a different perspective by using tax records for the construction firms to assess their earnings performance. Secondly, by looking at the last decade, until the third quarter of 2024 (most recent figures available at the time of writing). This period is of particular interest as the fundamental effects of the Great Recession have been assimilated and enough time has elapsed since the pandemic to properly evaluate the sector’s recovery in the wake of that new shock. The database used consists of the aggregate VAT and employee income tax withholding records reported by the sector firms (those incorporated as public limited companies and limited liability companies) to the Spanish tax authority, the AEAT.

[5]

The paper is structured as follows: The following section examines the trend in the gross value added generated by the construction firms. It then analyses the trend in wage costs, going on to look at the players’ performance and profitability through their margins. The paper closes with a synopsis of the main conclusions.

Gross value added generated by the construction firms

Although the construction firms have posted healthy growth in revenue over the past decade, it has not always been sufficient to guarantee growth in value added due to the impact of the cost of materials.

Until 2019, the construction firms’ GVA was increasing at a constant annual rate of 4.6%, in line with a period of economic expansion. The pandemic truncated that momentum, although the subsequent recovery was so strong that GVA increased at a constant annual rate of 7.2% between 2019 and 2022.

Several conditions paved the way for that extraordinary performance. Firstly, new home prices increased faster than the headline rate of inflation,

[6] while material prices remained very stable.

Secondly, there was a very significant increase in new home sale transactions (in mid-2022, the year-on-year pace of growth was 25% above that recorded in 2019). However, in 2023, conditions deteriorated due to an increase in raw material and energy prices (ANCI, 2014), just as the run-up in interest rates curbed demand for new housing. As a result, in 2024, the real change in GVA stagnated, with the sector even recording a year-on-year contraction in the third quarter.

Aggregate sector earnings have been remarkably weak since mid-2022, particularly considering the fact that the macroeconomic variables with the biggest impact on this sector have been performing well in recent months. In fact, the interest rate on new mortgages peaked in October 2023 and revenue continues to rise as house prices continue to register growth of 10.1%, which is well above the average economic growth. Moreover, since the first quarter of 2024, housing transaction volumes are also increasing year-on-year. The growth in construction material prices has ceased with prices actually correcting by 0.65% in the past year.

Moreover, with respect to sector tailwinds, it is important to recall the positive impact of the Next Generation EU funds, a very significant portion of which are earmarked for the rehabilitation of housing and buildings (many of which are public) and the construction and upgrade of infrastructure. By way of example, of the 1,698 tenders called by the central government that had been executed by 31 March 2024, just 11 projects related with infrastructure and the rehabilitation of public state buildings

[7] accounted for 6.56 billion euros of investment (26.09% of all the tenders executed at the state government level. In the case of tenders for funding via local bodies, the aid for “the rehabilitation of buildings under public ownership” amounted to 593.12 million euros (23% of these tenders).

The lack of momentum in GVA in the construction sector is the result of low average productivity and difficulties in leveraging available technological progress. It is true that there is quite a dual track in the construction sector and this productivity drag does not apply to the large firms that are more geographically diversified, operate mainly in the infrastructure sector and can leverage economies of scale. Nevertheless, on aggregate the results imply considerable room for improvement.

The fact that the construction sector presents low productivity on aggregate is nothing new. One McKinsey study (2017) showed that average productivity in the Spanish construction sector decreased between 1995 and 2015, even though productivity at the large firms increased. Specifically, between 2010 and 2014, the top five Spanish construction firms were 175% more productive than the sector average. This productivity gap is also observable in other countries, albeit less pronounced. In Germany, for example it was 89%, while the gap was lower again in France (77%) and the United Kingdom (56%).

It is still interesting to analyse GVA for the universe of sector players as a whole as this is the sum available to the companies for remunerating the productive factors: labour and capital.

[8] Accordingly, if there is no growth in GVA, remuneration of the factors of production will be compromised.

Rising labour costs

Since the construction sector uses labour very intensively and also faces impediments in increasing productivity, it is important to analyse the trend in labour costs in order to generate a snapshot of the companies’ profitability.

In the past decade, the construction firms have created employment at a sharp rate, with the exception of the three harshest quarters of the pandemic in 2020. In fact, since 2021, the construction firms have been hiring at an average annual pace of 4.4%, compared to an average for the overall Spanish economy of 3.8% (according to the Labour Force Survey).

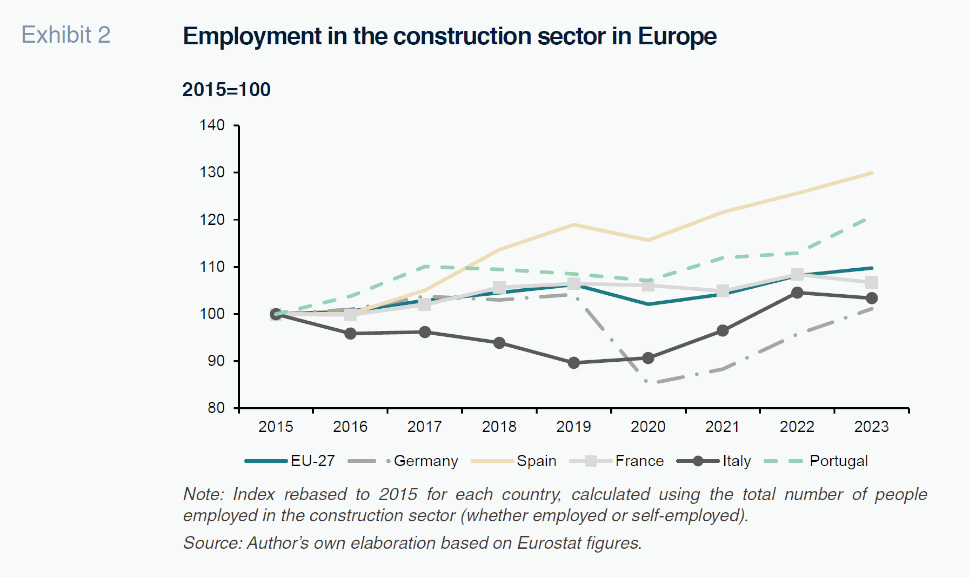

The sharp correction in employment during the Great Recession (when 31% of jobs were destroyed) explains why the construction firms began to hire new workers almost as soon as the economy began to recover. In other European countries, however, fewer jobs were destroyed and the sector did not, therefore, have to hire new workers as soon. This explains why the pattern of job creation has been more intense in Spain during the last decade than the EU-27 average or than that observed in Germany, France, Italy or Portugal (Exhibit 2)- Spain being the only economy to add significant jobs between 2018 and 2019.

Labour costs depend on volume (number of employees) and price (their remuneration). As for average wages, the data reported by the firms indicate that wages did not increase until 2019, but did increase by 3.7% in real terms that year. This trend stagnated during the pandemic and, between 2021 and 2023, construction workers sustained a loss of purchasing power of 3.5% (returning to almost 2015 levels). However, this pattern has since been broken and real wages are now increasing at a similar rate to that observed before the pandemic.

[9] It is important to note that this growth in wages is taking place in parallel with significant growth in employment. In turn, the growth in average remuneration reflects: (i) the hiring of more skilled workers who earn more on average; and (ii) difficulties in finding and retaining less skilled workers without offering higher pay (BBVA Research, 2024).

Another important factor behind the growth in employee remuneration in this sector is the improvement in labour conditions, mainly related with contract types. Firstly, the weight of wage earners or employees has increased gradually, from just 68.2% of all construction sector workers in 2015 to 76.4% by the third quarter of 2024. Secondly, construction is the sector in which the share of employees on indefinite contracts has increased the most: in 2024, 85.3% of employees were on indefinite contracts, compared to 60% in 2019. This is unquestionably a beneficial structural change for sector workers and although it has already translated into higher costs, it should deliver productivity gains in the future.

Weakness in earnings

The other component of GVA relates to capital. The average return on capital at construction firms has tended to be considerably lower than at the rest of the non-financial corporations. In 2015, according to a Bank of Spain report (Bank of Spain, 2023), capital returns in construction accounted for just 27.8% of its GVA, compared to 34.3% for the other non-financial corporations. Although this gap clearly signals low productivity in the construction sector (Observatory of Productivity and Competitiveness in Spain (OPCE), 2024), the bigger concern is that this gap is not closing.

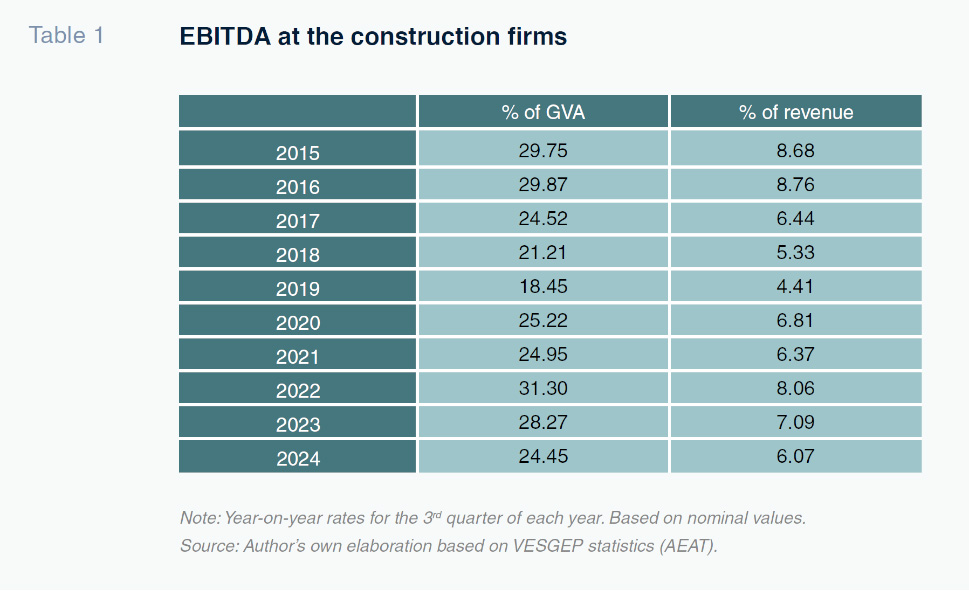

Before the pandemic, the trend in earnings before tax, interest, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) was complicated by the increase in labour costs detailed above, representing just 4.4% of revenue in 2019. The subsequent easing in pressure on labour costs contributed to growth in GVA and, by extension, margin expansion. However, since mid-2022, the increase in material costs, interest rates and wages has eroded the construction firms’ margins, which stood at 6.1% of revenue as of the third quarter of 2024, well below the 8.7% reported in 2015 (Table 1).

By comparison with other economic activities, the weak performance, on average, across the construction firms during the last year is out of sync with the pattern observed across other industrial sectors. That being said, it is true that the construction firms had already revisited – and surpassed – their pre pandemic margins very quickly (in 2022), whereas the industrial companies had not. The main problem currently limiting profitability at the construction firms is the shortage of skilled labour, which is pushing wages higher.

Conclusions

The construction sector survived the rout implied by the Great Recession, eking out steady growth. Moreover, the construction firms reacted very swiftly to the shock induced by the pandemic thanks to sharp growth in new home sales during a period in which house prices also continued to register considerable growth. The advent of obstacles such as higher interest rates or the shortage of skilled labour has put the sector players on alert. In fact, their margins have narrowed over the past year.

The sector outlook remains positive because interest rates are already moving lower, although financing issues and difficulties executing investments could linger. In addition, execution of the Next Generation EU funds should continue to have a positive impact on the sector. The most significant challenge facing the sector is the need to raise its productivity (especially at the smaller firms) in order to tackle a structural change in the labour force that is translating into better labour conditions (permanent contracts and higher pay).

From a broader economic policy perspective, in a context in which demand for housing continues to grow and the housing access problem worsens, it would be advisable for the government to step in and foster worker training at all skill levels. The construction sector needs to remain attractive in order to appeal to skilled workers and boost productivity which has been stagnant for decades despite technological progress and gains at specific companies (mainly large firms).

Notes

The author would like to thank Fernando Arias and Carlos Ocaña for their feedback on an earlier version of this paper. The author alone, however, is responsible for the end product.

At the end of the 20th century, the sector was outsized by comparison with other neighbouring countries (in 1995, is represented 8.6% of GDP). At the time there was a plausible explanation, as a lot of infrastructure (motorways, airports, etc.) was under construction and, although the resident population was not exerting too much pressure on demand for housing, the booming tourism industry was fuelling demand.

To get a better idea of these magnitudes, suffice to note that the industrial sector (manufacturing + energy) accounted for 15.8% of GDP and 15.0% of employment.

Refer, for example, to Albornoz (2010), Cuadrado-Roura (2011), CES (2016), Montalvo (2013 and 2019), Bank of Spain (2023) and Ezquiaga (2024).

Moral (2024) provides a detailed analysis of the database used and of the real estate sector itself.

Between 1Q21 and 1Q24, new house prices increased at an equivalent annual rate of 8.7% whereas the general price index registered growth of 5.4%.

Only including projects that are clearly earmarked for infrastructure and rehabilitation and therefore excluding other projects that may involve several areas, such as infrastructure entailing physical and digital infrastructure or energy infrastructure projects (refer to

https://planderecuperacion.gob.es/).

Gross value added comprises: GVA=CL+GOS. The cost of labour (CL), which includes all wage-related costs, i.e., wages and other costs associated with this input that are paid by the company, including social security payments and termination benefits. The proxy for the remuneration of capital is the companies’ gross operating surplus (GOS), which includes all of the income received by them before the payment of interest and tax and before considering depreciation and amortisation charges.

In the third quarter of 2024, the average real remuneration of employees increased by 3.7% year-on-year.

References

ANCI. (2024). Evolución de los precios de los materiales, la energía y la mano de obra en la construcción [Trend in the prices of materials, energy and labour in construction], Asociación Nacional de Constructores Independientes.

https://ancisa.com/publicaciones/#informesanciBANK OF SPAIN. (2023). Central Balance Sheet Data Office. Annual results of non-financial corporations 2022.

https://www.bde.es/wbe/en/publicaciones/informacion-estadistica/central-balances/BANK OF SPAIN. (2024). Annual report 2023.

https://www.bde.es/f/webbe/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesAnuales

/InformesAnuales/23/Files/InfAnual_2023_En.pdfBBVA RESEARCH. (2024). Spain | The labour market in the construction sector.

https://www.bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/spain-the-labor-market-in-the-construction-sector/CONSEJO ECONÓMICO Y SOCIAL. (2016). El papel del sector de la construcción en el crecimiento económico: competitividad, cohesión y calidad de vida [The role of the construction sector in economic growth: competitiveness, cohesion and standards of living]. Council Documents, 02/2016.

https://www.ces.es/documents/10180/3557409/Inf0216.pdfCUADRADO ROURA, J. R. (2011). El sector construcción en España [The construction sector in Spain]. Colegio Libre Eméritos. ISBN: 2171 - 486X.

https://colegiodeemeritos.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/el_sector_construccion_en_espana_final.pdfEZQUIAGA, I. (2024). El sistema ya no financia burbujas: escasez de vivienda y caída del crédito [The system is no longer financing bubbles: scarcity of housing and contraction in credit]. Estudios de la Fundación. Serie Economía y Sociedad, No. 102. Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/libro/el-sistema-ya-no-financia-burbujas-escasez-de-vivienda-y-caida-del-credito-un-analisis-del-periodo-1998-2023-que-cuestiona-el-modelo-residencial-espanol/GARCÍA MONTALVO, J. (2013). Dimensiones regionales del ajuste inmobiliario en España. [Regional dimensions of the real estate crash in Spain]. Papeles de Economía Española, 138, 62-79.

https://www.funcas.es/articulos/dimensiones-regionales-del-ajuste-inmobiliario-en-espana/GARCÍA MONTALVO, J. (2019). The rental market challenge in Spain. Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 8 No. 2.

https://www.sefofuncas.com/pdf/Montalvo_8.2.pdfGILL DE ALBORNOZ, B., FERNÁNDEZ DE GUEVARA, J., GINER, B., and MARTÍNEZ, L. (2010). Las empresas del sector de la construcción e inmobiliario en España: del boom a la recesión económica [The construction sector and real estate players in Spain: from boom to bust]. Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/libro/las-empresas-del-sector-de-la-construccion-e-inmobiliario-en-espana-del-boom-a-la-recesion-economica-julio-2010/MCKINSEY. (2017). Reinventing construction: A route to higher productivity.

MORAL, M. J. (2024). El sector inmobiliario español: un análisis desde las empresas societarias [Spain’s real estate sector: an analysis through the eyes of its companies]. Funcas.

OBSERVATORY OF PRODUCTIVITY AND COMPETITIVENESS IN SPAIN. (2024). Database.

https://www.fbbva.es/bd/observatorio-productividad-competitividad-espana/

María José Moral. UNED and Funcas