Trump, trade, and investment

The second administration of U.S. President Donald Trump began with a promise to use tariffs and other trade instruments to strengthen America’s economic performance and rebalance its relations with the outside world. The question is whether the European Union can use this challenge to meet its own economic objectives.

Abstract: The second Trump administration moved quickly to use tariffs and other trade policy instruments to push commercial partners of the United States to offer more favourable deals for American firms and to encourage manufacturers to invest in the United States. The European response to this move is to contemplate buying more American liquefied natural gas and military equipment, while threatening a tit-for-tat retaliation with trade instruments. There is still more to do. Europeans could also take the opportunity to negotiate a limited free trade agreement with the United States alongside an agreement for greater mutual recognition of regulatory equivalence. And Europe could strengthen that response over the longer-term by shifting its growth model away from a dependence on exports and greater autonomy in military procurement. Such longer-term responses not only offer the promise of rebalancing economic relations across the Atlantic but also strengthening the transatlantic partnership.

Introduction

The second administration of Donald Trump believes that America’s commercial partners are abusing the rules of the global economy to take away American manufacturing jobs and diminish American prosperity. This belief was already apparent during the first Trump administration, and it is easily found in the pages of Project 2025, which is the policy blueprint created by Trump’s political allies, including many former advisors, during the run up to the 2024 United States (U.S.) Presidential elections (see, e.g., Navarro, 2023; Lassman, 2023). In response, the administration plans to use tariffs and other trade instruments to push China, India, and the European Union into negotiations over trade and industrial policy. The European Union (EU) is aware of this challenge. In anticipation, the EU has developed an anti-coercion instrument to ensure it has adequate countermeasures (Freudlsperger and Meunier, 2024). The European Commission has also floated the prospect of purchasing more U.S. liquefied natural gas and military equipment in any effort to blunt American criticism and so minimize tensions across the Atlantic.

The EU has good reason to push back against the Trump administration’s bargaining tactics. The use of tariffs and other trade instruments to force commercial partners into negotiations undermines the functioning of the rules-based international economic system. Nevertheless, appeals to multilateralism are unlikely to diminish tensions across the Atlantic and a tit-for-tat use of anti-coercive measures will only hurt firms and workers on both sides – as Trump’s own political allies are quick to admit (Lasswell, 2023).

The challenge for European policymakers is to find some way to leverage the Trump administration’s policies to achieve a more balanced and productive relationship with the United States. That challenge is complicated by the rhetoric deployed by the returning president and by the linkage between economics and security within the NATO alliance. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that negotiations with the new Trump administration could fuel a more constructive agenda both across the Atlantic and within the European Union.

Transactional does not mean protectionist

The prospect for constructive bargaining starts from the recognition that the returning U.S. President has few strong ideological commitments, beyond a tendency to engage in transactional bargaining, and his supporters are both varied and divided. This was obvious during his first administration (Barber and Pope, 2019). It remained true during the 2024 Presidential elections. Most voters believe Trump is broadly ‘conservative’, but they disagree on what that means in practice (Pew Research Centre, 2024). Such diversity of views is evident in Project 2025 – which explains why Trump as a candidate could publicly disavow the document even as his allies and advisors could quietly set about planning for its implementation.

That diversity extends to trade policy. Rather than setting out a coherent argument for protectionism, the chapter on trade in Project 2025 is a debate between Peter Navarro, who directed the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy in the first Trump administration and who will come back as Senior Counsellor in the second, and Kent Lassman, who directs the Competitive Enterprise Institute. In the introduction to that section of the report, the editors write that ”Navarro disagrees with Lassman almost across the board” (Dans and Groves, 2023: 658). Navarro (2023) argues for ‘fair trade’ and the aggressive use of trade instruments to push America’s commercial partners into negotiations that could level the competition; Lassman (2023) argues for ‘free trade’ and the elimination of tariffs and non-tariff barriers that disrupt the functioning of global markets.

Navarro’s argument is not necessarily protectionist, at least in the context of the transatlantic relationship. The argument is very different with respect to China, which Navarro regards as a bad faith negotiating partner. Importantly, this negative view of China finds support among Democrats as well as Republicans. This broad suspicion does not prevent U.S. foreign policy elites from imagining a constructive relationship with China, but it does rule out a belief in the virtues and discipline of free markets (Chivvis, 2024). Beyond China, Navarro makes the case for using protectionist instruments to push governments into negotiations. Lassman insists that the use of such instruments inevitably imposes high costs on the United States. That is the main difference between them.

Where Navarro and Lassman agree is on the importance of bargaining to eliminate tariffs or, if that is not possible, to harmonize tariff schedules and so avoid unnecessary distortion of market competition. Navarro (2023: 771) sets out two scenarios, where America’s commercial partners match U.S. tariffs or the United States matches theirs. Lassman (2023: 808, 811) makes the case for negotiating free trade agreements that extend only to tariffs and quotas while at the same time expanding recognition of regulatory equivalence between the United States and its trusted allies, including the European Union.

These openings do not align with the European Commission’s trade preferences. The Commission often negotiates agreements that extend beyond tariffs and quotas to include other forms of regulation for labour, climate action, and consumer protection. These are extensions that both Navarro and Lassman reject. The Commission is also reluctant to recognize regulatory equivalence with foreign jurisdictions, particularly in areas like food safety where fundamental European values come into play. Both the extension of trade agreements ‘beyond the border’ and the reluctance to extend regulatory equivalence reflect the Commission’s reliance on the acquis communautaire (or shared body of EU regulations) to structure the internal market – even at the expense of bilateral or multilateral agreements with other partners (Jones, 2006).

Nevertheless, free trade and recognition of regulatory equivalence do offer pathways to move beyond trying to restore the status quo through the tit-for-tat imposition of new tariffs. The German Christian Democratic Chancellor candidate, Friedrich Merz, acknowledged as much in arguing that the EU should pursue free trade talks with the Trump administration rather than ”a dangerous spiral of tariffs.” [1] Whether or not voters choose to support that option in the upcoming German elections, the opening for such negotiations with the new Trump administration exists.

Trade is not the only imbalance

Trade negotiations can deflect conflict, but they cannot eliminate tensions across the Atlantic. More fundamentally, neither a close alignment on tariff rates nor a broad recognition of regulatory equivalence can change perceptions within the Trump administration that the European Union has some kind of unfair advantage. The measure of inequity, they argue, lies in the bilateral balance on imports and exports – where

the European Union runs a surplus against the United States second only to China (Navarro, 2023: 767). According to data from the International Monetary Fund’s Direction of Trade Statistics, the European Union exported €127 billion in goods to the United States above what it imported in 2016, the year before Trump first took office. That EU surplus increased to €169 billion by 2023, which is roughly 15 percent of the overall deficit in goods trade that the United States has with the rest of the world.

As Navarro acknowledges, tariffs can explain only part of a country’s imbalances. Another part has to do with capital flows, particularly with reference to the current account – which includes the trade in services and investment income in addition to goods like food, raw materials, or manufactured products. From Navarro’s perspective (2023: 793): ”Any deficit in the current account caused by imbalanced trade must be offset by a surplus in the capital account, meaning foreign investment in the [United States].“ The reverse is also true, and any deficit in the capital account must be offset by a surplus in the current account. What this means in practice is that the European Union will continue to run current account surpluses with the rest of the world so long as it continues to send its capital abroad. [2]

Much of that European capital is invested in the United States. In turn, those investments give Americans the purchasing power to acquire more imports from Europe than they can cover with the money they earn from their own exports. And what is true for Europe is also true for China, Japan, and many of the countries of Southeast Asia. The growth models for these countries rely on net exports, which means these countries also tend to accumulate huge volumes of dollar-denominated assets. And the more money they send abroad, the more money Americans can use to pay for additional imports. Indeed, this macroeconomic imbalance – an excessive reliance on net exports for growth – is a large part of the explanation for the risks that accumulated in U.S. asset markets prior to the global economic and financial crisis (Jones, 2009).

Importantly, the European Union did not contribute to macroeconomic imbalances prior to the crisis. Instead, European countries with surplus savings tended to invest in other European countries that offered opportunities for further development. This cross-border investment within Europe is what explains the convergence of nominal bond yields during the late 1990s and early-to-mid 2000s. It also explains the wide divergence in current account balances between the core countries that sent their capital abroad and the countries on the periphery that were the recipients of intra-European investments. The onset of the financial crisis caused those cross-border investments to unwind suddenly, collapsing asset prices on the periphery of the euro area, including in sovereign debt markets. In response, governments in the core countries began to push governments in peripheral countries to adopt export-led growth models while at the same time consolidating their fiscal accounts (Jones, 2015).

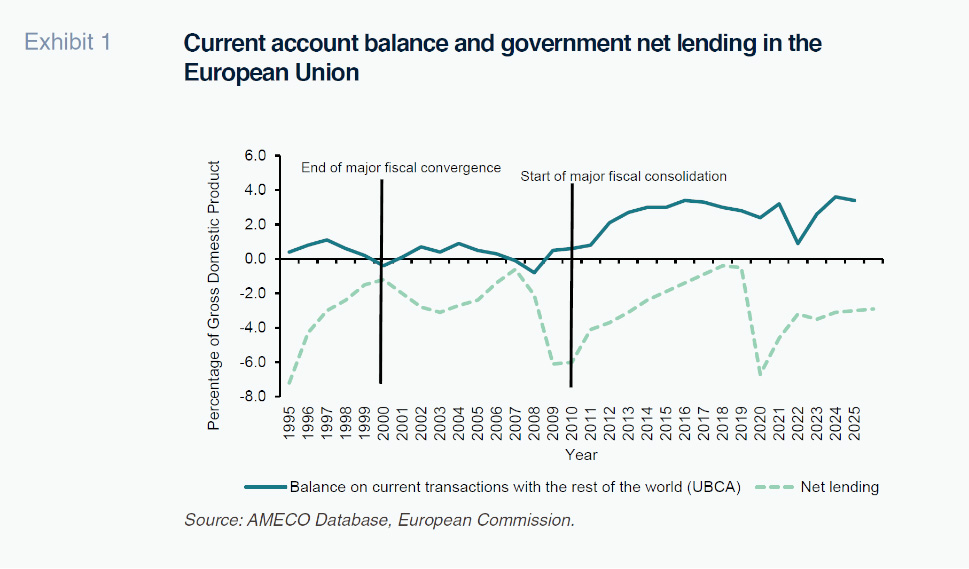

This pattern can be seen in Exhibit 1. On the left-hand side of the figure, EU Member States engaged in fiscal convergence to meet the requirements for entry into the single currency. Once in the euro or likely to join, those countries with opportunities for investment attracted savings from those countries with already advanced industrial economies. After the crisis, however, all European governments embarked on efforts at fiscal consolidation even as banks and other large institutional investors began increasingly to invest European savings abroad.

The European Union now runs consistently large current account surpluses. Moreover, it will continue to do so no matter what tariffs are introduced by the Trump administration. The only way that pattern will change is if European policymakers create the conditions for the private sector to invest across borders within Europe and to accept higher risks on their intra-European investments. Arguably, both a greater appetite for cross-border investment and a higher tolerance for risk would be useful. This is conclusion Enrico Letta (2024) drew in his analysis of Europe’s internal market. And it is a finding that Mario Draghi (2024) underscored in his inquiry into European competitiveness. Both Letta and Draghi insist that European policymakers need to complete their ambition to form a “capital markets union” in order to lower the barriers to cross-border investment. The also argue that governments should loosen restrictions on large institutional investors and create incentives for those firms to take on more risk.

If European policymakers follow Letta and Draghi’s recommendations, they will strengthen the functioning of Europe’s internal market while at the same time laying the foundations for Europe’s future competitiveness. They will also create the conditions for focusing the investment of European savings on Europe. That rebalancing of European savings and investment will reduce the export of European capital and so also the surplus of on Europe’s current account. This will not eliminate the surplus in European trade with the United States, but it will help reduce it. Some European countries will continue to export more to the United States than they import in American products, but for others the situation will be the reverse. Importantly, Trump’s advisors recognize the importance of this macroeconomic rebalancing for Europe’s trade performance. In that sense, European policymakers can sell a credible commitment to the recommendations made by Letta and Draghi as a commitment to reduce Europe’s trade surplus with the United States.

Security is a long-term commitment

Trade is not the only or even the most important source of irritation for the Trump administration or the Republican members of Congress. An even greater friction comes from the link between security and economics. The Trump administration believes that Europeans benefit disproportionately from American spending on military security, and that Europeans use those benefits to undercut American competitiveness. Given the choice between a reduction in Europe’s trade surplus and a sustained increase in European defence spending, many if not most Republicans would put the emphasis on defence – particularly given the threat from Russia and the war in Ukraine (Skinner, 2023: 181-182, 187-188). [3]

The purchase of American weapons for European security is one way to square the circle. Nevertheless, such purchases create divisions among European allies, they reinforce security dependency across the Atlantic, and they draw into question European political commitment to a sustained military buildup. These things tend to weaken and not strengthen the Atlantic alliance. They also tend to reinforce concerns that the European Union is unable to make meaningful security commitments either among its own membership or with neighbouring countries like Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, or in the Western Balkans. Such concerns arise in Project 2025, but they also lie at the centre of the Sauli Niinistö’s (2024: 4-11, 155-163) analysis of the requirements for European security and resilience.

Long-term investment in European defence industries coupled with longer-term contracts for European defence procurement offers another route to security. This strategy does not have to exclude the possibility of procuring American armaments, but it does stress the importance of building up Europe’s own productive facilities, even if that means reimagining the role of state aid in the maintenance of European competitiveness. This is the argument Draghi (2024: Part B, 159-171) makes and Niinistö (2024: 6) reiterates.

What Draghi and Niinistö do not underscore is that investment in defence is another way for Europeans to redeploy their savings within Europe. This is particularly true if European governments borrow funds either for military procurement or to create incentives for more private investment in defence industries. In this sense, greater commitment to military security reinforces efforts at macroeconomic rebalancing even without relying on procurement from the United States. Moreover, Republicans in Congress are likely to accept this line of argument. Since security is their imperative, any improvement in trade relations – however manifest – is just icing on the cake.

Building a constructive agenda would be worth the effort

Embracing this line of argument will be harder to sell within Europe than with the Trump administration. European policymakers will find it hard to embrace a narrow free trade agenda that does not include beyond-the-border considerations. They will also find it hard to accept regulatory equivalence in areas of high political salience, like food safety. Efforts to complete Europe’s capital markets union have been made since the Giovanini report was published in the 1990s but with little real progress. And the scars left by the global economic and financial crisis on relations between core and periphery countries in the European Union are difficult to reverse. It will be even harder to find agreement on making huge investments in European security, particularly if that implies additional public borrowing. The Letta, Draghi, and Niinistö reports attracted attention when they came out, but as yet have generated little momentum for lasting reform. The greatest threat – and likelihood – is that the incoming Trump administration will only distract European attention away from more important policy initiatives that Europeans should be embracing to safeguard the future of Europe.

But there is a chance to use the leverage created by the Trump administration’s use of tariffs and other trade instruments to push in another direction for European policymakers to restart trade negotiations across the Atlantic with a goal to finding areas of possible agreement. They could also use those negotiations as another reason for committing to a reform agenda that Letta, Draghi, and Niinistö argue is essential to secure Europe’s future no matter who is President in the United States. This new agenda will not be easy to accomplish, but European policymakers may have no real alternative. Perhaps the new Trump administration will make it easier for them to focus on what can be gained for Europe.

Notes

A capital outflow is a debit on capital accounts and so has a negative value; a capital inflow is a credit. This explains why Navarro associated a capital account surplus with a current account deficit. When a country imports more than it exports – running a deficit on the current account – then it needs foreign credits to use as payment – a capital inflow, or surplus. The argument here is that a capital outflow provides credits that foreigners can use to purchase more exports from the sending country than it imports.

This insight was reinforced in conversations with Republican Congressional staffers during the transition from the Biden administration to the Trump administration.

References

BARBER, M. and POPE, J. C. (2019). El conservadurismo en la era de Trump. Perspectives on Politics, 17(3), 719-736.

CHIVVUS, CH. (Ed.). (2024). U.S.-China Relations for the 2030s: Toward a Realistic Scenario for Coexistence. Washington, D.C.: The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

DANS, P. and GROVES, S. (Eds.). (2023). Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise. Washington, D. C.: The Heritage Foundation.

DRAGHI, M. (2024). The Future of European Competitiveness, Parts A and B. Brussels: European Commission (September).

FREUDLSPERGER, CH. and MEUNIER, S. (2024). Cuando la política exterior se convierte en política comercial: The Es Anti-Coercion Instrument. Journal of Common Market Studies, 62(4), 1063-1079.

JONES, E. (2006). Europe’s Market Liberalization is a Bad Model for a Global Trade Agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(6), 945-959.

JONES, E. (2009). Shifting the Focus: The New Political Economy of Global Macroeconomic Imbalances. SAIS Review, 29(2), 61-73.

JONES, E. (2015). Unión financiera olvidada: Cómo se puede tener una crisis del euro sin euro. En M. MATTHIAS y M. BLYTH (Eds.), El futuro del euro (44-69). Nueva York: Oxford University Press.

LASSMAN, K. (2023). The Case for Free Trade. En P. DANS and S. GROVES (eds.). (2023). Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise (796-823). Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation.

LETRA, E. (2024). Mucho más que un mercado: Velocidad, seguridad y solidaridad: potenciar el mercado único para ofrecer un futuro sostenible y prosperidad a todos los ciudadanos de la UE. Bruselas: Consejo Europeo.

NAVARRO, P. (2023). The Case for Far Trade. En P. Dans y S. Graves (eds.), Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise (765-795). Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation.

NIINISTÖ, S. (2024). Safer together: Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness. Bruselas: Comisión Europea.

CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN PEW. (2024). El público aprueba por escaso margen los planes de Trump; la mayoría se muestra escéptica de que vaya a unificar el país. Filadelfia: Pew Research Centre.

SKINNER, K. (2023). Departamento de Estado. En P. Dans and S. Groves (Eds.). (2023). Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise (171-197). Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation.

Erik Jones. Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute and Nonresident Scholar at Carnegie Europe