Can the Draghi report save Europe?

The Draghi report provides a transformative blueprint for Europe’s future, emphasizing strategic investments, industrial policy, and governance reforms to boost productivity and competitiveness. However, its ambitious proposals face significant challenges, including political fragmentation, limited fiscal capacity, and resistance to deeper integration, underscoring the need for prioritization of more viable reforms.

Abstract: The Draghi report, published at a pivotal moment for the European Union, identifies structural weaknesses in Europe’s economic model and proposes comprehensive reforms to secure its future. With public and private investment needs estimated at €800 billion annually, the report calls for productivity-boosting measures, enhanced strategic autonomy, and a focus on the green and digital transitions. It highlights the importance of industrial policy, regulatory simplification, and improved governance to foster innovation and competitiveness. However, implementation faces hurdles, including political fragmentation, limited fiscal space, and resistance to deeper integration, underscoring the urgency of prioritizing achievable reforms and embracing a multi-speed Europe.

A turning point for Europe

The Draghi report was published at a key juncture for the European project considering the economic, political and social challenges facing the continent in the coming years: from a loss of competitiveness in a world in the throes of value chain reconfiguration to the financial challenge of having to bolster defence policies in the midst of an energy transition and the recalibration of relations among economies looming with Donald Trump’s return to the Oval Office. Not to mention the challenges associated with future expansion and the need to reinforce the institutional framework. If Europe only advances in times of crisis, as has been the case in the last 15 years with the NGEU funds (health crisis) and Single Supervisory Mechanism (financial crisis), the opportunity for a change of paradigm is currently unbeatable considering the challenging international geopolitical climate. The present Zeintenwende (a historical turning point or change of era) needs to be tackled with ambition to lay the foundations for the European project for the decades to come.

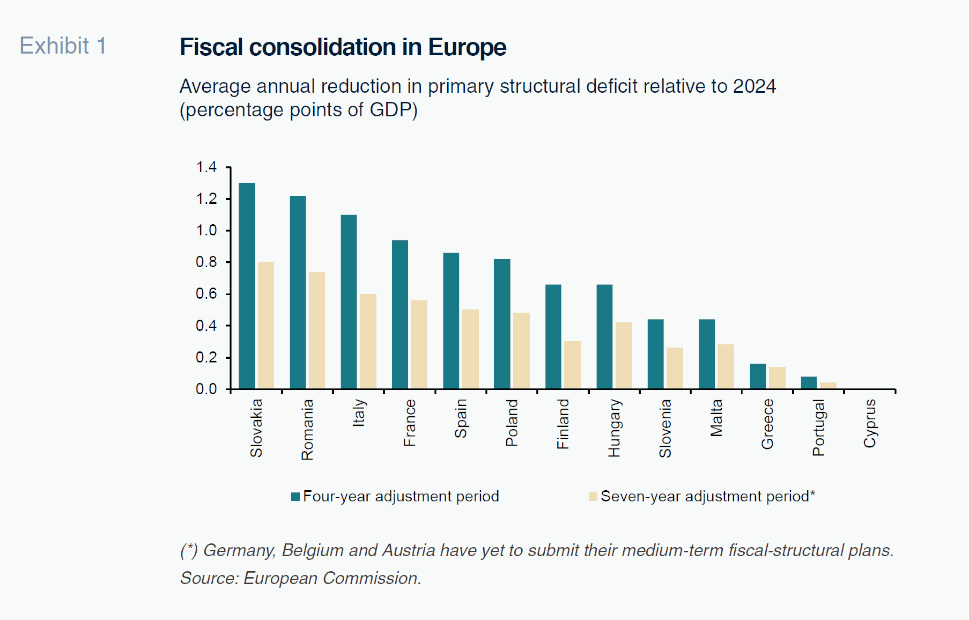

Economic reform priorities remain unchanged from five years ago: completing the Banking Union initiative with a European deposit insurance scheme; making progress on the Capital Markets Union; strengthening the role of the euro as international reserve currency; and creating a European risk-free asset. Now, however, the environment has become a lot more challenging, marked by several open fronts and the need for strategic decisions capable of addressing multiple objectives. The clouds that are gathering on the horizon – new security and defence policy, the need for greater strategic autonomy and the energy transition – will necessarily require a major investment effort. In other words, a huge financial challenge that will require reconfiguring the multi-year financing framework and squeezing it within the boundaries implied by the new Stability Pact (Exhibit 1), as Europe’s buffers have been depleted by a succession of shocks in recent years, as evidenced by the current public debt ratios in both the EU-27 (82.6%) and EMU (89.9%).

Europe, therefore, will have to tackle many challenges with limited room for fiscal manoeuvre. Meanwhile, although the ECB, with its Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), has the ability to mitigate any increase in the risk of fragmentation not justified by economic fundamentals, it also has to continue to taper the size of its public debt portfolio in a very different environment than the one that warranted its intensive use of a non-conventional toolkit.

[1]

All the while, there are additional challenges implied by uncertainty around transatlantic relations (tariffs,

[2] Ukraine, defence policy/NATO) with Trump returning to office, in an environment that looks tricky for the near future in light of the weak growth prospects for 2025 (the consensus forecast is for growth of 1% across the EMU), high dependence on trade for growth, fiscal weakness in France and Italy and the European Commission’s weak starting position (41% of votes went against the new Commission). On top of all of that, we are facing political instability in France and Germany which, in the near-term, will curtail traction in the region’s main engine. So, the outlook for the year ahead is a little bleak. The good news is that the fiscal and political deterioration in a country as important as France (where the risk of “Italianisation” is not insignificant) has only translated into an orderly realignment of risk premiums in the Eurozone, without penalising the peripheral countries. This may reflect the dissuasive power of the web of instruments designed in the past decade to address idiosyncratic crises in the region (ESM, TPI,

etc.). Although we already know from experience that being the target of the financial markets is not the best scenario in times of turmoil, as we are seeing in the case of Britain of late.

Draghi report: A good assessment of how to tackle Europe’s structural challenges

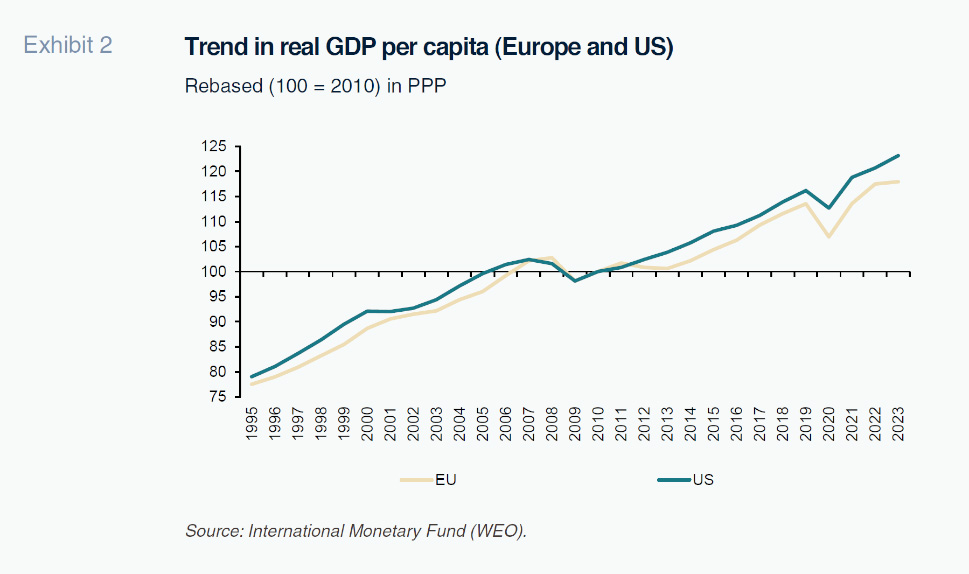

In this challenging context, the Draghi report seeks to reverse the European economy’s structural deterioration, which manifests itself through a weak growth trend, which is evident in the sizeable gap in per-capita GDP by comparison with the U.S.. The GDP gap between the U.S. and EU [3] increased from 15% to 30% between 2002 and 2023, although in terms of GDP per capita (Exhibit 2), the difference has been more stable (34% in 2023 vs. 31% in 2022) due to faster population growth in the U.S. Seventy per cent of the difference in per capita income on either side of the Atlantic is due to differences in productivity, [4] with the remainder attributable to the number of hours worked. If the European economy’s performance of recent decades does not revert, the European social model, which requires strong growth to attend to the needs of an ageing population, especially considering current low birth rates, could be in jeopardy.

However, although the report focuses on how to stimulate innovation and raise productivity, the real culprits of Europe’s stagnation, it also emphasises the change of paradigm in which the global economy is immersed and Europe’s weak position in this new environment. In the current context of deglobalisation and search for strategic autonomy, the European growth model, highly dependent on trade and low-wage-competitiveness,

[5] constitutes a vulnerability, not only because of the issues the Trump administration is expected to prioritise, but also because the surplus of savings relative to investment (3% of GDP on average since 2012) ends up flowing to other areas of the economy in search of higher returns

[6] (as also highlighted in the Letta report

[7]). Against this backdrop, one of the challenges facing Europe is to mobilise the large volumes of savings which households and the rest of the EU’s economic agents have been amassing and channel them into investments in more productive activities in order to escape the “middle technology trap” (low innovation, low investment and low productivity growth).

All the more so considering the investment effort that will be required by the twin green and digital transition.

Therefore, beyond detecting the key variables that explain Europe’s mediocre results in recent decades, the document coordinated by Mario Draghi calls for a full overhaul of the European growth model, particularly in light of the unfolding and looming structural changes in the international order.

One vector and three major challenges

In this context, Europe’s transformation strategy should be articulated around three major challenges: i) raising productivity [8] by reducing the innovation gap with the U.S. and China; ii) accelerating the decarbonisation process in a manner compatible with increased competitiveness; and iii) deepening the continent’s strategic autonomy by increasing security and reducing dependence on imports. All of this should be accompanied by regulatory simplification [9] (a key vector for injecting momentum into the plan) and significant advances in the Single Market (services, capital markets, energy, digital, etc.).

The idea is to make industrial policy the backbone of the entire strategy, taking prominence (and prevailing over, if necessary) over trade and competition policy. The principles of this “new industrial policy” are: i) a focus on sectors rather than companies; ii) investments that are subject to rigorous monitoring; and iii) a focus on technologies where early entry can generate advantages.

All of which implies a considerable shift from the shape of economic policy in Europe in recent decades when competition policy has been prioritised over the creation of national champions. Therefore, the reports lays the groundwork for the reindustrialisation of Europe, combining horizontal actions with a menu of proposals for 10 strategic sectors.

[10] In addition to nurturing key sectors and projects for an innovative climate in Europe, the policy strives to respond to the strategies being pursued in other countries that have tried to attract investment by European companies in recent years, most notably the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The first major objective seeks to deliver a boost in productivity in Europe. If productivity is the result of the combination of innovation at leading large companies, the ability of mature companies to adopt that innovation speedily and the advent of new players that can challenge the rest, Europe compares poorly with the U.S. and China on all three fronts. For example, the start-ups created from scratch in the U.S. in the last 50 years with a market capitalisation of at least 10 billion dollars today (arrivistes) have a combined current market capitalisation of over 30 trillion dollars, which is nearly 70 times more than the market cap of the equivalent population in Europe. In order to stimulate innovation, the report recommends improving coordination of public investment in R&D across the Member States, adopting a single patent system and improving access to finance for innovative firms, favouring the development of venture capital. And pursuing academic and research excellence in parallel.

As for the second major objective, accelerating decarbonisation, Draghi suggests that the EU reorient its support for the manufacture of clean technologies to focus on those in which it is a leader or for which capacity development is of strategic importance (like batteries). One of the measures flagged in this line of initiative is the need to reduce energy prices for end users, as current high prices are a drag for European industry on a relative basis.

[11] To achieve this, the report proposes a range of options that run the gamut from lower tax to modification of the price-setting mechanism so that the low cost of renewable energy has a positive impact on the whole economy and drives network connectivity. It also emphasises the need to develop a genuine Energy Union to unlock the joint purchase of natural gas or crude oil and the development of common strategies in the event of energy emergencies or crises (such as the sharp run-up in gas prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), preventing uncoordinated national responses that could distort the Single Market.

The last objective and lever for increasing competitiveness is reducing dependence on imports and increasing security in today’s convulsive geopolitical environment. The idea of joint purchases crops up again here, in this case in reference to raw materials critical to the green transition. In parallel, development of a more autonomous defence policy is interrelated with beefing up industrial policy by paving the way for development of pan-European companies and greater standardisation and interoperability of equipment across the Member States. This, framed by the need to increase spending on defence (minimum target of 2% of GDP) and the need to heighten the focus on technological development, underpinned by cooperation, pooling of resources and joint orders.

The importance of the horizontal measures

To tackle these major challenges, it is essential to go further on key aspects of the European project, starting with full implementation of the Single Market, [12] which would also foster growth in the business population, improving the ability of the productive apparatus to absorb financing, reducing the risk of bottlenecks such as those affecting the rollout of the NGEU funds.

To achieve all of this, Europe will need to reinforce its governance, expanding the range of issues the Council can rule on with a qualified majority (instead of unanimously) while its budget needs to be made simpler and more flexible, with fewer items and reconfigured priorities articulated around the new objectives. Other proposals for strengthening governance include simplifying and rationalising Europe’s body of laws and procedures and creating a new “Competitiveness Coordination Framework”. All these changes will be hard to implement as they will mean that Europe may advance at different speeds. They will also involve sacrificing some of the most important programmes currently being financed by the European budget (e.g.), with a sizeable political cost in countries such as France.

The second major horizontal reform or building block is the creation of a propitious climate for financing the overhaul of European economic policy, with measures to bring together savings (public and private) and innovation. European households’ savings rate is much higher than that of their American counterparts; however, this has not given investment in the Eurozone a boost, as a good portion of this savings has been placed outside of EU borders.

Therefore, to facilitate innovation investment and financing it is necessary to stimulate, with tax breaks if necessary, the creation of European pension funds, complete development of the Capital Markets Union (which will make the financial channel a more efficient transmitter of monetary policy), stimulate venture capital and make all of that compatible with making the banks’ balance sheets more flexible by developing the securitisation market, so that the banks can release capital unlock additional lending.

What scale of investments are we talking about? According to the report, the volume of public and private investment needed to unlock a step change in the EU’s potential output is estimated at 800 billion euros per annum (nearly 5% of European GDP), financing the public part via the issuance of eurobonds. Delivering this increase would require the EU’s investment share to jump from around 22% of GDP today to around 27%, which would have a very positive impact on cumulative growth (adding 6pp to GDP in 15 years) by comparison with a no-change scenario.

The question is how all these measures would affect inflation and fiscal sustainability, although the potential adverse effects on certain macroeconomic magnitudes would be partially diluted by productivity gains. All of which should be seen against the backdrop of the NGEU funds whose execution is lagging expectations considerably with just 18 months left on the plan. In other words, the eternal question is does the EU have the capacity to efficiently manage and absorb such an ambitious public and private investment programme.

Conclusions

The Draghi report complements the Letta report and is a good assessment of the structural problems facing Europe. The two reports outline a menu of economic policy responses for tackling the challenges originating from a world in the midst of transformation and changing the inertia of the last two decades, combining horizontal initiatives designed to create a healthy general framework with vertical sector-specific initiatives. The overriding goal is to change an economic model no longer suited to tackling the challenges thrown up by a new international economic order.

The proposals made in the reports are very ambitious, particularly those involving investments (800 billion euros); the idea of issuing a “safe” European asset (eurobonds); strengthened governance through the use of majorities rather than unanimous agreement (which could give way to a multi-speed Europe); and the strategic importance attached to industrial policy, to which trade and competition policy would be subordinate.

The warm reception from the European Commission and the ECB signal the report’s potential importance as a guide for the changes Europe needs to take in the coming years. Its impact could be similar to that of the Delors report of 1989 (Report on Economic and Monetary Union) compared to other failed attempts such as Juncker’s White Book. For the time being, however, the German authorities have already expressed their long-standing misgivings about a European safe asset and there are other potential obstacles, including scant room for fiscal manoeuvre and the need to build broad consensus with the social agents and civil society, to name a few. Moreover, with the new European Commission in a weak starting position, internal political fragmentation in the EU does not bode well for implementation of the report’s big ideas considering the rise of the Eurosceptic vote and the persistence of starkly different visions for the pace and depth of economic and political integration, with the Berlin-Paris axis constrained for the very near -term at least.

The solution for avoiding a fresh bout of procrastination in the short-term is to prioritise and advance on the areas where agreement is more plausible, such as: ways to allocate EU resources more efficiently; progress on infrastructure of common interest; measures for reducing the cost of energy; or simplification of the existing regulatory burden. Medium- and longer-term, however, to advance on the most complicated parts of the agenda, there will have to be support for simple majorities in the European Union and, probably, progress on integration at different speeds, given the misgivings certain jurisdictions have about giving up more sovereignty.

In sum, now that the Letta and Draghi reports have properly assessed the challenges in need of tackling, the time has come for action as the degree of ambition displayed in the next legislature will determine the region’s weight in a world headed irreversibly towards division around blocs, increasing the risk of failing to reduce dependence on external energy or technology (AI, chips, etc.) and seeing growth remain in or around “secular stagnation”. Although it may seem like there are too many issues to deal with, the only thing that cannot happen at this crossroads for Europe is paralysis or complacency.

No plan can save Europe from itself, from its tendency to waver, hesitate, put off decisions, revisit the Hamlet-like avatar that has represented the European Union so many times over the course of its history, as Timothy Garton Ash reminds us in his excellent “Homelands. A personal history of Europe”. These tendencies multiply in times of political disorder in the region, with anti-liberal options making inroads. However, the reality is that the twin green and digital transition constitutes a unique opportunity for interrupting Europe’s gentle decline of recent decades and reducing the productivity and per-capita GDP gaps relative to the U.S. It has been done in the past, like at the end of the Second World War and in 1995, when European labour productivity jumped from 22% of the U.S. equivalent to 95% (Draghi, 2024).

The Draghi report may not be the panacea for Europe, but it is a good starting point, for both reflection and action. It evidences how the model followed in recent decades is no longer fit for a global order set to change very quickly in the coming years. And it proposes avenues for tackling a broad spectrum of outstanding challenges, both classical issues (European deposit scheme, Capital Markets Union and European safe asset) and newer ones (twin transition, strategic autonomy, boosting innovation, etc.).

Notes

Having published a new operational framework in 2024, the ECB will undertake a strategic review in 2025. The last one took place in 2021, in a very different context to today’s, with the risk of deflation very present.

3.4% of the EU’s GVA depends on demand from the U.S., with certain sectors very exposed to a tariff war, including the pharmaceutical (22% of GVA depends on the U.S.), chemicals (10%) and transportation (8%) industries.

Using 2015 market prices.

This difference is largely explained by the respective economies’ sector composition (marginal presence of the most productive ITC sectors in the EU).

According to Draghi, growth in real wages has been four times higher in the EU than in the U.S. since 2008.

European institutional investors have placed more funds in U.S. than European shares.

The Letta report titled “Much More Than a Market,” presents a comprehensive analysis of the European Union’s Single Market and proposes strategic enhancements to address relevant challenges.

Particularly considering that according to the Draghi report, by 2040 Europe’s labour force will decrease by 2 million people per annum.

Improvement of the regulatory framework would be propelled by creating a new EU-wide legal status for innovative start-ups (28th regime).

Energy, critical raw materials, digitalisation and advanced technologies, energy-intensive industries, clean technologies, automotive, defence, space, pharma and transport.

The prices paid by European firms for electricity are twice those paid by their U.S. counterparts.

According to the IMF, internal barriers in the Single Market are equivalent to an ad-valorem tariff of 45% for the industrial sector and of 115% for the services sector. In the U.S., these barriers between states are four times lower. With barriers similar to those of the U.S., productivity in Europe would increase by 7% in seven years.

References

José Ramón Díez Guijarro. CUNEF