Eurozone forecasts 2017-2018: Recovery gains momentum but with worrisome country disparities

The eurozone recovery gains traction. However, cross country divergence is becoming more pronounced, weakening the sustainability of the single currency in the absence of a banking union and the establishment of a European fiscal capacity to respond to shocks.

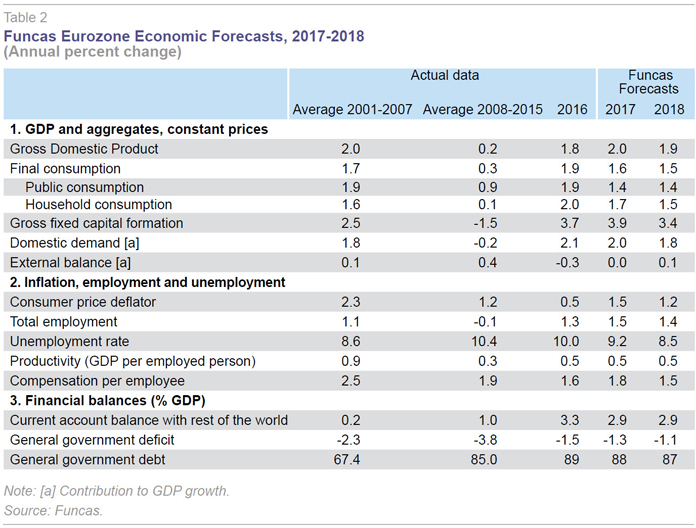

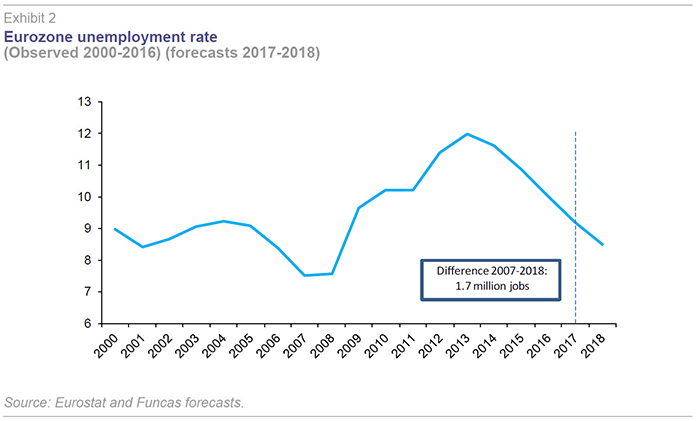

Abstract: The eurozone economy has improved significantly. Recent indicators point to a recovery in both domestic demand and exports. This is due to the continuation of the low interest rate environment, stemming from ultra-expansive ECB policy, the recovery in international markets and increased optimism among consumers and companies. Funcas’ projections are for GDP growth of 2% this year and 1.9% in 2018, making a significant dent in the unemployment rate. Even so, by 2018 the economy is still likely to be 1.7 million jobs short of the pre-crisis employment situation. Furthermore, there continues to be significant divergence across eurozone economies, weakening the sustainability of the single currency.

Recent developments in the eurozone

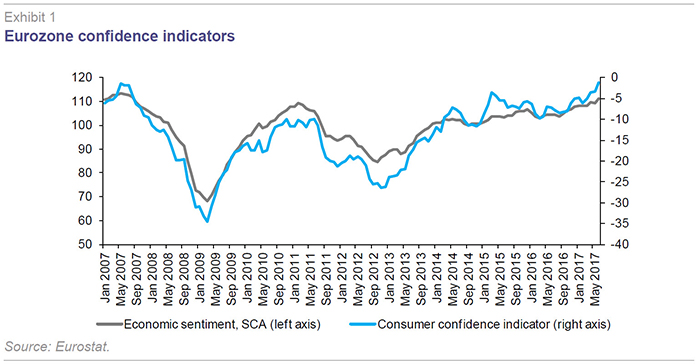

The eurozone economic recovery has accelerated since the start of the year. Activity and consumer confidence indicators have spiked, slightly outperforming pre-crisis levels (Exhibit 1). Meanwhile, international trade flows both within the eurozone and with third countries have increased, in line with the recovery in global markets. GDP grew by 0.6% in the first quarter and 1.9% relative the same quarter of 2016 (Table 1). All countries in the single currency saw a pick-up in growth compared to the last quarter of 2016.

The improvement in the economy is being reflected in the labour market. The unemployment rate has now declined for 38 consecutive months and has fallen decisively over the last year. However, the unemployment rate remains elevated, at 9.3%. Wage income has barely risen in real terms.

This is taking place in the absence of a deterioration in internal or external imbalances. Increasing energy prices have trickled through to headline inflation. However, core inflation (excluding energy and other volatile components) remains around 1%, well below the ECB target. The current account continues to sustain a significant surplus, which amounted to 3.3% of euro area GDP in 2016, the highest since the creation of the Euro.

Finally, the public deficit is on a clear downward trend. In 2016, the aggregate public sector deficit stood at 1.5% of GDP, 0.6 percentage points below the previous year and the second lowest on record (the minimum was in 2007). Public sector deficits fell across all eurozone economies in 2016, except for Austria and Belgium who nonetheless kept their deficits under control. Nine countries posted a surplus (Germany, Estonia, Greece, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands).

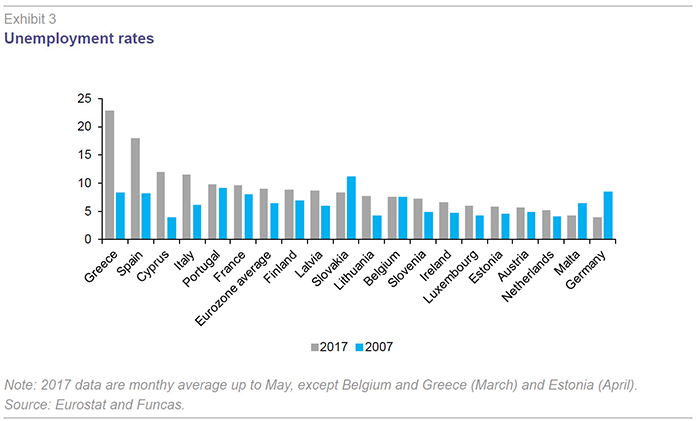

Forecasts for 2017 and 2018

This state of play is set to remain in place for the rest of year, enabling GDP to grow by 2% in 2017, that is 0.2 percentage points more than last year (Table 2). Private consumption will ease slightly due to the impact of the pick up in inflation on household disposable income. Public sector consumption and investment will remain in positive territory, meaning that budgetary constraints have come to an end for most countries.

Investment ‒ both capital goods and residential ‒ will sustain growth rates of around 4%, supported by cheap credit conditions, rising company operating surpluses, deleveraging among non-financial enterprises and the improved overall economic outlook. Altogether, domestic demand will slightly reduce its contribution to GDP growth.

Imports look set to rebound due to euro appreciation and robust domestic demand. However, exports will benefit from the recovery in world trade and the strong position of many European companies in new technologies, facilitating a larger external contribution to growth.

A modest slowdown is expected in 2018 on the back of a likely gradual hike in interest rates and the implications of this for investment ‒ especially residential ‒ and private consumption. The export boom will hold up, thereby making for a positive contribution from the external sector to economic growth.

Employment is set to fall significantly, in line with the acceleration in growth. 4.5 million jobs could be created over 2017-18, with the unemployment rate falling to 8.5%, its lowest since January 2009. However, this will still be some 1.7 million jobs short of pre-crisis employment levels (Exhibit 2).

Energy prices are set to moderate under the assumption of stable oil prices (at around 50 dollars per barrel) and broadly unchanged euro exchange rates (around 1.10 dollars per euro). Headline consumer price inflation will rise to an annual average of 1.5% in 2017 and 1.2% in 2018. Both core inflation and wage costs will remain on a moderate path.

The current account will continue to post a significant surplus, albeit below previous years due to developments in international trade prices (deterioration in the terms of trade). Export prices are likely to grow less quickly than import prices in 2017, due to the increase in oil and other commodity prices. The terms of trade should stabilise in 2018.

Finally, the public deficit is expected to fall, due to the mechanical effect of the recovery on both tax collection and public spending. Excluding these effects, no additional discretionary fiscal measures are envisaged for the eurozone as a whole. Overall, the reduction in the deficit will be insufficient to significantly lighten the public debt burden. This will still stand at around 90% of GDP over the next two years, up 25 percentage points relative to pre-crisis debt-to-GDP ratios. Thus, in the absence of measures to improve budget revenues, the room for fiscal manoeuvre will remain limited.

Disparities remain sizeable across eurozone countries

Geopolitical risks have eased. The European political environment has settled in the aftermath of recent elections in various eurozone countries. However, significant uncertainties remain regarding the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union. Recent elections have only increased uncertainty around the pace of Brexit and its impact on European trade and investment flows.

At the same time, differences across eurozone countries have become more pronounced. Some countries combine high levels of unemployment, low investment, poor competitiveness and significant indebtedness:

- The difference across unemployment rates has increased over the last ten years (Exhibit 3). Some countries with high rates of unemployment have seen a notable improvement as a result of a vigorous recovery, but others have witnessed stagnation.

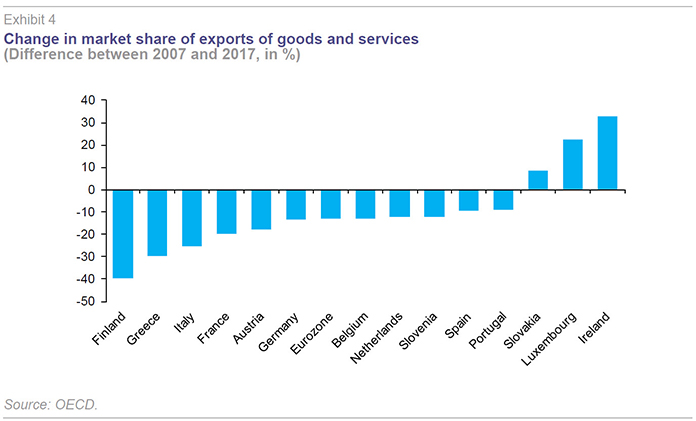

- The latest data point to a significant deterioration in competitiveness in several countries, such as Finland, Greece and Italy (Exhibit 4). The benchmark indicator for this analysis is the volume of goods and services exports as a proportion of the world total.

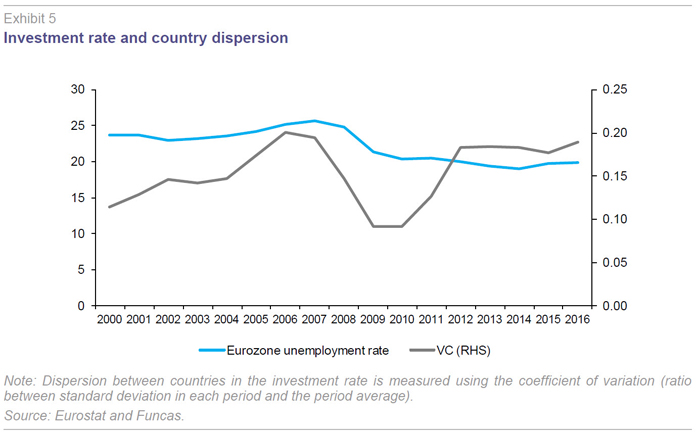

- Investment effort has improved over the course of the recovery, but is still below pre-crisis levels (Exhibit 5). In some countries, the investment rate is barely sufficient to maintain the existing productive capacity.

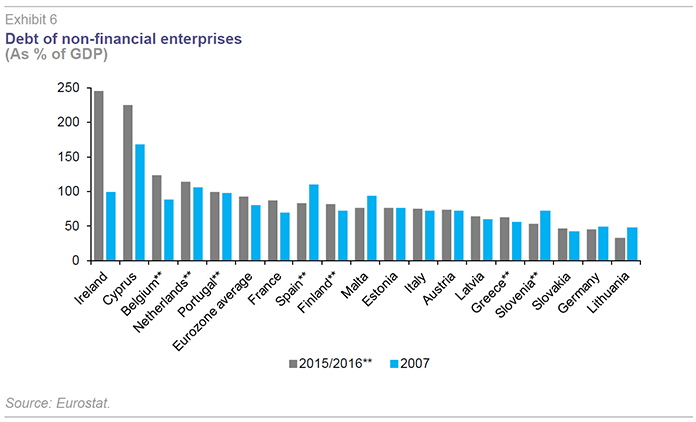

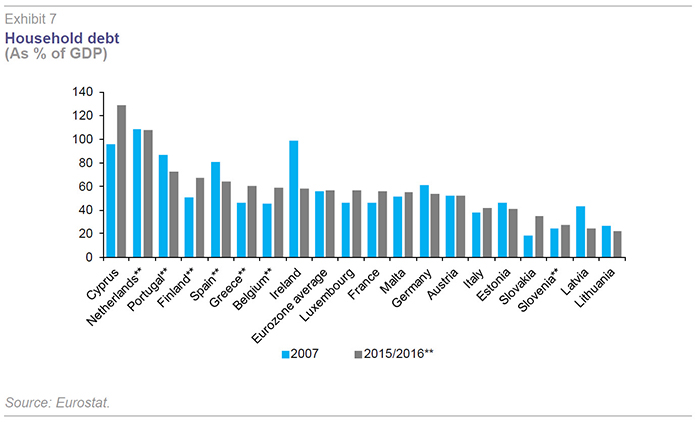

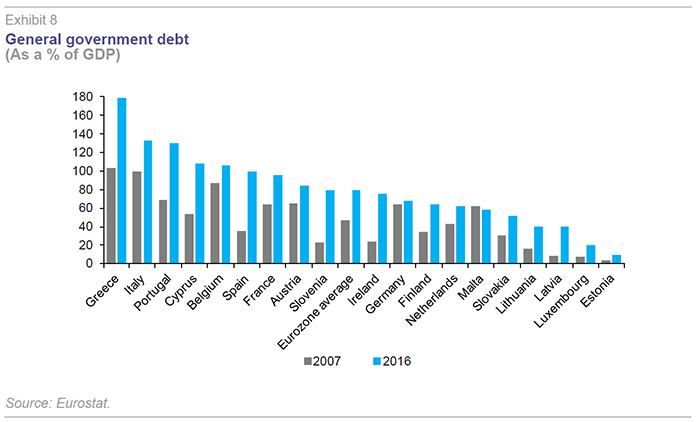

- Empirical evidence and historical experience suggest that deleveraging processes can persist over time, pushing back the recovery. The high levels of debt in some eurozone countries are the result of large deficits recorded at the outbreak of the financial and real estate crises. Corporate indebtedness remains elevated in absolute terms, though as a percentage of GDP it is now at similar or lower levels than before the crisis – except in Cyprus and Ireland (Exhibit 6). The same is true for household debt, albeit with significant differences across countries (Exhibit 7). Household debt to GDP is relatively restrained in most countries, but it is above pre-crisis levels in eleven of the nineteen eurozone countries. (Household debt is particularly high in Cyprus, the Netherlands, Portugal and Finland.) Public debt remains high (Exhibit 8) which poses a major challenge as interest rates begin to rise. The situation makes it crucial for the current pace of economic growth to continue, and for new measures to be introduced with a view to boosting budget revenues and enhancing the quality of public spending.

These disparities weaken the sustainability of the common currency: unemployment is a barometer of a country’s capacity to remain within the eurozone both from an economic and social point of view; countries that face a continuous loss of competitiveness cannot sustain their growth model; investment measures the effort to improve productivity, employment and competitiveness and is essential to solidifying the integration of the single currency; finally, indebtedness is an indicator of financial vulnerability.

Implications for European public policy and for Spain

In the face of persistent divergences, it is essential for at-risk countries to sustain their reform effort. But the functioning of the eurozone itself also needs to be reinforced. Urgent priorities include completing the banking union; ensuring that non-performing bank loans do not derail the recovery; and, strengthening macroeconomic governance in the eurozone.

Some important steps have been made in terms of banking union. The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) are now in operation, albeit with doubts regarding their effectiveness as demonstrated by the recent collapses of various European banks. A fund financed by banks has still to be fully in place, to respond to future bank crises. And the European deposit guarantee fund remains stuck in the pipeline. Moreover, bank portfolios lack sufficient diversification, leading to market fragmentation and hampering the flow of capital and investment.

Non-performing bank loans in various countries remain a source of concern. These portfolios are a reminder of the financial crisis, especially the recession years when bank balance sheets contracted and default rates soared, without being offset by an increase in profitable lending to the private sector. Once again, a sustainable economic recovery accompanied by income growth would help the servicing of outstanding debt and thus improve the quality of certain non-performing loans. Meanwhile, a concerted effort is needed at the European level to tackle the consequences of defaults and avoid contagion effects.

The debate on eurozone macroeconomic governance has intensified. A consensus is beginning to emerge on the limitations of existing instruments. Both the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the “European Semester” are clearly inadequate to handle future recessions. The creation of a European fund ‒ though not necessarily in the form of a new EU budget and treasury, which would raise significant political, institutional and democratic challenges ‒ would be an important step in the right direction. Two possible alternatives are the creation of a pan-European unemployment insurance or a fund for investing in countries in crisis.

It is essential that the different options be assessed and rapid progress made towards reforming the architecture of the euro. The window of opportunity for measured action will shut as soon as monetary policy begins to normalise. ECB action (sovereign and corporate debt purchases and negative policy rates) is masking the eurozone’s unresolved structural weaknesses. But the monetary policy arsenal is set to be progressively reigned in over the next two years.

Finally, within the European context, Spain continues to be an outlier in terms of its strong growth momentum. It is one of the fastest growing economies and is expected to remain so in 2018. Furthermore, convergence indicators are pointing in the right direction. Employment, exports, investment and the deficit are adjusting more significantly than in other countries.

However, the legacy of the crisis continues to weigh down on overall results. Unemployment and public sector debt levels remain the main source of vulnerability and necessitate new reforms to simultaneously lower these imbalances and improve the distribution of the fruits of the recovery.

Undoubtedly, reforms aimed at tackling job precariousness and improving the quality of education would go a long way to consolidating convergence with the eurozone core countries. Meanwhile, further budgetary adjustment is contingent on greater revenue collection efforts.

But domestic reforms are not sufficient ‒ decisive action is also needed at the European level, which would be especially beneficial for Spain. Banks are excessively exposed to national sovereign debt, which in certain circumstances could hamper their ability to finance the economy should the risk premium start to spike. Capital markets union would also facilitate the flow of savings and investment within the eurozone. This would be a welcome development for the Spanish economy, with its abundant supply of labour and relatively high rates of return. Finally, the creation of a European counter-cyclical instrument, such as unemployment insurance or an investment fund, would facilitate a quicker and less socially detrimental response to future recessions.

Raymond Torres and Patricia Stupariu. Funcas