The coming debate about European macroeconomic policy

The debate over the deactivation of the ‘general escape clause’ highlights the tension between the need for active fiscal stimulus and fiscal sustainability. Given the damage wrought by COVID-19 and current debt levels in Southern Europe, the decision ultimately taken by the European Commission will be especially impactful on the region.

Abstract: This spring the European Commission will decide whether to deactivate the ‘general escape clause’ that provided Member States with the fiscal room to combat the economic effects of COVID-19. The main reason for considering a deactivation of the general escape clause is medium-term debt sustainability. At the moment, that does not seem to be a pressing concern. Although debt levels are high as a share of national output, interest rates are at historic lows. The problem comes from the policies which underpin the current low interest rate environment – namely ECB asset purchases. Significantly, the ECB’s pandemic emergency purchases do not have to be proportionate across countries except across the life of the program. As a result, they skew heavily toward sovereign debt issued by governments in Southern Europe. The challenge going forward is to balance the need for active fiscal stimulus in the short-term with the requirements for fiscal sustainability in the medium-term. The tension between these two goals was evidenced over the pandemic-related credit facility within the ESM. For Southern Europe, this pressure is particularly pressing given the difficulty of balancing the need for sustained, productive investment on the one hand, and the necessity of fiscal consolidation on the other.

Introduction

In mid-spring 2021, the European Commission will start a conversation about deactivating the ‘general escape clause’ that is written into the procedures for macroeconomic policy coordination. That conversation should conclude by June. The most likely result will be either a return to the rules that existed before the novel coronavirus pandemic with effect for the 2022 fiscal cycle or an extension of the general escape clause for another year. It is also possible that European policymakers will try to change the rules for fiscal cooperation in light of the ongoing economic crisis. Such reforms are not unprecedented. The downturn that hit Europe’s economy in the early 2000s sparked one set of reforms; the economic and financial crisis a decade later motivated another. The European Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs and the euro, Paolo Gentiloni, recently insisted that a third set of reform should be on the table after this crisis (ANSA, 2020).

Whatever the outcome, the conversation about deactivating the general escape clause will have a major impact on the conduct of European macroeconomic policy both at the national level and, by extension, on the development of the European Union’s recovery and resilience facility (Jones, 2020b). Deactivating the general escape clause without reforming the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination would create a powerful disincentive for Member States to borrow money either from the European Commission or from the European Stability Mechanism, or to replace that borrowing with nationally issued public debt. Extending the general escape clause without reforms would create ambiguous incentives for public borrowing, particularly with respect to longer-term productive investment. Only by reforming the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination will the EU create incentives for Member State governments to use the recovery and resilience facility aggressively. Given the recent changes to the European Stability Mechanism, however, such reforms to the pattern of macroeconomic policy coordination are unlikely.

This argument has four sections. The first introduces the ‘general escape clause’ within the broader framework for European macroeconomic policy coordination. The second explains why there is pressure to deactivate that exception. The third suggests how the introduction to the European Union’s new recovery and resilience facility collides with recent changes made to the treaty for the European Stability Mechanism to complicate the conversation about either relaxing or reforming the pattern of macroeconomic policy coordination. The fourth section concludes with implications for Southern Europe.

The general escape clause

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (the ‘Council’) added the general escape clause to the legislative procedures for enforcing the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) in 2011. This reform was part of a ‘six pack’ of measures designed to strengthen the surveillance of budgetary positions within the Member States by the European Commission after the global economic and financial crisis. The clause does not set aside the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination, but it does give the European Commission enhanced flexibility in interpreting those rules – particularly with respect to excessive debts and deficits. The clause can be triggered by the Council upon a recommendation by the Commission ‘in the case of a severe economic downturn in the euro area or in the Union as a whole’. The only requirement is that any enhanced flexibility in applying the existing rules ‘does not endanger fiscal stability in the medium-term’. This language appears in various forms in both Regulation (EC) No 1466/97 and 1467/97, as amended. The European Commission called for the application of the general escape clause on March 20th, 2020, and the Council accepted that recommendation three days later. This was the first time the clause has been used.

The application of the general escape clause had important consequences for how the Commission treated the fiscal measures implemented by the Member States to blunt the economic impact of COVID-19. The regulations amended in the ‘six pack’ legislation place a strong emphasis on the level of public debt as a ratio of gross domestic product (GDP). Such ratios should not rise above a reference value defined in a protocol to the 1992 Maastricht Treaty as 60 percent. If they do, the Member State in question should make efforts to ensure that any differential decreases ‘at an average rate of one twentieth per year as a benchmark’ until the stock of debt relative to GDP is brought back down to or below the reference value.

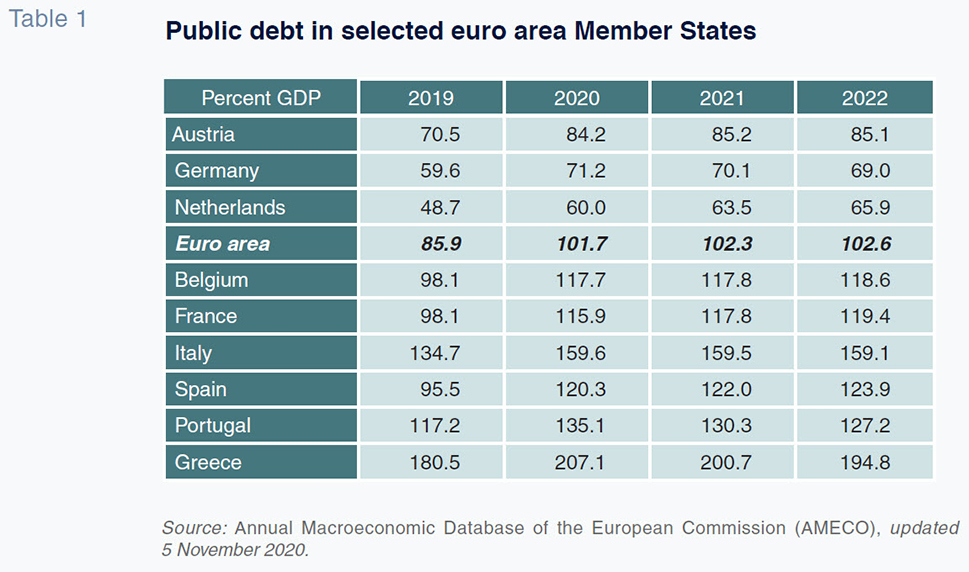

[1] That is not what happened in response to the pandemic. Instead, debt levels rose dramatically across the European Union, even in those countries that were already above the reference value. Moreover, the European Commission estimated in its November 2020 forecasts that these debt levels would remain high for at least the next two years (Table 1).

This increase in public debts cannot continue indefinitely. Indeed, the European Fiscal Board conducted a review of Member State fiscal positions in the summer of 2020. The questions it asked were whether the change in fiscal postures was sustainable over the medium-term and when it would be appropriate to consider deactivating the general escape clause. What the European Fiscal Board reported was unexpected. The ‘six pack’ legislation has clear criteria for activating the general escape clause but no criteria for when the general escape clause should be deactivated (European Fiscal Board, 2020a). This omission does not mean the clause should remain in effect indefinitely; what it implies is that any decision to deactivate the general escape clause will be political insofar as the timing is at the discretion of the Council – presumably on recommendation from the Commission. That said, the European Fiscal Board was clear that deactivating the clause in 2020 would be premature. Instead, it anticipated that a conversation about returning to the normal fiscal rules would start in 2021 with an eye to budgeting for 2022 (European Fiscal Board, 2020b).

The challenge that such a conversation will bring would necessarily focus on the pace of adjustment in public debt levels. The Commission estimates that the differential across the euro area will be greater than 40 percent of GDP. Starting an average fiscal correction worth roughly two percent of GDP each year in 2022 would slow down the pace of any economic recovery from the pandemic. More importantly, the fiscal effort will not be evenly distributed. The differential for Spain and Portugal will be greater than 60 percent of GDP, for Italy it will be roughly 100 percent, and for Greece it will be greater than 130 percent. It is unrealistic to believe that the governments of these countries will be able to reduce their public debt by an average of five percent (or one twentieth) of these amounts each year for two decades starting in 2022. That is why Commissioner Gentiloni argues that the rules will have to be revisited. The alternative would be to see most of Southern Europe placed into the ‘excessive deficit’ procedure on the basis of their need to reduce their public debts –with all that entails in terms of Commission oversight over national policymaking– for the foreseeable future. It is hard to imagine that such a situation would be politically sustainable for any country, but particularly for those that suffered so heavily during the last crisis.

Returning to ‘normal’

The main reason for considering a deactivation of the general escape clause is medium-term debt sustainability. At the moment, that does not seem to be a pressing concern. Although debt levels are high as a share of national output, interest rates are at historic lows (Bahceli, 2020). In December 2020, for example, harmonized long-term interest rate data from the European Central Bank show the governments of Spain and Portugal paying very close to zero on their ten-year bonds in terms of yield to maturity; the Greek and Italian governments pay more, with ten-year bond yields at roughly 0.6 percent, but such numbers are close enough to zero to make even very large volumes of public debt appear sustainable.

If anything, the nominal growth rate of GDP is the only variable that matters in such a context. So long as that nominal growth rate is positive there is little cause to worry about medium-term debt sustainability. This suggests that efforts to spur growth (or even just a positive rate of price inflation) should hold priority over fiscal consolidation even in highly indebted countries. Given that inflation rates are negative in much of the euro area –and stably so (Eurostat, 2021)– it is easier to make the case for macroeconomic stimulus than for macroeconomic consolidation. This is particularly true in Southern Europe, where inflation rates last December were negative, particularly in Spain (-0.6 percent) and Greece (-2.4 percent).

The problem comes from the policies which underpin the current low interest rate environment. Member State governments were not alone in trying to blunt the impact of the pandemic on economic performance. The European Central Bank (ECB) also contributed with a succession of measures announced in March, June, and December 2020 to ensure economic actors had ample access to liquidity. These measures included an unprecedented expansion of the ECB’s bond purchases – going beyond the 20 billion euros of net monthly purchases promised in September 2019, before the pandemic, with the addition of 100 billion euros in routine asset purchases and up to 1.85 trillion euros in purchases as part of a pandemic emergency program. (By end December 2020, the ECB had spent just over 750 billion euros of that figure).

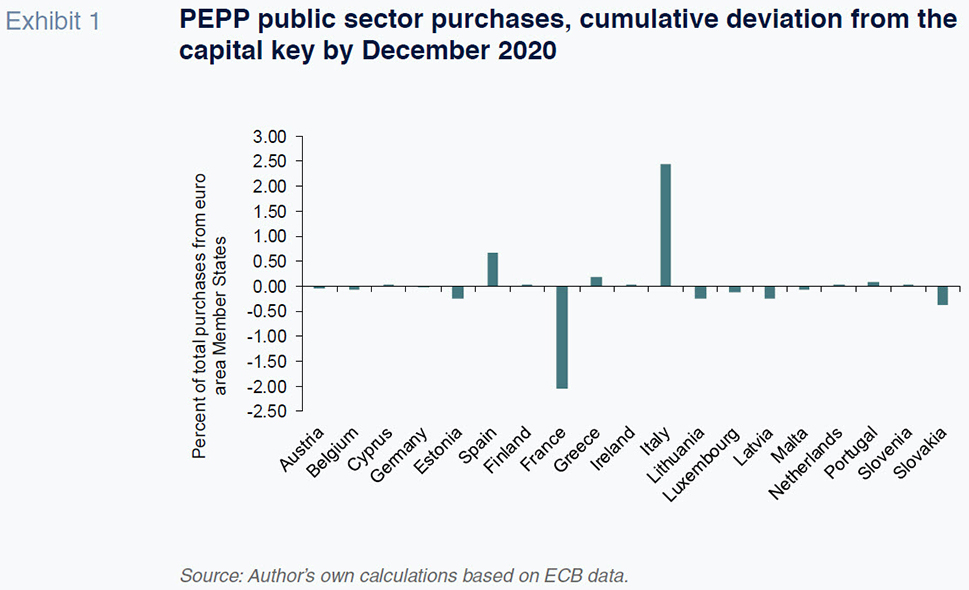

Importantly, those pandemic emergency purchases do not have to be proportionate across countries except across the life of the program. As such, the ECB can concentrate on propping up the prices of sovereign debt issued by specific governments for long periods. This flexibility is necessary to ensure the continuous functioning of the monetary transmission mechanism (Lane, 2020a and 2020b). Nevertheless, the result is that ECB holdings under this pandemic emergency purchase program skew heavily toward sovereign debt issued by governments in Southern Europe – Italy and Spain, in particular. This disproportionality can be seen in Exhibit 1, which shows the difference between the distribution of cumulative public sector purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase program across euro area Member States and their respective contributions to the capital base of the ECB (in percentage terms as a share of the total euro area contribution).

This skew in the ECB’s sovereign debt holdings is one reason for concern about the level of indebtedness. If it is true that ECB purchases make large volumes of sovereign debt more sustainable, it is also true that the existence of such large debt levels makes it more difficult for the ECB to wind up its pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP) or shrink down its asset portfolio even as those assets reach maturity. That is why ECB President Christine Lagarde (2020) is careful to mention that any ‘future roll-off of the PEPP portfolio will be managed to avoid interference with the appropriate monetary policy stance.’ The ECB must ensure that efforts to reduce its holdings of public sector assets do not impinge on the functioning of the monetary transmission mechanism by triggering a rapid fall in the price of sovereign debt across the southern countries of the euro area.

The ECB cannot continue to purchase sovereign debt indefinitely, even if only to replace maturing assets on its portfolio. The German Constitutional Court underscored this point in its May 5th, 2020, ruling on the ECB’s public sector purchase program. That ruling did not cover the PEPP explicitly, but the logic of the argument remains the same (Jones, 2020a). As a result, voices within the ECB’s Governing Council have begun to express concerns about the longer-term implications of the pandemic emergency purchase program both in terms of the legitimacy of their policy actions and in terms of their longer-term implications. Although there is broad agreement among Governing Council members during their December 2020 monetary policy deliberations that: ‘the PEPP [is] … the cornerstone of the … monetary policy package … attention was drawn to possible constraints on and side effects of additional purchases, such as the risks of moral hazard, fiscal dominance and distorted market functioning’ (ECB, 2021).

The challenge is to balance the need for active fiscal stimulus in the short-term with the requirements for fiscal sustainability in the medium-term. Those governments facing less daunting fiscal consolidation efforts after the pandemic –like the Dutch government– see the procedures outlined in the ‘six pack’ as the best route to achieving that balance. Therefore, they advocate a quick return to the guidelines for fiscal consolidation that were agreed in 2011. This is not an argument for austerity. It is an argument for recovering quickly from this crisis to prepare better for the next one. It is also an argument for strengthening fiscal positions across the euro area sufficiently to make it possible for the ECB to reduce the size of its asset portfolio without creating unnecessary market disruptions. For advocates of this position, concerns that enforcement of the fiscal rules would be politically unsustainable are more than offset by concerns that a failure to enforce the rules would be unsustainable both in fiscal terms and in terms of ECB monetary policy – particularly if the euro area faces another major economic shock in the not-too-distant future.

Countervailing factors

Recent political developments in Europe push in both directions, toward more active use of fiscal instruments in responding to the pandemic and toward greater caution about medium-term debt sustainability. The push for more active use can be found initially in the April 23rd, 2020, agreement to create credit facilities to support employment and unemployment benefits via the European Commission, small- and medium-sized enterprises by the European Central Bank, and national health services by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Such efforts culminated in the European Council’s July 21st agreement on a new recovery and resilience facility as part of the larger ‘Next Generation EU’ package. At the same time, however, the governments of the euro area have continued to push for a reform of the European Stability Mechanism to give that institution a more prominent role in overseeing the requirements for fiscal consolidation as outlined in the ‘six pack’. Those reforms will be implemented in February 2021.

The tension between these two efforts was immediately apparent, particularly with respect to the creation of a pandemic-related credit facility within the ESM. Proponents of the facility insisted that the ESM was created precisely to help governments access credit markets in moments of distress. Opponents expressed concern about having the ESM play a role in shaping and enforcing fiscal consolidation programs. The compromise was to limit any conditions on borrowing to a single requirement that funds be used to support health and health-related expenses arising from the pandemic. Even with those reassurances, however, no government has accessed the 240 billion euro facility to support spending on health care even during a very painful second wave of the pandemic. By contrast, the European Commission approved requests for just over 90 billion euros of is 100 billion euro facility to support employment protection and unemployment benefits by December 2020, and it disbursed just under 40 billion euros of the loans it approved (Jones, 2021).

Next Generation EU was also controversial, albeit less immediately. The July 21st agreement to create the new program was an important demonstration of European solidarity. The 750 billion euro fund includes up to 390 billion euros in expenditures that will be jointly financed through bonds issued by the European Commission to be repaid through taxes levied across the European Union. Such joint fiscal effort is unprecedented. The fund also includes 360 billion euros in back-to-back lending to the Member States as part of the recovery and resilience facility. These loans will also be financed initially through bonds issued by the European Commission, but they will be repaid by national fiscal authorities in much the same way that national authorities are responsible for repaying loans taken out as part of the Commission’s facility to support employment protection and unemployment benefits. Hence, such loans count as Member State public debt (Fubini, 2021).

The controversy over loans for the recovery and resilience facility arose initially in response to the powers given to the European Commission to monitor the economic policies of those governments that receive assistance. These powers are expansive. The Commission has the authority to ensure compliance with country-specific recommendations for institutional reforms and medium-term fiscal sustainability in addition to overseeing how any funds received by the Member States are spent. Governments that fail to comply with European guidelines may face a suspension of funding via the recovery and resilience facility. Hence, many Member State governments have opted not to take up additional loans from the European Commission, particularly when they can access private capital markets at similar or even better financing terms. For example, the Spanish and Portuguese governments announced that they would not borrow under the new facility in October 2020 (Pérez, 2020).

What is unclear is whether Member State governments will replace borrowing they could access from the Commission with borrowing at the national level. Such loans would not come with conditions attached, but they would still count against national debt stocks – implying a larger future adjustment once the general escape clause is deactivated. By contrast, the grants awarded via the recovery and resilience facility do not count as national public debt. This makes the grants attractive despite any conditions attached by the European Commission. Even governments that refuse the loan portion of the new facility are likely to bid for access to their grant allocations.

The accounting treatment of European grants under the recovery and resilience facility is not without controversy – particularly as it impacts on medium-term fiscal sustainability. The German Bundesbank, for example, argues that failure to count European grants as national debt obscures the fact that national governments are ultimately responsible to repay European Union borrowing (Bundesbank, 2020). The European Commission is unlikely to change the accounting treatment of EU debt as a result of this objection. What matters more is whether and how those governments that are less enthusiastic about the European Union’s new recovery program and more concerned about preparing for the next crisis perceive the Bundesbank’s arguments.

Recent reforms to the European Stability Mechanism highlight that concern for medium-term fiscal sustainability as well. Those reforms were agreed in December 2019, prior to the pandemic, even if the last obstacles to ratification took another year to clear. They give the ESM authority to participate in macroeconomic policy coordination in normal times and with a specific aim to reinforce efforts at fiscal consolidation. They also create a new precautionary credit facility that Member State governments can access provided they meet the criteria for fiscal sustainability as set out in the ‘six pack’ legislation. Indeed, the reference values are spelled out explicitly in an annex to the new ESM Treaty – including the necessary path for fiscal adjustment (ESM, 2019). By implication, it would not be sufficient to change the legislative framework set out in the ‘six pack’ to modify that fiscal adjustment path; it would also be necessary to modify this ESM Treaty annex. Reopening that Treaty so soon after it has been agreed would be challenging, which makes any reform of this debt adjustment path unlikely.

Governments that do not meet the fiscal criteria set out in the ESM Treaty annex are ineligible to receive precautionary support and so must apply for an ‘enhanced conditions credit line’ should they require financial assistance. Such ‘conditions’ are what make borrowing from the ESM unattractive for Member State governments. As a result, the Member States have a strong incentive to pay attention to the formal requirements for medium-term financial stability as set out in the ‘six pack’. Those incentives operate even while the general escape clause is activated. Once that clause is deactivated, the incentives to comply with European fiscal norms increase under the new Treaty.

Implications

The conversation about deactivating the general escape clause will be difficult. If the economic consequences of the pandemic continue to worsen, it is possible that conversation will be delayed. At some point, however, the debate will have to take place. Moreover, governments across Europe are well-aware of the implications, as are the ECB and the European Commission. So long as the criteria for medium-term fiscal sustainability set out in the ‘six pack’ and repeated as the eligibility requirements for ESM precautionary lending remain unchanged, the future deactivation of the general escape clause will weigh on Member State fiscal policy. Those governments that have relatively low debt-to-GDP ratios will prepare to consolidate those positions; those governments that face daunting fiscal adjustment challenges will think twice before undertaking additional public borrowing. Such attitudes are unlikely to prevent governments from providing exceptional short-term assistance to firms and households suffering from the pandemic, but they are likely to limit enthusiasm for longer-term investment programs – even when those programs are financed initially with funds raised by the European Commission.

This prognosis is not good for the countries of Southern Europe. Those countries were hit hard by the last crisis and have great need for sustained, productive investment. Spain and Italy also suffered disproportionately from the initial onset of the pandemic; as a result, both countries will require significant resources to repair the damage done to households and businesses. Doing so while managing a major fiscal consolidation effort in line with the requirements set out in the ‘six pack’ will be a daunting if not impossible task. Should such efforts extend beyond the ECB’s ability to maintain its accommodative monetary policy strategy, that challenge could increase dramatically.

The question is whether there is a compromise between reforming the rules for fiscal accommodation or trying to return to those rules prematurely. The ‘six pack’ provides language for Member States to be given consideration when they face exceptional circumstances and yet that language is ambiguous. The political effort would be to apply that language to the longer-term challenges faced by the countries of Southern European. Nevertheless, a creative reinterpretation of the existing legislation is likely to be better than the alternatives.

Notes

[1] This language is found in article 1a of Regulation (EC) 1467/97 as amended.

References

ANSA (2020). Stability Pact Must Be Revised Says Gentiloni. ANSAen Latest News, 9 December.

BAHCELI, Y. (2020). Analysis: Money for Nothing – Portugal, Spain Borrow More, Pay Less. Reuters, 3 December.

BUNDESBANK (2020). The Informative Value of National Fiscal Indicators in Respect of Debt at the European Level. Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report (December), pp. 37-47.

EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK (2021). Meeting of 9-10 December 2020. Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 14 January.

EUROPEAN FISCAL BOARD (2020a). Assessment of the Fiscal Stance Appropriate for the Euro Area in 2021. Brussels: Secretariat of the European Fiscal Board, European Commission, 1 July.

— (2020b). Annual Report, 2020. Secretariat of the European Fiscal Board. Brussels: European Commission, 28 September.

EUROPEAN STABILITY MECHANISM (2019). Annex III: Eligibility Criteria for ESM Precautionary Financial Assistance. Luxembourg: European Stability Mechanism (6 December).

EUROSTAT (2021). Annual Inflation Rates Stable at -0.3% in the Euro Area. NewsRelease, EuroIndicators, 12/2021, 20 January.

FUBINI, F. (2021). Recovery fund, altolà di Gualtieri sui conti publici. Corriere della Sera, 2 January.

JONES, E. (2020a). COVID-19 and the EU Economy: Try Again, Fail Better. Survival, 62:4, pp. 81-100.

— (2020b). When and How to Deactivate the SGP General Escape Clause. Brussels: Economic Governance Support Unit, Directorate General for Internal Policies, European Parliament, PE 651.378, November.

— (2021). Did the EU’s Crisis Response Meet the Moment? Current History, 120, forthcoming.

LAGARDE, C. (2020). Press Conference, Introductory Statement. Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 10 December.

LANE, P. R. (2020a).‘The Monetary Policy Package: An Analytic Framework. ECB Blog, 13 March.

— (2020b). Expanding the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program. ECB Blog, 5 June.

PÉREZ, C. (2020). Why Spain Will Not Ask for €70 Billion of Its Share of the EU Recovery Fund. El País, 19 October.

Erik Jones. Professor of European Studies and International Political Economy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies