The Spanish economy in 2017 and the outlook for 2018

Global economic growth is exceeding expectations and the outlook remains positive for 2018. In this context, Spain’s economy should stay on the solid and balanced growth path recorded in 2017.

Abstract: The international economic environment has improved substantially virtually across the board. This constructive global backdrop has helped sustain the positive momentum of the Spanish economy in 2017. In 2018, growth is forecast at a solid, albeit more moderate, 2.6%, with 0.2-0.3% of the deceleration attributable to political tensions in Catalonia. Unlike previous episodes of growth in Spain, external accounts are not showing signs of tensions and the recovery is not expected to fuel inflation. Certain key imbalances are being corrected, with notable improvements in employment figures and deficit reduction in line with official targets. Nevertheless, the main challenges for the Spanish economy in the coming years remain public debt and the labour market, where long-term strategies from the government will be needed. Going forward, the main assumptions underpinning our forecasts are more likely to surprise on the upside. However, there are outstanding, important downside risks, such as a continuation of tensions in Catalonia and a faster than anticipated withdrawal of ECB stimulus.

The international environment

The international climate has improved substantially. The IMF has revised its 2017 estimates for global growth upwards. The Fund is currently looking for global GDP growth of 3.6% in 2017, which is up 0.2pp from the previous forecast.

The US economy remains one of the main growth engines, refuting all doubts about the sustainability of its growth. US unemployment is close to all-time lows, albeit apparently without impinging upon the momentum in growth.

Elsewhere, the risk of the credit bubble bursting in China has not materialised. The Chinese economy is managing to balance its economic model, reinforcing its internal growth drivers and reducing dependence on exports. Growth, albeit somewhat slower, remains robust. Moreover, some of the larger emerging markets that were looking weak, such as Argentina, Brazil and Russia, are staging a recovery. Virtually all the developing economies have come out of recession.

The biggest surprise across the analyst community has been the positive momentum displayed by the European economy. The core eurozone economies, especially Germany, despite the scarcity of labour starting to become evident in some of its most buoyant sectors, continue to grow. Growth has reached France and some of the countries that not long ago were in recession (Greece, Italy and Portugal). The non-eurozone economies are also performing well. Specifically, the British economy continues to grow despite the uncertainty surrounding its exit from the European Union. It would appear that the markets are pricing in a soft Brexit.

The outlook for 2018 is positive. The IMF is expecting another 0.1pp of global growth: 3.7%. In the US, some analysts think the tax reforms will give the economy a boost in the short term. Others believe the tax cuts will aggravate an already tight labour market, while prompting growth in the public deficit and a response from the Federal Reserve; however, in all likelihood, these tensions will not fully materialise until 2019. It is estimated that the major emerging economies will maintain current or even higher levels of growth, particularly Latin America, India and the main natural resource-rich countries.

The European economy is also expected to post vigorous growth. In the eurozone, Funcas is forecasting GDP growth of 2.3%, the same as in 2017. In a climate of growing demand, commodity prices, particularly gas, oil and metals prices, are expected to come under pressure. Elsewhere, it is probable that the central banks will continued to roll back the monetary stimulus measures adopted in response to the financial crisis. The Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates on a staggered basis, while the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan are likely to pare back their debt buyback programmes. In all, monetary conditions look set to be relatively accommodating once again this year.

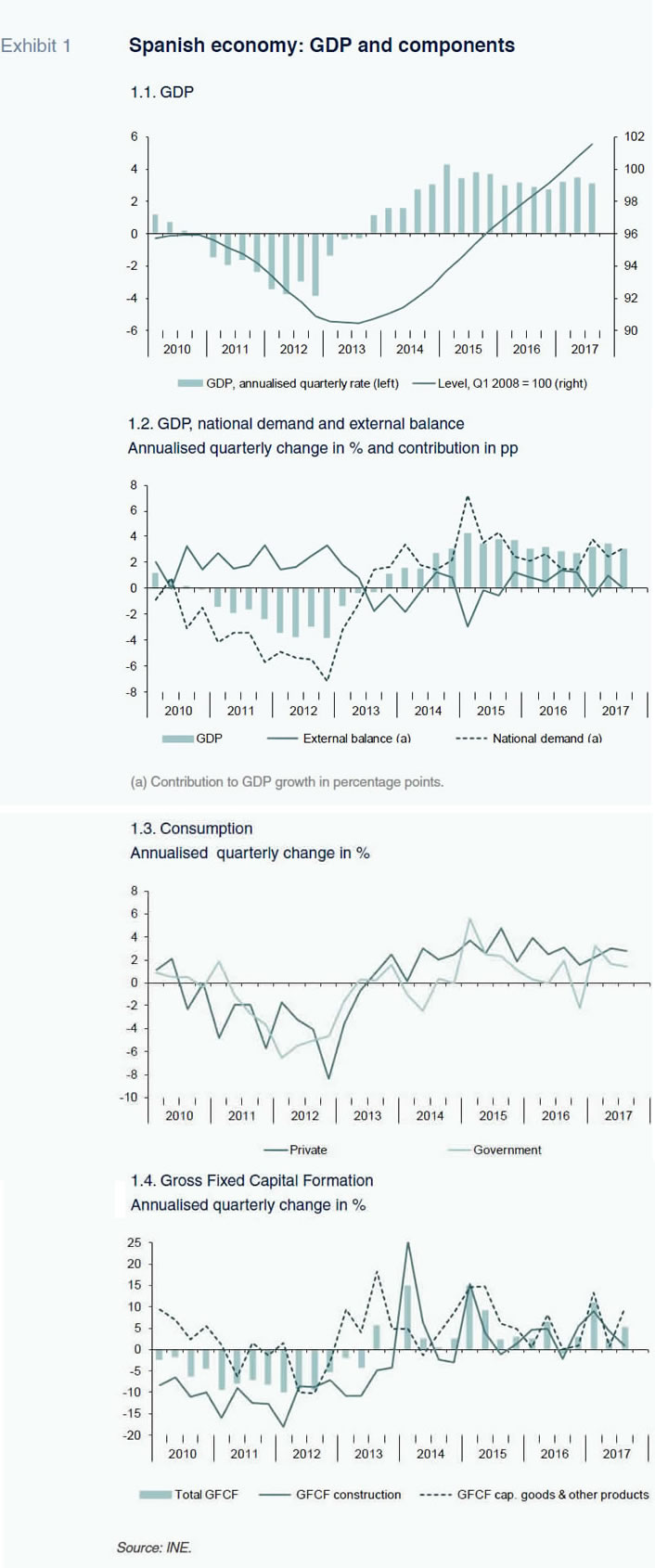

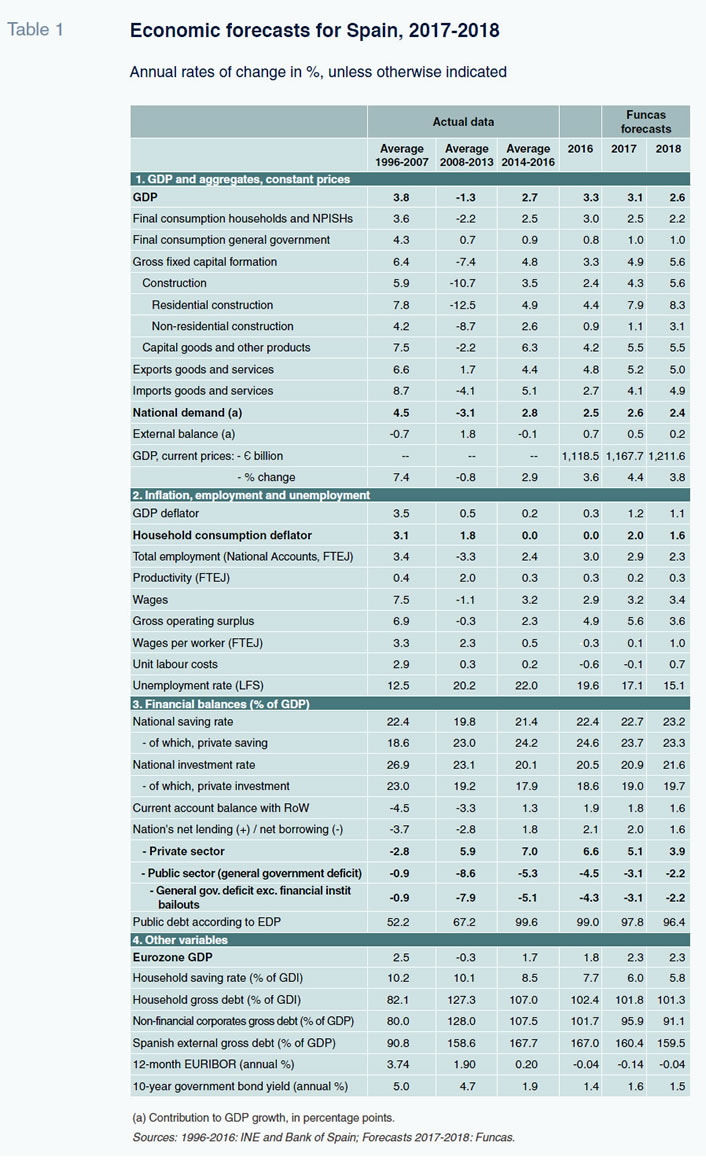

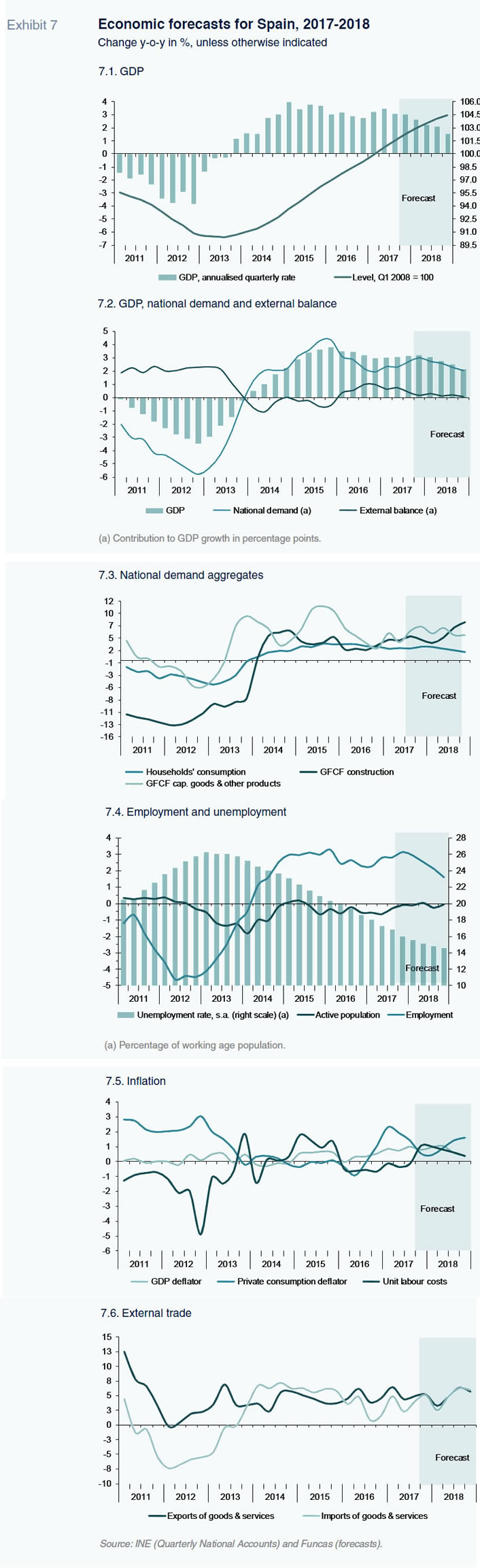

The Spanish economy in 2017Although not all the indicators are in for the fourth quarter yet, the Spanish economy is expected to grow by 3.1% in 2017. Assuming this outcome, real annual GDP will have recovered the high of 2008 in 2017 (in nominal terms this peak was reached last year) (Exhibit 1.1). Growth will come in 0.2pp shy of the 2016 reading, albeit substantially higher than what was expected at the end of that year, when consensus forecasts pointed to growth of just 2.4%. The higher than forecast growth is the result of more dynamic growth in national demand than was originally expected, specifically in construction and public spending, as well as a higher contribution by foreign demand, thanks to lower than anticipated growth in imports (Exhibit 1.2). The contribution by the foreign sector, albeit higher than expected, was nevertheless lower than in 2016 and is the main factor behind the slowdown in GDP growth year-on-year in 2017.

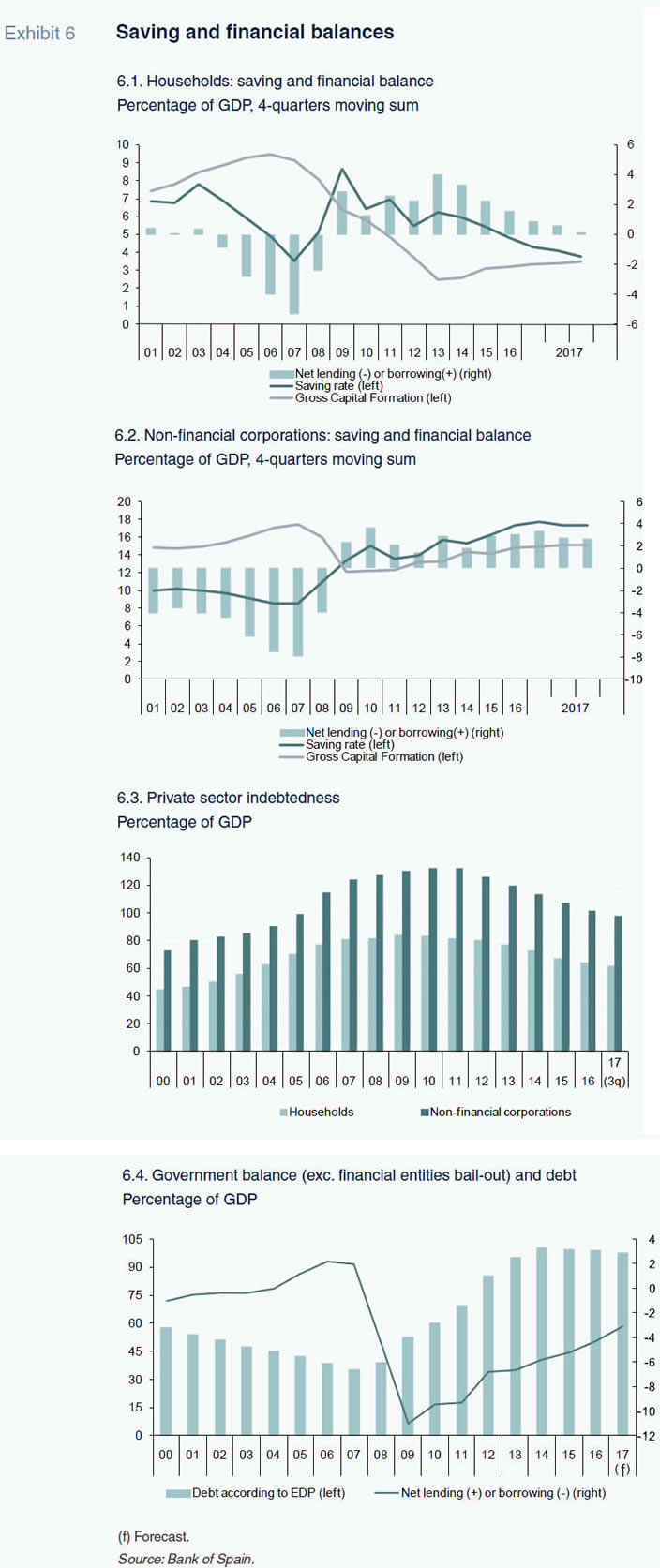

Although growth in household consumption slowed in real terms in 2017 (Exhibit 1.3), in nominal terms it accelerated considerably, from 2.9% to around 4.5%, due to the uptick in inflation. The growth in nominal spending outpaced the growth in disposable household income, prompting a sharp drop in the savings rate. In short, Spain’s households have reacted to the increased cost of their shopping baskets by depleting their savings and, to a lesser extent, by purchasing fewer goods and services.

Despite the growth notched up since the start of the recovery, in 2017 annual household consumption was still 3.6% short of the record level of 2007. Growth in public spending was similar in 2017 to that observed in 2016 in both real and nominal terms.

Growth in investment in capital goods accelerated year-on-year, albeit largely due to the transfer of a portion thereof from the last quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2017 due to changes to corporate income tax regulations (Exhibit 1.4). This component of demand has grown the most since the recovery got underway (+30% from the low of 2012) and is, along with public spending, the only component of national demand that stands above its pre-crisis level. It is being driven by the recovery in corporate profits and low interest rates.

Investment in house construction registered very intense growth. However, it is worth pointing out that in the wake of the sharp contraction suffered during the crisis, investment volumes remain at only 55% of the high of 2007. Real estate activity remained particularly buoyant, marked by annual growth in house transactions of 15% and growth in average house prices of almost 6%. Investment in other types of building work remained weak, however, due to the contraction in public works (government investment contracted by 0.7% up to the third quarter of 2017).

Exports of goods and services accelerated against the backdrop of revitalised global trade, which grew, according to IMF estimates, by more than global GDP for the first time since 2014. Growth in imports similarly accelerated in nominal terms in 2017 as a whole but by less than exports in real terms (note however that customs figures point to a recent trend of slightly higher growth in imports relative to exports) (Exhibit 2.1). This acceleration is partly attributable to the recovery in the purchase of energy goods, which fell considerably in 2016.

The growth in imports was however smaller than expected for the second year in a row, despite the fact that end demand was stronger than forecast, which would appear to confirm a certain decrease in their elasticity. The growth in imports at current prices outpaced that in exports, due mostly to the increase in oil prices (although growth in non-energy import prices also outpaced non-energy export prices).

The sector spearheading growth in 2017 was construction, followed by the manufacturing industry. The tourism industry also registered noteworthy growth, with tourist arrivals increasing by 9%, which is very close to the record high of 10% in 2016. Growth in total expenditure by tourists even topped that of 2016, thanks to the growth in average expenditure per tourist.

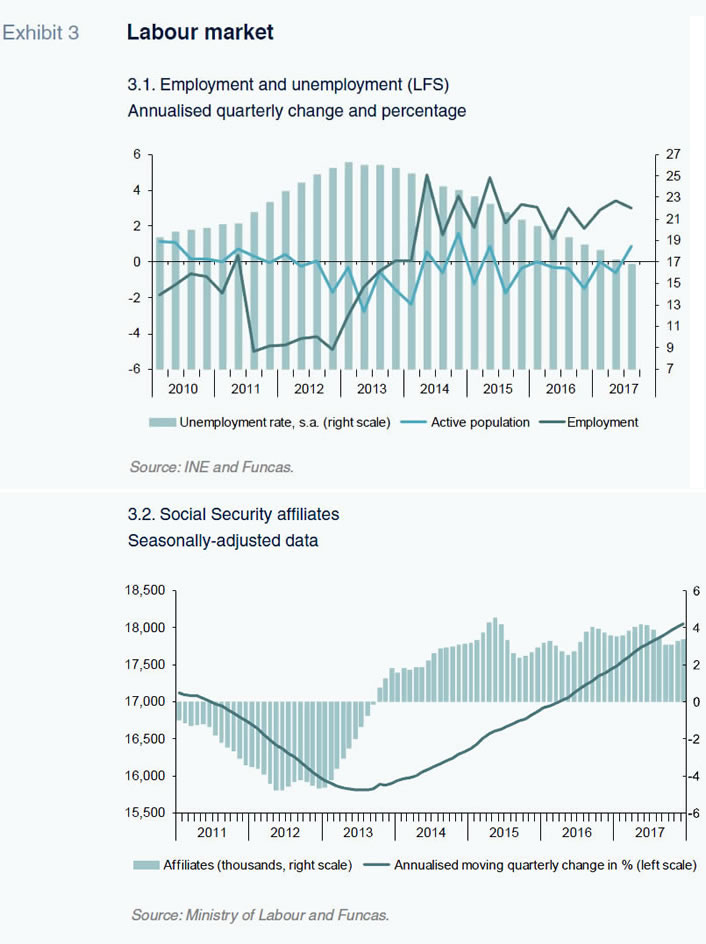

The growth in employment − measured in terms of full-time equivalent positions − is estimated at 2.9%. In terms of Social Security affiliates, the growth in 2017 was 3.6%, which is equivalent to 626,000 new affiliates (Exhibit 3.2), the best performance in the series, which dates to 2001, with the exception of the increases registered in 2005 and 2006 due to the legalisation of undocumented workers. The number of affiliates (annual average) reached 18.2 million, the highest figure since 2008, implying the recovery of two-thirds of the jobs lost during the crisis. Affiliation numbers registered the strongest growth in the construction sector, although the growth in the manufacturing industry affiliates is similarly notable on account of its lack of precedence in the series: +3.1%. Most of the jobs created were temporary in nature.

According to the labour force survey, growth in employment was somewhat lower than that indicated in the national accounts and Social Security affiliate numbers. Until the third quarter (the latest figures available), growth was trending at 2.6% year-on-year (Exhibit 3.1). The drop in unemployment was a little smaller than the increase in employment due to the decrease in the active population which in turn was driven mainly by the drop in the participation rate and, to a lesser extent, in the working-age population.

The downtrend in the latter, underway since 2010, eased significantly in 2017, reflecting an unexpected turnaround in the population aged between 16 and 24, which registered year-on-year growth, at least until the third quarter, for the first time since 1992. The average annual rate of unemployment is estimated at 17.1%, down 2.5pp from 2016.

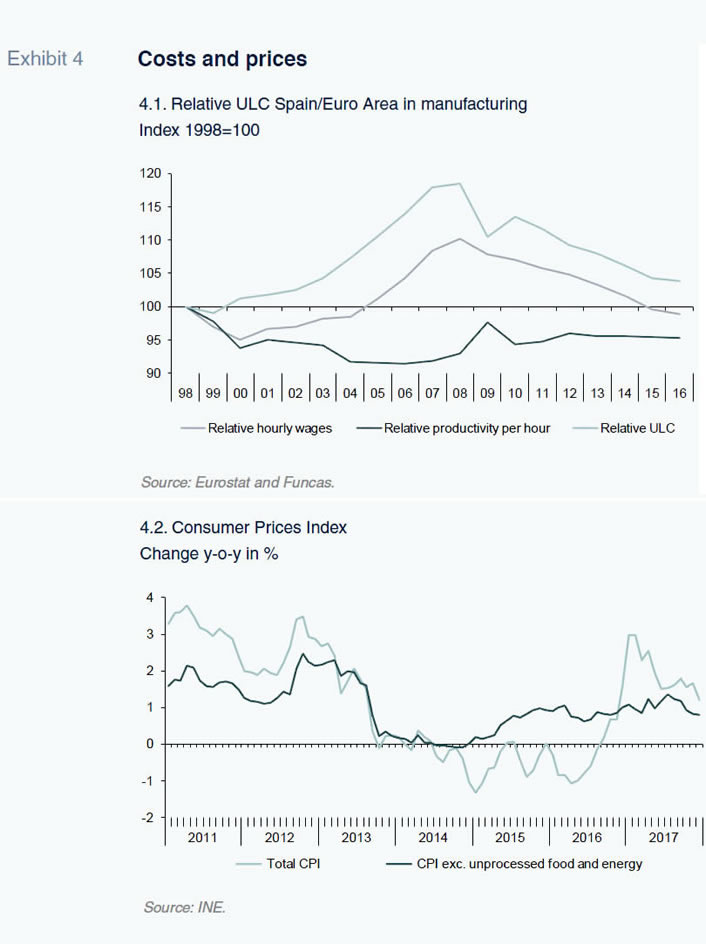

Average remuneration per wage-earner increased by 0.1%, according to the national accounts, which is considerably below the 1.4% agreed via collective bargaining. The growth in productivity is estimated at 0.2%, implying that unit labour costs across the economy as a whole fell by 0.1%. In the manufacturing sector, however, unit labour costs increased slightly for the first time since 2009.

The average annual rate of inflation was 2%, compared to -0.2% in 2016 (Exhibit 4.2). The uptick was driven by the higher cost of energy products, in turn shaped by the rise in oil prices which, in euros, were 22% higher on average in 2017 than in 2016. To a lesser extent, the headline rate was also influenced by the rate of core inflation which at an annual average of 1.1% nevertheless remained very moderate. The gap with respect to the eurozone average turned positive, i.e., unfavourable for Spain, after three years in negative territory. This is because when energy product prices rise, they go up by proportionately more in Spain than in the rest of Europe on account of the smaller weight of taxes in end prices. The gap in core inflation with respect to the eurozone average was negligible.

The current account surplus stood at 14.1 billion euros to October, compared to 15.2 billion euros in the same period of 2016. This slight decrease is attributable to the increase in the goods trade deficit, driven above all by the rise in oil prices. The services trade surplus widened, while the income deficit narrowed year-on-year (Exhibit 2.2). The current account surplus is expected to come in at 1.8% of GDP, 0.1pp less than in 2016.

The fiscal deficit to September stood at 17.1 billion euros, 1.5% of annual GDP, down from 30.0 billion euros in September 2017. The reduction is the result of growth in revenues compared to virtual stabilisation in expenditure. Tax receipts from VAT, personal income tax and social security contributions stand out. In light of these results, and despite adverse seasonality in the latter months of the year, Spain is expected to deliver on its fiscal deficit target of 3.1% in 2017 (Exhibit 6.4). Debt as a percentage of GDP fell slightly. As for the Social Security system, it is worth highlighting the fact that the growth in revenue from contributions was higher than the growth in pension outlays, driving a reduction in its deficit.

Spanish households’ gross disposable income (GDI) increased by 1.9% year-on-year in the first nine months of 2017, whereas nominal final consumption expenditure was 4.3% higher. This implies a sharp erosion of savings, which dropped to 4% of GDI, compared to 6.2% in September of 2016. As a result, in the first nine months of the year, the household sector registered a net borrowing requirement − i.e., their savings were insufficient to finance their investments − for the first time since 2008. However, due to positive seasonality in the last quarter of the year, it is likely that the end result for the year will be one of financial surplus, albeit very tight compared to the levels observed since the start of the crisis.

The amount of new credit extended to households to November of last year (excluding debt refinancing activity) increased by 17%, with house mortgages and consumer credit both registering growth. However, despite notching up four straight years of growth, the volume of new credit extended to households was barely a third of the amount being granted at the end of the last period of growth, such that repayments are still outstripping new loans. As a result, household borrowings have continued to come down in both absolute and relative terms, although at a considerably slower pace than in prior years, which is a reflection of their diminishing financial surplus. As of the third quarter of last year (the last for which there is available data), household borrowings accounted for 100.3% of their GDI, down from 103.4% a year earlier (Exhibit 6.3).

Spain’s non-financial corporations saw their cumulate net lending capacity narrow slightly year-on-year in the first nine months of the year due to higher growth in their investments relative to their income (Exhibit 6.2). Growth in new loans to enterprises also rose in 2017, especially loans to SMEs, despite which their borrowings, according to the financial accounts, continued to fall in absolute and relative terms and stood at 98.1% of GDP as of September, 5.5pp down from a year earlier.

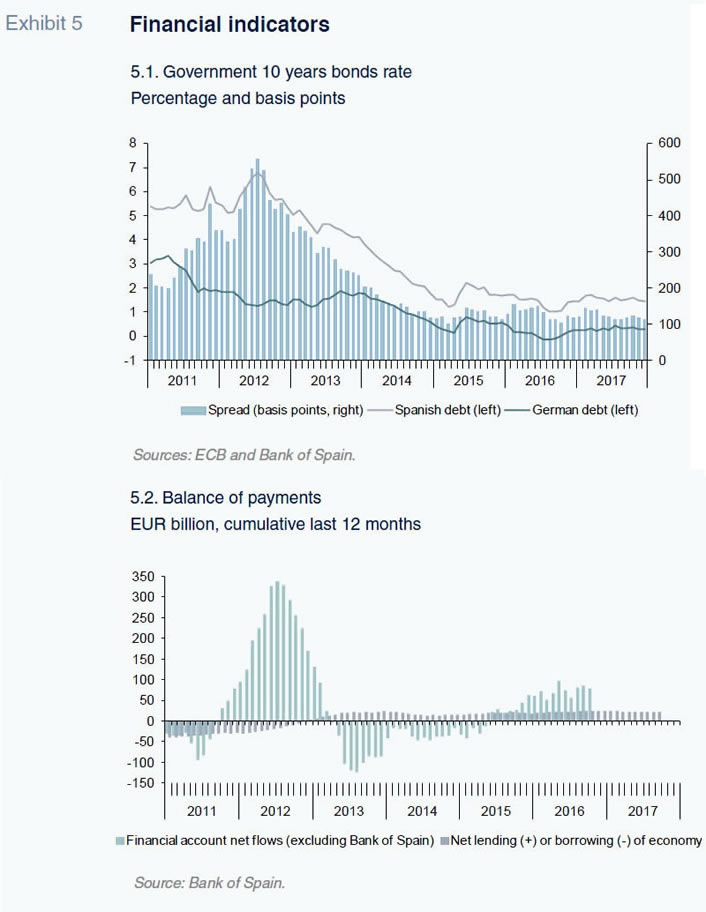

Against the backdrop of ultra-lax monetary policy, with the interest rate on the ECB’s deposit facilities in negative territory and with the monetary authority continuing to repurchase long-term debt securities, the interest rate environment remained very propitious for economic activity in 2017. The short-term rate (3-month Euribor) was stable all year at -0.33%, while 12-month Euribor, which had already been in negative territory in 2016, continued its slide throughout the year, ending 2017 at -0.19%. As for 10-year bond yields, there was no major movement in 2017. In the initial months of the year, the yield stood at 1.70%, from where it went on to fluctuate around the 1.55% mark, falling somewhat towards the end of the year to 1.44%. The annual average was only slightly higher than that of 2016. The risk premium relative to the German sovereign bond narrowed slightly, from 140 basis points in the first months of the year to 110 in December, a trend interrupted in October when it increased a little as a result of the Catalan political tensions, going on to return to the pre-crisis levels (Exhibit 5.1).

In short, 2017 was marked by continued solid and balanced growth, driven significantly by investment, in both capital goods and construction, and the foreign sector. On the downside, however, it is worth highlighting the sharp drop in household savings and their net lending capacity, curbing the potential for growth in consumer spending in the near term and foreshadowing the end of this sector’s deleveraging process.

Outlook for 2018In 2018, the economy is expected to grow by 2.6%, a healthy pace, albeit slower than in the past three years. The slowdown reflects reduced expected momentum in domestic demand (estimated to grow by 0.2pp less in 2017), as well as a smaller contribution by foreign demand (Table 1).

The trend in national demand is in turn explained by the forecast slowdown in private consumption (Exhibit 7.3), which is expected to increase in line with household disposable income, implying a slight reduction in the savings rate, which is expected to hit a series low. In prior years, consumption had been growing faster than disposable income, as confidence rose, prompting households to dip into the safety nets they had built up during the worst years of crisis.

As for the other drivers of national demand, growth in public spending is expected to ease, while gross fixed capital formation is projected to take off, thanks to the improved outlook for residential investments. Growth in investment in capital goods and other products, meanwhile, should remain dynamic, underpinned by solid corporate profits and low interest rates.

The contribution by the foreign sector should be positive, albeit smaller than in 2017. Exports of goods and non-tourism services are expected to continue to gain market share, leveraging the buoyancy of the global economy and strong competitive positioning of Spanish firms. Revenue from tourism should also increase, although at a slower rate as some of the most popular destinations are becoming saturated. The recovery in imports is set to continue, in line with estimated elasticity (Exhibit 7.6).

Despite the fact that the economy is entering its fourth year of sustained growth, the foreign accounts are not showing any signs of tension. As has been the case since the start of the recovery, Spain will once again register a considerable current account surplus. The current expansion, marked by a combination of high growth and a sizeable surplus, is unprecedented in the country’s recent economic history.

Nor is the recovery expected to fuel inflation, in contrast to that observed in prior periods of growth. The private consumption deflator is expected to be 1.6%, which is clearly below the threshold the ECB views as compatible with price stability. The growth in the GDP deflator − which reflects the trend in core inflation − will be even lower (Exhibit 7.5).

Certain key imbalances are in the process of correction. Employment should continue to register intense growth, albeit lower than in 2017. The forecasts point to the creation of more than 400,000 jobs (in national accounting terms, which measure employment on the basis of full-time equivalent positions). The unemployment rate could fall to 15.1% on average in 2018 and 14.6% in the fourth quarter, which would mark the lowest level since the end of 2008 (Exhibit 7.4).

The improvement in the job market, coupled with the increase in the minimum wage, should kick-start a rise in wages. Average remuneration per wage-earner is forecast to grow by 1%, which remains below the estimated rate of inflation. In light of the weak forecast increase in productivity, unit labour costs could increase for the first time in three years, albeit at a low annual rate of 0.7%, which is less than half the level the ECB is forecasting for the eurozone. As result, the Spanish economy should continue to gain competitiveness and recover virtually all of the ground lost since the introduction of the single currency.

The public deficit is also expected to come down, to 2.2% of GDP, shaped by moderate growth in public expenditure coupled with growth in revenue, in line with the economic dynamism. The economic recovery unfolding, in addition to Spain’s foreseeable release from the European excessive deficit procedure, should be reflected in the international credit ratings assigned to Spain’s sovereign bonds in the months to come.

Nevertheless, despite the favourable global economic climate, public borrowings and the job market will continue to be the main challenges facing the Spanish economy in the years to come. Aggregate borrowings at all levels of government should fall to 96.4% of GDP in 2018, just 1.4pp down from 2017.

The current ultra-lax monetary policy is facilitating public debt servicing. At the rates prevailing in 2012, before the start of the ECB’s debt security repurchase programme, the Spanish government (all levels) would have had to pay 16.66 billion euros more in interest than it did in 2017. The result would have been to wipe out the effort to cut the deficit: at 2012 rates, the public deficit would have been 4.6% in 2017, 0.1pp more than in 2016. It is unlikely that rates will return to the levels of 2012. However, the announced ‘normalisation’ of monetary conditions will push up the cost of servicing the public debt and, in the absence of a long-term strategy for reducing the debt burden, increase the country’s credit risk.

This strategy needs to contemplate specific measures for tackling the main budget mismatches, starting with the structural deficit in the pension system. There is a lag, due to demographic factors, between inert growth in expenditure on pension benefits and the revenue collected via social security contributions. Short-term, the formula for updating pension payments (+0.25% per annum as long as the system is in deficit) is helping to contain the deficit. However, this measure is translating into a loss of purchasing power and increase in poverty on the part of Spain’s pensioners, a situation that is not socially sustainable. On the revenue side, the various deductions being offered on the various classes of employment contracts are eroding the revenue base and are not necessarily proving efficient as a tool for stimulating hiring.

The job market, meanwhile, continues to suffer from two structural problems. First of all, the crisis has left a legacy of long-term unemployment that cannot be fixed by more economic growth. This issue requires specific measures targeted at helping to get these long-term job-seekers back to work. To get this done, the employment offices need to do a good job, while the government needs to design proactive policies. The good practices beginning to crop up in various regional governments are shining a light on the way forward. The state could induce these efforts, as governments in other countries with decentralised structures such as Germany, Canada and Switzerland are doing.

The precarious nature of many of the jobs being created is the other drag on the Spanish economy and social cohesion. Here the solution entails reforms that foster legal certainty, so that companies that have to downsize for legitimate economic or business reasons can do so availing of a faster procedure less exposed to random decision-making in the courts. The authorities also need to step up the effort to thwart hiring abuse (fake interns, self-employment and dependence claims and the arbitrary interruption of temporary contracts to avoid having to pay for holiday time off or maternity leaves, etc.). The idea is to minimise the hiring of interns and temporary workers when a business’s needs are stable. An agreement between the government, employers and unions on this much-needed area of reform would help to improve the productive model and ready the country for digital transformation.

Main risks

The forecasts have been articulated around three main assumptions. Firstly, as already mentioned, that the international environment will remain propitious. Secondly, that the current combination of macroeconomic policies (expansionary monetary policy and neutral fiscal policy) will continue. Lastly, the situation in Catalonia will gradually normalise. This implies that the Catalan economy will find its way back to the growth track from the second quarter. In 2018, the conflict is expected to erode Spanish GDP growth by between 0.2 and 0.3pp.

There is more upside than downside however. Recent indicators suggest that the world economy ended the year stronger than expected. The eurozone, which accounts for almost 60% of Spanish exports, is particularly dynamic, which could add a little to Spanish growth.

But there is also downside. Instability in the Middle East and tension between Saudi Arabia and Iran could push oil prices higher, which would have important repercussions for the Spanish economy. Domestically, the big question is what consequences the political crisis in Catalonia will have. If the crisis continues, the economy in this region could suffer by more than is currently being predicted. Moreover, this situation would reduce elbow room for undertaking new reforms and leave the economy more exposed to potential shocks, such as a faster than anticipated withdrawal of the ECB stimulus measures.

Raymond Torres and Maria Jesús Fernández. Economic Trends and Statistics Department, Funcas