Spain’s fiscal context: A regional perspective

While the Spanish general government deficit is forecast at 12.4% this year, the regional governments posted a surplus during the first eight months of the year. However, the regional governments’ finances will experience greater pressure in the following years, necessitating reform of both the regional financial system and Spain’s overall tax system.

Abstract: Spain entered 2020 in a complicated financial situation with the budget from 2019 having carried over and the reduction of the deficit having stalled at 3% of GDP. However, any fiscal consolidation effort was halted by the EU’s activation of the Stability and Growth Pact’s escape clause in light of the COVID-19 crisis in March. As a result of a collapse in tax revenue and increased spending, the Funcas’ consensus forecast anticipates that Spain will post a 12.4% deficit in 2020. In comparison to the central government, Spain’s regional governments have presented a surplus of 0.44% in the first eight months of the year. This is attributed to both the amount of tax revenue transferred and advanced by the central government to the regional governments. Looking forward, the crisis will have a differential impact on regional finances and it will be necessary to reform the regional financing system in tandem with an overhaul of the Spanish tax system to address the financial consequences of the health crisis.

And then COVID-19 came along [1]Spain began 2020 under a budget that had carried over from 2019 and a stalling deficit reduction-effort, with the structural deficit stagnant at 3% of GDP (Lago-Peñas, 2020). However, those concerns would become secondary in March. Compliance with the EU’s fiscal stability rules was deprioritised when, at the end of that same month, the European Commission and the Council of the European Union activated the general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). That decision occurred in tandem with Europe’s rapid, forceful, and coordinated response to the COVID-19 crisis. This action aligned with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which stated unequivocally that “high levels of public debt are not the most immediate risk. The near-term priority is to avoid a premature withdrawal of fiscal support” (IMF, 2020).

In September, it was decided that the escape clause would remain activated in 2021; and in early October the Spanish Cabinet asked Congress to activate the escape clause provided for in Organic Law 2/2012 on Budget Stability and Financial Sustainability, a decision that was first endorsed by Spain’s Independent Authority of Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF, 2020a). That request was approved on October 21st.

The collapse in tax revenue and growth in expenditure, analysed in detail by Sanz-Sanz and Romero-Jordán (2020), have driven a massive increase in the deficit, with the revenue shortfall responsible for approximately two-fifths of the increase and the remaining three-fifths explained by a surge in spending (Ministry of Finance, 2020b). As shown in Exhibit 1, the deficit, measured as a percentage of GDP and excluding local government, widened from 2.06% in the first eight months of 2019 to 7.07% in the same period of 2020. That five-point widening is primarily attributable to the central government, whose deficit increased by 4.2 percentage points. The Social Security deficit also widened considerably from 0.49% to 1.74%. Surprisingly, the regional governments’ public finances improved, from a deficit of 0.25% in 8M19 to a surplus of 0.19%, evidencing the central government’s strategic decision to protect them from the fiscal crisis. We will analyse that strategy in detail further on.

Outlook for 2020 and 2021

Exhibit 2 provides the Funcas consensus forecast for Spain’s public deficit in 2020 and 2021 (Funcas, 2020) and the forecasts set down by the Spanish government in its draft general state budget for 2021 (2021-GSB). For 2020, the consensus forecast is for a deficit of 12.4%, which is slightly more than one percentage point above the government’s estimate (11.3%). The difference between the two figures essentially boils down to the forecast contraction in GDP: the Funcas consensus estimate is for a contraction of 11.8%, whereas the government is forecasting a fall of 11.2%. AIReF (2020b) provides a range of deficit forecasts which run from 11.6% (at all levels of government) in the best-case scenario to 14.1% in the worst-case scenario.

On a comparative basis, Spain is on track to record one of the highest deficits in 2020. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2020), Spain’s deficit will rank fifth among the 35 developed economies analysed in its report. The reason is not the discretionary fiscal measures adopted, as Spain is among the least active on that front, placing just 19th among the 20 advanced economies analysed by the IMF. Instead, the origin of the higher deficit lies with the combination of an extremely high structural deficit, one of the highest output gaps among the OECD nations, and the fact that the Spanish deficit is particularly sensitive to GDP growth rates. The estimates made by Mourre et al. (2019) rank Spain among the EU nations with one of the highest elasticities of budget balance to output gap. Every point of contraction in GDP adds 0.6 percentage points to the deficit.

The high uncertainty regarding the remainder of 2020 is nothing compared to the forecasts for 2021 which are extraordinarily sensitive to the direction the pandemic takes and the effectiveness of the vaccines being developed. With those caveats in mind, the Spanish government and Funcas panel of analysts are calling for a significant rebound in GDP and a considerable improvement in the deficit, with the former estimating a deficit of 7.7% and the latter, 8.3%.

Regional government protection strategy

The budget surplus at the regional government level depicted in Exhibit 1 is worth highlighting as it had been over a decade – before the Great Recession – since the regional tier has recorded a surplus. And that is even though COVID-19 has necessitated extraordinary spending, particularly on the health front. The surplus in the first eight months of the year was running at 4.85 billion euros, which is equivalent to 0.44% of GDP (Ministry of Finance, 2020b). Moreover, the tax revenue transferred to the regional governments (inheritance & gift tax; stamp duty; gaming taxes; and car registration tax) has collapsed as a result of the economic slump and the fact that most of the governments have provided tax relief measures that are translating into the deferral of tax payments. According to the data compiled by the Ministry of Finance, their tax revenue was 25% lower year-on-year (equivalent to 0.2% of GDP) as of July.

Nevertheless, the central government has opted to protect the regional governments from the financial fallout from the health crisis, taking a different track to that of other federal states such as the US, where the fiscal crisis triggered by COVID-19 at the sub-central government level is very serious (Clemens and Veuger, 2020). The central government has instead opted for a combination of measures affecting the amounts transferred and advanced to the regional governments. By the end of August, 6 billion euros corresponding to the first tranche of the 16 billion-euro COVID-19 fund set up a few months earlier had already been transferred; 325 million euros had been deployed from the extraordinary fund set up to cover basic social service benefits; another 300 million euros had been transferred under the health and pharmacy benefits programme; and, execution of the State Housing Plan funding had been brought forward (447 million euros). Additionally, the definitive settlements paid under the regional financing system in respect of 2018 were higher than anticipated and the expected increase in advance payments corresponding to 2020 financing system settlement were already transferred between March and April (Ministry of Finance, 2020b). The latter decision is of particular importance as it lies at the heart of the regional governments’ income stream and means that the central government is transferring them funds as if the pandemic had not occurred, assuming the burden of the corresponding deficit and deferring the required adjustments until 2022, which is when the 2020 regional financing arrangements will be definitively settled.

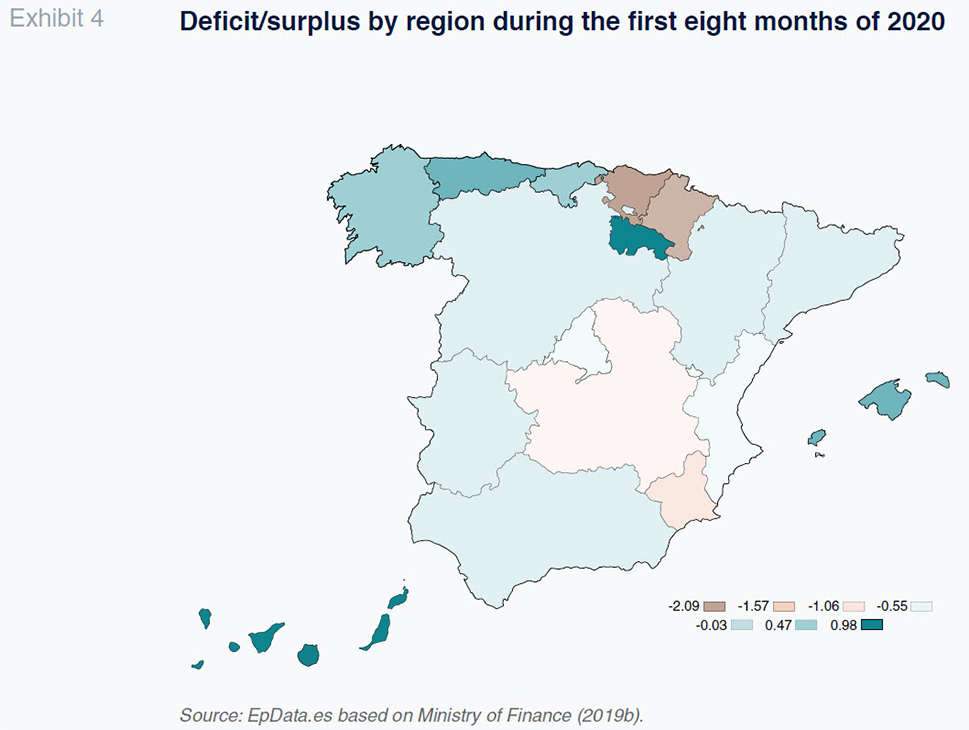

The consequences of these developments are illustrated in Exhibit 4. Most of the regional governments are presenting surpluses or very narrow deficits. Only the two regional governments with their own separate financing schemes (Basque region and Navarre), whose tax revenue is suffering the impact of the crisis, are reporting sizeable deficits of around 2% of their GDP. Despite the transfer of tranches 2, 3 and 4 of the COVID-19 fund, this situation is bound to deteriorate as the year unfolds as healthcare and other expenditure induced by the pandemic increase sharply. For that reason, AIReF (2020b) estimates an overall deficit at the regional government level of between 0.4% and 0.9% of GDP.

The strategy of protecting the regional governments’ finances is set to continue in 2021. Indeed, the financial support implied by the European recovery package means that the regional governments will see record spending ceilings. The 2021-GSB contemplates a slight reduction in income under the regional financing system from 116 billion euros in 2020 to 114 billion euros in 2021. Money from the extraordinary COVID-19 fund is also forecast to decrease from 16 billion euros in 2020 to 13.49 billion euros in 2021. However, the regional governments’ deficit ceiling will be lifted to 1.1% of Spanish GDP in 2021, which will easily offset the above-mentioned reductions in income.

[2] Most importantly, the regional governments will be handed direct management of 18.79 billion euros of the new European Community funds to support their economic recovery (Ministry of Finance, 2020a).

It is important to recall that the economic crisis is hitting Spain’s regional economies in differing degrees, varying above all as a function of their productive structures and the intensity of the health crisis. Taking note once again of the uncertainty clouding all economic forecasts, Exhibit 5 illustrates the diversity in the depth of the recession in 2020 and in the scale of the rebound anticipated in 2021. The exhibit, drawn up using estimates prepared by BBVA Research (2020), orders the regions by the net impact calculated for the two-year period. If we rebase 2019 to 100, in 2021 the Spanish economy would be back up at 93.7, with Castile-La Mancha at 95.5 and the Balearic Islands at 91.1.

The regional economies affected the most are the two archipelagos and, to a lesser degree, the two largest economies: Madrid and Catalonia. In general, there is no clear correlation between the impact of the crisis and GDP per capita prior to the pandemic, suggesting that the crisis will not accentuate regional inequalities observed in 2019. However, it will have a differential impact on the regional finances, despite the strong interregional levelling implicit in Spain’s approach. The deviation with respect to the average will be higher in the regions that are more reliant on fiscal autonomy, whether by virtue of having relatively higher GDP per capita or due the idiosyncratic nature of their financing systems (Canary Islands, Basque region and Navarre).

Unresolved issues and pending reformsThe pandemic has turned the regional reform agenda on its head. We started 2020 with broad consensus about the need to make strong progress on three fronts: reforming the regional financing system; getting the regional authorities back in the financial markets for debt placement purposes; and tightening fiscal governance to enhance budget stability at the regional level.

[3] However, the pandemic catapulted the need to guarantee the regions’ financial sufficiency in the short-term to the top of the agenda. That has been achieved by combining three instruments: transfer of regional financing system advance payments as if nothing had changed; extraordinary funds to cover the unforeseen expenses; and, liquidity guarantees. As a whole, the regional governments will head into 2021 with the idea that funding will not be an issue, that their fiscal stability duties are on hold and that the European funds will allow them to contemplate investments of an unprecedented scale.

Without a doubt, the extraordinary nature of current events justifies a shift in priorities and plans. However, it is important not to lost sight of the fact that the pandemic and the solutions being rolled out to address it will complicate an exit. The high level of advance payments made in 2020 and 2021 will generate record negative settlements in 2022 and 2023, which will jeopardise the regions’ financial sufficiency in those years. In all likelihood it will be necessary to adopt a solution similar to that used in 2008 and 2009 – spreading the negative settlement sums out evenly over a period of 10 years or longer. However, it is probable that such a strategy would not be sufficient to avoid sharp fiscal consolidation, particularly on the spending side. The depth of the recession in 2020 means that Spain will not revisit 2019 GDP levels until 2022 or 2023. And a recovery in GDP will take some regions longer than others. That will aggravate the sufficiency problem. This second major economic crisis of the century should open our eyes to the virtues of more responsible budget management, marked by budget surpluses and deleveraging during expansionary cycles, putting surplus regional financing transfers aside for years when growth is weaker.

The pandemic and its management have also shone the spotlight once again on the institutional deficiencies presented by Spain’s model of autonomous financing. The coordination and co-governance required of federal states warrants taking a fresh look at the structures in place.

Lastly, the management of even more regional debt in the hands of the state will increase the scale of this issue. Unquestionably, part of the solution to the challenges posed by the insufficiency of the financial facility funds (particularly the regional liquidity fund) is to reform the regional financing system in tandem with an overhaul of the Spanish tax system.

Notes

The author would like to thank Diego Martínez (UPO) for his valuable input and Fernanda Martínez and Alejandro Domínguez for their assistance.

Although the headline deficit target for the regional governments is 2.2%, that figure includes the 13.49 billion euros from the COVID-19 fund, which will be financed from debt taken on by the central government. The portion of the deficit to be financed by the regional governments is 1.1%.

On the first two matters, the report issued by the committee of experts (multiple authors, 2018) remains very much on point. On the third matter, and for some additional clarity on the second, we recommend reading the work of Martínez-Lopez (2020).

References

AIReF. (2020a).

Informe sobre la concurrencia de las circunstancias excepcionales a las que hace referencia el artículo 11.3 de la ley orgánica 2/2012, de 27 de abril, de estabilidad presupuestaria y sostenibilidad financiera [Report on the existence of the exceptional circumstances referred to in article 11.3 of Organic Law 2/202 on budget stability and financial sustainability]. Retrievable from

www.airef.es, October 13

th, 2020.

—. (2020b).

Monthly stability target monitoring. A. General Government. September 2020. Retrievable from

www.airef.es BBVA RESEARCH. (2020).

Regional Analysis Spain. Third quarter 2020. Retrievable from

www.bbvaresearch.com CLEMENS, J. and VEUGER, S. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Revenues of State and Local Governments: An Update.

AEI Economic Perspectives, 2020-07.

FUNCAS. (2020).

Spanish Economic Forecasts Panel. November 2020. Retrievable from

www.funcas.es IMF. (2020).

Fiscal Monitor. Policies for the Recovery. Retrievable from

www.imf.org LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2020). COVID-19: A Tsunami for Public Finances.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Volume 9 | number 3. Retrievable from

www.funcas.es MARTÍNEZ-LÓPEZ, D. (2020). La gobernanza fiscal de las Comunidades Autónomas. Una valoración crítica de su estado actual con perspectivas de reforma [Fiscal governance at the regional level. A critical assessment of the current situation with a view to reform].

Investigaciones Regionales / Journal of Regional Research, 47.

MINISTRY OF FINANCE. (2020a).

Presentación del Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales del Estado 2021 [Presentation of the Draft National Budget for 2021]. Retrievable from

www.hacienda.gob.es. October 28

th, 2020.

—. (2020b).

Ejecución presupuestaria de las Administraciones Públicas [Budget outturn figures] September 2020. Retrievable from

www.hacienda.gob.es. October 30

th, 2020.

MOURRE, G., POISSINIER, A. and LAUSEGGER, M. (2019). The Semi-Elasticities Underlying the Cyclically-Adjusted Budget Balance: An Update and Further Analysis.

Discussion Paper 098. Retrievable from

www.ec.europa.eu SANZ-SANZ, J. F. y ROMERO-JORDÁN, D. (2020): Impact of COVID-19 on Spain’s Deficit and Debt: Greater than Initially Expected.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Volume 9 | number 4. Retrievable from

www.funcas.es SEVERAL AUTHORS (2018). I

nforme de la comisión de expertos para la revisión del modelo de financiación autonómica [Expert Committee report on reforming the regional financing regime], Madrid: IEF.

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics (University of Vigo)