Spain’s fiscal consolidation: 2016 performance and outlook for 2017

A relaxation of original deficit targets should help the government stay on track to meet fiscal consolidation goals in 2016. However, meeting targets in 2017 will be a more ambitious task, which will be difficult to achieve in the absence of additional adjustment measures.

Abstract: Even in the face of greater political stability, a more favourable economic backdrop, and substantial upward revisions to original deficit targets, fiscal consolidation has been far from an easy task to achieve in 2016. Nevertheless, there is a high probability that Spain will meet its 2016 deficit targets. Consolidation in 2017 appears to be more challenging, given that, at present, neither the social security system, nor the regions are expected to be able to bring down their deficits substantially, while the surplus at the local corporation level is not expected to increase and may even be reduced. Deviation from these subsectors means that the central government will likely have to bear the brunt of fiscal adjustment. Under current conditions, consensus expects slippage in 2017. However, reaching agreed upon fiscal objectives may still be feasible, but unlikely without additional measures, particularly in the area of tax revenues.

The process of preparing and debating the General State Budget for 2016 (PGE-2016) was brought forward by a quarter to allow it to be approved before general elections, which were finally called in December 2015. The approach posed risks but it also had advantages (Lago-Peñas, 2015). Faced with the likely loss of absolute majority, there was a high probability that the PGE-2016 would be changed at the start of the year to adapt it to a different government and/or Parliamentary configuration. Furthermore, the government faced criticism from the opposition that it was assuming responsibility for something (planning the budget for the upcoming year) that was not necessarily to be under its mandate, given the upcoming elections. On the other hand, bringing forward the budget ensured certainty and continuity in the management of public finances and the consolidation process. Hindsight suggests the government’s decision may have been the right one. Repeated elections and the difficulties in forming a government, let alone approving a new PGE, increased the value of having a budget already in place for 2016. Without it, we would still be with the extended PGE-2015 today.

Even so, during a large part of 2016, the interim government and difficulties in reaching political consensus have meant that budgetary execution and planning have been overseen by a sort of “autopilot”, which has only been disengaged sporadically to respond to alarms, mainly originating from external sources (i.e. the European Commission). It is also true that the economic backdrop has been favourable. Real GDP grew by 3.2% in 2016, clearly above what was anticipated when the Budget was being prepared. But it is equally true that the fiscal consolidation process is far from over, with significant challenges stacking up on various fronts. In particular, the reduction of the cyclical deficit remains clearly insufficient.

The aim of the article is to analyse recent developments and short-term perspectives for the Spanish public sector as a whole and for each of the four sub-sectors of the public administration (local, regional, central government and social security). Specifically, the article reviews budgetary execution using latest available data to November 2016, as well as identifying the risks to fiscal consolidation and lines of action in 2017 in each of the four sub-sectors.

The General government

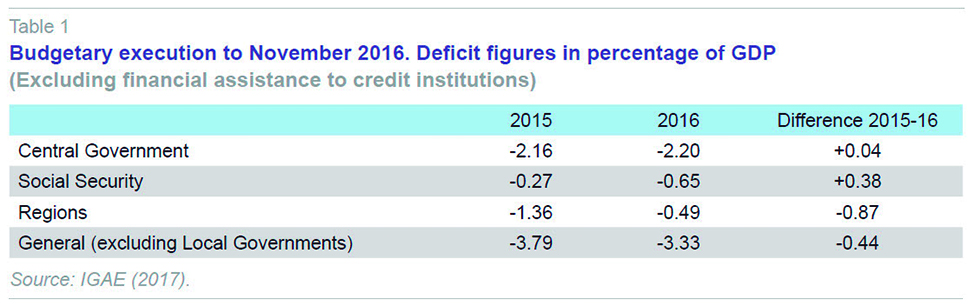

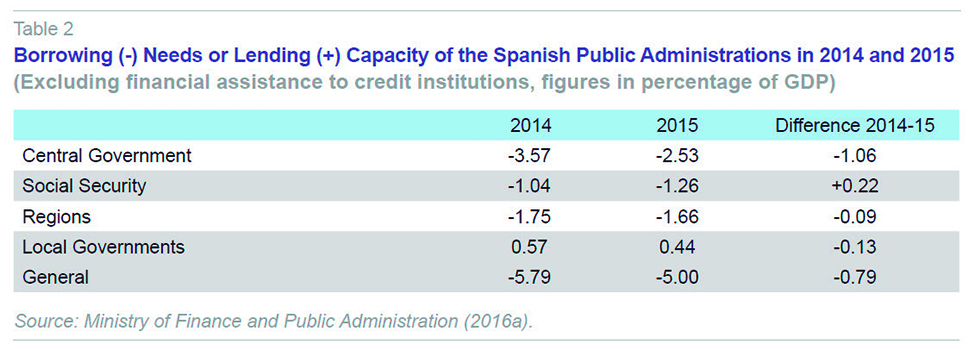

Table 1 presents budgetary execution by the central government, social security system and autonomous regions to November 30th, 2016. The values refer to borrowing (-) needs or lending (+) capacity as a percentage of GDP, according to National Accounting methodology. They are accompanied by data for 2015 to provide context to the analysis. Table 2 summarises the deficit (-) or surpluses (+) of the four sub-sectors and for General government as a percentage of GDP. Both tables exclude financial support measures.

The data depict a progressive reduction in the deficit, albeit at a slow pace. Barely 0.8 percentage points (ppts) of adjustment occurred in 2015 and less than 0.5 ppts in 2016 according to November data. Despite registering real GDP growth of over 3% in 2015 and 2016, and a concurrent reduction in the output gap, the Spanish economy is showing certain shortcomings in its ability to reduce the structural disparity between public revenues and expenditures. The latest forecasts underline this assessment. Funcas Consensus for January 2017 points to a deficit of -4.5% of GDP; the Bank of Spain is slightly more upbeat, at -4.4%; meanwhile the European Commission increased their estimate to -4.7% in the winter 2017 forecasts. Meanwhile, the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF) projected in July that the deficit for the year would be over -4% (AIReF, 2016a).

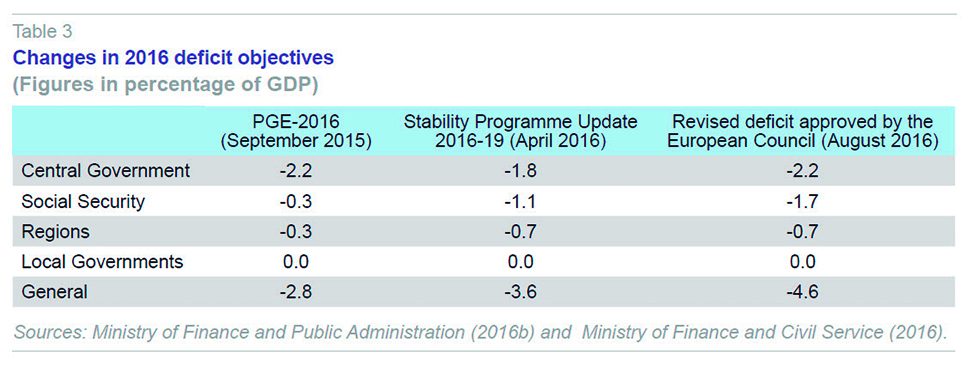

At the same time, it is important to keep in mind the substantial upwards revisions to the deficit targets that have taken place since approval of the PGE-2016 in September 2015 (Table 3). These have led to the target being revised up from the original -2.8% to -3.6% presented in the Stability Programme update 2016-19 in April and to the eventual -4.6% approved by the European Council in August, which now applies to the government. As such, the target has been moving and adapting to the reality revealed by budgetary execution data. The current target looks likely to be achieved. AIReF (2016b) puts the probability of compliance at two-thirds, thanks to the impact of measures relating to payments on account in corporate tax and the spending freeze. However, repeated upward revisions of targets push Spain further away from the -3% threshold, which it should have already met in 2016, and raise concerns about the country’s capacity to reduce the deficit in the absence of more ambitious reforms, particularly in the tax realm.

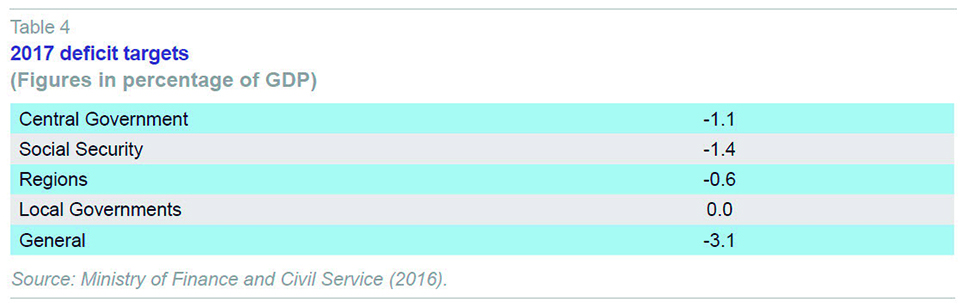

The target has also been softened for 2017 (Table 4), but nonetheless implies reducing the deficit by 1.5 percentage points in the context of weaker real economy growth (around 2.5%), albeit with a rising deflator.The final outturn for 2016 will be key to determining the likelihood of reaching the -3.1% target for 2017. The Draft Budgetary Plan for 2017 sent by the Spanish government in December 2016 (Finance Ministry, 2016) sets out the scenario. In the absence of PGE-2017, the previous year’s Budget will be rolled over, maintaining the spending ceiling at the level forecast for 2016 (below the initial budget), through a non-availability agreement amounting to 5 billion euros, and the approval of a package of tax measures with an estimated impact of 7.5 billion euros.

[1] On top of this, 900 million euros of savings are expected to come from the public administration reform programme (the so-called CORA programme). In total, 13.4 billion euros of adjustment, which equate to 1.2% of GDP, are forecasted for 2017. All of these measures would have to be applied by the central government, which would therefore take on the lion’s share of the deficit adjustment. Subsequent sections of this article set out some of the discretionary measures envisaged for the other sub-sectors.

Will it be enough? According to the European Commission’s winter forecasts published in February, the answer is no. Spain’s deficit will only fall to -3.5% of GDP this year – for various reasons. Firstly, real GDP growth will be weaker than forecast by the Spanish government (2.3% compared to 2.5%). Secondly, the deficit will end 2016 at 0.1 percentage points above target (-4.7% instead of -4.6%). Thirdly, the revenue and expenditure forecasts for the different discretionary measures that have been announced are optimistic. Funcas Consensus for January 2017 believes that the 2016 deficit should be met (-4.5%), but that the government will overshoot the 2017 target (-3.4%,

[2] in line with the European Commission).

The end of March will shed some light on some of these uncertainties. Firstly, we will find out about budgetary execution and the final deficit for 2016. Secondly, we will have new macroeconomic forecasts from a range of public and private institutions; although the signs are that optimism regarding the economy’s performance will continue to prevail and consensus will be around 2.5%, i.e. close to the government’s growth forecast. The government also intends to present the PGE-2017 at the end of March with the aim of securing sign-off in June. This will create a new scenario for the development of deficit targets. The government is set to once again take a grip of the budget and the fiscal consolidation process, switching off the “autopilot” over the last year and a half. This will provide a clear opportunity to review the coherence of the current accounts, but it is also true that relative inactivity in recent quarters will condition the extent of spending execution. Reactivating execution will require sufficiently ambitious compensating adjustments.

The central government

The central government significantly reined in its deficit between 2014 and 2015 but the reduction appears to have attenuated in 2016. Execution data to November point to stagnation with a marginal increase of 0.04 ppts relative to 2015. This is not an expenditure story; spending remains under control. In fact, spending fell by 0.8% to November compared with 2015, thanks in a large degree to the reduction in interest outlays and subsidies to companies (specifically, related to covering the energy deficit), the non-availability of credit agreements and the early shut-down of PGE-2016 accounts in July (Ministry of Finance, 2016c). The deterioration is instead due to the poor performance of tax revenues. Specifically, current revenues from income, wealth and capital taxes (General State Comptroller, IGAE), which suggest there has been a larger impact from the direct tax cuts than originally anticipated by the government (AIReF, 2016b). This, despite the very positive impact in October from changes to payments on account in corporation tax, which were approved by the central government in September under Royal Decree 2/2016.

Following the revision to the global target in August 2016, the central government’s target went back to the objective set out in the PGE-2016: -2.2% of Spanish GDP (Table 3). However, the deficit was already above this target by November 30th. It should also be remembered that budgetary execution typically deteriorates between November and December. In 2015, the deficit jumped from -2.16% to -2.53% and in 2016 from -3.15% to -3.57%. Nonetheless, AIReF (2016b) believes the target could still be achievable, although their central estimate (the most likely) is for an outturn of 2.3%, a deviation of 0.1 percentage points.

Social security system

The social security system has been a clearly source of fiscal slippage in the public accounts in 2016, as it was in 2014 and 2015. Revenues are not recovering in line with growth in employment, this is due to: the effect of hiring subsidies; the reduction in wages in recent years, which particularly affects new workers and those who have changed jobs; reduced transfers from the central government to finance the State Employment Service (SEPE); and even the reduction in interest income accruing to the reserve fund itself. According to AIReF (2016b), the social security deficit could come in at close to 1.6% of GDP, with a very high probability of complying with the revised target. But it is important to keep in mind the information set out in Table 3. The initial target has been revised up from -0.3% to -1.7%. This increase of 1.4 percentage points accounts for nearly 80% of the additional margin granted to the public finances overall. The social security system is currently the biggest fiscal consolidation hurdle facing Spain.

In his recent appearance before the Pacto de Toledo committee in Parliament on February 9th, 2017, AIReF’s President stated that it was unlikely that the social security system would meet its 2017 target (-1.4%) in the absence of additional measures. He explained that AIReF’s central best estimate for this year was currently very similar that at the close of 2016, at around -1.7%.

Autonomous Regions

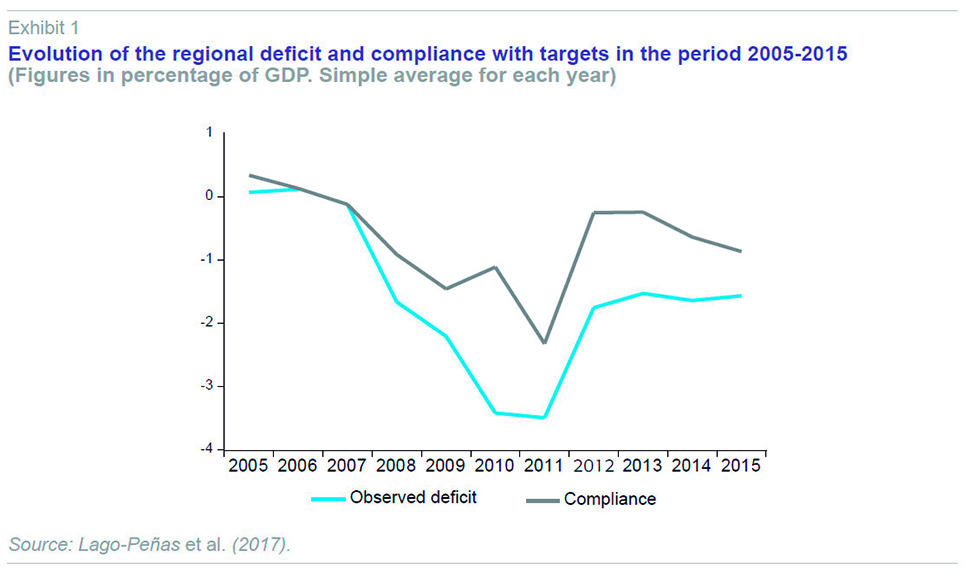

Since the outbreak of the economic crisis in 2008 the regions have consistently failed to comply with their deficit targets. Exhibit 1 from Lago-Peñas et al. (2017) shows both the registered deficit and the degree of compliance with targets, defined as the difference between the target and outturn. Thus, compliance with the target implies a 0 variable and the degree of non-compliance increases as the value becomes more negative. In both cases, the averages are not weighted. Following improvements in 2012 and 2013, regional consolidation deteriorated in 2014 and 2015. This is more due to the reduction in the targets than an increase in the deficit itself. In fact, it had appeared as though the regions overall had run into a floor in terms of bringing down their deficit, at around -1.5% of GDP.

Regardless, it is important to emphasise that throughout the period, there has been a wide disparity in performance by regions around the average, which is explained by various factors. It particularly reflects the differences in resources received from the regional financing system by each autonomous region and differing degrees of effort in pursuit of consolidation targets. Some regions have been broadly compliant: Andalusia, Castile-Leon, Asturias, La Rioja, Aragon and – especially – the Canary Islands, Galicia and Madrid. Meanwhile, Mediterranean-facing regions have dominated the other end of the spectrum: Murcia, the Valencian Community, Catalonia and the Balearic Islands have systematically breached their targets (Lago-Peñas et al., 2007).

While faced with a similar target to 2015 (-0.7%), 2016 has seen a substantial and widespread reduction in the regional deficit. According to AIReF, on the basis of data to the third quarter, the deficit for the regions as a whole stood at -0.9% of GDP. This outturn has less to do with discretionary adjustment measures taken by the regions (spending cuts and tax increases), but rather the increased revenues provided by the regional financing system (common regime).

[3] Even so, performance will once again be patchy across regions. It is highly likely that Extremadura, Murcia, Cantabria, the Valencian Community, Aragon, Catalonia, Castile La Mancha and Castile-Leon will overshoot the 0.7% deficit target. Overall, the aggregate regional deficit could come in around 0.2 percentage points above target, but this will put the deficit back at pre-crisis levels. FEDEA (2016) is somewhat more optimistic, judging that the 0.7% objective could be achievable based on extrapolating data for the first half of the year.

In terms of 2017, AIReF has published its report on the probability of non-compliance, believing the -0.6% of GDP stability objective for the sector as a whole could be achievable. However, AIReF’s central estimate is for a deficit of -0.7%, highlighting the difficulties in continuing to reduce the deficit. The problem centres on eight regions who are judged to be very unlikely (Aragon, Cantabria, Extremadura and Murcia) or unlikely to be compliant (Catalonia, Castile La-Mancha, Navarre, Valencian Community) (AIReF, 2017).

Local governments

Once more the local governments will end the year with a surplus, helping to compensate deficit deviations in other administrations in 2016. Good fiscal compliance by the local tier is strongly related to central government restrictions on spending on non-mandatory competences, the application of the spending rule and increases in Property Tax rates (IBI) imposed by the central government. Data on execution for the first three quarters of the year point to a substantial increase in the surplus compared to the same period last year, reaching +0.52% of GDP (+0.33% in 2015). This is mainly due to the liquidation of the financing system, which has produced a favourable outcome for local entities in 2016 of around 923 million euros, compared to a negative outturn of 772 million euros in favour of the central government in 2015 (IGAE, 2016).

BBVA Research (2017) estimates that the local governments ended 2016 with a surplus of +0.5%. AIReF (2016b) analysis prepared before receiving third quarter data is somewhat less optimistic, forecasting a surplus for the year of 0.4% of GDP, slightly below 0.5% in 2015. AIReF (2016c) expects the 2017 target (0.0%) will be amply met, although the surplus looks to be on a downward path and their central estimate is for a surplus of around +0.3% due to the decision not to extend revenue measures (increase in IBI rates) and increased flexibility introduced on the spending rule.

Conclusion

There is a high probability that Spain will meet its 2016 deficit targets. This is mainly because the objectives have moved in line with data on budgetary execution. The surplus at the local level will compensate overshooting by the regions and the central government, with the social security system likely to come in at close to target (1.7%). 2017 looks set to be a more ambitious undertaking. The overall target is 1.5 percentage points lower than that in 2016, with the central government set to bear the brunt of the adjustment. Neither the social security system nor the regions will significantly bring down their deficit in the absence of additional measures. The surplus at the local level will likely not increase, in fact it is more likely to move in the opposite direction. Overall, these three sub-sectors could close the year at around 2% ‒ similar to 2016 and requiring the central government to halve its 2016 deficit. The task is a feasible one against a favourable economic climate, but will require additional measures either on the central government accounts, in the social security system or to address less compliant regions.

Notes

The breakdown is as follows: 4.7 billion euros as a result of the elimination of subsidies and deductions on Corporation Tax; 150 million euros relating to the increase in excise duty rates on tobacco and alcohol; 200 million euros from a new tax on sugary drinks pending approval; 500 million euros from the first phase of the “green tax reform” which will launch in 2017 with a focus on greenhouse gases; 1.5 billion euros relating to changes in tax administration (specifically, the elimination of the possibility to grant deferments on VAT charged, instalment payments or frozen debts while an appeal is being processed); finally, 500 million euros from the fight against fraud, thanks to the new instantaneous VAT information system and the new limit on payments in cash, which will fall to 1,000 euros per transaction.

Funcas Consensus forecasts for March provide deficit projections for 2017 and 2018. The latest forecast for 2017 is now -3.4%.

Particularly the ex-post liquidation of the 2014 financial year, which is paid in 2016. This liquidation is worth 7.6 billion euros (Ministry of Finance and Civil Service, 2017), equivalent to nearly 0.7% of Spanish GDP and accounts for around 90% of the reduction in the deficit in the 2016 forecast by AIReF.

References

AIREF (2016a), Report on compliance with the Budget Stability and debt targets and with the expenditure rule 2016 by the different public administrations, 19-7-2016.

— (2016b), Surveillance of budgetary execution. Third quarter of 2016, 5-12-2016.

— (2016c), Report on the Projects and Main Budgetary Lines of Public Administrations: Local Corporations 2017, 5-12-2016.

— (2017), Report on the main aspects of Public Administrations’ budgets and initial budgets for 2017: Autonomous Regions, 14-12-2017.

BBVA RESEARCH (2017), Spain Fiscal Observatory, 23-2-2016.

FEDEA (2016), Ninth Report of the Fiscal and Financial Observatory of the Autonomous Regions, 31-10-2016.

IGAE (2016), Quarterly report. Consolidated national accounts data. October 2016, 27-12-2016.

— (2017), Monthly report. Consolidated national accounts data. November 2016, 31-1-2017.

LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2015), “The 2016 General State Budget: Balancing Fiscal Consolidation and the Electoral Cycle,” Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 4(5).

LAGO-PEÑAS, S.; FERNÁNDEZ-LEICEAGA, X., and A.VAQUERO (2017), “Why are the Autonomous Regions fiscally non-compliant?,” Investigaciones Regionales – Journal of Regional Research, forthcoming.

MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (2016), Updated of Draft Budgetary Plan 2017. Kingdom of Spain, 9-12-2016.

— (2017), Fiscal policy strategy, 2-2-2017.

MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION (2016 a), Deficit of the Public Administrations 2015, 7-4-2016.

— (2016 b), Kingdom of Spain Updated Stability Programme 2016-19, 29-4-2016.

— (2016 c), Draft Budgetary Plan 2017, Report of effective action, 14-10-2016

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics research Network (GEN). University of Vigo