Analysing payment trends in Spain

Although recent data point to a change in trend among Spanish payment cardholders towards an increased reliance on PoS card payments versus ATM cash withdrawals, Spaniards still use cash more often than card-based payments. Whether this dynamic reflects current obstacles in the evolution of the card-based payment market, or simply Spaniards’ payment habits, Spain currently lags behind its EU peers as regards use of cards relative to cash payments.

Abstract: Spaniards’ payment habits are shifting in the expected direction but not at the expected speed. The fact that Spaniards still use cash more often than card-based payments, that one in four still only uses cash and that just 7% pay for their purchases only with cards, suggests that there is still a long way to go in terms of encouraging card usage- particularly among small retailers and, generally speaking, for micro payments. There have been some noteworthy structural changes in both domestic and international payment card schemes. However, mass adoption of card-based payments (whether physical or virtual) or A2A electronic payments, as soon as this segment develops acquiring solutions, currently faces obstacles that need to be pinned down from the standpoint of all involved. It remains to be seen whether or not Spain’s relative failure to wholeheartedly embrace e-payments is the result of preferences or rather existing impediments in the electronic payments market.

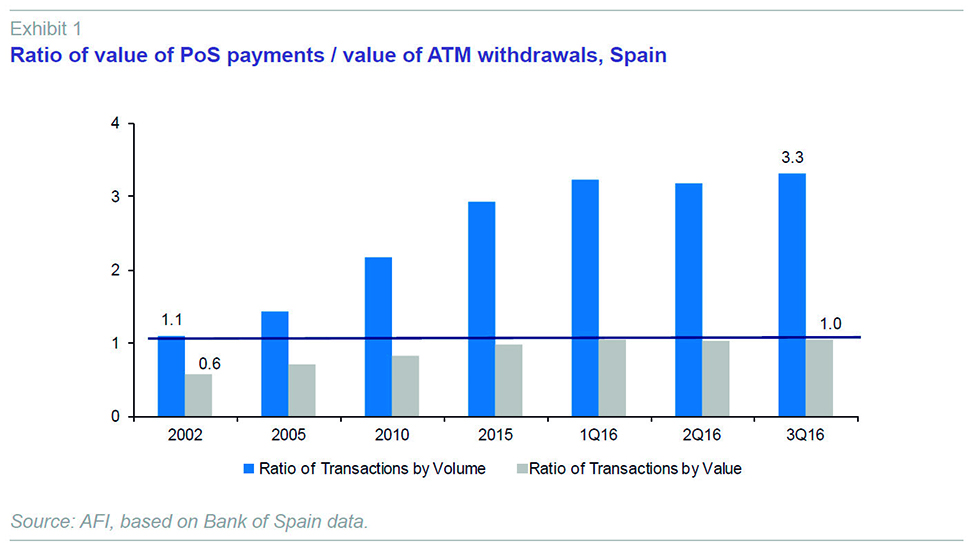

In the first quarter of 2016 ‒ exactly one year ago ‒ Spain registered a shift in trend in relation to user habits by payment cardholders. For the first time, the value of PoS card payments exceeded the value of ATM cash withdrawals. Accordingly, the ratio of the ‘value of PoS payments/value of ATM cash withdrawals’ exceeded one for the first time.

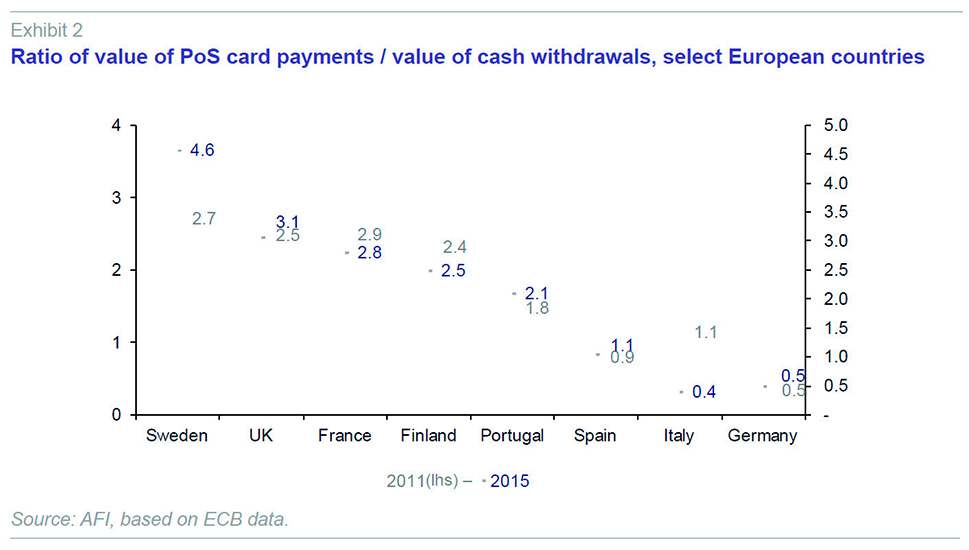

This progress on the use of cards is eclipsed if we analyse the ratio with a little more context, at least at the European level. Spain is not only the laggard among the countries selected as benchmarks, but also displays extreme sluggishness in changing habits in light of its starting position as group straggler. Only Italy (intensely) and France (less so) present a contraction in the ratio in question since 2011. Germany is at the bottom of the selected universe of countries, withdrawing twice as much cash from ATMs relative to card-based PoS payments. Sweden and the UK are making strong progress, while Finland, Portugal and Spain are making slower progress, albeit coming from different starting points.

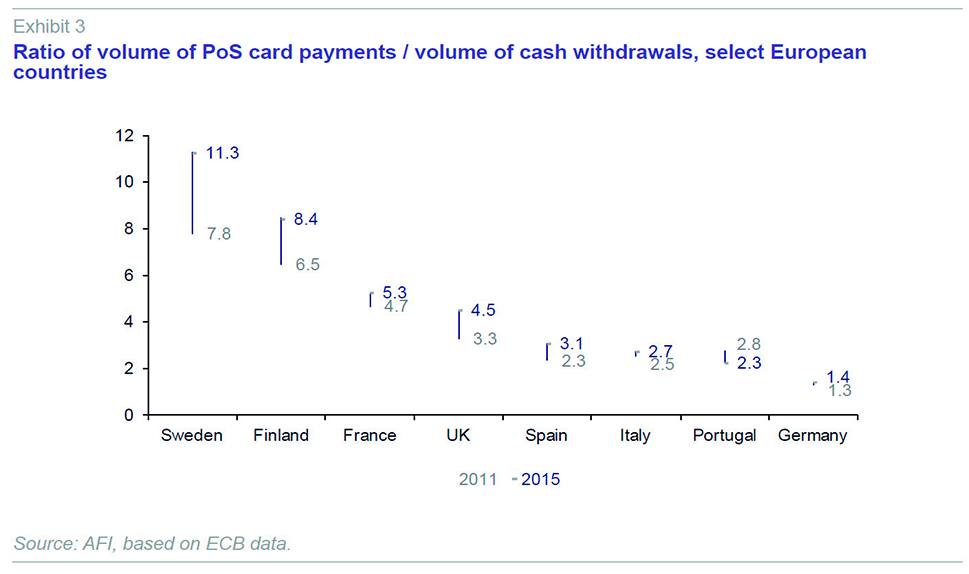

By transaction volumes, Sweden (where card payments are 11 times more frequent than cash withdrawals) and Finland (over 8x) are way ahead of Spain (over 3x). Some countries, such as Denmark, according to data published by the ECB, do not present cash ATM withdrawals using domestic bank-issued cards: all card transactions take place at the point of sale.

Cash remains a constant and permanent presence in our everyday payments

Public statistics about the use of cards do not reveal the motives driving their usage, which is why it is necessary to obtain demand-side (user) information in order to be better armed when attempting to identify user motives or impediments.

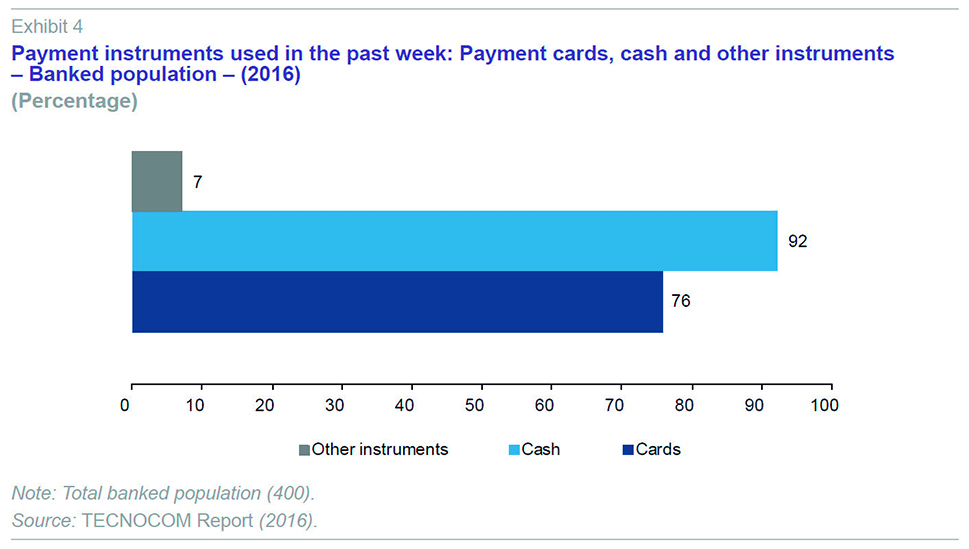

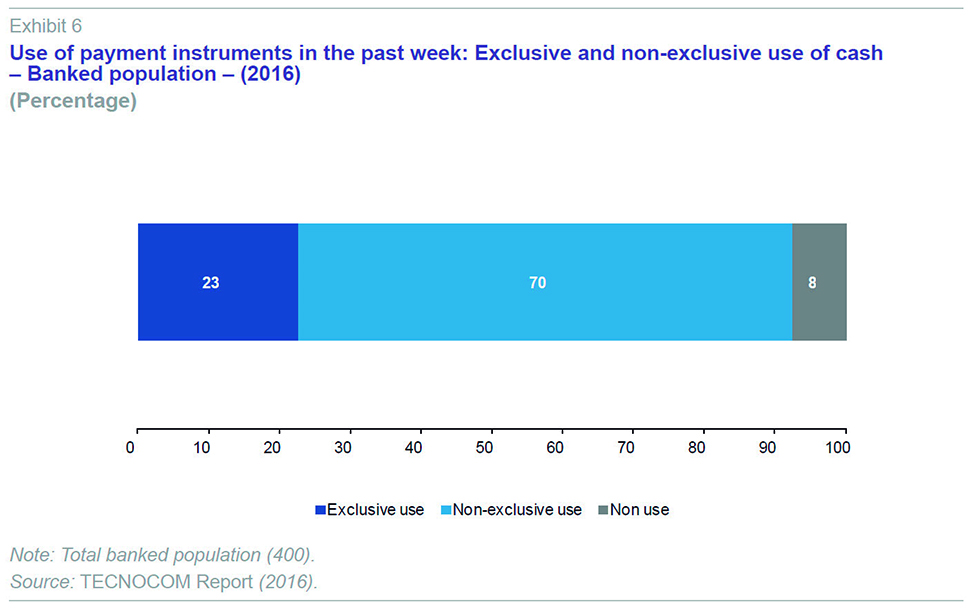

The demand-side study conducted against the backdrop of the TECNOCOM Report on Trend in Payment Instruments, 2016, a report in whose preparation Analistas Financieros Internacionales (A.F.I.) actively participates (see Tecnocom, 2016), researches, among other matters of interest, everyday purchase payment habits in Spain and six Latin American countries. When analysing the specific instruments used to pay for weekly expenses in Spain, it is very illuminating to note that cash payments continue to outstrip card payments: 92% of ‘banked’ individuals use cash daily, 16 points more than those who say they use cards daily.

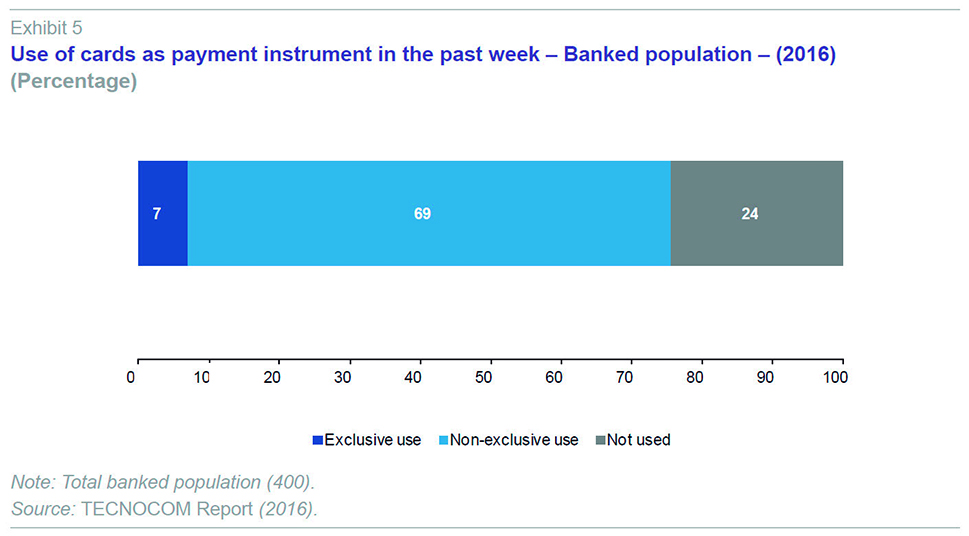

Another insightful finding relates to the use of cards to pay for weekly expenses: exclusive use of cards is not very entrenched in Spain, with just 7% of the banked population (holders of a payment card or bank account) using only their cards to pay for everyday items.

This finding complements the fact that 23% of the banked population in Spain claims to use only cash to pay for their frequent purchases.

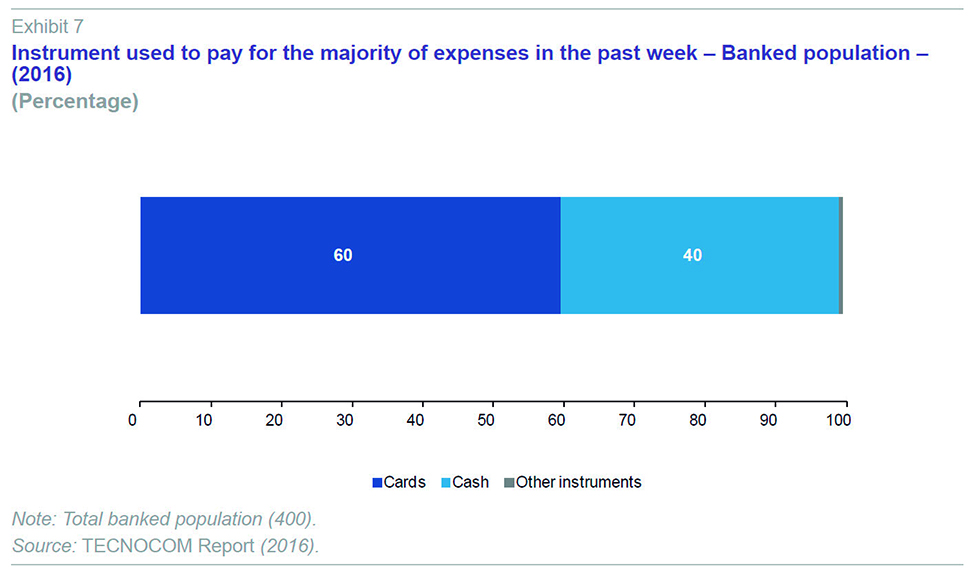

When asked about the instruments used to pay for the majority of expenses in the past week, the relationship between cash and cards changes substantially. Cards outweigh cash in Spain when it comes to the instrument used to pay for the majority of expenses (60%). Accordingly, it is in the sphere of micro payments (payments of small amounts) that the use of cash is more widespread.

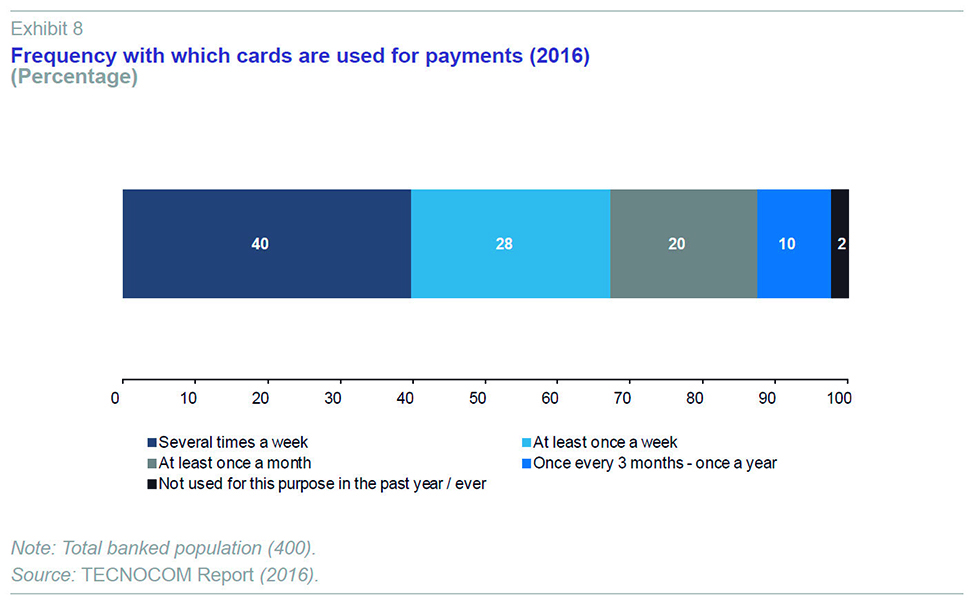

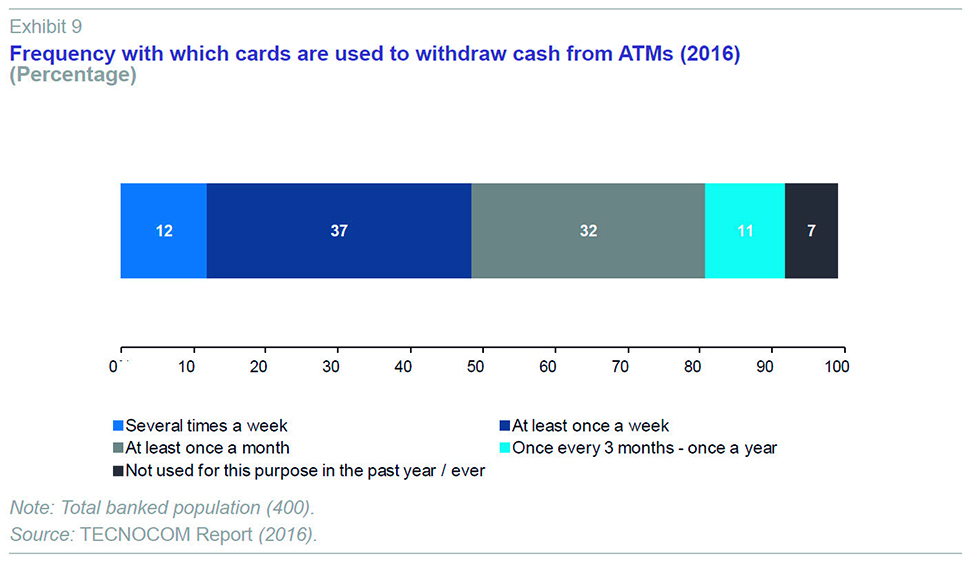

The use of cards to withdraw cash (essentially via an ATM) is markedly different than the pattern observed for usage as a means of payment. The 2016 Tecnocom Report reveals that 49% of banked Spaniards visit an ATM machine to withdraw cash once or more a week. Thirty-two per cent say they make ATM cash withdrawals every month. Seven per cent ‒ presumably the same people who only use cards for frequent payments ‒ claim not to have visited an ATM in the past year.

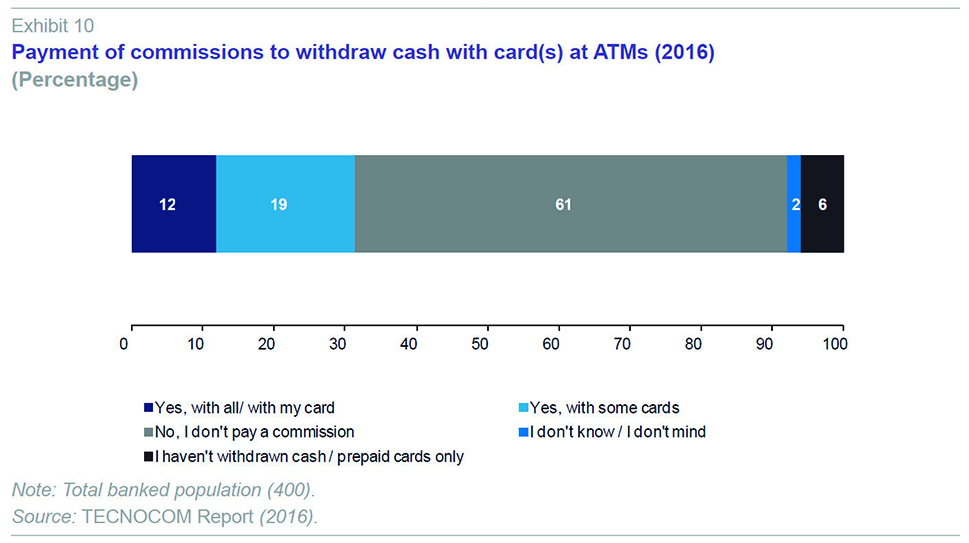

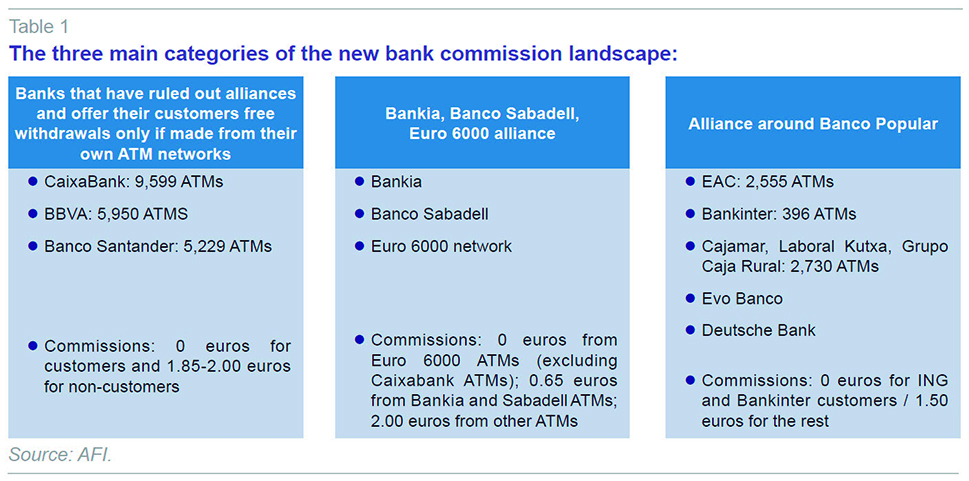

The cash withdrawal landscape (ATM network) has been significantly fragmented by the decision taken by the banks with the largest network of ATMs, subsequently seconded by other ATM network owners, to discontinue the agreements among the three networks operating in Spain (Servired, 4B and Euro 6000) covering the free use of ATMs by customers across the various networks. Although 61% of cardholders said in 2016 that they do not pay a commission to withdraw cash, 31% said they do (when using some or all of their cards), most commonly for the withdrawal of cash from ATMs that do not belong to the financial institution that issued their cards.

Under the former collaboration in place until 2016, the bank that owned the ATM charged the card-issuing bank a previously agreed-upon fee, on a multilateral basis, within the network system in question (i.e., 4B, Servired or Euro 6000). The latter then charged its customers a commission for this service or assumed the cost without passing it on to their customers. Under the new regime, membership of the same network no longer guarantees equal terms of ATM usage for holders of bank cards issued by members of those networks. The commission policy for withdrawing cash from ATMs owned by entities other than the card-issuing bank, regulated by the Bank of Spain since 2016 (see, Bank of Spain), has virtually fully dismantled the advantages that were to be had from using ATMs belonging to a given network system. The members of the Euro 6000 system are the only ones to have kept their alliance intact.

It would be interesting to find out whether the act of getting money from the cash machine could be replaced, by means of a simple change of habit, by direct PoS card payments. Because, if this were possible, card holders would stand to save a lot of money in cash withdrawal commissions (looking only from the customer perspective).

Habits are an aspect of our behaviour that are very hard to change. Identifying the main motives underpinning our conduct ‒ in this case an attachment to cash and the comfort it provides us – is a complex but potentially illuminating task.

Insofar as the paying agent (card holder) does not incur any cost to use a card (without considering the card issuance fee, payment for the service associated with holding the card or the possible borrowing cost if used for credit), the next step is to analyse the cost borne by the collecting agent (user of PoS terminals to accept card payments, i.e., the merchants).

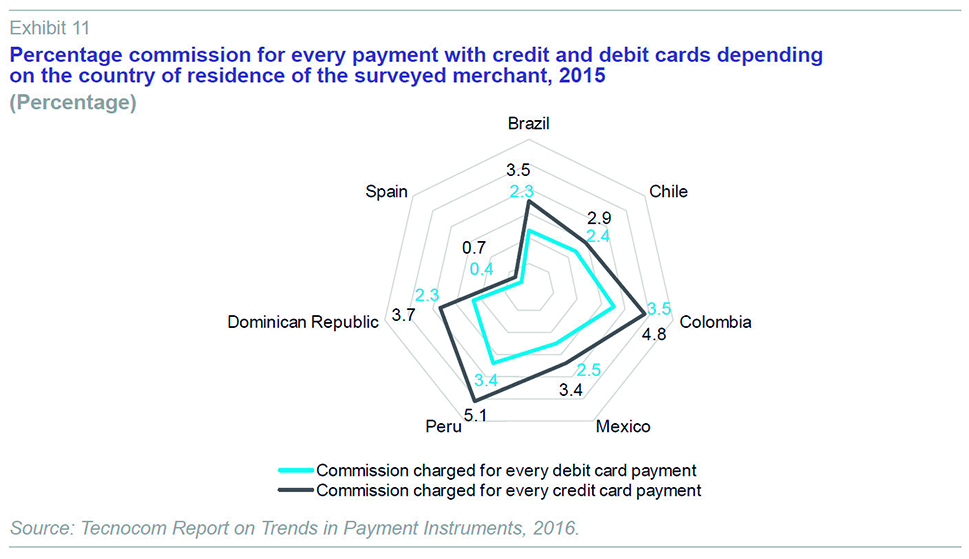

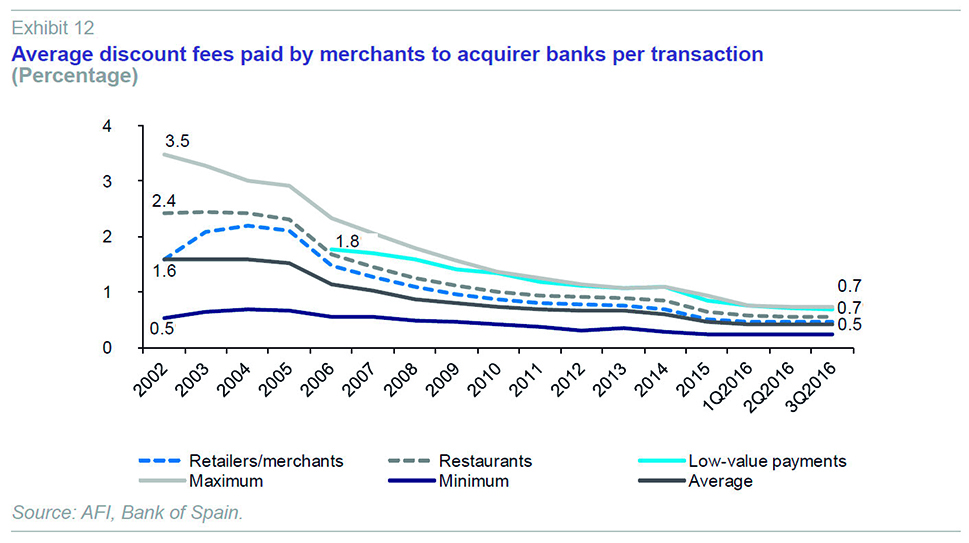

The 2016 edition of the TECNOCOM Report focused its demand survey on the small retailer or merchant angle. Asked about the commissions (merchant discount fees or merchant service charges) they had to pay their acquirer banks for every payment settled with a credit or debit card, small merchants in Spain with PoS devices said that the fee ranged on average between 0.4% (for debit card payments) and 0.7% (credit card payments).

Turning to the data published by the Bank of Spain, what stands out is, firstly, how accurately the merchants calculated their fees ‒ the minimum and maximum fees reported by the PoS device network operators and the merchants themselves fully coincide ‒ and secondly, the trend in those fees in the small merchant segment in Spain. These fees have historically remained below the average rate, in contrast to the “low-value payments” category, which since 2010 are charged at the average maximum commission. According to the Bank of Spain, the “low-value payments category” includes “categories of retail payments (other than toll roads) for which card payments on average do not exceed 15 euros and whose prices are, in general, conditioned by a particular regulatory framework, such as urban transportation, metro, commuter trains, car parks and phone cabins, among others”. In short, what are currently termed micro-payments.

The power of negotiation wielded by payment volumes and values is an element that is evident in the discount fee scale published by the Bank of Spain: large merchants pay discount fees that are on average around 50% lower than those borne by their smaller peers (in the past they paid as little as 30% of what small merchants paid). As for the “low-value payments” category, it is worth noting very recent initiatives such as those involving the public transport systems in some Spanish cities. Madrid’s public transport manager, the EMT, which carries around 1.5 million passengers every day, has announced plans to upgrade all the ticket validation machines in its bus fleet to configure them for card payments starting this May, having successfully test piloted the initiative in two lines in March 2016 (#27 and the express airport line). Madrid’s Metro, meanwhile, eliminated its minimum payment

[1] (which was 5 euros) for the purchase of one-way tickets, multiple tickets or monthly top-ups at disbursing machines, as well as broadening the range of cards taken (adding JCB and American Express) in November 2016.

International and domestic payment card schemes

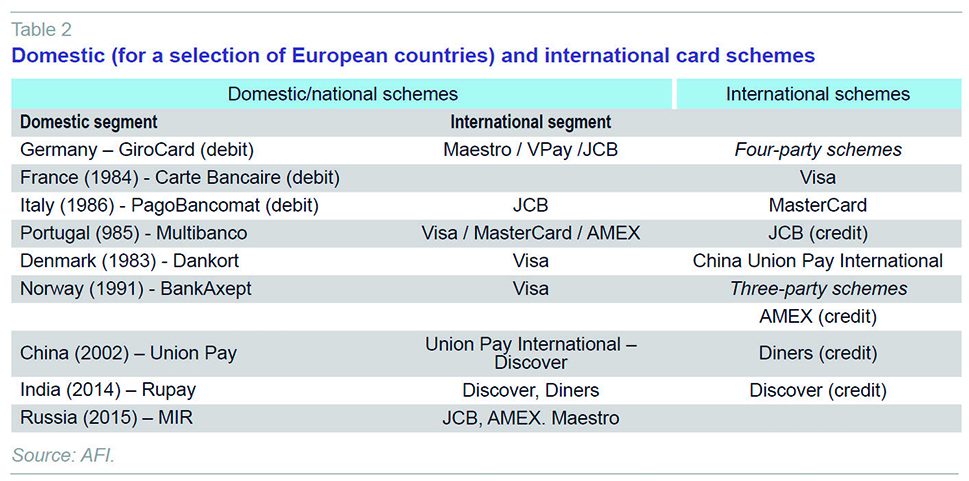

Card schemes are payment networks associated with payment cards (debit, credit and prepaid cards) of which a bank or financial institution may form part under a brand licensing agreement, accrediting its ability to issue or acquire cards that operate in that scheme’s network.

In card payments there is no company comparable in size or reach to the global leaders, all of which are North American, with the exception of China Union Pay International.

[2] Other networks such as Japan’s JCB and Discover are gradually expanding their issuer network internationally via agreements with domestic payment networks. Maestro is a multinational debit card service owned by Mastercard and created in 1992; VPay is a European Visa card owned by Visa Europe since 2004.

Europe used to be a fragmented market with multiple card schemes that rarely crossed borders in which nearly all countries (Western) had their own national card schemes with their own rules and standards, which only worked locally.

[3] The Payment Services Directive and SEPA Cards Framework (SCF) radically changed this landscape: on the one hand, the domestic card schemes in the UK

[4], Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Finland were replaced by the leading international card brands, VISA and MasterCard (in their various credit and debit formats). On the other hand, in countries such as Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France and Germany, the domestic schemes continued to dominate over the international schemes, with which they compete in the domestic sphere.

[5]

Strong domestic schemes allow banks and payment service providers (PSP) to generate know-how with respect to local idiosyncrasies and user behaviour and preferences, which translates into a refined ability to innovate when developing new products, services and solutions that are more likely to succeed in the local market.

[6]

As for transaction costs, Veitch and Bott (2014) found evidence that the costs of the domestic schemes are equivalent, on average, to 45% of those associated with using international card brands (the big players, Visa and MasterCard) for domestic payments.

[7] To the extent that over 90% of all transactions are domestic (92% in Spain, representing 87% by value, according to the ECB), this cost difference is by no means insignificant for issuer and acquirer banks.

[8] Historically, the domestic schemes (in Spain: Servired, 4B and Euro 6000) have agreed with their international counterparts that the domestic agent would handle local transactions and the international agent would handle international transactions under ‘co-badging’ arrangements with the international brands. This model, however, is beginning to be rendered meaningless due to the growth in competition, coupled with the fact that in Europe the withdrawal of Visa Europe

[9] is likely to derive in an increase in the fees charged by Visa Inc. (Visa Europe’s fees have historically been around 35% lower than those charged by Visa Inc.) and, as a result, by MasterCard.

Project Monnet was the prevailing force between 2008 and 2012. Originally championed by the European Commission and the ECB along with German and French banks, this initiative sought to create, alongside the leading European banks, the first standard European card accepted throughout the EU, creating an internal market for card-based payments in Europe in parallel. At the time, the banks were contemplating maintaining their co-badging arrangements with the international networks to ensure acceptance outside Europe in a context of competitive cooperation; competition in issuance, services and prices; cooperation in the areas of international acceptance, co-badging and standards. This project was interrupted in 2012 by the European authorities and may be replaced by the initiative for the creation of a pan-European instant account-to-account, i.e., IBAN to IBAN, payment scheme; this scheme will be based on the current SEPA credit transfer (SCT) scheme.

According to the Global Payment Cards Data and Forecasts to 2021 report, Visa and Mastercard accounted for 87% of the approximately 1.5 billion cards issued in Europe as of year-end 2015; moreover, the presence of exclusively domestic-branded cards is uncommon; most are co-badged with one of the international brands. As for usage, this same report states that Visa and Mastercard handled 67% (by value) of transactions paid for using European cards in 2015. This difference is relevant insofar as article 8 of the Interchange Fee Regulation (IFR) states that card schemes cannot oblige their members to “pay” for transactions that do not use the scheme; it is even more relevant in countries with co-badged debit cards.

In terms of ownership structure and governance, the international schemes have transformed radically in recent times, converting from a bank-owned mutual structure to stock market companies. Visa Europe was acquired by Visa Inc. in June 2016, upon which its members went from being owners to customers-cum-competitors, with the attendant political and sovereignty implications. Of the Spanish banks ‒ via Servired, Euro 6000 and 4B ‒ only CaixaBank had a direct interest of a little over 4% in Visa Europe.

Lastly, by no means a small number of countries are motivated to set up domestic card schemes out of concern about possible interference (geopolitical, ownership, residence, governance, sensitive data) (e.g. Russia and India).

There are, therefore, good reasons to justify, in today’s era of globalisation and digitalisation, the development by European countries of new domestic card schemes, which should be supported and used by the continent’s banks, in parallel to continuing to participate actively in the international schemes. Spain is no exception in this respect, as it is equipped to counteract the competitive pressure exerted by the large-scale multinational card operators. Against this backdrop, on December 21

st, 2016, the three national schemes (Servired, 4B and EURO 6000) entered into a merger agreement which is expected to result in the creation of a new company in March 2017

[10], subject to authorisation by the anti-trust authority (CNMC), Bank of Spain (which supports the initiative along with the ECB) and the Ministry of the Economy. All signs suggest that by the end of this year, Spain will have a single payment scheme to manage transactions performed using national cards.

In addition to growing international competition, an enhanced ability to innovate locally and lower transaction costs, the trend toward the bundling of multiple payment methods (cards and account-to-account payments) in order to offer retail customers a multi-channel value proposition may be more easily implemented by domestic schemes, which enjoy closer relations with the domestic clearing houses (the SNCE in Spain).

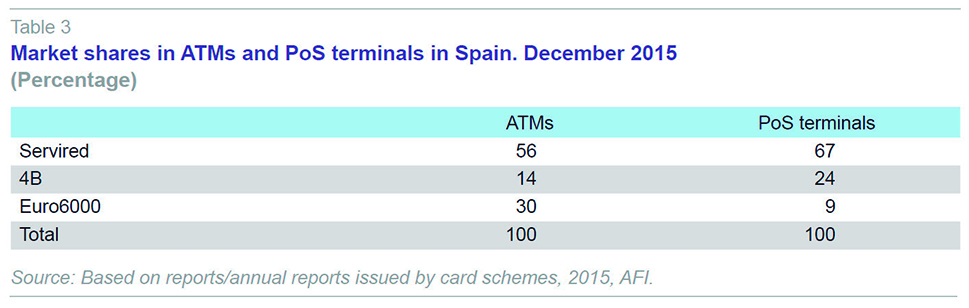

The acquiring business: ATMs and PoS terminals

Spain has close to 51,142 cash machines (ATMs) and 1,647,646 point-of-sale (PoS) terminals (twice as many as were installed in 2002) as of the end of the third quarter of 2016, according to Bank of Spain figures.

Today, the merchant acquiring business in Spain is divvied up between two groups of entities: (i) the global monoliners, which began to operate in Spain in 2012 thanks to major acquirers such as Banco Santander (which struck a joint venture with Elavon Merchant Services for the development of the acquiring business in Spain; Caixabank (Global Payments); Banco Popular (Evo Payments); and (ii) BBVA, Banco Sabadell and Bankia, which retain control over either end of the card-based payment industry: issuance and acquiring at merchants and ATMs alike.

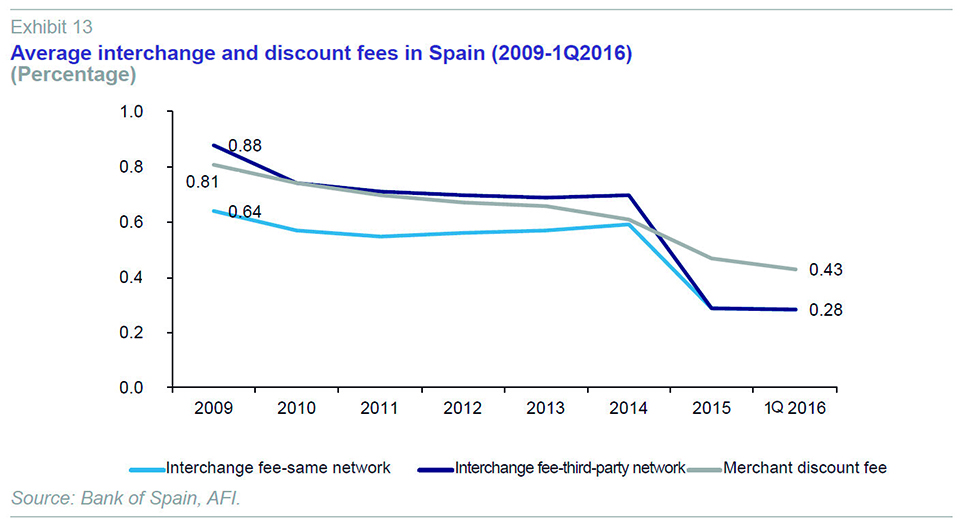

Having become less attractive in Spain at the start of this century, the acquiring side of the business has managed to find its way back to profitability thanks to the IFR, in fact emerging as one of the most attractive markets in Europe (partly because it pioneered its implementation, 15 months ahead of the deadline) for penetration by European merchant acquiring service providers not physically established in Spain.

Foreseeably, at least for debit transactions, interchange fees will remain among the lowest in Europe (recall that in Spain there is an additional limit on that stipulated in the IFR ‒ 0.2% of the transaction value and 0.1% for payments under 20 euros ‒ 7 euro cents for the entire transaction), so that the Spanish merchant acquiring business should remain attractive.

The new platform expected to emerge in 2017, following the announced merger of the three Spanish card schemes and the possible creation of a domestic debit card network that could conceivably get into the account-to-account (A2A) acquiring business (electronic card-free payments), will attempt to go head to head with third-party providers authorised under the Payment Services Directive in the single euro payments area (SEPA).

Conclusions

Payment habits at small retailers/merchants are shifting in the expected direction but not at the expected speed. The fact that Spaniards still use cash more often than card-based payments, that one in four still only use cash and that just 7% pay for their purchases only with cards suggests that there is still a long way to go in terms of encouraging card usage, particularly in small-sized retailers and, generally speaking, for micro payments.

Mass adoption of card-based payments (whether physical or virtual) or A2A electronic payments as soon as this segment develops acquiring solutions currently faces obstacles that need to be pinned down from the standpoint of all the intervening parties. In a nutshell, it remains to be determined whether or not Spain’s relative failure to wholeheartedly embrace e-payments is the result of preferences or rather existing impediments in the electronic payments market.

Notes

Whether or not to establish a minimum charge for card payments is a merchant decision that warrants close attention to see if it is a financially smart move or whether it is the result of force of habit and/or a lack of information about the real costs associated with each payment method (card vs. cash).

Created in 2002 with 67 founding members, among which BBVA.

The European schemes in existence at present are limited to their respective domestic markets; they do not have widely known or accepted brands, as they have traditionally operated under brand licensing agreements with the leading international networks. This is true of Carte Bancaire (France, 1984), Multibanco (Portugal, 1985), GiroCard/ZKE (debit only; Germany, 2007); PagoBancomat (debit only, Italy, 1986) and Dankort (debit only, Denmark).

The Switch scheme was sold to MasterCard in 2002.

Outside of Europe it is worth highlighting the recent creation of new domestic card payments schemes in Brazil, India, Nigeria and Russia.

For example, chip cards were pioneered in France, while Portugal’s Multibanco ATM network stands apart for its superior functionality relative to the ATM networks in neighbouring countries.

There are other discrepancies in the existing payment card schemes in terms of how they work and their price patterns: (i) fees / commissions for small merchants versus large merchants: in international networks, small merchants pay 60%-70% more fees than large merchants; in national schemes, this difference narrows to 6%-7%; (ii) higher fees charged to businesses in certain sectors, there being a relationship between discount fees and the margins of the businesses bearing them; (iii) a direct correlation between discount fees and interchange fees: on average, the countries with higher interchange fees also present higher merchant discount fees, demonstrating that interchange fees (the only fees regulated in SEPA) are passed along to merchants via the discount fee.

See the annual reports of the Spanish schemes: Servired, 4B and EURO 6000. This has changed with effectiveness of article 8 of the Interchange Fee Regulation (IFR) in June 2016; however, until then, the international schemes were charging for processing 100% of transactions performed using cards carrying their brands, irrespective of whether they were domestic or international transactions.

A company headquartered in Delaware (US) which operates from London.

According to articles published online, the new company will be approximately 66%-owned by the members of Servired (whose main shareholders are BBVA, CaixaBank, Bankia and Sabadell); 20% by the representatives of 4B (Santander, Popular and Banca March); and 14% by those of Euro 6000 (Unicaja, Ibercaja, Kutxabank, BMN, Liberbank, Evo Banco and Abanca), with the board seats divided up as a function of each entity’s stock of issued cards.

Verónica López Sabater and Diego Vizcaíno Delgado. .F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.