Three debates over European monetary policy

Issues relating to negative contingencies, the transmission of monetary policy decisions to the real economy, and the deployment of other macroeconomic policy instruments are at the heart of the current debate over the ECB’s monetary policy. If the institution is to overcome these challenges, it will need to address the timing and content of monetary policy and the uneven effects of monetary accommodation on banks, as well as convince governments to engage in fiscal stimulus.

Abstract: The deeper debate about the most recent decision to loosen European monetary policy centres around when monetary instruments should be used to respond to negative contingencies, how monetary policy decisions are transmitted to the real economy, and how other macroeconomic policy instruments can be brought into the mix. In terms of negative contingencies, the ECB’s Governing Council has expressed concern that the negative deposit rates and asset purchases may be close to an inflection point beyond which the costs of the policy change would outweigh the benefits. This challenge is complicated by the fact that European private banks are not all equally exposed to central bank credit, which means that the costs and benefits of monetary accommodation are unevenly distributed. Lastly, there is the struggle to address the consequences of the monetary transmission mechanism that creates differences traced back to structural factors, which are more difficult to ignore in times of relative stress. Going forward, incoming ECB President Christine Lagarde will need to forge a new consensus on the timing and content of monetary policy and on the implications of Europe’s existing monetary transmission mechanism. She will also need to encourage those national governments with fiscal space to become more active in their use of fiscal policy, and she will need to start a conversation about what are the alternatives that are available in the event that no consensus is reached within the eurozone countries on further policy actions and/or that national governments provide insufficient fiscal stimulus.

Introduction

The decision of the European Central Bank’s (ECB) Governing Council to loosen its monetary policy stance on September 12th, 2019, has ignited a very public debate about the costs and benefits of unconventional monetary policy within the European central banking community. This debate is not simply a question of rich versus poor, creditor versus debtor, or north versus south. Indeed, the superficial divisions often used to frame the debate tend to gloss over and distract attention from more fundamental concerns.

The deeper conversation is about when monetary policy should be used to respond to negative contingencies, how monetary policy decisions are transmitted to the real economy, and how other macroeconomic policy instruments can be brought into the mix. None of these issues has a clear solution and each reveal powerful assumptions about how macroeconomic policies and macroeconomic performance interact. The new leadership of the ECB will inherit a major intellectual challenge guiding this conversation toward consensus – particularly given the content of the recent policy decision.

Uncertainty, confidence, and timing

The debate about negative contingencies arose in the monetary policy accounts for the Governing Council meetings held in April and June 2019. The challenge raised in both meetings was to bolster market confidence in the face of uncertainty. In the April meeting, the ECB’s outgoing Chief Economist, Peter Praet, noted the potential for a difficult British exit from the European Union or trade conflict between the United States and China to depress business confidence in Europe – and in Germany in particular.

[1] Whether such things will ultimately come to pass is less important than the rising possibility that they might happen and the inherent difficulty in anticipating how they will impact productive investment. Hence, the more these issues are present in the minds of the business community, the less willing that community will be to undertake investment and the more likely it becomes that economic performance across the euro area will slow down under the influence of this uncertainty. Incoming Chief Economist Philip Lane reiterated these concerns in his presentation to the Governing Council in June.

[2] He enumerated a list of contingencies that included Brexit, trade wars, and a general cooling down of emerging market economies, to suggest that their impact on the confidence of the business community was already sufficient to warrant some response.

The difficulty within the Governing Council was to decide what that response should be. That response has a specific temporal dimension. As the accounts of the June meeting reveal, members of the Governing Council recognized that the ECB’s monetary policy was already very accommodative. The main policy rates were at the zero lower bound, the deposit rate was negative, the Governing Council was committed to reinvest the principal of any bonds already held on the ECB’s balance sheet, and they had planned a new round of Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations to roll out in September 2019 in order ensure that banks retained continuous access to net stable funding. Hence, the questions the Governing Council faced was whether this level of accommodation was sufficient; whether it would help to reassure market participants that such accommodation will extend into the foreseeable future; whether it would be necessary to add to the accommodative policy stance pre-emptively; or, whether it would be sufficient to underscore that all policy instruments remain available for use.

These last two temporal elements are in tension because of the policy context. Participants in the meetings expressed concern that the settings on the instruments may be close to an inflection point beyond which the costs of the policy change would outweigh the benefits – either because the costs would increase or because the influence of the policy change on macroeconomic performance would diminish. Thus, adding to the accommodative stance pre-emptively could undermine the credibility of statements that all instruments remain available for use. In the end, both meetings resulted in a subtle change for the ECB’s forward guidance – acknowledging that the policy is already accommodative and underscoring that this accommodation would remain in place so long as necessary. This shift left unaddressed the question about whether to use the instruments pre-emptively or to hold them in case of need.

Any ambivalence as to whether the Governing Council should add accommodation pre-emptively or hold in reserve the possibility to extend the policy later lasted through the July meeting.

[3] That is when the Governing Council instructed its policy committees to draw up arrangements for the further reduction in the deposit rate, the exclusion of some part of excess reserves from negative interest rate charges, and the restarting of net purchases within the large-scale asset purchasing program – meaning purchases beyond the reinvestment of maturing assets on the ECB’s balance sheets. The accounts of that meeting are interesting because of the number of occasions where the record points out that credit conditions are lax, that they have eased since the start of the year, and that the evidence suggests that banks are passing lower borrowing costs along to non-financial corporations. Hence, while the record makes clear that uncertainties are increasing and inflation expectations are falling, what remains ambiguous is the extent to which the Governing Council can improve macroeconomic performance beyond providing reassurance that monetary policy will remain accommodative and that the ECB can inject further liquidity should conditions worsen significantly.

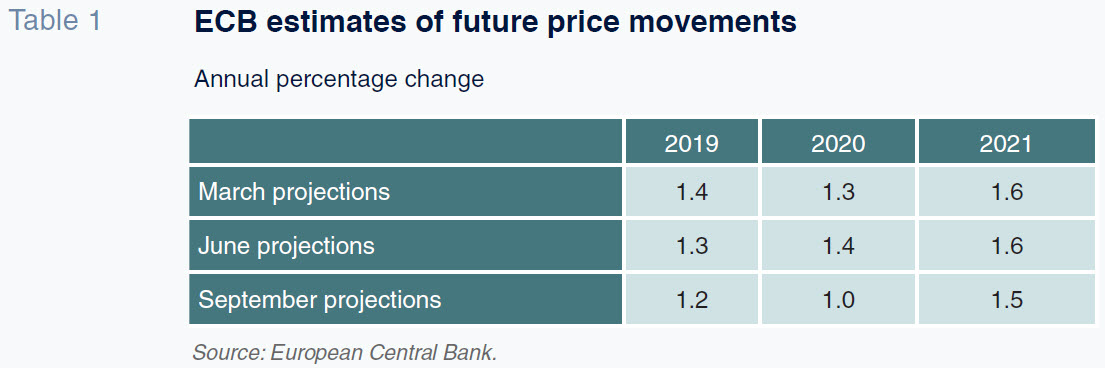

That ambiguity dissipated on September 12

th. ECB President Mario Draghi accepted that the policy instruments may be at an inflection point. Nevertheless, he argued that the faster-than-expected deterioration in economic performance coupled with the increased risk that external factors like a ‘hard Brexit’ would create an external shock necessitated immediate action. Certainly, the evidence for deterioration in inflation expectations exists. Both market-based and survey-based measures of future price increases headed in the wrong direction. Meanwhile, the ECB’s own estimates of inflation over the next three years shifted significantly, particularly with respect to the coming year (Table 1). The euro area is not in recession, but a strong deceleration is underway and the ECB is not meeting its inflation target.

The response from the Governing Council in its September monetary policy meeting was to lower the deposit rate, exempt some excess reserves from the negative deposit rate, restart net asset purchases, and improve the conditions surrounding the new allotment of targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). The question is whether and to what extent further scope for monetary accommodation exists beyond these changes. If it does not, then the hope has to be that this strengthened accommodation will provide a sufficient buffer for liquidity conditions in the event that some negative shock to performance takes place. For those voices that subsequently came out against the policy change, the possibility that the ECB might have expended the last of its ammunition constitutes a problem. Whatever the current state of macroeconomic conditions, the evidence from credit markets still pointed to lax borrowing conditions and ample monetary accommodation. [4] Weakness may lie on the demand side and yet loosening monetary conditions in the absence of demand for investment is unlikely to be effective – apart, perhaps, from the short-term boost to confidence that comes from seeing the ECB move into action. Moreover, or so the argument runs, any psychological boost to be had from further accommodation should be held in reserve to offset (or push back against) a potential change in market sentiment.

The transmission of monetary policy

This question about timing connects to a debate about the monetary transmission mechanism – which is the set of relationships that links a change in the policy rates or the ECB’s balance sheet to more general macroeconomic conditions. This debate has been very well covered by Miguel Carrión Àlvarez (2019). What Carrión shows is the complex manner through which the different policy instruments both create and redistribute the credit of the European Central Bank. The creation of central bank credit takes place when the ECB purchases privately held assets as part of its asset purchasing program. Initially, this credit shows up as deposits held by banks with the ECB or one of its corresponding institutions – collectively known as the Eurosystem. The challenge is therefore to create incentives for the banks to withdraw those deposits in order to fund some other private asset or investment opportunity – which is what stimulates economic performance. That challenge is complicated by the fact that whoever receives the money withdrawn from the Eurosystem by one bank is only going to deposit that money into another – which means eventually it winds up back at the ECB or one of its corresponding institutions.

The incentives for banks to withdraw deposits held in the Eurosystem come from the demand for borrowing in the private sector and from the deposit rate offered by the ECB. When this deposit rate is negative, it constitutes a tax on private banks. The higher monetary policymakers set that negative rate, the larger the tax and the greater the incentive for banks to recycle any deposits they hold in the Eurosystem through the private sector. Creating central bank credit through further asset purchases constitutes part of the transmission mechanism; creating the incentives for private banks to cycle that central bank credit through the private sector by lowering the deposit rate to create a greater tax on excess deposits is another. Who pays the tax differs depending upon who ends up accumulating central bank credit, but the amount of the tax charged by the Eurosystem (of central banks) on the European private banking sector does not.

The problem for the Eurosystem is that European private banks are not all equally exposed to central bank credit. This tends to vary by country. The Governing Council’s decision to exempt a large share of central bank deposits from the negative deposit rate has implications that vary by country as well. The new policy compensates those banks that have generous access to credit, but at the cost of lowering the incentives for those banks that have less access to central bank deposits to lend to the private sector. The provision of long-term refinancing operations with subsidized borrowing costs for banks (TLTROs) that meet set targets for private sector lending adds to the balance sheet of the ECB and helps to equalize access to central bank credit while at the same time strengthening the incentives for those banks that access such facilities to recycle that credit through the private sector. By implication, this policy also adds to the overall tax charged against the banks for holding reserves in ways that vary from one country to the next. The conclusion to draw from this analysis is that the costs and benefits of monetary accommodation are unevenly distributed no matter how the monetary accommodation is structured. The only pieces missing from Carrión’s analysis of the new policies are: (a) the mechanism that connects the more attractive banks for savers to those that have more difficulty getting access to central bank credit; and, (b) the possibility that either banks or actors in the private sector might take some of the liquidity created by the Eurosystem out of the euro area via the exchange rate. These elements are worth noting because they tend to fuel the controversy over the monetary transmission mechanism.

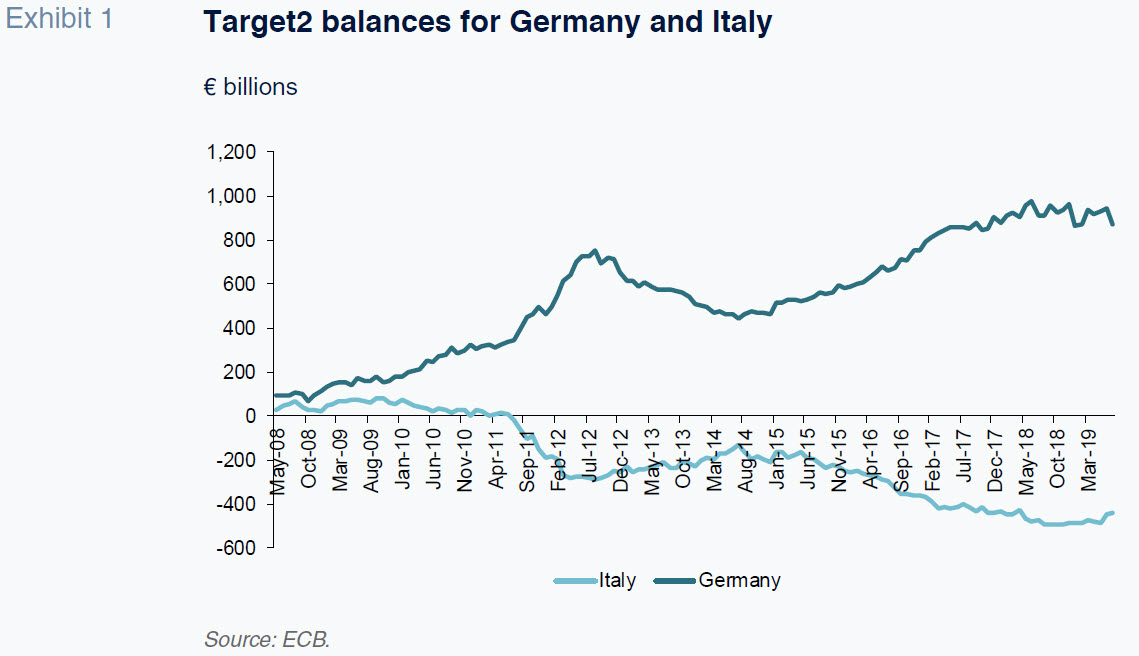

Target2 is the mechanism that connects the banks in those countries that are more attractive to savers with the banks in those countries that have more difficulty gaining access to central bank liquidity. The notion of ‘attractiveness’ is crucial here. This is not a question about which countries save more and which save less; it is a question about which countries are more likely to ‘attract’ savings from across the European financial space. Countries that are more attractive for savers receive surplus deposits and show a positive balance in their overall relationship with the Eurosystem as they build up reserve holdings; countries that are less attractive for savers require access to central bank liquidity and show a negative balance as they borrow against collateral. Moreover, both the large-scale assets purchased by the ECB and the targeted long-term refinancing operations tend to exacerbate these positions as central bank credit is created and then recycled through actors in the private sector.

[5] A quick comparison of the Target2 positions for Germany and Italy is illustrative; just look at what happens after the ECB started experimenting with unconventional monetary policy settings in the spring of 2014 (Exhibit 1). As a result, the operation of these policies creates the impression that one group of countries is lending into the Eurosystem the same funds that another group of countries is borrowing. In this way, the same structural elements that make some banks in some countries more attractive than others from a savings perspective, appears to create another form of inequity (Schelkle 2017, Chapter 9).

The exchange rate is the mechanism that connects the European financial system to the outside world. Both banks and private sector borrowers can use the credit they access to purchase assets abroad. When they do so, they draw down on the overall pool of liquidity available in the euro area because they trade domestic credit for foreign exchange held by the Eurosystem, putting downward pressure on the domestic currency, increasing competitiveness. For national economies that have a relatively straightforward commercial relationship with the outside world, such downward pressure on the exchange rate constitutes another branch of the monetary transmission mechanism.

Unfortunately, the effectiveness of the exchange rate channel is less evident for national economies with more complex commercial relationships – particularly when the interaction between central banks across countries is taken into account. This is one of the points Australian Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe pointed out in a widely cited speech at the August 2019 monetary symposium at Jackson Hole.

[6] The currency may depreciate without offering much in terms of macroeconomic stimulus, particularly if domestic investment is held down by uncertainty (see above). In such a case, export driven economies that might automatically be assumed to benefit from competitive movements in the exchange rate might find little to celebrate in seeing domestic savings converted into foreign assets. Meanwhile, those economies that tend to rely heavily on imports find their costs rising with any downward movement in the euro.

[7] The result in both contexts is another form of structural inequity that can give rise to very different interpretations of the costs and benefits of an accommodative monetary policy.

Monetary policy and fiscal policy

The monetary transmission mechanism has unintended consequences that create differences traced back to structural factors related to market perceptions of creditworthiness and commercial relations with the outside world. In turn, these structural differences can foster differences in perception. During normal times, when monetary policy is part of a wider framework of macroeconomic instruments and when the settings applied to monetary policy instruments are well understood, such differences are relatively easily overlooked. In less normal times, when monetary policy assumes much of the burden for macroeconomic stabilisation and when the settings on monetary instruments are more difficult to interpret, the differences in perceptions increase in significance.

The big question is how to diminish the significance of these differences. One possibility would be to find some way to increase monetary accommodation without running in the first instance through the banking channel. If monetary authorities could give central bank credit directly to private sector actors, that would offer one solution. However, such actions would not eliminate the pooling of deposits on the balance sheets of specific banks or in the Target2 positions of specific countries nor would they eliminate the exchange rate impact. But they would make it easier to ensure that the initial injection of liquidity was evenly distributed. This would also make it easier for the Eurosystem to avoid creating distortions in the secondary markets for those instruments involved in the asset purchasing program. This is the ‘helicopter money’ solution. As Mario Draghi made clear in the September 12

th press conference, however, this solution is essentially a form of fiscal policy – and so does not fall within the remit of the ECB.

[8]

The other solution is to encourage national governments to engage more actively in providing fiscal stimulus both to strengthen the euro area economy and to take some of the burden off monetary policy (and so lessen the need for extensive monetary accommodation). The difficulty with this solution is that the ECB has little leverage over national policymakers. On the contrary, so long as the Governing Council retains room for maneuver, national policymakers have an incentive to rely on the ECB to shoulder responsibility for macroeconomic stabilisation. Much of Draghi’s recent press conference can be read as an expression of frustration about this situation. Time and again Draghi made it clear that the ECB has done its part to stabilise macroeconomic performance in the euro area, that monetary policy without fiscal policy will ultimately prove to be ineffective, and that those national governments that have room to undertake fiscal expansion also have an obligation to add their weight to the stimulus package. It is unclear whether this rhetoric has had any impact – or whether the weeks that remain of Draghi’s mandate are time enough to drive the argument. This leaves open the possibility that –whether intentionally or not– Draghi may have used up the ECB’s room for maneuver in terms of monetary policy, leaving national governments with a stark choice between using fiscal policy to stabilise macroeconomic performance or allowing Europe’s macroeconomy to fluctuate without further stimulus.

Whatever room may be left for the ECB to add to its monetary accommodation, it appears evident that Mario Draghi’s successor, Christine Lagarde, is determined to promote a more balanced macroeconomic policy mix. In her testimony before the European Parliament, Lagarde also pledged to conduct a review of the ECB’s approach to its price stability mandate.

[9] If she is to be successful in this endeavor, it will not be enough to bridge the gap between creditor and debtor, rich and poor, or north and south. Lagarde will need to forge a new consensus on the timing and content of monetary policy, on the implications of Europe’s existing monetary transmission mechanism, and on the alternatives that are available in the event that national governments refuse to play their part. This is a complex agenda. She will benefit greatly if the euro area can move toward a more normal framework for monetary policymaking and away from crisis management. Hopefully this latest round of accommodation will be sufficient to move the euro area toward a period of greater stability. If that does not happen, these three debates about European monetary policy will be at the centre of attention, and Lagarde’s ability to convince national policymakers to engage in fiscal stimulus may prove decisive.

Notes

‘Account of the Monetary Policy Meeting, 9-10 April 2019,’ (Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 23 May 2019). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/accounts/2019/html/ecb.mg190523~3e19e27fb7.en.html

‘Account of the Monetary Policy Meeting, 5-6 June 2019,’ (Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 11 July 2019). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/accounts/2019/html/ecb.mg190711~16eb146254.en.html

Other studies (e.g. Alves, P. et al., 2018). give a different explanation to Target 2 balances, linking them to ECB quantitative easing measures.

Patrick Honohan and Philip Lane (2003, pp. 74-77, 95) noted the disparate influence of exchange rates on relative cost structures early in the life of the euro area.

References

ALVES, P., DEL RÍO, A. and MILLARUELO, A. (2018). The increase in TARGET balances in the euro area since 2015. Bank of Spain. December 5

th, 2018.

CARRIÓN, M. (2019). The ECB’s Decisions,

Funcas Europe (13 September 2019). Retrieved from:

https://www.funcas.es/funcaseurope/The-ECBs-decisions.

HONOHAN, P. and LANE, P. (2003). Divergent Inflation Rates in EMU. In: R. BALDWIN, G. Bertola and P. Seabright (Eds),

EMU: Assessing the Impact of the Euro, pp. 67-95. London: Blackell Publishing.

SCHELKLE, W. (2017).

The Political Economy of Monetary Solidarity: Understanding the Euro Experiment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Erik Jones. Professor of European Studies and International Political Economy and Director of European and Eurasian Studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies