The new European Bank Resolution Directive in the face of MREL adaptation

In order to align itself with the new international paradigm, the European Union has amended its Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) to adapt its own rules on loss absorbing standards. These regulations set the minimum requirement for own funds and liabilities capable of absorbing losses by entities and are expected to influence the size and types of instruments issued by banks.

Abstract: With an eye to preventing the use of public funds to shore up weakened financial institutions, there is now an international consensus that entities must be equipped to ‘bail in’ their losses in an orderly manner. In this context, in 2015, the Financial Stability Board approved the total-loss absorbing capacity (TLAC) standard, endorsed by the G20. TLAC stipulates that global systemically important institutions (G-SIIs ) must hold a minimum level of own funds and liabilities capable of absorbing losses. Following approval of the TLAC at the international level, the European Union has revised its bank resolution directive to adapt its equivalent concept, the Minimum Requirement for own funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL), accordingly. Significantly, MREL regulations capture more financial institutions than the TLAC, prioritise equity, subordinated debt and non-preferred senior debt instruments to meet the new capital requirements and set specific minimum thresholds for larger-sized entities. Consequently, this new regulation will influence the size and types of instruments entities issue.

[1]

Background: The bail-in concept and loss-absorbing capacity requirements

In light of the massive amounts of public funds mobilised to tackle the financial crisis of 2008, a global paradigm shift has taken place regarding the management of ailing financial institutions. The new international consensus – first reached by the G-20 and later by the European Union (EU) – is that entities must be equipped to absorb or ‘bail in’ their losses in an orderly manner to minimise the use of public funds. As such, the banks are required to build up a sufficient level of own funds and liabilities to absorb any losses they may incur, to ensure their viability, and to reduce the negative impact on financial stability.

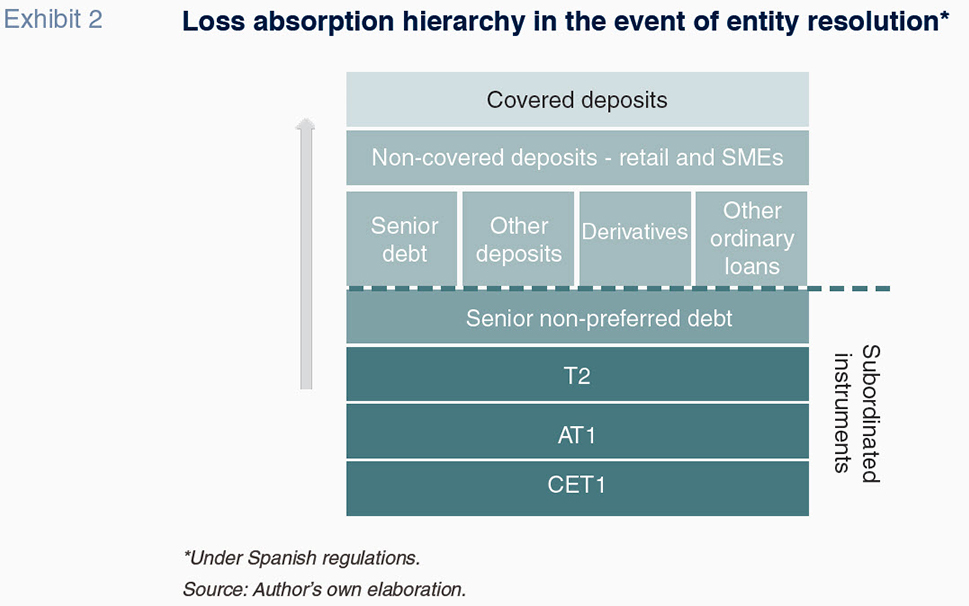

If an entity goes through a resolution process, the losses will be assigned to its creditors. However, given the specific nature of the banking business and the entities’ liability structure, this may impose losses on deposit holders, which could undermine confidence in the banking system. To prevent this, banks are obliged to increase the percentage of funding held in the form of debt and equity. Unlike deposits, those liabilities are typically held by professional investors and tend not to present as dual creditor-customers.

From the TLAC to the MREL

In 2015, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) approved the total loss absorbing capacity standard (TLAC) endorsed by the G-20. The standard stipulates that the global systemically important institutions (G-SIIs) hold a minimum level of own funds and liabilities capable of absorbing losses.

That level was set at 18% of total risk-weighted assets (RWAs) in 2022, to be met mainly with equity and subordinated debt (recall that under the Basel requirements banks are already required to hold capital equivalent to at least 8% of their RWAs in addition to the so-called pillar 2 capital requirements and capital buffers).

Although the EU formulated a comprehensive regulatory and institutional framework addressing bank resolution in 2014 (reinforced for Banking Union in the eurozone), approval of the TLAC standard has prompted the need to revisit the European equivalent, the Minimum Requirement for own funds and Eligible Liabilities (the MREL). The TLAC lacks any legal weight until each country adopts it as binding resolution. The European Union is currently undergoing this process as part of this reform procedure.

Nevertheless, the recently approved amendments to the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), known as BRRD2, coupled with the new Capital Requirements Regulation, go beyond the mere incorporation of the TLAC standard.

The main differences between the TLAC and the MREL are as follows:

- The TLAC only affects the G-SIIs, whereas the MREL is binding for all EU financial institutions.

- The minimum TLAC requirement is the same for all entities (18% of RWAs), whereas the MREL is set entity by entity, based on the formulae and valuations contemplated in the BRRD2.

- The TLAC must be met through subordinated instruments (equity, subordinated debt and non-preferred senior debt, with minimal exceptions), whereas the MREL can be met in part by other instruments.

In short, while the initial goal was to transpose the TLAC into EU legislation and facilitate the G-SIIs’ simultaneous compliance with both regulations, in practice the new MREL has emerged as a more exacting instrument than the TLAC, as it will require a significant number of entities to fulfil a requirement of own funds and eligible liabilities higher than 18% of RWAs. In practice, these new requirements represent progress in reducing risk in the EU’s financial system. However, it will mean a considerable compliance effort on the part of the banks.

Financial instruments eligible for the MREL

The MREL must, in principle, be met from equity, subordinated debt, senior debt (preferred or non-preferred) and uncovered non-preferred deposits unbreakable before one year. It cannot be met from covered deposits, derivatives or secured instruments.

However, the BRRD2 requires banks to meet the MREL with a significant percentage of subordinated instruments (those that in insolvency proceedings would absorb losses before excluded instruments): equity, subordinated debt and non-preferred senior debt. The subordination requirement stems from the fact that those instruments are easier to bail in and less prone to litigation than other liabilities (senior debt and corporate deposits) that rank

pari passu with excluded liabilities, such as derivatives.

Elsewhere, the BRRD2 implements the TLAC criteria for eligible instruments. For example, it permits the use of structured notes; however, to ensure that the presence of embedded derivatives does not erode their loss-absorbing capacity, the amount of principal repayable at maturity must be fixed or increasing.

It is also worth noting that to ensure the liabilities are available for write-down and conversion if necessary, eligible debt instruments must have a residual maturity of more than one year and the holder of that debt cannot have the right to redeem it within that period.

In addition, the BRRD2 reinforces the obligation to include in any instrument subject to the laws of a country outside the EU a clause that consents to potential write-down and conversion powers under European bank resolution legislation for them to compute for the MREL (albeit recognising that in some circumstances it may be impossible to include that clause, such as in a public tender).

As for the potential sale of such instruments to retail customers, the European Parliament tightened the disclosure and disclaimer obligations for banks. The new legislation moves beyond MIFID II in terms of retail investor protection by extending the requirement to carry out a suitability test when selling eligible subordinated liabilities (mainly non-preferred senior debt) to retail investors. The Member States are also entitled to extend that requirement to other instruments eligible for the MREL.

The BRRD2 places restrictions on the volume of MREL instruments that can be placed with retail customers, entitling the national competent authorities to opt between imposing a 50,000 euro minimum denomination for MREL instruments or to limit the percentage of retail financial portfolios that can be invested in eligible liabilities to 10%, in addition to a minimum initial investment of 10,000 euros. All of these requirements will apply to instruments issued from December 28th, 2020.

Characteristics of the MREL: Calibration and subordination

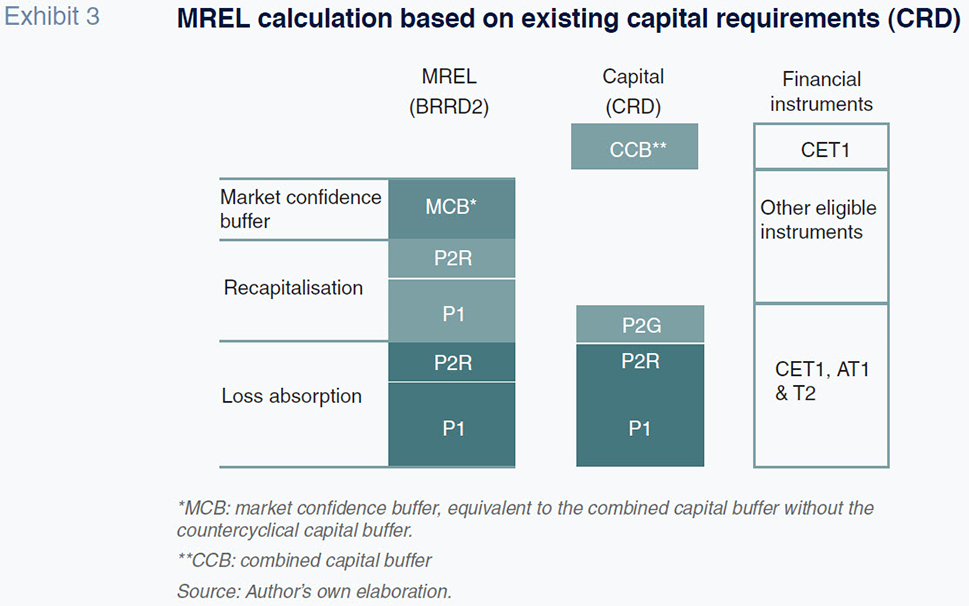

The rationale underpinning the MREL calculation is that it should be sufficient to enable the absorption of potential losses and provide a bank with enough capital for it to continue operating in accordance with applicable capital requirements. A more detailed calculation formula has now been established at the directive level (and at the regulatory level for Banking Union purposes), whereas previously the resolution authorities (those responsible for setting the MREL entity by entity) had more freedom.

The MREL is made up of a loss-absorption allowance (LAA) and a recapitalisation allowance (RCA), plus a market confidence buffer (MCB):

The basic formula applicable to all entities builds from the existing capital requirements as per the related directive (CRD) and is expressed as a percentage of risk-weighted assets (RWAs) and total risk exposure (using the leverage ratio formula), in keeping with the TLAC and Basel standards.

The instruments used by the banks to meet their capital requirements will also be eligible for MREL purposes, except for the combined capital buffer required under the CRD, which will have to be calculated separately.

Upward and downward adjustments can be made to this basic formula for each entity, primarily through the recapitalisation component, considering that:

- The recapitalisation requirement can be expected to decline as the entity emerging from a resolution will have a smaller asset base following the materialisation of losses and the resolution actions;

- Resorting to resolution tools other than the bail-in (sale of business tool or the creation of bridge bank or asset management vehicle) could also reduce the recapitalisation requirement;

- If the strategy followed to address the crisis is liquidation and not resolution, the resolution authority can decide that it is not necessary to fulfill the recapitalisation allowance.

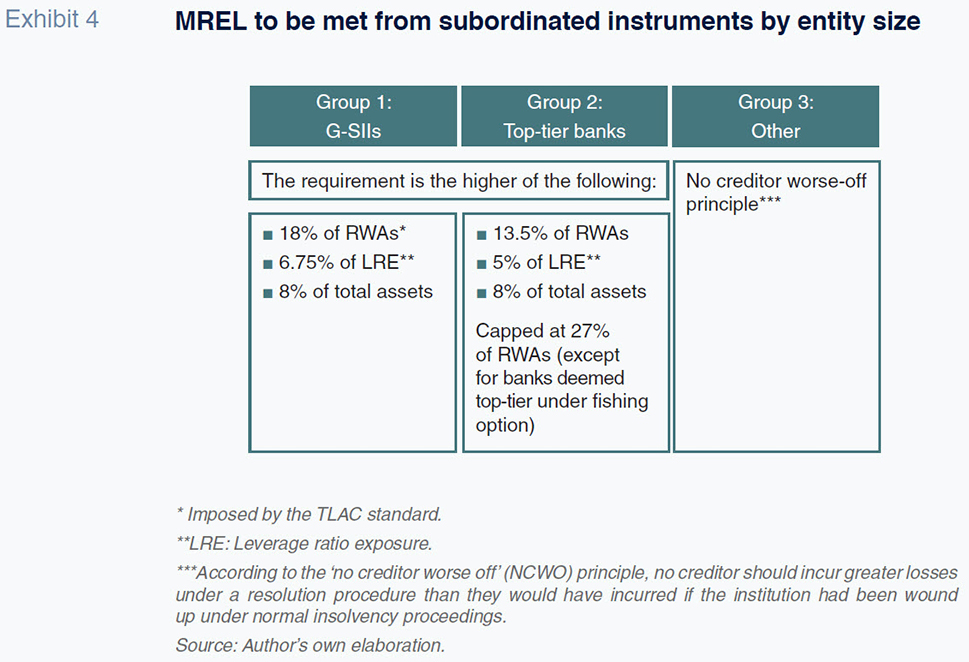

However, the real significance of the Directive lies in the requirement of binding minimum percentages to be covered from subordinated instruments (equity, subordinated debt and non-preferred senior debt) for the larger-sized entities. For this purpose, the Directive has classified the banks as follows:

- Group 1: G-SIIs (the original targets of the TLAC standard).

- Group 2: Large or ‘top-tier’ banks- resolution groups with assets of over 100 billion euros.

- Group 3: Other banks.

However, the resolution authorities can decide that certain group 3 entities receive top-tier equivalent subordination treatment if it is considered probable that their non-viability could pose systemic risk. This is called the ‘fishing’ option.

In addition, for up to 30% of the G-SIIs, top-tier banks, and those banks captured under the fishing option that also fall under the responsibility of a single resolution authority, the subordination percentage can be increased above those thresholds (maximum of 2P1+2P2R+CCB) if there are impediments to resolvability, the entities’ resolution strategies are not credible or the entities are among the top 20% riskiest institutions within the Banking Union.

For the rest, the subordination percentage decision will be taken entity by entity on the basis of the ‘no creditor worse off’ (NCWO) principle, similarly subject to the cap described above.

Timeline for meeting the MREL

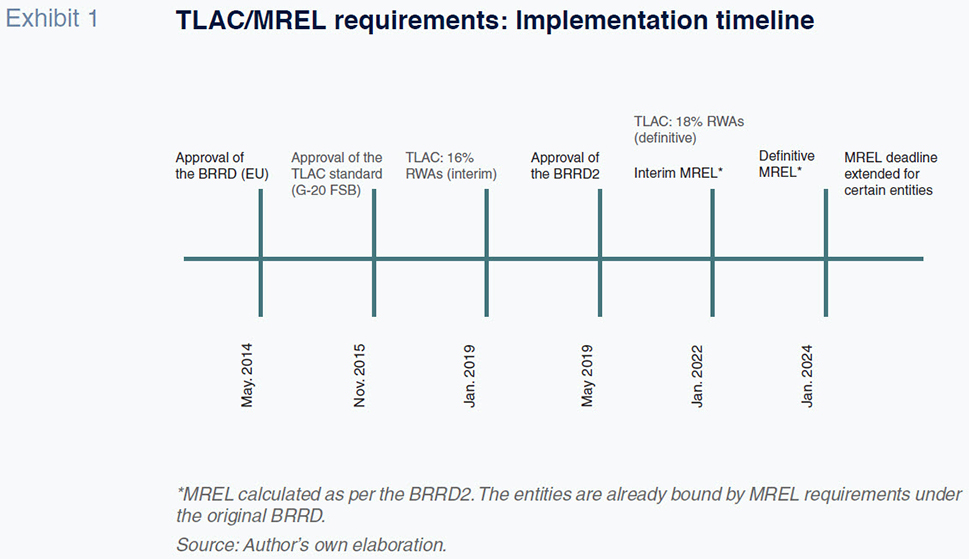

The deadline for meeting the new directive’s MREL requirements is January 1st, 2024. The resolution authorities are already imposing MREL obligations under the original directive on entities, such as the Single Resolution Board within the Banking Union.

Before that, by January 1st, 2022, the banks must meet certain interim milestones to be set by the resolution authorities. The G-SIIs, top-tier banks and those under the fishing option must meet their minimum subordination requirements by this date.

The authorities are entitled to extend the deadline beyond 2024 depending on the financial situation of the bank in question, its ability to rollover issues as they mature and their ability to meet the requirements on time. To this end, they may also consider the weighting of deposits and CET1 equity, the lack of debt instruments in their funding models, and access to capital markets for eligible liabilities.

MREL disclosure requirements and penalties for breaches

The BRRD2 obliges banks, other than the G-SIIs, to publish their MREL levels annually. The G-SIIs, subject to the TLAC standard, must do so quarterly. Note that the entities already have to publicly disclose their MREL requirements via price-sensitive notices under securities market law. However, entities whose strategy in the event of a crisis is liquidation are exempted from disclosing this information, which in practice implies giving the market additional information.

Failure to adequately fulfill the MREL could impede a bank’s orderly resolution, triggering the need to mobilise public funds or impose losses on sensitive creditors such as deposit holders. Such a situation could become a source of financial market instability. As a result, the resolution authorities need the power to oblige banks to comply with these requirements on an expedited basis.

If a bank fails to meet its MREL, the resolution authorities can prohibit them from issuing dividends and other distributions associated with CET1 and AT1 capital, as well as variable remuneration and discretionary pension benefits. The penalties can be imposed in a proportionate way as soon as the breach occurs, and after six months at the latest, barring grave financial market turbulence, among other circumstances.

These penalties are already foreseen in the event of banks’ failure to comply with their prudential requirements. Such penalties may pose a problem for banks as they could make their issues less attractive.

How will the MREL be applied to the various entities?

The banks that present the greatest systemic risk, and for which fulfilling a sufficient MREL is crucial, are often large cross-border groups with material subsidiaries within (and beyond) the EU.

This means that the total MREL that banks need to satisfy includes those amounts specified by various resolution authorities in the jurisdictions of the parent bank and its subsidiaries. The eurozone’s Banking Union has helped by unifying institutions. However, the ‘single authorities’ (ECB, Single Resolution Board) coexist with the national competent authorities, in addition to having to engage with authorities of states outside the Banking Union.

Against this backdrop, the BRRD2 urges the resolution authorities to take joint decisions. However, in the event of disagreement, the decisions of the resolution authority of the entity under its jurisdiction shall prevail.

In general, each resolution group will be obliged to meet an MREL requirement, called the ‘external MREL’, to be issued by the resolution entity (group main undertaking from a resolution perspective) and acquired by external third-party creditors.

In this respect, the BRRD2 contemplates the possibility of splitting a financial group into several parts or resolution groups, isolated from each other in the event of resolution, so as to stem potential contagion. Each resolution group must have its own external MREL. In Spain, banks such as BBVA and Santander will be subject to this arrangement known as the multiple point of entry system, due to their long-standing exposure to regions outside of the EU such as Latin America.

In parallel to the external MREL, the rest of the group entities (other than the main undertaking) must have their own MREL – the so-called ‘internal MREL’ – to ensure their loss-absorbing capacity and reduce their dependence on the parent bank. Unlike the external MREL, the internal MREL can be met using financial instruments acquired by other entities within the same group.

At the start of the negotiations, the European Commission proposed letting the European cross-border financial groups meet their internal MRELs with guarantees from the resolution entity, which would have given them greater freedom to allocate resources within the group while complying with the external MREL as a whole.

However, it failed to build the consensus needed to implement that cross-border exemption, which would have facilitated, according to its advocates, wider integration in the single market. What was allowed was an exemption from the internal MREL for group entities operating in a single country.

Exceptionally, credit institutions permanently affiliated to a central body (“cooperative networks”) will be allowed to meet their external MREL at the group level.

Other changes designed to facilitate execution of a bank resolution

The resolution authorities have been given greater powers to suspend the payment or delivery obligations of an entity under resolution. That power, sometimes referred to as ‘moratorium’ power, is designed to reduce instability emanating from an entity while resolution measures are executed. The main novelties are:

- The resolution authorities can suspend deposit withdrawals. However, that suspension will not be automatic. It will require a careful assessment (particularly in respect to covered deposits held by natural persons and micro, small and medium-sized enterprises). Alternatively, they can allow deposit holders to withdraw an “appropriate daily amount”.

- The suspension can start from when the supervisor (the ECB) determines a bank to be “failing or likely to fail”, without having to wait for a resolution decision.

- The suspension may be left in place for two business days at most (the Commission’s initial proposal was for up to five days).

Beyond the MREL

Although the requirement that the banks build up an adequate MREL should usher in greater stability in the financial system and prevent the use of public funds, the size of the MREL and the types of instruments needed to comply with it mean banks must make certain changes to their funding structures. The new requirements are having a particular impact on the size and type of securities banks issue, spurring a burgeoning market for senior non-preferred debt issues.

Elsewhere, definitive implementation of the new directive will depend not only on its transposition by the Member States (deadline: December 28th, 2020), but also the regulatory technical standards adopted by the Commission at the behest of the European Banking Authority (EBA) and how each resolution authority interprets the directive in its MREL policies and bank resolution plans.

Lastly, the new Commission will have to face the pending revision of the resolution directive in order to continue to fine-tune (notwithstanding the limited amount of hands-on experience to date) implementation of the resolution procedures and management of bank non-viability in general – key aspects of financial stability in the EU.

Notes

The opinions expressed in this paper are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinion of the Ministry of Economy and Business. The author would like to thank Sara González Losantos and Javier Ortega Castro for their contributions to the directive negotiations process.

References

BERGES, A., PELAYO, A. and ROJAS, F. (2018). Spanish banks ahead of MREL: Estimating projected issuance for compliance. Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 7, Nº 2, pp. 37-44, March.

EUROPEAN BANKING AUTHORITY EBA (2016).Quantitative update on EBA MREL report.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2019). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the application and review of Directive 2014/59/EU (Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive) and Regulation 806/2014.

Directive (EU) 2019/879 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2019 amending Directive 2014/59/EU as regards the loss-absorbing and recapitalisation capacity of credit institutions and investment firms and Directive 98/26/EC.

Regulation (EU) 2019/876 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2019 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards the leverage ratio, the net stable funding ratio, requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities, counterparty credit risk, market risk, exposures to central counterparties, exposures to collective investment undertakings, large exposures, reporting and disclosure requirements, and Regulation (EU) No 648/2012.

Marta Martínez Guerra. Senior Advisor of the Sub-Directorate General for the Legislation of Banks and Banking and Payment Services within the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Business