Bank profitability in the new monetary paradigm

In light of persistently low interest rates, increasing attention has been paid to the effects of loose monetary policy on banks’ margins. Empirical research suggests that the positive effects of reducing rates to below zero percent are outweighed by the adverse effects on bank profitability and, potentially, on overall financial stability.

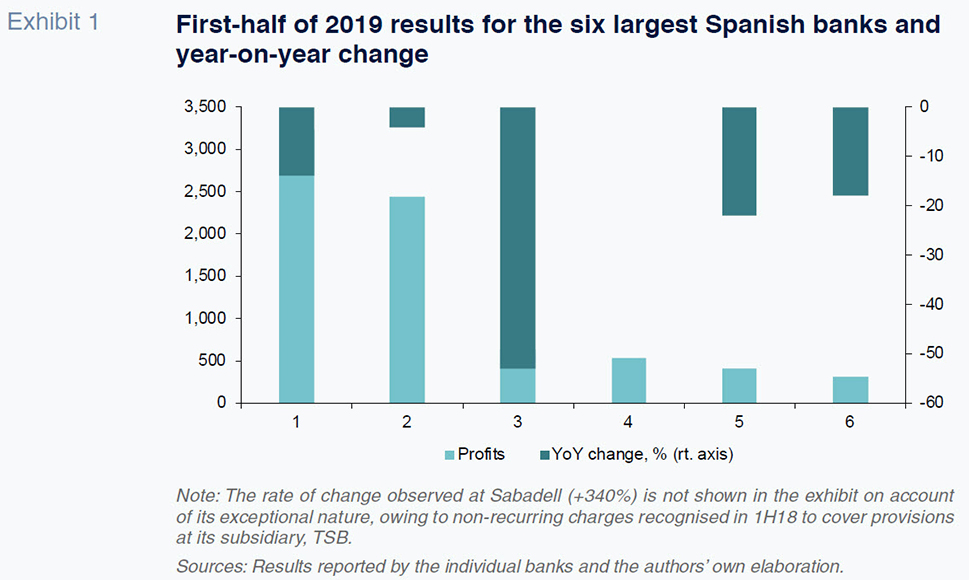

Abstract: Due to fears of recession and evidence of weak inflation, central banks returned to an expansionary monetary track in 2019. In light of this, debate has centred around the adverse impact of prolonged, low interest rates on banks’ margins. For instance, Spain’s six largest banks posted earnings in the first half of 2019 that were down 11% from the same period in 2018. While the ECB lowered its deposit rate an additional 10 basis points further into negative territory in September 2019, the central bank also introduced a tiered-deposit rate with the goal of offsetting the pressure on banks’ margins. However, this provides only partial support for bank profitability. Looking at the empirical evidence, it becomes clear that while asset non-performance improves when rates fall, the effect on net interest margins is greater, thereby reducing a bank’s profitability. Negative rates can even have the opposite effect on stimulating credit than the one intended due to their influence on markets’ expectations. More broadly, negative rates can distort yield curves, exacerbating debt accumulation and potentially impacting financial stability. Finally, they can impact exchange rates, which warrants careful consideration in the context of today’s trade tensions.

Introduction

The policy response to the financial crisis unleashed a decade ago has been predominantly monetary. This was justified by the understanding that if stimulus measures became considerable, it would be important not to leave them in place for too long in order to prevent a spike in inflation. As a result, the United Stated embarked on a period of monetary tightening in 2015, which would lead to successive rate hikes in subsequent years. Conversely, the eurozone would have to wait until 2018 to raise the possibility of a similar move. However, in 2019, those policies have been rolled back and new expansionary measures aimed at boosting liquidity and reducing interest rates are on the table. In the absence of fiscal stimulus measures on either side of the Atlantic, there is additional pressure on monetary authorities to take action. However, backtracking on the announced tightening path is tantamount to acknowledging that something may not be going as planned as regards the central banks’ projections. Furthermore, the effectiveness of expansionary monetary measures has been called into question. This is a point of contention in the eurozone where official interest rates stand at 0%, so that further cuts would result in interest rates entering negative territory.

From an aggregate perspective, the challenge with ultra-low rates is determining their effectiveness in reigniting inflation. However, it is also important to consider how negative interest rates distort financial markets, banking business and real estate services, and whether these effects are offset by the theoretical benefits derived from higher inflation. An analysis of these dynamics is beyond the scope of this article whose objective is to evaluate the impact low interest rates have on Spanish banks’ earnings by examining what leading studies and empirical evidence have to say about the effects of negative interest rates.

The banks’ aggregate earnings for the first half of the year appear to demonstrate the effect loose monetary policy has had on these institutions’ profitability. Spain’s six largest banks, whose recent results are shown in Exhibit 1, earned 7.54 billion euros in the first half of 2019, down 11% from the 8.43 billion euros reported for the same period of 2018.

As analysed in this paper, the net interest margin (the difference between revenue generated from a bank’s interest-bearing assets and expenses borne on its interest-bearing liabilities) has been particularly affected by low interest rates.

Earnings season in the Spanish banking sector was followed by important announcements by the European Central Bank on July 25th. The interest rates for refinancing operations, the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility were left unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.40%, respectively. The ECB’s Governing Council said it expects “the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels through the first half of 2020”. As for its liquidity operations, the ECB said it intends to continue reinvesting the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the asset purchase programme. It underlined the fact that the ECB stands ready to adjust all of its instruments to ensure inflation moves towards its aim in a sustained manner. That point had prompted discussion among analysts about a possible rate cut at an upcoming meeting, a move which would put benchmark rates into negative territory. For technical and practical reasons, it also implied contemplating changes to the deposit facility rate. There had also been intense debate about the possibility of a tiered system (different remuneration rates for different tranches) for those deposits in order to help alleviate bank margins. Regarding this possibility, the ECB said that “the Governing Council has tasked the relevant Eurosystem Committees with examining options, including ways to reinforce its forward guidance on policy rates, mitigating measures, such as the design of a tiered system for reserve remuneration, and options for the size and composition of potential new net asset purchases.”

On September 12th, the ECB’s Governing Council cut the deposit facility rate by 10 basis points to -0.50%. The interest rates for main refinancing operations and the marginal lending facility were left unchanged at 0.00% and 0.25%, respectively. The Governing Council said that it expects the ECB’s official interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels “until it has seen the inflation outlook robustly converge to a level sufficiently close to, but below, 2% within its projection horizon, and such convergence has been consistently reflected in underlying inflation dynamics.” It also said that “net purchases will be restarted under the Governing Council’s asset purchase programme (APP) at a monthly pace of 20 billion euros as from November 1st” and that it intends to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the asset purchase programme. Elsewhere, it announced changes in the modalities of a new series of quarterly targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) “to preserve favourable bank lending conditions, ensure the smooth transmission of monetary policy and further support the accommodative stance of monetary policy.” Lastly, the Council has decided to introduce a two-tier system for reserve remuneration whereby part of the banks’ excess liquidity holdings will be exempt from the negative deposit facility rate.

Monetary policy alone does not account for all of the pressure on bank profits. Regulation is also playing a significant role. On August 5th, the European Banking Authority (EBA) presented estimates of the EU banks’ capital requirements under Basel III. It reported that full implementation would, under “conservative assumptions”, increase the European financial institutions’ minimum capital requirement by 24.4% on average, implying an aggregate capital shortfall of 135.1 billion euros, or 91.1 billion euros in terms of common equity tier (CET1) capital. Moreover, that pressure is concentrated overwhelmingly at the large, global banks, which account for 99% of the requirement, with the medium-sized and small banks comprising 0.9% and 0.1%, respectively.

Negative rates and bank profitability

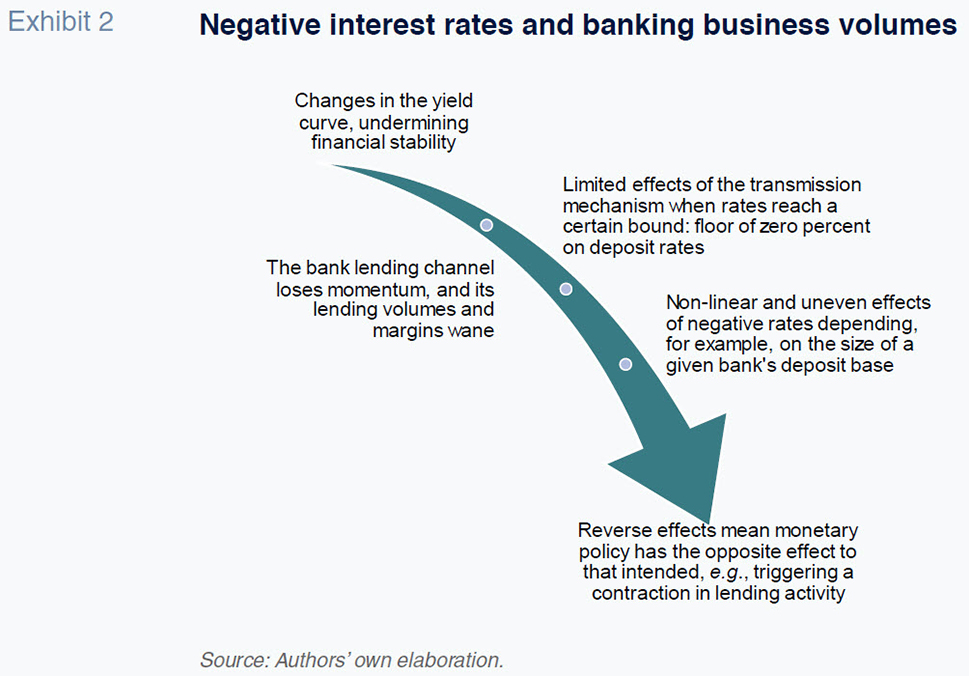

Academic and empirical research provide insight into the potential impact of negative rates on the banking sector. Exhibit 2 sums up the literature’s main ideas, which can be distilled into the following five points:

- The main transmission mechanism through which negative benchmark rates act is the yield curve. Negative rates can exacerbate circumstances where short-term rates are higher than long-term rates. This happens in part because the effectiveness of reducing rates could have a floor beyond which monetary policy becomes less effective or even ineffective (effective lower bound or ELB). Simultaneously, the market receives signals regarding the structure of debt remuneration, which adversely affects the long end of the curve.

- In a broad range of situations, bank deposit remuneration does not tend to drop below zero percent. Rarely do the banks offer their deposit holders negative rates as it is considered an anomaly that would be hard for customers to comprehend. [1]

- Several studies show that the bank lending channel becomes less effective when rates are at or near zero percent. The ECB itself has observed that lending volumes remain at modest levels despite the fact that the official rate stands at zero percent. Although funding costs for the banks are lower, banks are more affected by the drop in rates on interest-earning assets, so that their net interest margins decline.

- Interest rates do not have a linear impact on credit, nor do they have the same effect in all countries or on all banks. For example, banks with bigger deposit bases are relatively more affected as they cannot reduce the rates on their interest-bearing liabilities as much as they need to.

- Related to the non-linear effects mentioned above, monetary policy can even have the opposite of the intended effect whereby expectations and an ineffective lending channel result in lending volumes contracting rather than rising following a rate cut.

Trend in interest rates and bank margins in Spain

Having cut rates on several occasions since 2013, the ECB’s official rates have remained constant for the last three years. At its meeting in March 2016, the ECB’s Governing Council implemented its last rate cut across the board- the rates for the main refinancing operations and marginal lending facility falling by five basis points each- while it lowered the rate on its deposit facility by 10 basis points. Since then, rates have stood at 0.00% and 0.25% for main refinancing operations and the marginal lending facility, while the deposit facility rate now stands at -0.50%, following the latest 10 basis point cut in September 2019.

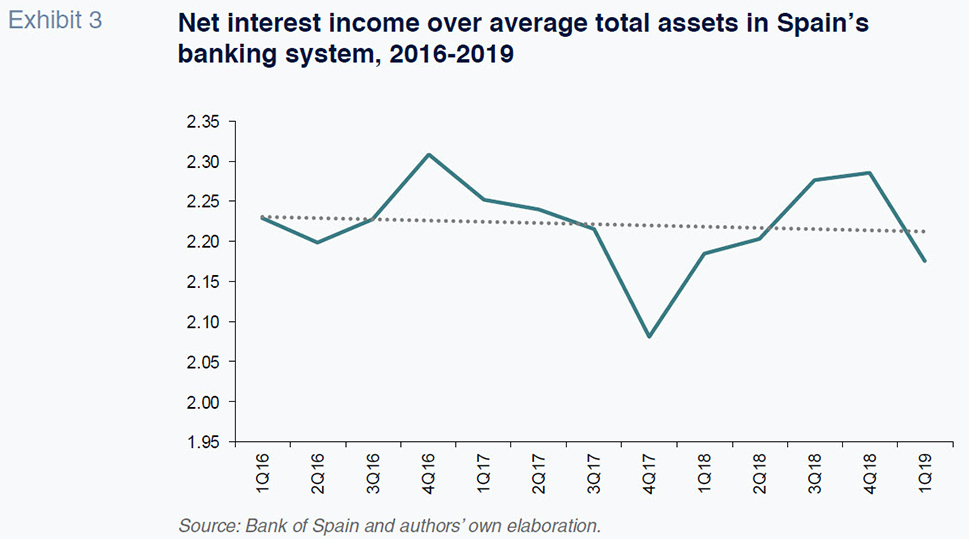

In parallel, bank margins in Spain have been relatively stagnant since the first quarter of 2016, as shown in Exhibit 3. Over the last three years, the interest margin over total assets has oscillated within a range of 2.08% and 2.31%, hitting a low of 2.08% in the last quarter of 2017. Although banks’ net interest margins recovered slightly in 2018, the results for the first quarter of 2019 show a setback. This has also been confirmed by the second-quarter numbers, pending the official aggregate figures for the sector as a whole. Although exhaustive econometric analysis is needed to determine the ultimate impact of the monetary environment (details to follow) on banks’ margins, the impact of official interest rates on bank margins is influenced by expectations to a considerable degree. Indeed, in the second half of 2018, expectations focused on rate hikes and that began to show (positively, albeit marginally) in the net interest margin. However, in 2019, with the sudden shift back to a more accommodative policy (new liquidity facilities and the prospect of ‘negative rates’), margins have contracted once more.

Regardless, there are factors and business strategies which are enabling the banks to mitigate the fallout from the ECB’s loose monetary policy. It is worth recalling that the Spanish banking sector has eliminated its surplus capacity and made a significant asset provisioning effort.

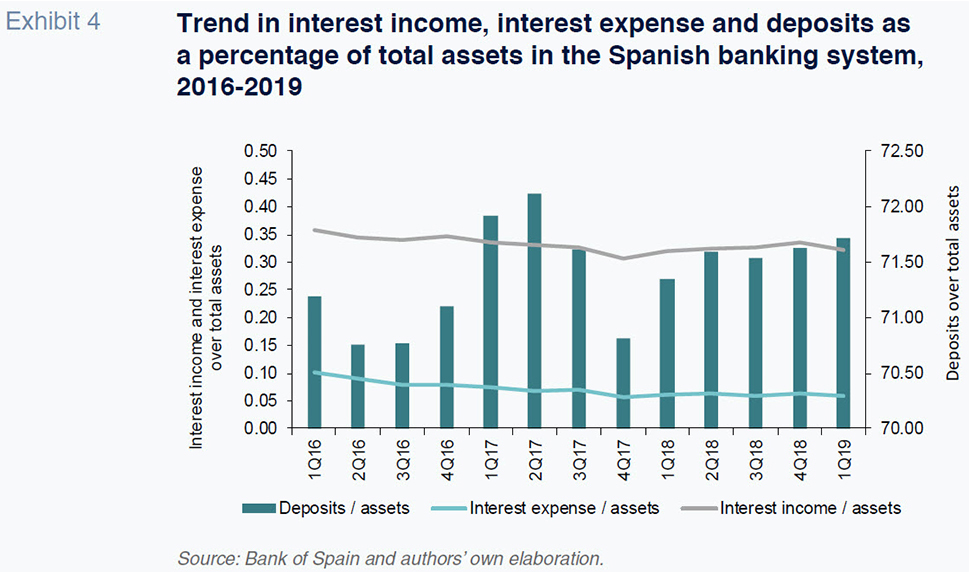

Exhibit 4 illustrates the trend in the components of the banks’ net interest margin, distinguishing between interest income and interest expense. Interest income, expressed as a percentage of assets, eased slightly from 0.36% in the first quarter of 2016 to 0.32% in the first quarter of 2019. The drop in interest income, partially attributable to low interest rates, has been offset by a contraction in interest expense, from 0.10% of assets to 0.06%. The simultaneous drop in interest income and interest expense means that the spread between the two has remained at around 0.26% (quarterly) from the first quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2019. However, this dynamic has its limits and is unlikely to continue indefinitely, particularly if rates enter negative territory, as rates on deposit remuneration will hardly follow suit. Moreover, the Spanish banks have replenished their deposit bases as a percentage of total assets in recent years. According to the academic reasoning outlined previously in this paper, that development leaves them more vulnerable to a negative rate environment.

Conclusions: Fallout from negative rates under debate

It is difficult to determine the extent to which negative interest rates for the ECB’s main financing operations could erode the banks’ earning. That said, most academic theories and empirical research suggest there is a causal link. Funcas is in the process of analysing the literature that addresses these concerns. This project also looks at some of the empirical evidence in Spain. The preliminary conclusions (in line with other studies) are:

- Monetary policy becomes less effective as rates fall closer to 0%. The bank lending channel loses functionality and ultra-low rates can have the opposite effects to those sought by policymakers (i.e., less credit), by generating negative expectations about the economy.

- Although lower interest rates can have the positive impact of reducing asset non-performance, the adverse effect on banks’ net interest margins is greater, so that the net effect on bank profitability is negative.

- The banks that fund themselves to a greater degree via deposits are more exposed to negative rates, which they are unable to fully pass on to their deposit holders. Longer term, the persistence of loose monetary policy has potentially negative implications for financial stability.

- The impact of negative interest rates on profitability is higher the lower a bank’s capital ratios.

- The empirical evidence suggests that to date, the ECB’s quantitative easing has had positive effects on lending volumes, though they have increased by less than was expected.

- Although in some cases, including that of Spain, net interest margins over total assets may look similar to those reported before the crisis, it is important to note a range of ‘composition’ effects which can ultimately have a negative impact on profitability: currently, together with the net interest margin, total credit and asset volumes are also waning and if the trend continues (or deteriorates in an adverse macroeconomic scenario), margins could contract further.

Lastly, beyond the ramifications for the banking sector, it is important to consider other adverse effects of negative interest rates. Those include price formation difficulties in the financial markets and exacerbation of debt accumulation. There is also the possibility of cash hoarding, insofar as those holdings are not penalised by negative rates. Lastly, we must not forget the nexus between negative interest rates and exchange rates and the potential implications in the event of trade tensions, as is currently the case.

Notes

Negative remuneration on accounts and/or negative mortgage rates have legal restrictions in some jurisdictions. In Spain, for example, the new real estate credit law expressly states, in relation to operations at variable interest (Article 21.4), that “the remuneration interest in such operations may not be negative”.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. CUNEF, Bangor University and Funcas

Pedro Cuadros Solas. CUNEF and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas