The World Bank’s Doing Business in Spain 2015 report: Analysis and main conclusions

The World Bank’s recent report Doing Business in Spain 2015 reveals significant differences in regional regulations affecting business activity. While there may be some limitations to estimating the impact of the reports’ findings on economic variables, the study still highlights the need to further improve business regulation across all of Spain´s regions.

Abstract: This article presents the key results of the Doing Business in Spain 2015 report concerning the business regulations affecting SMEs and analyses them in relation to variables representative of regional economic activity in Spain. The key findings of the report reveal significant differences across the regions in terms of regulations affecting business activity. On aggregate, the best performing region is La Rioja, followed by Madrid, while the worst-and second-worst ranked regions are Galicia and Aragon, respectively. Although it is important to point out that some of the regions towards the bottom of the overall ranking still fare relatively well on certain indicators. Analysis of the reports’ results, however, suggests that several of the scores achieved are not as statistically significant as anticipated as regards their impact on key economic variables. In any event, the study’s limitations do not detract from the importance of making further progress on reforms aimed at improving the regulatory climate for doing business in Spain’s regions as a means to facilitate business creation and development.

Regulations that affect business activity are one of the few remaining economic-policy areas over which the eurozone’s governments still have discretionary power. Monetary policy falls exclusively within the European Central Bank’s remit and fiscal policy has ceased to be an area over which governments have absolute decision-making power on account of the limits and constraints imposed by the eurozone’s economic policy-makers. It is natural therefore for governments, at their various levels, to focus their attention on regulating businesses’ activities.

In addition, in the specific case of Spain, as recently noted in SEFO (2016), the gap between the richest and poorest regions is set to widen in 2016. The widening of this gap is attributable, in part, to the fact that the best-positioned regions have economic structures dominated by specific sectors and industries that are more oriented towards servicing foreign demand (automotive, food industry and tourism, for example).

The concern prompted by this regional divergence in certain social, economic and political spheres can inevitably lead to questions regarding regional regulations and, in particular, their heterogeneity. To what extent are regulatory differences in Spain responsible for the fact that its regions face different economic realities and outlooks? Is Spain the victim of “regulatory races”

[1] that are harming the general interest? Do some regional governments introduce disproportionate regulatory barriers in an attempt to protect their local markets and companies?

It is possible that questions such as these prompted the Spanish government to ask the World Bank to compile the Doing Business report on regional business regulations in Spain published in 2015 (World Bank, 2015; hereinafter, DBS2015). The goal of this paper is to outline the key results of that report and analyse them in relation to variables deemed representative of regional economic activity in Spain. This paper does not purport to provide answers to the questions raised above but does express certain opinions aimed at helping the reader assess to what extent the DBS2015 can do so.

Background and the Doing Business report’s methodology

According to the report itself, DBS2015 “analyses business regulations from the point of view of small and medium-size enterprises. The assumption is that both the regulations and business climate have a significant impact on a country’s economic activity.

If laws and regulations are clear, accessible and transparent ‒ and enforceable in a court of law ‒ entrepreneurs can devote more time to productive activities. They will also feel more confident doing business with people they do not know, expanding their client and supplier networks and helping their businesses grow.”

Using the methodology customarily deployed in this kind of report at the state level, business regulations are studied by choosing some of the key stages in the life of a business and asking a series of local experts their opinion on the aspects studied. In the World Bank’s regular reports on national regulations, 10 areas are systematically studied,

[2] while others are analysed on an occasional basis.

[3] The DBS2015 report provides information on just four of these: starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity and registering property. These four areas of interaction with regulatory processes were selected because they cover areas of regional or local jurisdiction or practice.

The report studies business regulations in each ‘autonomous community’, using as its proxy the regulations applied in each region’s most populated city. The scope of the study therefore encompasses the 17 regional governments (represented by 17 cities) and the two ‘autonomous cities’ (Ceuta and Melilla). For each indicator, the results correspond to the concept known in the Doing Business studies as the ‘distance to the frontier’ (DTF). A region’s distance to the frontier is indicated on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 represents the lowest performance and 100 the best global practice, or the ‘frontier’, in each area of analysis (Sánchez-Bella, 2015 and Llobet, 2015).

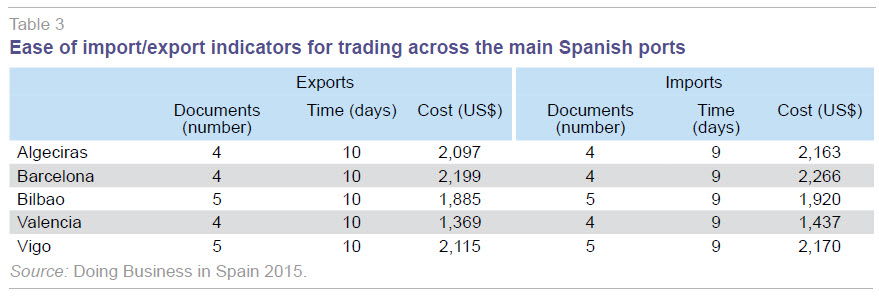

In addition, in the case of the ports of Algeciras, Barcelona, Bilbao, Valencia and Vigo, the report studies the time, cost and number of documents needed to import or export across borders.

The DBS2015 report states that it based its findings on the individual questionnaires obtained from over 350 local experts from the private sector (including notaries, property registrars, experts in government dealings, lawyers, architects, engineers, professional associations, customs agents, freight forwarders, logistics companies, port operators, utility providers, construction companies, consultants and independent professionals) and that more than 400 public officials from all government levels also participated in the data collection process.

The study was requested by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain and financed by ICEX Spain Trade and Investment with funds from the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union.

Doing Business in Spain 2015: Main findings

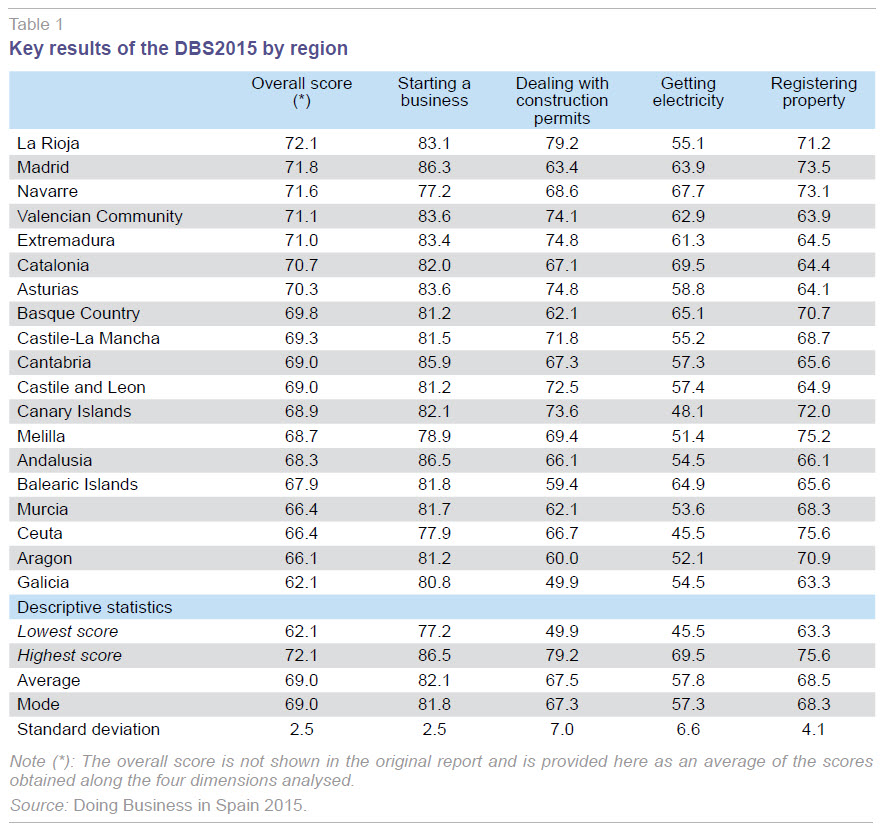

The key findings of the DBS2015 report are presented in Table 1, in which the regions are presented in order from the highest- to the lowest-scoring regions (overall scores).

As the table shows, using the aggregate score for ease of doing business, the best-performing region is La Rioja, followed by the Community of Madrid, while the worst- and second-worst ranked regions are Galicia and Aragon, respectively. As illustrated by the descriptive statistics provided in Table 1, there are significant differences in regulatory efficiency, measured using standard deviations, for each of the four indicators, the differences being very pronounced in the cases of dealing with construction permits and getting electricity.

In addition, as noted by Sánchez-Bella (2015), with the exception of dealing with construction permits, all of the regions fall below the European Union average and none ranks in the top quartile in terms of its overall score. And, as noted by Llobet (2015), some of the regions towards the bottom of the overall ranking fare relatively well on certain indicators. For example, Ceuta, which ranks #15 (out of 19) on the overall ranking but number one on property registration. Similarly, Andalusia, ranked #14 overall, is the best-performing region for starting a business.

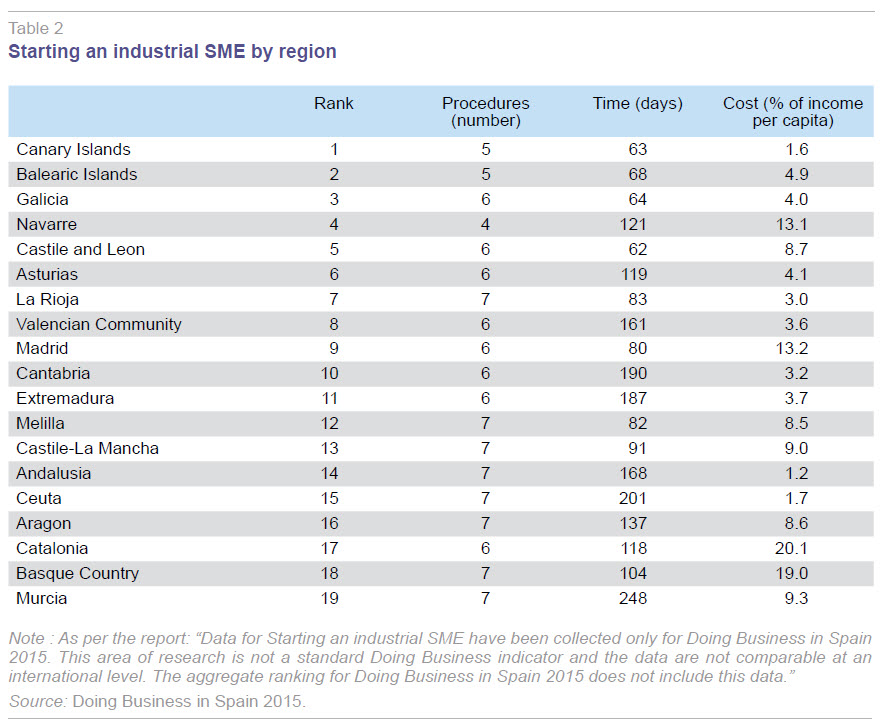

The report also provides indicators regarding the ease of starting an industrial SME, which are presented in Table 2.

The study is rounded out with a comparison of the different requirements for importing or exporting goods through Spain’s five main ports; these are shown in Table 3.

Analysis of the results

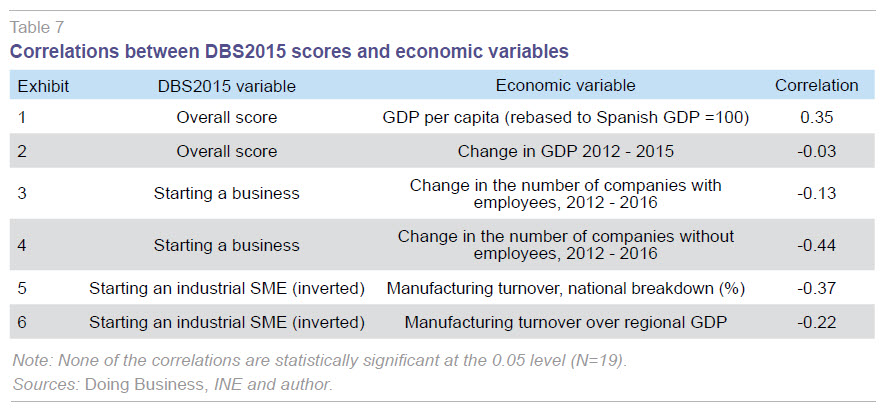

This section analyses the relationship (correlation) between some of the scores provided in the Doing Business in Spain 2015 (DBS2015) report and certain regional economic indicators. By way of summary, Table 7 reports the correlations depicted in Exhibits 1 - 6.

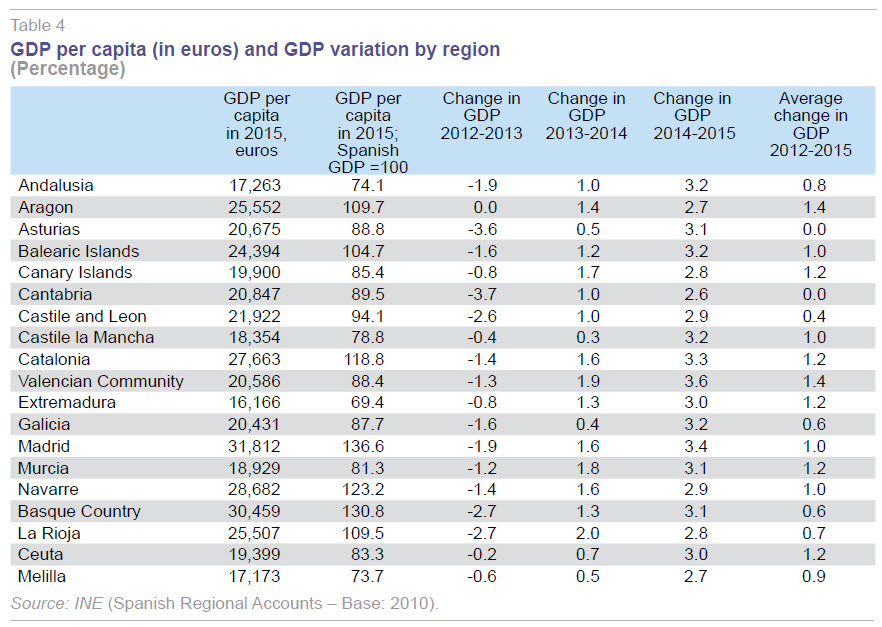

Firstly, the overall DBS2015 score is correlated with two measures of regional economic development. Table 4 presents GDP per capita per region in

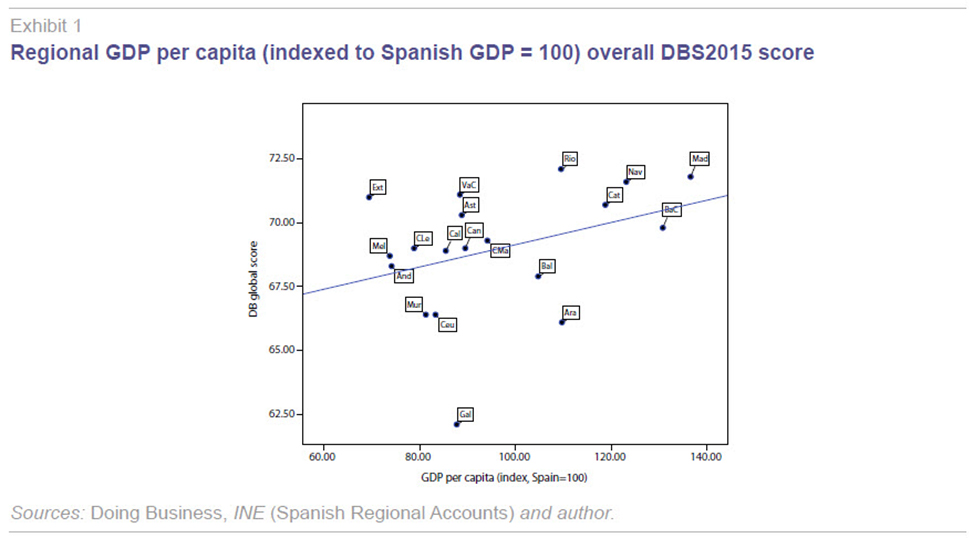

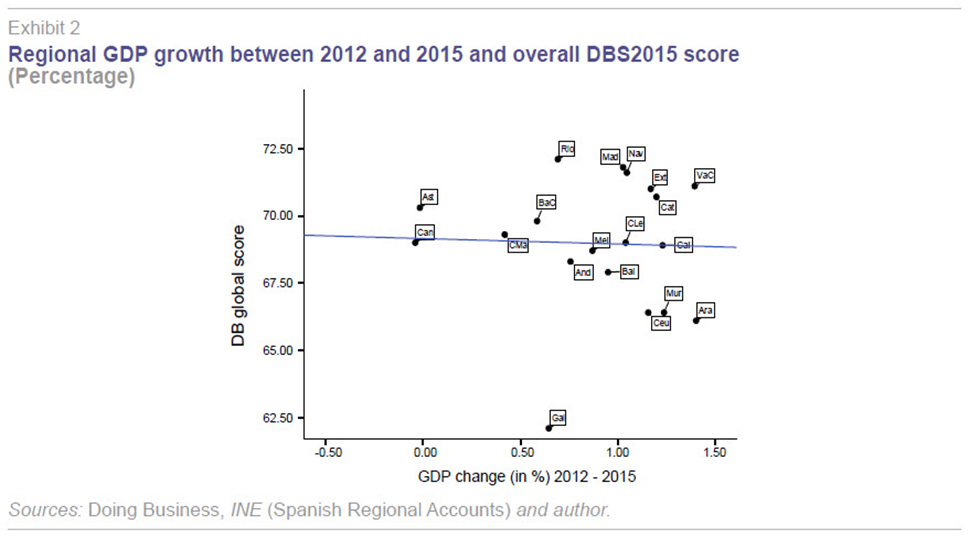

2015 in absolute terms (in euros) and as an index (relative to overall Spanish GDP, rebased to 100). It also provides the annual regional GDP growth figures for 2013, 2014 and 2015 and the average of the three readings. Exhibit 1 shows the correlation between each region’s overall DBS2015 score (column one in Table 1) and its GDP per capita relative to the national average (column two in Table 4). Exhibit 2 shows the correlation between the DBS2015 scores and average regional GDP growth between 2012 and 2015 (column six in Table 4).

As shown in Exhibit 1, there is a slight positive correlation (0.35) between the overall DBS2015 score and regional GDP per capita but there is no clear correlation between the overall score and average regional GDP growth (-0.03). The correlations are not statistically significant in either instance (Table 7).

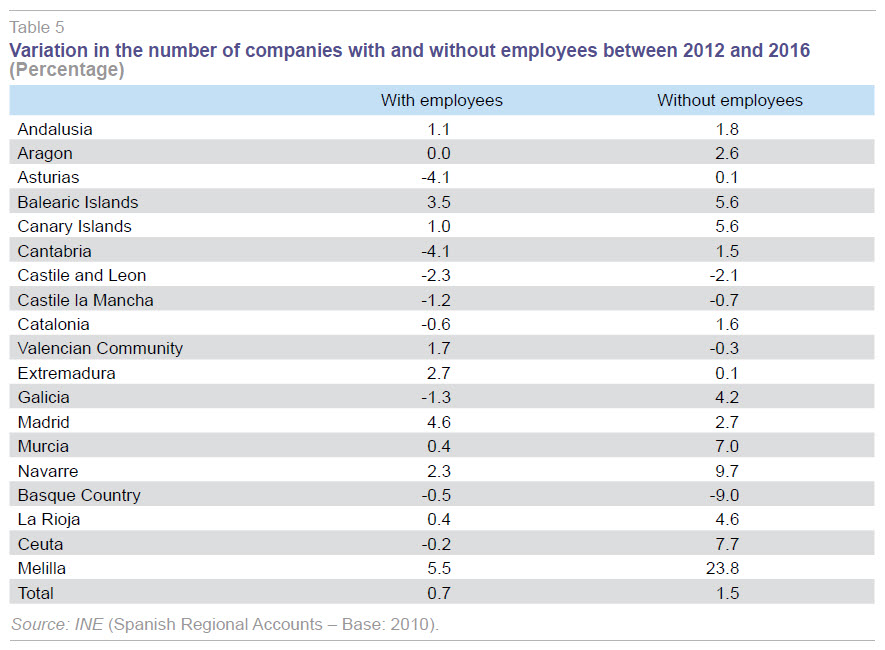

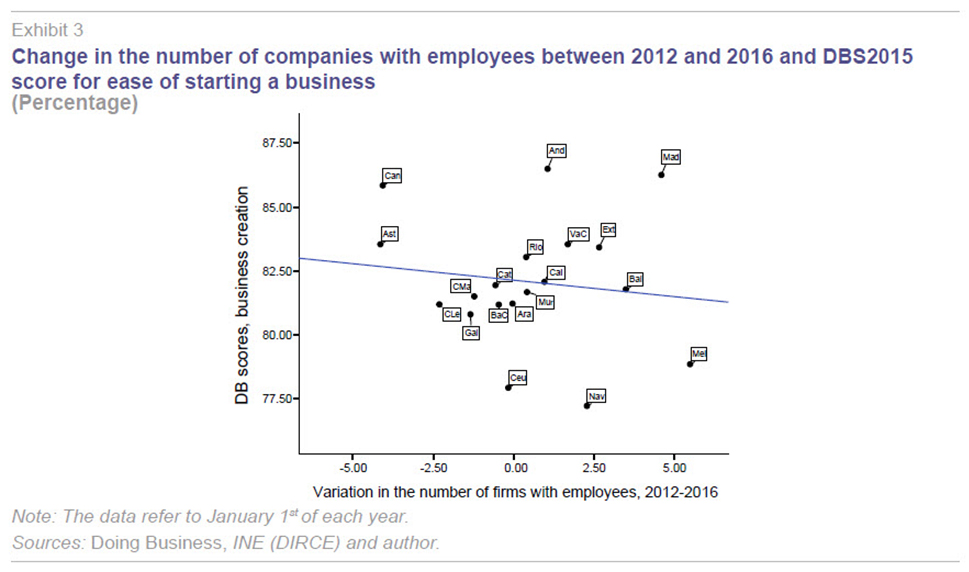

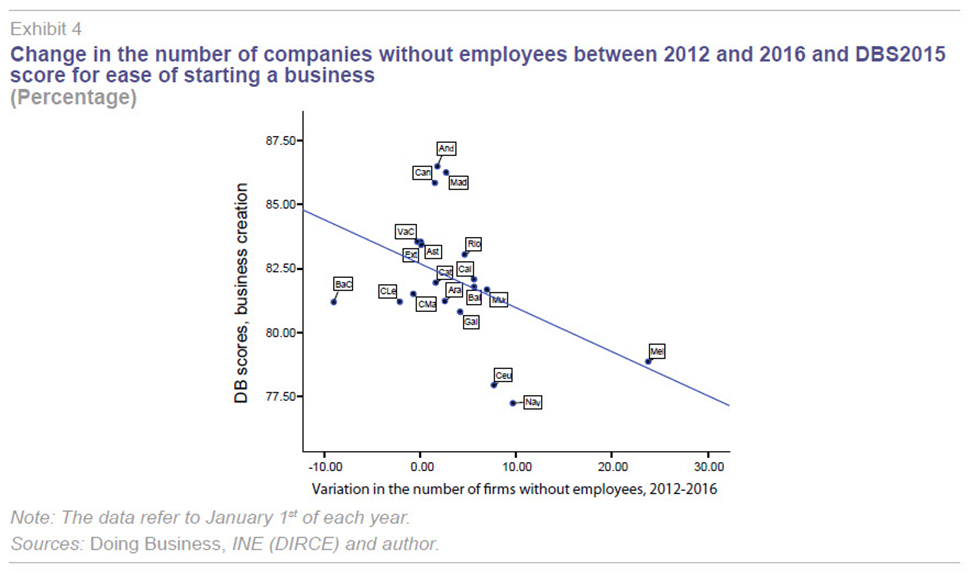

Secondly, an attempt was made to correlate the ease of setting up a business DBS2015 scores (column two of Table 1) with two measures of business dynamism at the regional level. Table 5 shows the percentage change in the number of businesses between January 1

st, 2012, and January 1

st, 2016, in each region, based on the national statistics bureau’s central companies database (INE-DIRCE), distinguishing between companies (taking any legal form) with employees and businesses without employees (

i.e., self-employed professionals). The correlations between the DBS2015 scores and these two variables are shown in Exhibits 3 and 4, respectively.

In both instances the correlations are negative and not significant, yielding a correlation of -0.13 with respect to the change in the number of businesses with employees and of -0.44 in the case of self-employed professionals (Table 7).

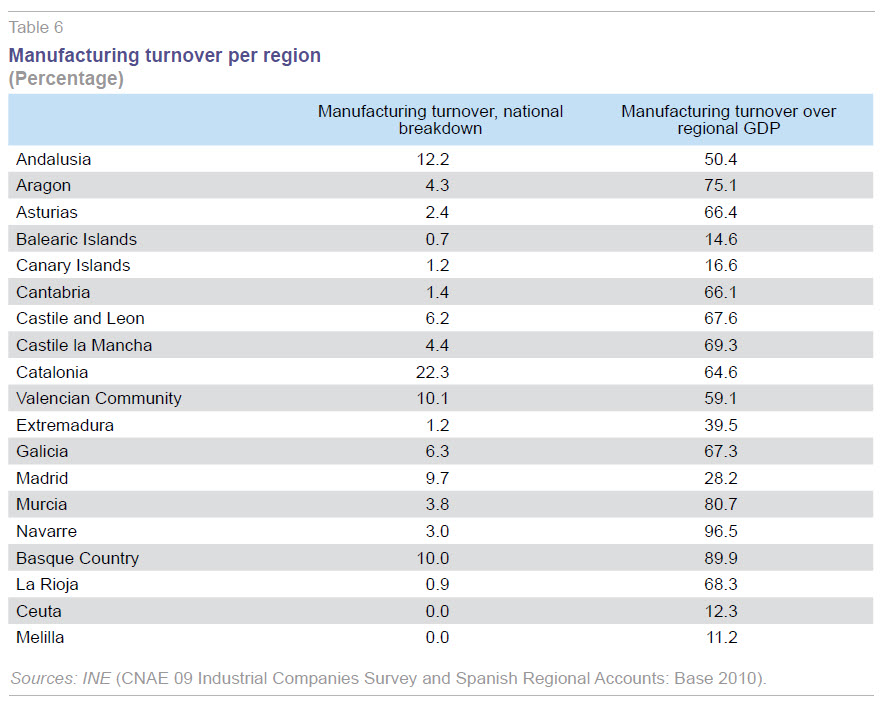

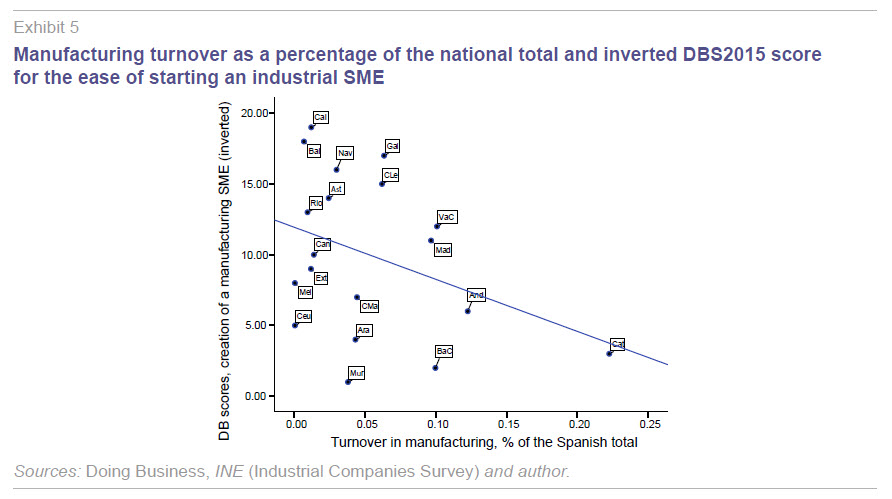

Third and last, the correlation between the DBS2015 scores measuring the ease of setting up an industrial SME and two indicators capturing the importance of manufacturing is analysed. Column one of Table 6 provides the regional breakdown of total national manufacturing turnover using INE survey data. This measure is affected by the size of each region (the smaller regions command, irrespective of the efficiency and competitiveness of their industrial sectors, a relatively lower share of overall manufacturing turnover), which means that any potential correlation with the DBS2015 scores should be analysed more in qualitative rather than in quantitative terms in this instance.

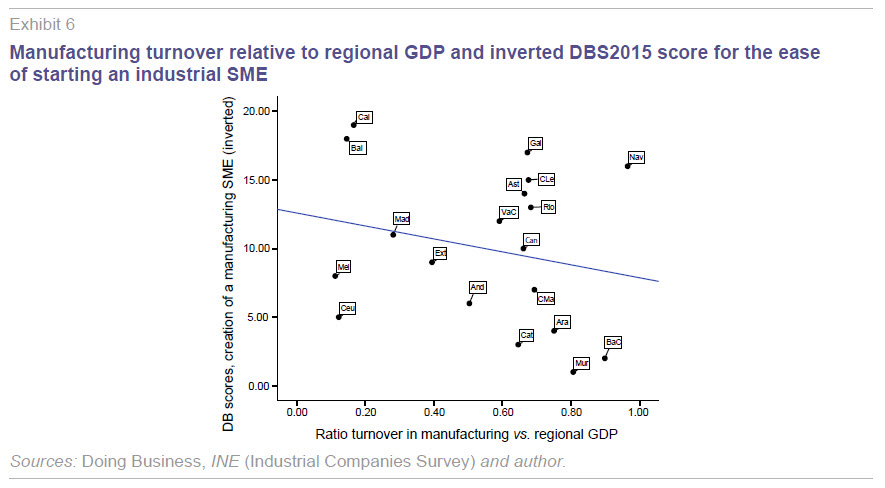

Column two in Table 6 shows manufacturing turnover per region as a percentage of regional GDP. Note that this indicator cannot be interpreted as a direct measure of the relative presence or importance of industry in a given territory as variables are different in nature (turnover represents company revenue while regional GDP calculates the region’s aggregate value added). Nevertheless, this second measure eliminates the regional size skew.

The correlations between the DBS2015 scores for ease of starting an industrial SME and these two measures of the relative importance of the manufacturing industry at the regional level are provided in Exhibits 5 and 6, respectively. For ease of interpretation, in these exhibits and in the correlation coefficient calculations, the DBS2015 scores are inverted,

i.e., the highest score corresponds to a 19 and the lowest to a 1.

As illustrated by both exhibits, the DBS2015 scores are negatively correlated to the variables used as proxies for the importance of the manufacturing industry in each region (with coefficients of -0.37 in respect of the national breakdown of manufacturing turnover and -0.22 in the case of turnover relative to regional GDP; moreover, the correlation is not statistically significant in either instance ‒ Table 7).

Debate and conclusions

The above analysis suggests that several of the Doing Business report’s scores on regulatory efficiency in Spain (DBS2015) are not correlated, within the realm of statistical significance, with the key economic variables on which the areas of regulatory interaction should have an impact. Moreover, in several instances, the scores and the variables are inversely correlated to what one might expect (Table 7).

In short, in statistical terms, the DBS2015 scores cannot be deemed reliable predictors of, among other variables, regional GDP per capita in 2015, average regional GDP growth between 2012 and 2016, the change in the number of companies or the relative importance of the manufacturing industry in each region.

The reasons that these correlations do not hold may be multiple and mutually compatible.

- The analysis does not factor in regional considerations of a historic nature or related to their economic structures. These factors, such as market size (the scale of the customer and supplier network), industrial trajectory or the logistical positioning of each region, may belie a relative greater degree of economic development in a given region irrespective of the DBS2015 regulatory efficiency scores. Spanish companies are not set up in a given region or sector depending solely on theoretically more propitious regional regulations; rather these decisions take into account the pre-existing economic landscape. Company size is another factor omitted from this analysis and one that has a significant impact on an economy’s productivity (Xifré, 2016).

- An alternative explanation for the results is that the more business activity there is in a given region, the more exhaustive or complex its regulations may become over time (implying a greater burden for its companies). Faced with a proliferation of businesses operating in a given sector and territory, the authorities may consider it necessary to tighten up the regulations governing such activities. In this instance, “more regulations” should not be viewed as a brake on economic activity but rather the public sector’s reaction to a dynamic business situation that warrants clarifying and detailing the rules under which the companies operate. This interpretation may be useful in putting the adverse consequences some have attributed to so-called “regulatory races” into perspective. As shown in a recent paper by Carruthers and Lamoreaux (2016), the conditions for regulatory races to occur hold only in rare circumstances; rather, the much more common outcome tends to be political interference in an attempt to favour specific interest, placing them before the general interest.

- Lastly, it is worth urging a note of caution regarding the methodology used in the Doing Business reports, in line with the independent evaluation carried out on these types of studies by the institution itself (World Bank, 2008). The independent report compiled by the World Bank about its own methodology concludes that the “the indicators [...] cannot by themselves capture other key dimensions of a country’s business climate [and] the benefits of regulation”. Despite the fact that subsequent to this report, the World Bank has adapted some of the Doing Business report methodology, some of the critiques of substance put forward in the independent report remain valid. Against this backdrop, these scores can be considered partial or incomplete for the purpose of assessing the regulatory efficiency of a given territory. For this reason, it is not too surprising that the scores are not significantly correlated to certain key regional Spanish economic variables.

These report limitations do not, however, in anyway detract from the importance of the questions that prompted the study in the first place. Is there scope for the various regions to improve their business regulations in order to facilitate business creation and development? Very probably, the answer is yes and there are numerous issues that can still be tackled and extensive international case studies for guiding on this matter (Xifré, 2015).

In fact, to tackle the regulatory issue in a satisfactory manner, it would appear more promising, from the standpoint of public spending efficiency, to make progress on the line of initiative embarked on by the CORA (acronym in Spanish for the Commission for Public Administration Reform) in terms of reviewing existing public legislation to prevent overlap and enhance regulations. If further inroads are to be made in this direction it is worth cautioning, however, that progress will be limited by the ability displayed at the various levels of government to overcome the confrontational dynamic and move towards scenarios of genuine inter-governmental cooperation to the benefit of businesses and citizens.

Notes

Processes in which, theoretically, different jurisdictions compete with each other to relax their business regulations in an attempt to attract companies to their regions.

The areas studied generally in reports that are national in scope are: starting a business; dealing with construction permits; getting electricity; registering property; getting credit; protecting minority investors; paying taxes; trading across borders; enforcing contracts; and, resolving insolvency.

Namely, labour market regulations and selling to the government.

References

CARRUTHERTS, B. G., and N. R. LAMOREAUX (2016), “Regulatory Races: The Effects of Jurisdictional Competition on Regulatory Standards,”

Journal of Economic Literature, 54(1): 52-97.

LLOBET, G. (2015), “Doing Business in Spain”,

Nada es Gratis, a blog post available at

http://nadaesgratis.es/gerard-llobet/visual-y-basico-haciendo-negocios-en-espanaSÁNCHEZ-BELLA, P. (2015),

Trabas regulatorias y PYME en España [Regulatory red tape and SMEs in Spain], Politikon, a blog post available at

http://politikon.es/2015/12/03/trabas-regulatorias-y-pymes-en-espana/SEFO (2016),

Regional Economic Forecasts, October 2016. Available at

http://www.funcas.es/Indicadores/Indicadores_img.aspx?Id=4&file=0WORLD BANK (2008),

Doing Business: An independent Evaluation. Taking the Measure of the World Bank-IFC Doing Business Indicators.

— (2015).

Doing Business in Spain 2015, available at

http://espanol.doingbusiness.org/reports/subnational-reports/spainXIFRÉ, R. (2015). Recent reforms in Spain’s business climate: Assessment and pending issues,

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 245: 63-72.

— (2016). Spain’s business landscape: Structure, recent developments and remaining challenges,

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 252, 21-29.

Ramon Xifré. Professor at ESCI-Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Policy Research Follow at PPSRC-IESE Business School