Spain’s regional economic outlook: On track for recovery amidst rising inequality

In line with the Spanish economy’s overall performance, regional governments remain broadly on track to recovery. Nevertheless, growth across the regions is becoming increasingly uneven since the crisis, making it necessary for Spain’s future reform agenda to launch specific measures to tackle regional imbalances.

Abstract: The Spanish economy has experienced a vigorous recovery. Last year, GDP grew by 3.2%, in sharp contrast to the weak performance registered in the aftermath of the crisis. Latest available indicators suggest momentum has been maintained so far this year and growth for 2016 looks set to come in at 3.1%, close to double the European average, albeit slowing somewhat to 2.3% in 2017. At the regional level, activity indicators for the first half of 2016 confirm the recovery across all regions, although at distinct speeds. Fiscal consolidation has also broadly improved in the first eight months of 2016, stemming from increased revenues and lower spending. Despite the favourable regional outlook, however, disparities across the regions since the crisis are intensifying, with implications for productivity, ageing population, and unemployment levels. Public policy should take into consideration measures to reduce regional inequalities, such as well-designed investment and redistribution policies, as well as to correct deficiencies in some regions’ education levels.

Recent developments

All regions are now on the path to recovery, albeit with some performing better than others. Catalonia, Valencia and Madrid were the fastest growing regions in 2015, while Aragon, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile-Leon, Navarre and La Rioja lagged behind. Andalusia, Asturias, the Balearic Islands, Castile-La Mancha, Extremadura, Galicia, Murcia and the Basque Country all grew in line with the national average.

According to Funcas’ Synthetic Activity Indicators, the regional recovery held steady during the first half of the year. Valencia and Madrid look to have registered especially robust growth. But the indicators are less positive for Asturias, Cantabria, Castile-Leon and La Rioja, all of which may have grown more slowly than the economy as a whole.

Industry, construction and market services (including tourism) were the sectors driving the recovery in nearly all regions, with agriculture generally rather weak.

Services grew fastest in the first half of the year, especially in regions with a significant tourism component to their GDP, such as Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Murcia and – to a lesser degree – the Canary Islands. Galicia also saw very positive growth in tourism.

Industrial activity was strongest in Castile-Leon, followed by Murcia. Meanwhile the Basque Country led the way in construction, followed to a lesser degree by Catalonia and Navarre. Overall, residential construction activity showed signs of picking up – particularly in Madrid, Catalonia and the Basque Country – but public works contracted, most notably in Aragon.

Regional labour market developments mirrored economic growth with unemployment falling in almost all regions. The only exception was Asturias, where the unemployment rate in the first three quarters remained broadly unchanged relative to the same period last year. There was also barely any decline in unemployment in Navarre.

According to Labour Force Survey (LFS) data, Murcia, the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands led the way in terms of job creation during the first half of the year. However, employment increased least rapidly in La Rioja, Madrid and Cantabria, and even fell in Navarre. The latter conflicts – as is sometimes the case – with social security registrations data to September. These reported an increase in employment in Navarre in line with the national average and a slight outperformance in the case of Madrid.

Progress in terms of the public deficit has been more varied. The regions’ overall deficit barely changed last year, remaining at 1.7% of GDP. However, the deficit declined by 0.7 percentage points during the first eight months of 2016. Andalusia, the Canary Islands and Valencia registered the largest consolidation. Only Cantabria reported an increase in its deficit. Regional deficit consolidation has stemmed from both an increase in revenues, largely due to the favourable adjustment relating to the 2014 financing round, and lower spending.

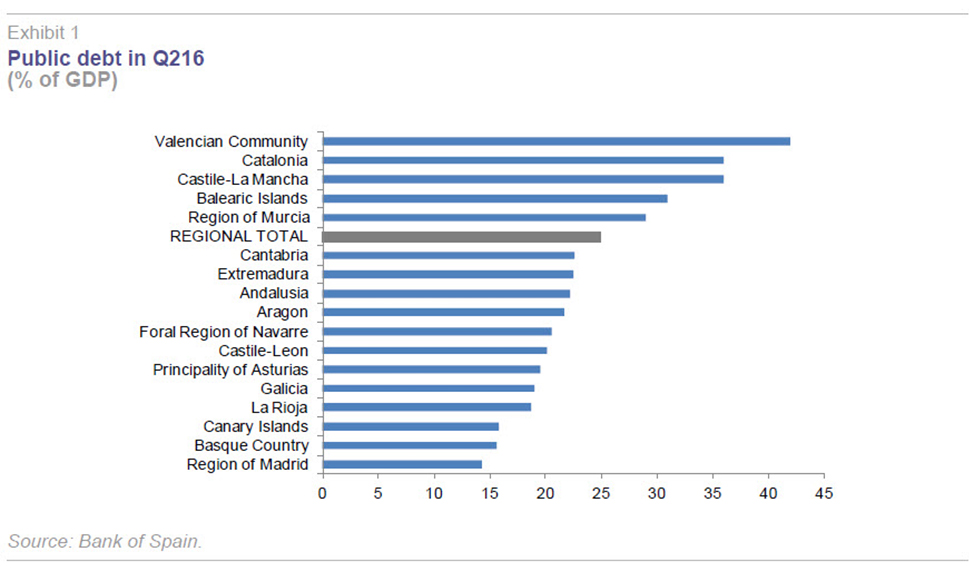

Overall, regional indebtedness rose to 24.9% of GDP (Exhibit 1) in the second quarter, representing a 1.2 percentage point increase relative to the year before. The most indebted regions are Valencia, Catalonia and Castile-La Mancha, while Madrid, the Basque Country and the Canary Islands have the lowest levels of debt. Debt rose most sharply in Catalonia and Extremadura during the first six months of the year, while the Canary Islands was the best performer, managing to keep debt levels unchanged in contrast to all other regions. Nearly a half of all regional debt is owed to the State. Murcia and Valencia owe 71% of their total debt to the state, compared to Madrid which has just 6.6% of its debt with the state.

Forecasts for 2016 and 2017

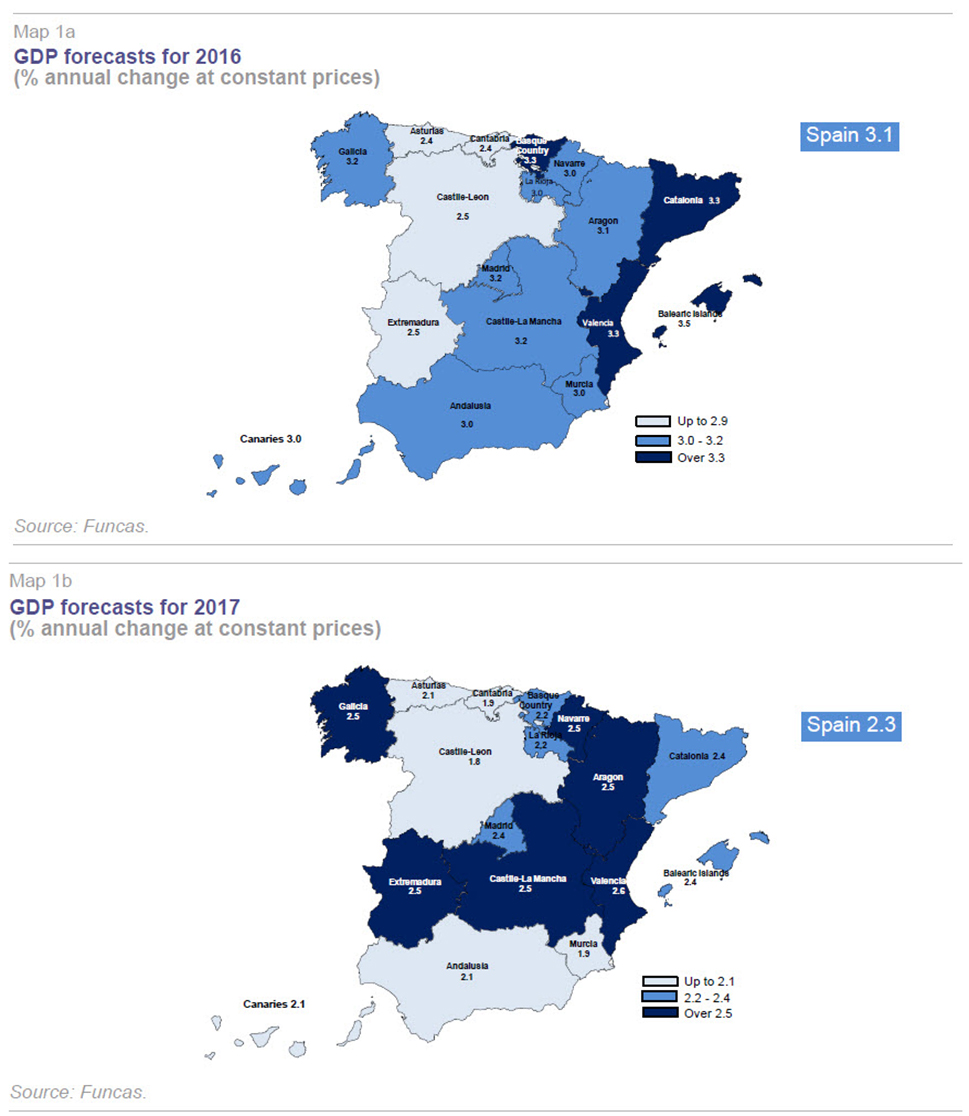

National economic growth is set to ease, with some indicators of demand, production and employment already pointing to deceleration. Overall, the Spanish economy could grow by 3.1% in 2016 and 2.3% in 2017. The Balearic Islands, Catalonia, Castile-La Mancha, Valencia, Galicia, Madrid, the Basque Country and to a lesser extent Aragon and Navarre should see above average growth during the forecast period (Maps 1a and 1b).

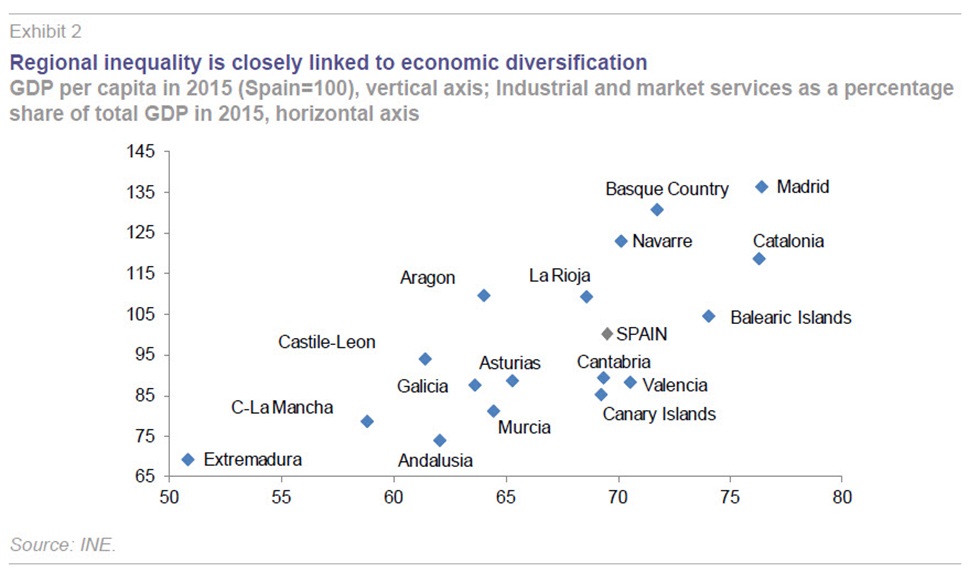

These regions are either especially benefiting from tourism (Mediterranean regions) or have successfully diversified their productive structure (Ebro axis, Madrid and neighbouring regions, as well as urban areas of Galicia). Indeed, diversification is a key factor explaining the persistent disparities across regions (Exhibit 2).

By contrast, Asturias, Cantabria, Castile-Leon and Extremadura look set to be the least dynamic. These regions are struggling to take advantage of the upswing in exports. This is partly due to location with some being relatively regional, or having an industrial structure particularly affected by the crisis. Moreover, these regions tend to suffer from population loss.

Finally, Andalusia, the Canary Islands and Murcia are likely to be in the middle, with slightly below national average growth rates forecast for 2016 and 2017.

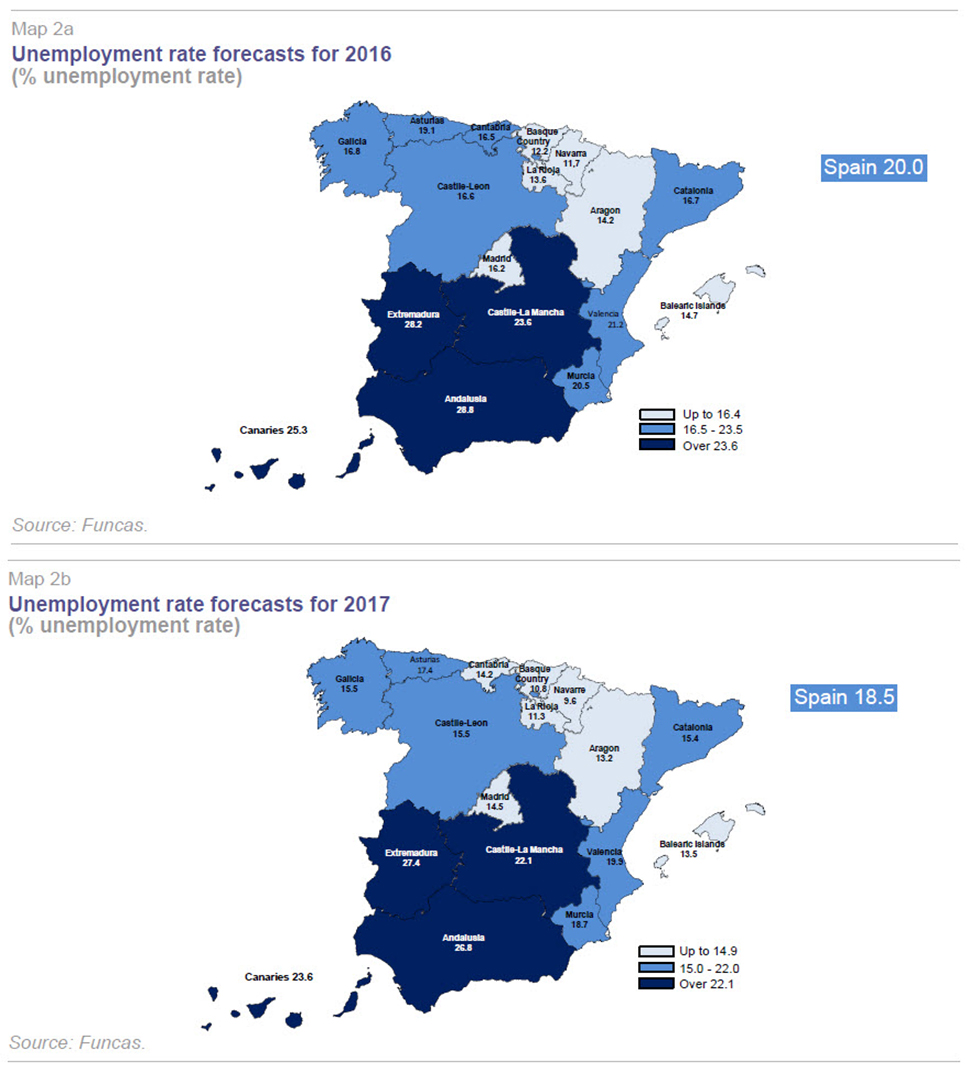

LFS employment growth should be strongest over 2016-17 in the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands and Murcia. Extremadura, Madrid and Castile-Leon will likely register the weakest rates of job creation. Navarre is set to be the only region with an average annual unemployment rate below 10% in 2017; whereas unemployment may well remain over 20% in Andalusia, the Canary Islands, Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura. Broadly speaking, the decline in the active population means unemployment will fall more rapidly than corresponding increases in employment, except in Valencia and the Balearic Islands (Maps 2a and 2b).

Regional disparities since the crisis

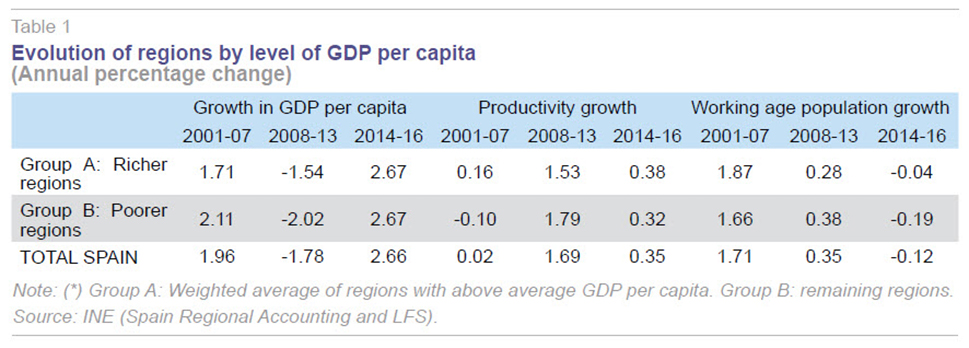

The disparities between regions are intensifying (Table 1), especially when viewed from the perspective of an entire cycle - expansion (2000-2007), recession (2008-2013) and recovery (2014 onwards).

During the upswing, average annual growth in GDP per capita of the least well off regions reached 2.1% p.a., 0.4 percentage points above more prosperous regions. However, this convergence process reversed during the core crisis years. As such, from 2008-2013, GDP per capita of deprived regions fell by half a percentage point more than more prosperous regions. And this gap has been sustained during the current recovery.

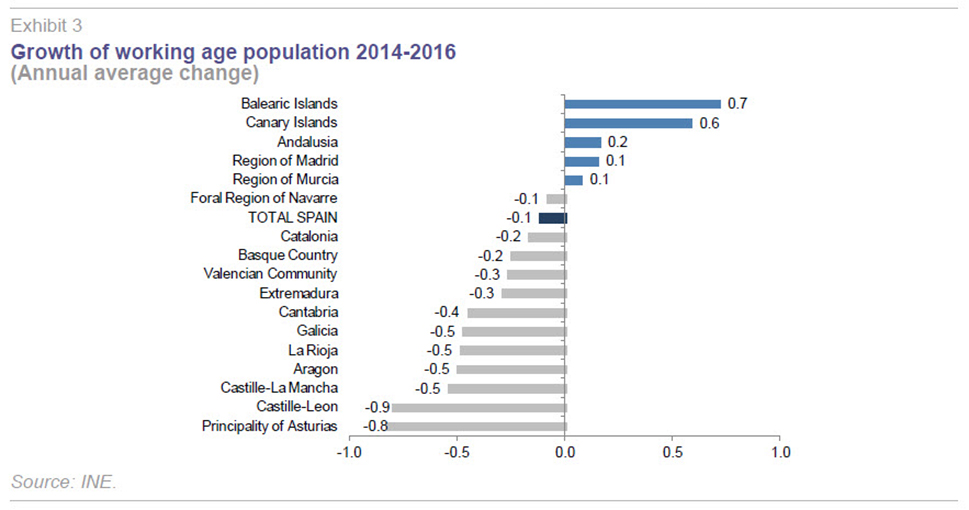

Furthermore, regions with lower income per capita are lagging behind in terms of productivity and are losing population (Exhibit 3). Since 2014 productivity growth in these regions has dropped from above average growth rates to close to the national average. Meanwhile, their working age population has shrunk in contrast to more prosperous regions where the population has held steady.

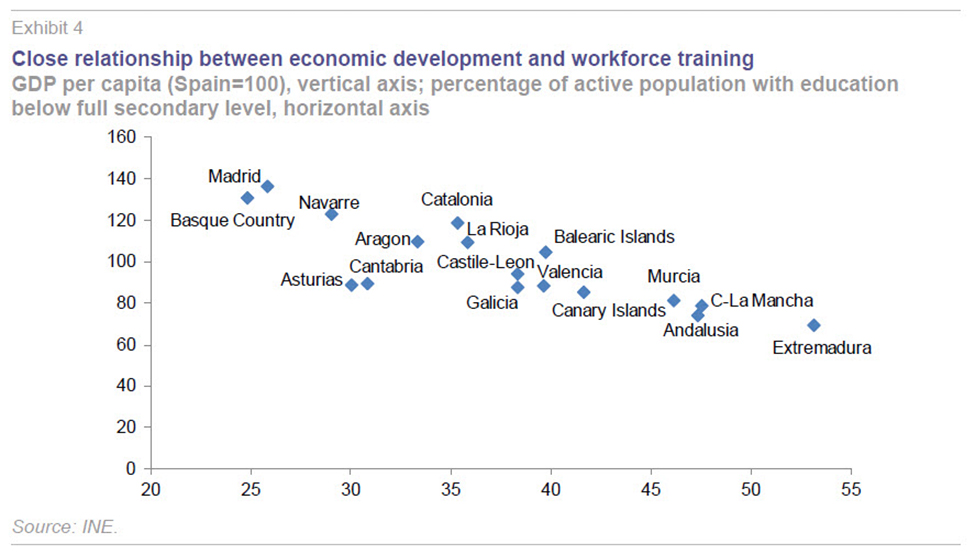

Furthermore, there is a very strong relationship between GDP per capita and the education levels of the active population (Exhibit 4). The poorest regions – Andalusia, Extremadura and Castile-La Mancha – are also those which have the largest percentage of their active population with lower than full secondary level education. The richest regions – Madrid, Basque Country and Navarre – have better educated active populations. The significant deficiencies in education levels are probably another one of the factors behind poorer regions’ lower productivity levels, in addition to their less diversified productive structures.

Likewise, regional differences in terms of employment have also become more notable. Prior to the start of the crisis, in 2007, the highest unemployment rate was 13% (Extremadura) and the lowest was 4.7% (Navarre) – a difference of 8.3 percentage points. Meanwhile in 2016, five regions registered unemployment rates in excess of 25% (Andalusia, the Canary Islands, Extremadura, Ceuta y Melilla), with another five below 15% (Aragon, the Balearic Islands, Navarre, the Basque Country and La Rioja).

Spain is not alone in facing increasing spatial inequality. According to the OECD, regional divergences have widened during the last two decades in the majority of developed economies. Productivity is rising more rapidly in more prosperous areas, while deprived regions are struggling to make the same progress. Nonetheless, there are exceptions to this pattern, indicating that there is still potential for public policy to play a role in addressing these disparities.

Implications for public policy

Mitigating regional disparities is one of the most complex tasks facing public policy. Economic growth is helpful insofar as it provides resources for measures to support investment and employment, but it is not sufficient. This is underlined by the significant increase in inequality that took place in Spain and other European countries since the crisis and into the recovery period. Moreover, more recently, growth has tended to focus on regions already showing high productivity, leaving poorer regions struggling to keep up.

A strategy is required to address these imbalances without harming the progress of more dynamic regions. International experience suggests two types of action could be especially pertinent. Firstly, nuanced investment policies that promote development in less productive regions – by strengthening their business fabric – while supporting infrastructure in more dynamic regions to avoid possible bottlenecks. Investment in large scale infrastructure in poor regions usually has only a minor effect on productivity differentials.

Secondly, a properly designed redistribution policy is needed to support individuals on lower incomes, improve education and encourage labour market participation.

These results could inspire future reforms in Spain. In this regard, regional financing could make a greater distinction between income redistribution and policies aimed at promoting economic development in different regions.

Improving the design of the different mechanisms for equality and tax responsibility would also be a welcome step forward. Redistribution should involve a substantial overhaul of active labour market policies, which would require new equality criteria. The focus for economic development policy should be on stimulating investment projects that meet the demands of each individual region. Corresponding tax responsibilities could be helpful in this regard, as has shown to be the case in Federal states such as Germany or Canada.

Finally, urgent and determined action is needed in education. It is vital that policy be put in place to correct the significant deficiencies in education levels of the population in less developed regions, given the role an educated workforce plays in productivity, salary levels and the economic activities that can be developed within a region.

Overall, the increasing level of regional inequality poses a significant challenge for national cohesion. Economic growth by itself is insufficient. meaning specific action will be required to boost investment potential and employability in the most deprived regions, at the same time as maintaining dynamism in the rest of the country.

References

BARTOLINI, D.; STOSSBERG, S., and H. BLÖCHLIGER (2016), “Fiscal decentralisation and regional disparities,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, nº 1330, Paris.

CRISCUOLO, C. (2015), “Productivity is soaring at top firms and sluggish everywhere else,” Harvard Business Review, August (https://hbr.org/2015/08/productivity-is-soaring-at-top-firms-and-sluggish-everywhere-else).

OECD (2016), OECD Regional Outlook 2016, Paris.

TORRES, R., and M. J. FERNÁNDEZ (2016), “The economic recovery: Short-term outlook and principal challenges,” Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook (SEFO), (5), September: 5-19.

Raymond Torres and María Jesús Fernández. Economic Trends and Statistics Department, Funcas