The reemergence of the spectre of EMU fragmentation: More debt and France in the eye of the storm

Economic and political instability, both domestically and globally, have led to increased volatility in EU sovereign risk premiums, with France particularly affected. While the EU’s flexible fiscal rules offer temporary relief, long-term fiscal reforms are necessary to address underlying imbalances and return greater stability to EU sovereign debt markets.

Abstract: Persistent domestic and global political instability, along with economic uncertainty, have driven volatility in sovereign risk premiums across the EU, with France being particularly affected. While the EU’s flexible fiscal rules offer some relief, underlying fiscal imbalances in several countries, including France, remain unaddressed. For example, France’s fiscal deficit increased to 5.5% of GDP in 2023, while its public debt-to-GDP ratio went from 65% in 2007 to 110% by the end of 2023. highlighting the scale of the problem. Addressing these challenges requires long-term fiscal adjustments to stabilize debt ratios and ensure sustainable fiscal management, especially for France. However, political fragmentation and polarization complicate the implementation of necessary reforms, heightening the likelihood of prolonged market volatility across EU sovereign debt markets.

Foreword

The legislative elections in France in June and July 2024, when the ultra-right party led by Marine Le Pen obtained its best result in its 40-year history, sparked a fresh episode of intense volatility in the eurozone sovereign debt markets. The political uncertainty and complicated fiscal situation in the second largest economy in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) rekindled fears of eurozone fragmentation. Nearly three years after the pandemic, several of the eurozone’s main economies are feeling the weight of high public indebtedness. France ended 2023 with a public debt-to-GDP ratio of over 100%, which is above the eurozone average. The reinstatement of the fiscal rules in 2025, albeit watered down, will require governments to work harder to reduce their deficits and rein in their debt. This paper explores the recent trend in France’s sovereign debt spreads along with those of certain periphery economies relative to the Bund and analyses the medium-term risks.

Volatility in the French sovereign risk premium in June and July 2024

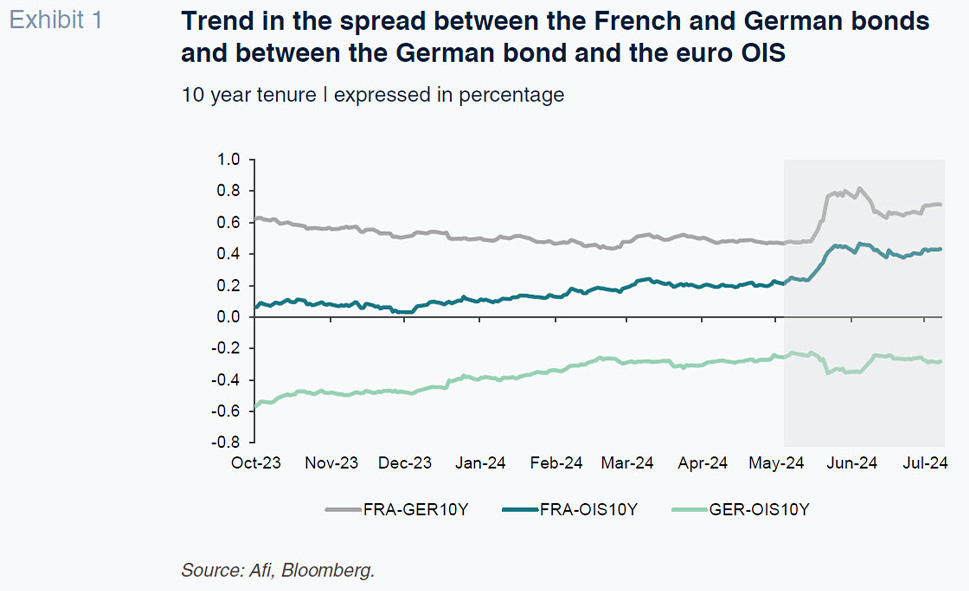

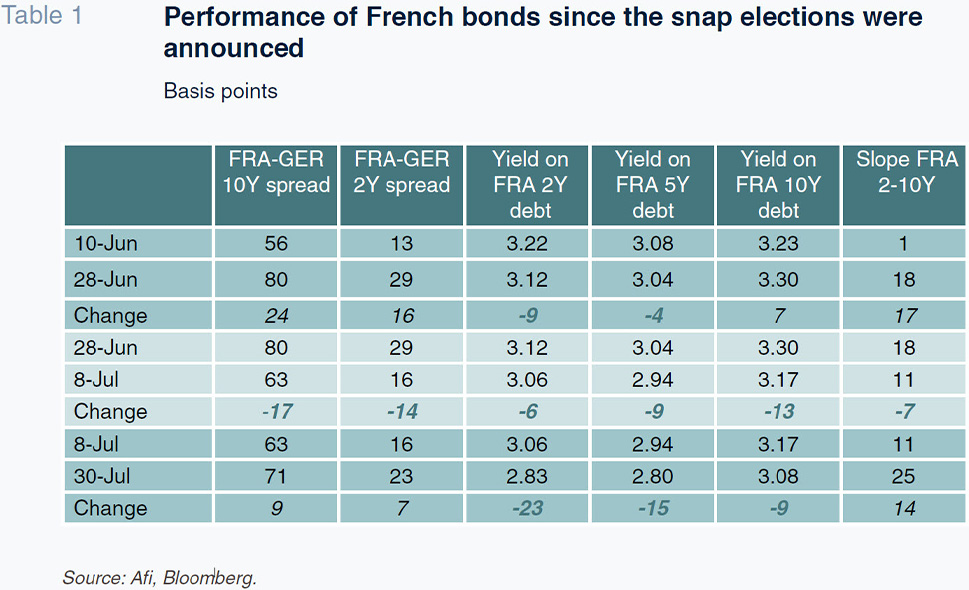

In the wake of the snap election called on 10 June and the strong inroads made by Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN or National Rally) at the recent European Parliament elections, French spreads experienced idiosyncratic penalisation. The risk premium relative to the 10-year German bond increased to 80 basis points on 28 June. Behind the run-up was growing concern about political and fiscal stability in France.

The RN obtained 34.2% of the votes in the first round (30 June), cementing its position as the country’s leading political force. The market responded by sending the OAT-Bund spread to 85bp.

During the days before the second round, the parties in third place in many electoral districts (mainly the New Popular Front (NFP) and the centrist alliance formed by Macron (Ensemble)) decided to withdraw their candidates in the districts in which the RN had won by a significant margin. The motive was to prevent the ultra-right party from winning an absolute majority by concentrating the vote against Le Pen in a single alternative, NFP or Ensemble. Although uncertainty was not fully dissipated by this play, the 10-year spread fell back to 63bp.

The second round on 7 July confirmed the existence of deep support for RN, which nevertheless failed to secure the absolute majority needed to form a government. The left-wing NFP leapt to first place, obtaining 182 seats (compared to 131 in 2022). Macron’s centrist alliance (Ensemble) also lost ground but managed to hold onto 168 seats, to leave RN in third position, with 143 seats, well below the 240 it was expected to pick up following the first round.

Despite side-stepping an absolute majority for RN, political uncertainty in France persists. Parliamentary fragmentation leaves the country paralysed unless a technocratic or coalition government can be formed. In sum, the results of the French elections leave the country in a state of considerable political uncertainty at a time when, as we will see, it needs to be taking important fiscal measures.

This uncertainty has affected French debt while also generating, temporarily, a ‘safe haven’: German debt (specifically, the 10-year Bund), for which the negative spread relative to the €STR OIS rate widened, while French debt became cheaper relative to both the Bund and the OIS. Other measures customarily scrutinised to track the risk of fragmentation in the eurozone, such as the ISDA [1] basis on French debt, rose as high as 20bp, while the relative penalisation of French equities intensified compared to other eurozone stock indices.

Statements by the members of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank played an important role in stabilising French bond yields between the first and second rounds of voting. Lagarde emphasised that the ECB was watching the situation in the sovereign debt markets closely, particularly movements in the French market. She underscored the ECB’s commitment to financial stability in the eurozone, reiterating that the ECB stood ready to intervene if necessary and stressing the importance of the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) in guaranteeing that the ECB’s monetary policy decisions are transmitted uniformly in all eurozone member states.

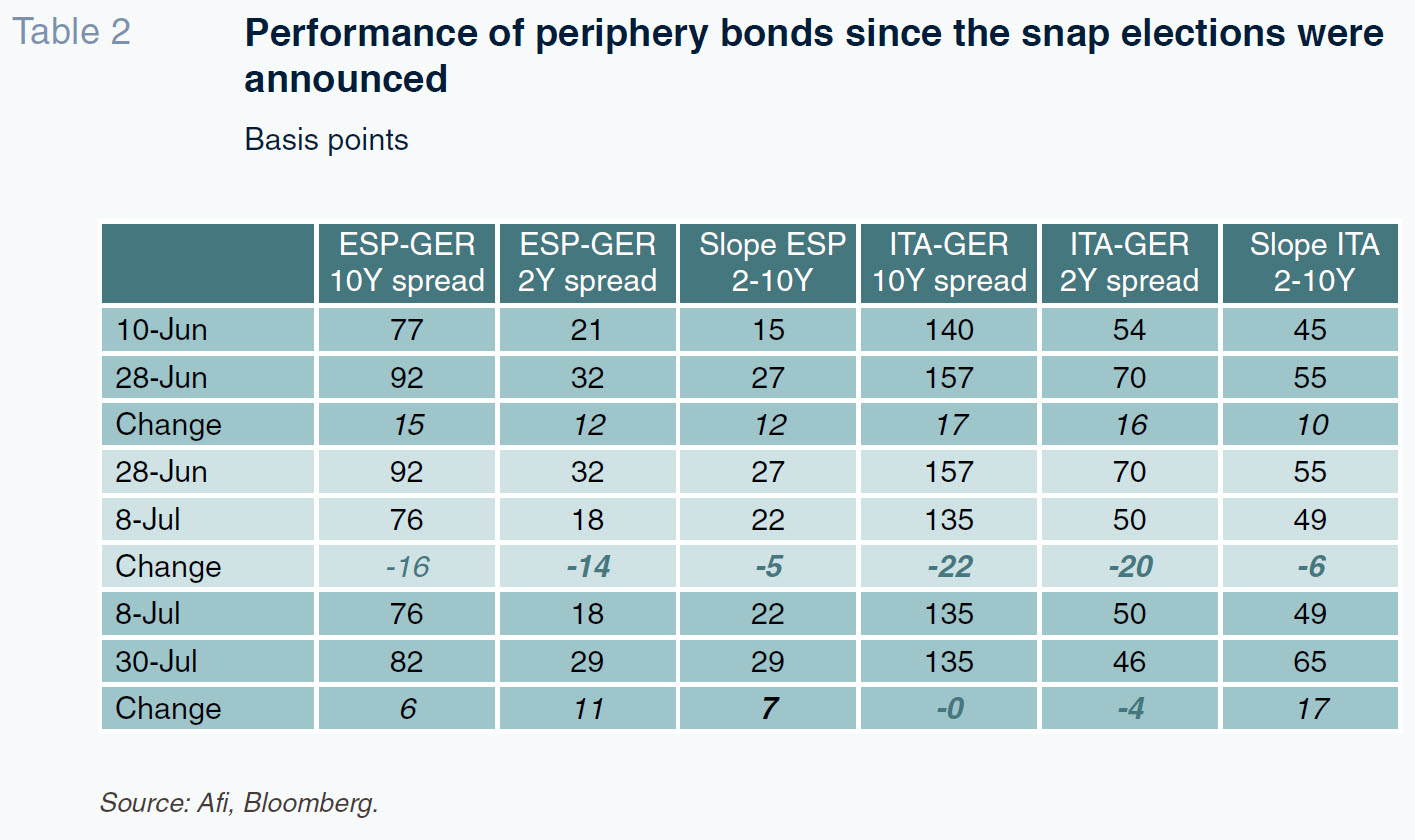

Limited contagion to periphery sovereign debt yields

The increase in the spread on French bonds had a limited impact on Spanish, Italian or Portuguese sovereign debt spreads. While the spreads did all move in the same direction, the scale of the widening and sensitivity of the peripheral countries’ spreads was moderate compared to the trend in French bonds. Perceived systemic risk did not hit alarming levels.

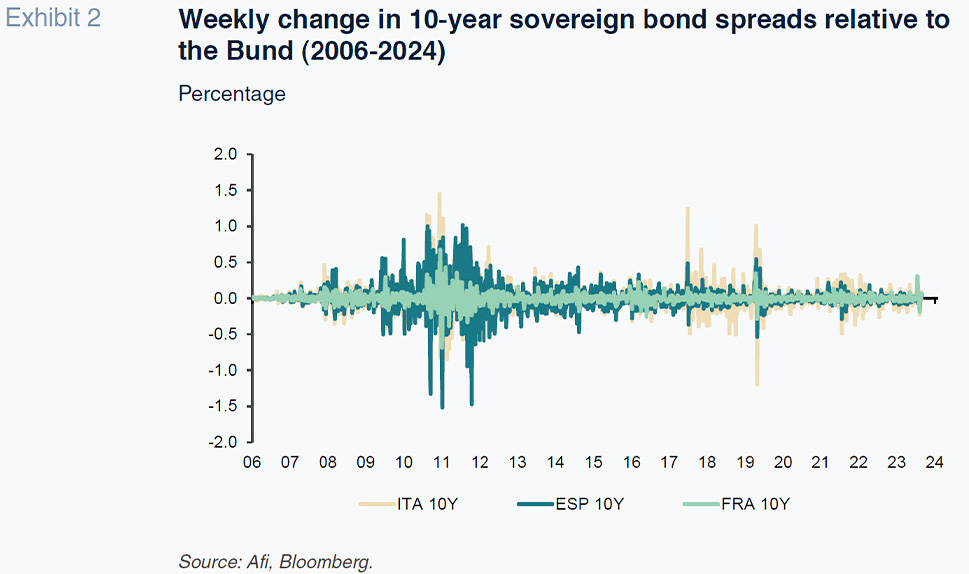

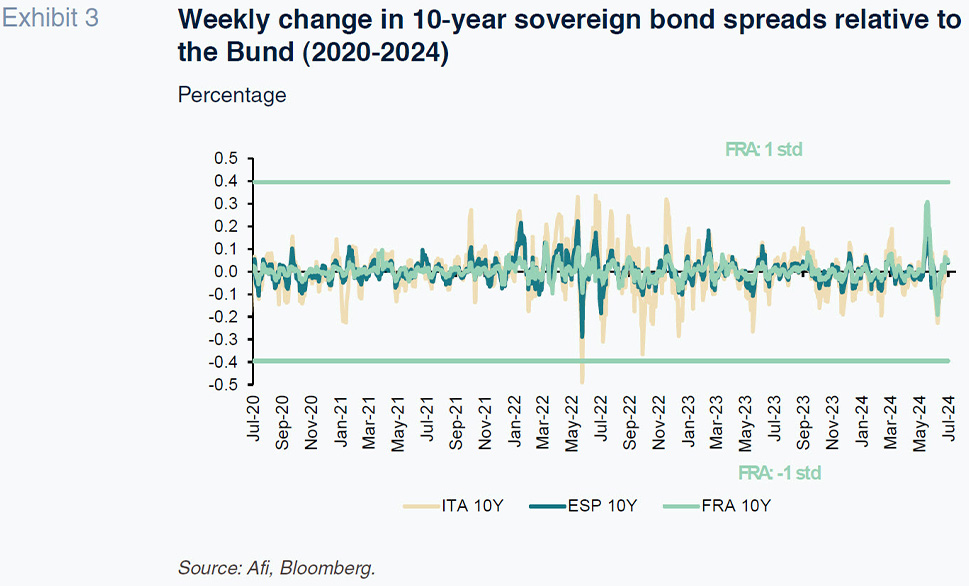

The scant contagion from the sovereign bond stress in France to other markets comes into focus if we compare the scale of the weekly movements in the various spreads relative to the German sovereign bond, measured in standard deviations, which were far more pronounced in France than in Spain or Italy. This evidences in our opinion, the idiosyncratic nature of the French problem and the low expectation of contagion to third countries. The movements observed in the spreads on this occasion contrast with what happened during the 2011-2012 sovereign debt crisis, the Italian political crisis of 2028, the onset of the pandemic in 2020 or Georgia Meloni’s ascent to the top government office in Italy in 2022. On all of those occasions the size of the movements in periphery debt spreads was much bigger than the oscillation in the French sovereign bond spread.

The trend in France’s macroeconomic and financial fundamentals over the past two decades reveals slow but steady deterioration, making the French economy look more and more like a eurozone periphery economy. Unlike Spain, Italy, Portugal, Greece and Ireland, which underwent boom and then bust between 2005 and 2013 and have since made significant adjustments, France has been far steadier but has etched out a path of constant deterioration, particularly in terms of its fiscal position.

For example, France’s fiscal deficit increased to 5.5% of GDP in 2023, while its public debt-to-GDP ratio went from 65% in 2007 to 110% by the end of 2023. As a result, France has converged towards a position in line with or worse than those presented by Italy, Spain and Portugal, whose debt ratios are similarly steep (137%, 107% and 99%, respectively in 2023). In 2023, the French economy registered GDP growth of 0.9%, which is well below the annual growth reported by Spain or Portugal, of 2.5% and 2.3%, respectively.

Modest economic growth combined with steep private sector leverage and considerably impaired fiscal ratios has undermined France’s perceived fiscal sustainability. Greater mistrust around the government’s ability to adequately manage the country’s public finances has translated into slow but steady widening in its sovereign debt spreads since 2021, as well as a drop in the country’s long-term sovereign debt credit ratings (S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings lowered their ratings from AA to AA- between 2023 and 2024).

The cost of servicing French debt, measured as interest payments over GDP, has fallen in recent years, in line with the trend observed across the eurozone. In 2023, France earmarked 1.7% of its GDP to interest payments, down from 2.5% in 2010. However, the debt service burden remains significant, especially compared with Germany, where interest payments were equivalent to just 0.9% of GDP in 2023 (compared to 2.5% in Spain and 2.2% in Portugal). France’s fiscal divergence from the eurozone core is clear.

The cost of France’s stock of debt decreased from 4.1% in 2007 to 1.6% in 2023, mirroring the favourable bond market conditions prevailing for much the period that followed the Great Financial Crisis, marked by asset repurchases by the ECB and zero or negative interest rates. However, the room for manoeuvre is much narrower now that rates have normalised at around 2.5-3.0%, threatening to reverse the trend in the cost of the country’s debt if the rate on new issues remains above the average cost of its debt, as was the case in 2023. The average life of France’s outstanding sovereign debt is relatively long, at around eight years, in line with the other member states, which implies moderate refinancing risk. Lastly, 57% of France’s debt is held by foreign investors (RoW – private) and 16% is in the hands of the country’s domestic banks, a situation which exposes it to the risk of alterations in capital flows in the event of high-volatility scenarios.

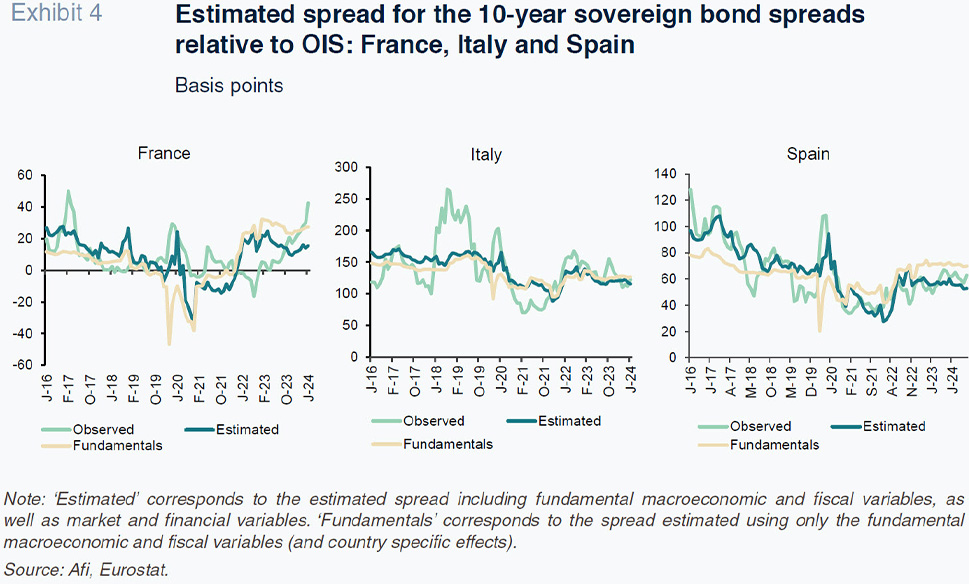

In an attempt to explain the extent to which the increase in the French country risk premium is attributable to the deterioration in its macroeconomic and fiscal fundamentals, we rely on the work of Burriel et al. (2024), estimating a model for the 10-year sovereign bond spreads for nine eurozone countries, using a sample that runs from January 2000 to June 2024. The model includes market and financial variables (such as the bid-ask spread for the sovereign bonds and the volatility index, VIX), in addition to macroeconomic fundamentals (market consensus forecasts for GDP growth, inflation, debt-to-GDP and the public deficit). We built an estimate of the spread using all of the variables included in the model and an estimate based on the fundamental value of the spread, i.e., consistent with the level of the growth and fiscal variables.

Exhibit 4 illustrates the actual spread observed, our estimate using the full model and our estimate of the fundamental value of the sovereign spreads for France, Italy and Spain. As already posited in the last section, increased fiscal imbalances and reduced growth expectations explain much of the increase in the French sovereign bond spread since mid-2022. Considering the estimate based on fundamentals over the course of 2023 further reinforces this idea. The widening observed in the French sovereign spread since May 2023 can be interpreted as an adjustment that is consistent with its ailing macroeconomic fundamentals. In Italy and Spain, whose spreads remain at higher absolute levels, the increase in estimated spreads is less pronounced.

Conclusions and thoughts looking forward

In a context of uncertain domestic and global political, geopolitical and economic stability, volatility in the risk premiums demanded to hold the sovereign debt of France and other eurozone issuers could become a recurring feature rather than a passing phenomenon. The EU fiscal rules due to be reinstated are laxer than they used to be and may give the member states a little more room for manoeuvre. However, this temporary relief does not resolve the underlying fiscal issues affecting several countries, including France. Implementation of fiscal adjustments at a time of economic cooling and/or greater political fragmentation could exert upward pressure on debt spreads. It is complicated by the difficulties in the formation of stable governments capable of implementing the necessary fiscal and economic reforms. As a result, periods of volatility in sovereign risk premiums may persist, requiring governments to focus on long-term solutions to stabilize their debt ratios and ensure fiscal sustainability. France will need to navigate these challenges with particular care.

Notes

The basis (bp) between the spread on the CDS (credit default swap) contract over French debt quoted on the 2013 definition, which contemplates redenomination into a currency other than the euro as a default event, relative to the 2004 version, which does not contemplate that eventuality as a default event.

References

BURRIEL, P., DELGADO-TÉLLEZ, M., FIGUEROA, C., KATARYNIUK, I., and PEREZ, J. (2024). Estimating the contribution of macroeconomic factors to sovereign bond spreads in the euro area. Working Papers, No. 2408. Bank of Spain.

José Manuel Amor, Camila Figueroa and Javier Pino. Afi