Rewiring the European Central Bank

On 13 March 2024, the ECB announced a new operational framework to manage its shrinking balance sheet, fundamentally altering its relationship with the banking system and financial markets. The major impact will be felt by 2026-2027 as the Eurosystem’s balance sheet decreases, requiring the ECB to adapt its monetary policy while preserving financial stability.

Abstract: The European Central Bank (ECB) announced on 13 March 2024 that it would adopt a new “operational framework” for controlling monetary policy. That decision was necessary because the ECB is allowing the assets it purchased and accepted as collateral in exchange for long-term refinancing operations to mature or be returned to the market. With a shrinking balance sheet, the ECB needs to change its relationship with the banking system. It will also change its relationship with non-bank financial institutions and with the financial markets for public and private securities. This transformation is not immediate. The major consequences will start to be felt only in 2026 or 2027. But it is imminent. As the collective balance sheet of the central banks that participate in the euro as a common currency, the Eurosystem, falls from just under €6.5 trillion today to something just over €3 trillion in 2026-2027, the ECB must find a new way to set monetary policy while at the same time preserving financial stability. The first major step took place on 12 September 2024 with a realignment of the ECB’s main policy rates. Important questions about future steps remain to be addressed.

Background

The European Central Bank – like all central banks – conducts monetary policy through the provision of “liquidity”. This liquidity is not like the currency used by non-bank financial institutions, firms, or households. It exists only as accounting entries that financial institutions officially recognized as “banks” can access on the consolidated balance sheet of the central banks that have adopted the euro as a common currency – the Eurosystem. That central bank liquidity plays a key role in the financial system because it is the only form of currency that banks can use to meet their regulatory reserve requirements. It is also the safest instrument for banks to use in meeting their regulatory requirements to maintain an adequate volume of highly liquid assets on their own balance sheets. Central banks conduct monetary policy by setting the volume and price of this liquidity. In doing so, they influence the level of activity in the financial system. Central banks also have a direct impact on the performance of non-financial institutions and the markets for tradable public and private securities. More fundamentally, central banks use their control over liquidity to influence the performance of the real economy both at discrete points in the business cycle, slowing down inflation or pushing up activity, and, at least potentially, in creating longer-term incentives for innovation and investment. Therefore, any change in the way central banks connect to the banking system has significant implications for the functioning of the euro as a common currency.

Introduction

The Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) has been wrestling with the challenge of reversing the instruments it deployed to fight the global economic and financial crisis for the better part of a decade (Jones, 2017). Initially, concern focused on the volatility that the ECB might introduce into financial markets. The Governing Council also worried that it might move too quickly in withdrawing monetary stimulus and so put a brake on the euro area’s fragile recovery. These concerns only increased during the pandemic and in the initial days after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

With the sudden acceleration of inflation, however, Governing Council members recognized that they would have to withdraw monetary stimulus to slow the growth of prices. They also recognized that reversing their monetary policy stance would change the way the ECB is connected to European banks and financial markets. As a result, the change in monetary policy would also have implications for the way monetary policy is conducted – the ECB’s “operational framework”. Hence, the Governing Council launched a 14-month-long review of its operations.

The Governing Council announced the first results of that review on 13 March 2024 (ECB, 2024). What it admitted is that the onset of the global economic and financial crisis had broken the old way central banks used to conduct monetary policy, and the monetary policy instruments used to respond to the crisis had created a new way of working that would be unsustainable over the longer-term. Hence, the ECB would have to find a new operational framework that falls somewhere between what monetary policymakers did in the past and what they had to do during the crisis. The problem is that many important details about how this new operational framework will function remain uncertain.

The goal is for the Governing Council to have effective control over monetary conditions that is resilient to changing circumstances. The challenge is that achieving that objective depends on many factors outside the Governing Council’s control. To understand why, it is necessary to consider how central banks are connected to the banking system, how that connection influences financial conditions more generally, and how that influence over financial conditions has an impact both on macroeconomic performance and on the structure of the real economy.

More than just a ledger

The distinctive feature of the European Central Bank – and any central bank, since the Bank of Amsterdam was founded at the start of the 17th Century (Quinn and Roberds, 2024) – lies in its ability to create money or liquidity by adding assets and liabilities to its balance sheet. The liquidity is not money in the conventional sense, although the ECB does have the ability to underwrite conventional currency as well. The difference is that ECB liquidity is available only to those institutions who are allowed to hold accounts on the balance sheets of those central banks that have adopted the euro as a common currency – the Eurosystem. Other financial institutions can tap the liquidity created by the ECB indirectly, through the banking system. But only banks have the ability to manage ECB liquidity directly. Indeed, qualification to access central bank liquidity is often what distinguishes a bank – in regulatory terms – from other financial institutions.

This focus on the balance sheet matters because of the way central banks like the ECB use access to their liquidity to influence monetary conditions more generally. When it started, the ECB gave banks access only to as much liquidity as they required to meet their regulatory obligations – auctioning off a fixed amount of liquidity set using estimates of what the banks would need over a specific “maintenance period” based on bids over prices and quantities made by individual institutions. This system allowed the Eurosystem to hold a relatively small collective balance sheet and it created strong incentives for banks to trade central bank liquidity with one another in the form of unsecured overnight lending during the liquidity maintenance period.

At the onset of the global economic and financial crisis, however, banks stopped trading with one another. As a result, the ECB’s old operational framework for managing monetary policy broke down. Other central banks had a similar experience (Buiter, 2021: 10-15). Banks struggled to meet their regulatory requirements during the liquidity maintenance period. Rather than force these institutions to take out penalty loans through its marginal lending facility, the Governing Council opted to change the way it lent out liquidity so that banks could borrow as much as they required at a fixed rate rather than having to bid at auction (Gotti and Papadia, 2024: 6).

This expansion of lending through the introduction of fixed-rate, full-allotment procedures inevitably expanded the balance sheet of the ECB with additional bank deposits on the liability side and lending to banks on the asset side. That expansion accelerated with the introduction of long-term refinancing operations and other forms of lending and with the relaxation of collateral rules that made it easier for banks to borrow central bank liquidity. But it also expanded as the ECB began to purchase assets outright both to stabilize particular asset classes like covered bonds and asset backed securities, and to provide additional liquidity to the banking system.

Such outright purchases are little different from the longer-term lending operations apart from the fact that the lending went only to banks while the purchases also involved non-financial institutions (Chadha, 2022: 143-146). The point to note is that even when the ECB purchased assets from non-bank financial institutions, the central bank liquidity remained within the banks with which those institutions did business. In turn, those banks amassed more central bank liquidity than they required to meet their regulatory obligations and which they left on deposit within the Eurosystem.

From one framework to another

This story is important because it explains why the Governing Council effectively developed a new operational framework during the financial crisis through which it began to influence monetary conditions both through quantitative easing – meaning expanding its balance sheet either through additional lending or asset purchases – and through changes in the rate it paid out on the deposit facility where banks parked their surplus liquidity. Within that new operational framework, banks have little incentive to engage in lending with one another to meet their liquidity requirements. Uncollateralized overnight bank lending has been replaced by collateralized lending either between banks or, increasingly, between banks and non-bank financial institutions (Schnable, 2023).

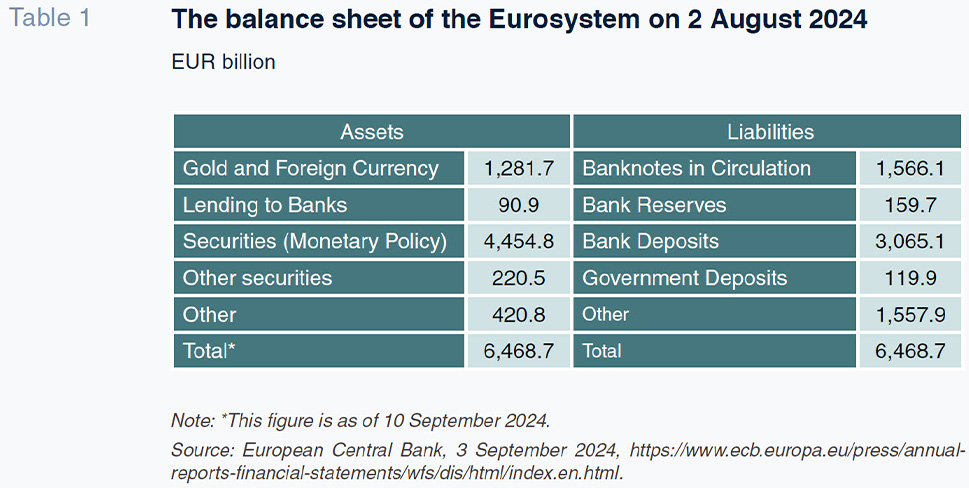

The results can be seen in the Eurosystem balance sheet (Table 1). The overall size of the balance sheet as of August 2024 is just under €6.5 trillion. On the asset side, €4.5 trillion takes the form of securities held for reasons related to monetary policy. Roughly €91 billion exists as lending to banks. Of that €76 billion comes from a targeted long-term lending operation that will mature in 2024, and only €2 billion comes out of the “main refinancing operations” that used to be the mainstay of the ECB’s operational framework.

[1]

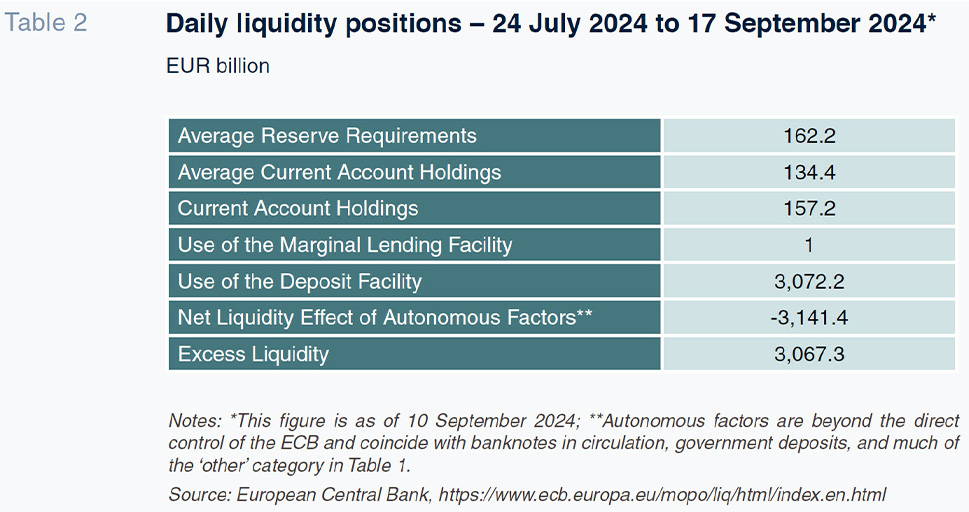

The reason can be seen on the liability side. The banks can easily meet their reserve requirements of just under €160 billion with the liquidity available. Indeed, there are just over €4 trillion held by banks within the deposit facility. Not all of this money on deposit is surplus liquidity. Some liquidity is necessary to offset other parts of the balance sheet beyond the control of the ECB. Nevertheless, the ECB estimates that just over €3 trillion of the deposit facility goes beyond the liquidity requirements for the Eurosystem (Table 2).

This balance sheet is smaller than it was in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, when the total volume of assets was more than €8 trillion. Of that total, €2.2 trillion were loans to banks as compared to €4.9 billion held in securities.

[2] These numbers have come down as the Governing Council allowed both the loans and securities to mature without replacing them. There is a point at which this shrinkage will start to push banks back into interbank markets to meet their regulatory liquidity requirements. Researchers at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have estimated that the tipping point will take place when surplus liquidity declines to around €1.3 billion, which could happen as early as 2026 (Brandoa-Marques and Ratnovsky, 2024: 25, 30); more recent estimates by researchers at Bruegel put the tipping point somewhere in a range between €1.3 trillion and €2 trillion, and have stretched out the timeline to 2027 (Gotti and Papadia, 2024: 2, 28).

Toward a new framework

Identifying this tipping point in the relationship between the provision of central bank liquidity and the use of interbank markets for liquidity redistribution matters because it is uncertain whether interbank lending markets will restart with the same depth and resilience as they had before the financial crisis either within euro area countries or, more important, across national boundaries. If those markets do restart, then it should be possible for the ECB to begin weaning euro-area banks off their dependence of the provision of abundant central bank liquidity.

Such a return of interbank lending would not allow the Eurosystem to shrink its balance sheet to the levels maintained before the financial crisis. The growth of items on the balance sheet beyond the direct control of the ECB has been too extensive. But it would allow the ECB to reduce its footprint in the market for public and private securities, which would release more collateralizable assets back into the market and so facilitate collateralized interbank lending. It would also remove some of the moral hazard created for banks that have relatively free access to liquidity without market discipline and for governments that know they can count on the Eurosystem to hold onto a large share of their government debt (Schnabel, 2024).

If interbank markets do not restart, then the ECB will have to be prepared to expand its balance sheet again to provide adequate liquidity either through long-term refinancing operations or through direct asset purchases (Gotti and Papadia, 2024: 18-19). The instruments created during the global economic and financial crisis are only being reset and not dismantled. Indeed, those instruments remain an integral part of how the ECB will operate even if there are not moments of acute stress.

The new operational framework the Governing Council is developing takes this requirement into account. It also builds on the recognition that the balance sheet will be larger than it was prior to the crisis. And it accepts the possibility that interbank lending will not develop to redistribute liquidity across

the banking system as efficiently as it did in the past. The Governing Council plans to use the deposit facility rate as its main instrument for influencing bank lending. It also plans to use a mix of long-term refinancing operations and outright asset purchases to create a structural portfolio of assets to ensure an adequate supply of liquidity on the liability side of its balance sheet (ECB, 2024). The details for this portfolio have yet to be worked out. The Governing Council plans to take that decision only in 2026, once the tensions in the banking system begin to emerge due to the relative shortage of surplus liquidity (Schnabel, 2024).

In the meantime, the Governing Council has decided to reduce the corridor between the deposit facility rate and its main refinancing operations from 50 basis points (or one half of one percent) to just 15 basis points (or 0.15 percent). That action took place at a monetary policy meeting on 12 September 2024. The reason is to ensure that if some banks find themselves running short of liquidity and yet unable to access interbank markets, they will not have to pay too large a premium to borrow what they need directly from the ECB in order to meet their regulatory requirements. This narrower corridor between the deposit rate and the rate charged on main refinancing operations should also reduce volatility of interbank lending rates by channelling any sudden stress on the banking system back to the ECB. That arrangement hews closely to recommendations made by the IMF even if the overall operating framework still contains significant ambiguities (Brandoa-Marques and Ratnovsky, 2024; Gotti and Papadia, 2024).

The future of the euro area

The hope is that the ECB will be able to implement this new operational framework without financial volatility or political opposition. So far, the Governing Council has been very successful in communicating its new policy without creating too many hostages to fortune. There are obvious sources of potential threat coming from the structural changes underway in the global economy. The introduction of new digital technologies is another potential source of instability (Gotti and Papadia, 2024). Nevertheless, the Governing Council has managed to shrink down its balance sheet and push back against inflation without facing a significant amount of turbulence. That might change and yet progress has been consistent.

Strong political opposition to the new framework also has not emerged. Some voices express disappointment that the pace of balance sheet reduction is too sluggish and stress that the goal should be to reinvigorate market forces by withdrawing the ECB from financial markets, but even traditionally conservate voices on the Governing Council have supported the new framework (Nagel, 2024). And while more activist voices worry that the smaller balance sheet will leave the ECB less room to promote other economic objectives – like the green transition – even they admit that the framework being proposed is better than the alternative of trying to maintain the arrangement that emerged during the crisis. There is still scope for improvement and yet that is no reason for opposition (Batsaikhan et al., 2024). Strengthening the relationship between the Eurosystem and the banking system it serves is too important.

Notes

References

BATSAIKHAN, U., DIESSNER, S., and SCHRÖDER BOSCH, J. (2024).

Future Fit Operational Framework for the European Central Bank. Manuscript, June.

BRANDOA-MARQUES, L., and RATNOVSHI, R. (2024). The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework: Corridor or Floor? [

IMF Working Paper]. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary fund, WP/24/56, March.

BUITER, W. (2021).

Central Banks as Fiscal Players: The Drivers of Fiscal and Monetary Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CHANDHA, J. (2022).

The Money Minders: The Parables, Trade-Offs and Lags of Central Banking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK. (2024). Changes to the Operational Framework for Implementing Monetary Policy.

Statement of the Governing Council. Frankfurt: ECB, 13 March.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2024/html/ecb.pr240313~807e240020.en.htmlGOTTI, G., and PAPADIA, F. The European Central Bank’s Operational Framework and What It Is Missing.’

Bruegel Working Paper, No. 17. Brussels: Bruegel, 16 July.

JONES, E. (2017). Now for the Tricky Part: Unwinding the European Central Bank’s Unconventional Monetary Policy Stance.

SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 6(3), 7-17.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/Migracion/

Articulos/FUNCAS_SEFO/031art02.pdf NAGEL, J. (2024). Reflections on the Eurosystem’s New Operational Framework.’ Speech. Frankfurt: Bundesbank, 16 May.

https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/reflections-on-the-eurosystem-s-new-operational-framework-932572SCHNABEL, I. (2023). Back to Normal? Balance Sheet Size and Interest Rate Control.’ Speech. Frankfurt: ECB, 27 March.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2023/html/ecb.sp230327_1~fe4adb3e9b.en.htmlSCHNABEL, I. (2024). The Eurosystem’s Operational Framework.’ Speech. Frankfurt: ECB, 14 March.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2024/html/ecb.sp240314~8b609de772.en.html

Erik Jones. Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies of the European University Institute