Spain’s fiscal consolidation: Situation and outlook

Although Spain’s deficit fell to 2.5% in 2018, projections for both the near and medium-term indicate more substantial consolidation is unlikely, leaving the Spanish economy vulnerable to potential scenarios of economic slowdown, interest rate hikes and financial turbulence. Spain’s deficit woes can largely be attributed to revenue rather than spending related issues, but any progress will require the support of Spanish citizens, who have tended to deprioritize fiscal matters.

Abstract: In 2018, Spain’s public deficit had fallen to 2.5%. While a welcome reduction, the result still fell short of the 2.2% target, placing the country two percentage points above the EU average. Moreover, Spain ranks as one of three countries with the highest structural deficits in the EU. This, coupled with a high debt-to-GDP ratio, leaves the Spanish economy vulnerable to potential scenarios of economic slowdown, interest rate hikes and financial turbulence. Unfortunately, future forecasts suggest the country is unlikely to see any significant improvement. The IMF estimates the deficit will remain above 2.5% for another four years with public debt exceeding 92% in 2024. Looking at the underlying causes reveals that Spain suffers more from a shortfall of revenue rather than a spending problem, and any potential strategy to address this will need to consider the available financial tools, institutional framework and political will. The latter point is a particular challenge given that latest polls show that Spanish citizens on average do not prioritize addressing the country’s fiscal problems.

[1]

Cutting the deficit: Slow and insufficient progress

On March 29th, 2019, Spain’s Finance Ministry announced that the country’s public deficit, expressed as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), stood at 2.63% at the end of 2018. Less than a month later, on April 23rd, Eurostat released its slightly stronger deficit calculation of 2.48%. The standard interchange of information and enquiries between Spain and EU authorities ultimately benefitted Spain, which is expected to be released from the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) this year. In 2018, the deficit narrowed by 0.6 percentage points from the 3.08% recorded in 2017. The final figure was also better than predicted by most independent observers and official forecasters, who, at the beginning of the year, broadly forecasted a deficit of 2.7% (Lago Peñas, 2019). The improved figures are mainly attributable to tax revenue, which grew more than expected during the final months of the year.

Regardless of this progress, the deficit still failed to meet the initial target for 2018 of 2.2%, nor was a significant reduction in public debt over GDP achieved.

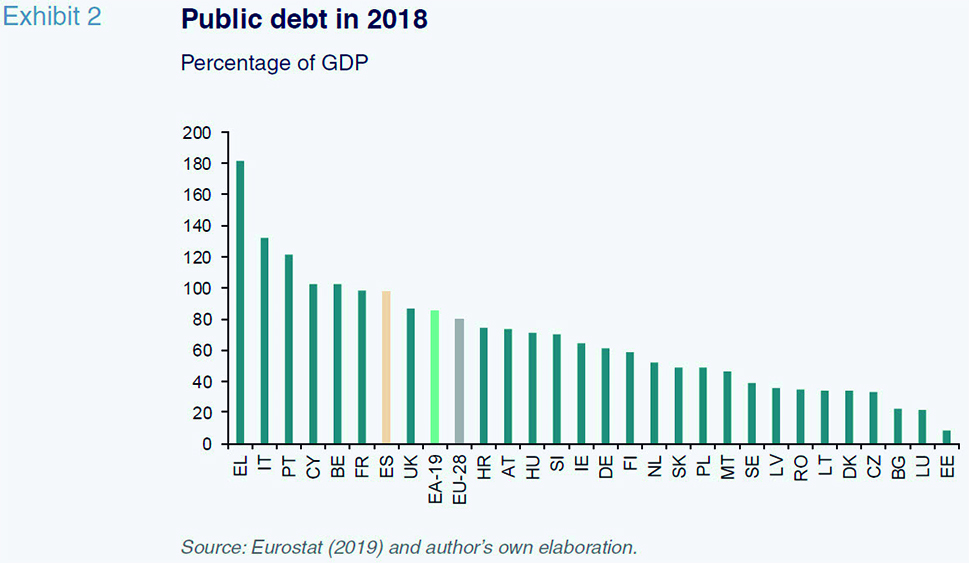

[2] According to 2019 Eurostat calculations, Spain’s public borrowings stood at 97.09% of GDP at year-end 2018, which is a scant one percentage point below the year-end 2017 figure of 98.12%. This is despite the Spanish economy continuing to post strong growth, indicating that public debt increased at almost the same pace as Spain’s robust economic expansion.

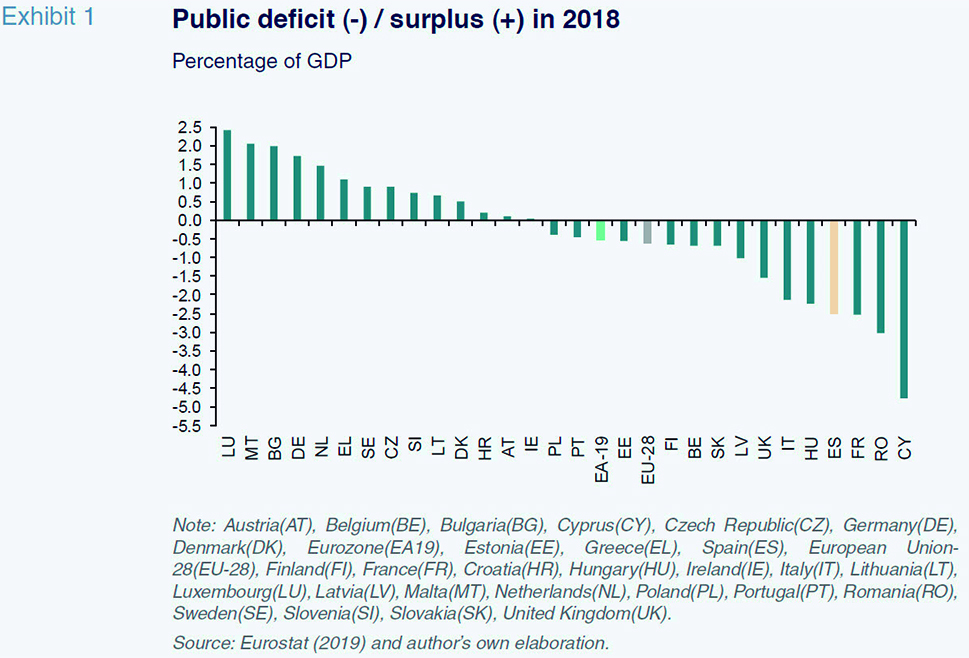

Exhibits 1 and 2 place the Spanish situation in the European context. In terms of the deficit, only three EU-28 member states ended 2018 in a weaker position than Spain. The average deficit in the EU-28 is just above 0.6% of GDP and below that in the Eurozone subgroup. Thus, in 2018, Spain’s deficit was nearly two percentage points higher than the EU average and over four percentage points greater than Germany, which posted a surplus that year. Similarly, Spain has one of the highest debt burdens in the EU-28, with only Greece, Italy, Portugal, Cyprus, Belgium and France faring worse by this measure.

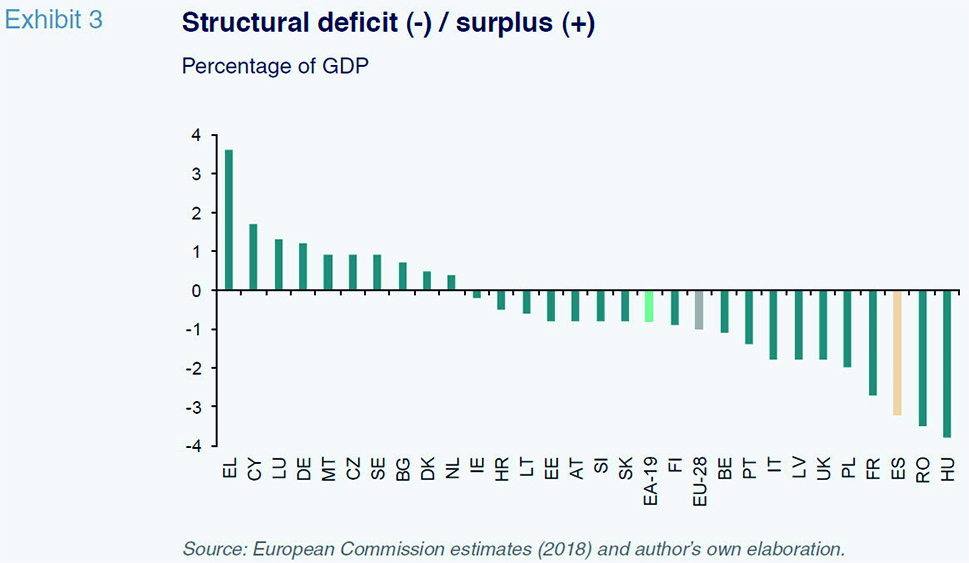

Exhibit 3 extends this analysis by highlighting Spain’s structural deficit. To single out the structural deficit, the cyclical component associated with the economic cycle, whether positive or negative, is eliminated. In contrast to the headline deficit, which is an accounting measure, the structural deficit is an estimate underpinned by the output gap concept. The different methodologies used do not always lead to the same conclusions. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine the cyclical situation at the end of the observed period. Often our perception of where an economy lies in its economic cycle changes after a few years thanks to the benefit of hindsight. With these caveats in mind, the most recent European Commission estimates rank Spain as one of three countries with the highest structural deficits in 2018. In Spain’s case, the cyclical adjustment is actually positive, so that its 2018 structural deficit is higher than the reported total of 3.2%. It is highly probable that this will come down somewhat when the estimates are revised in the coming months. However, Spain will still present one of the highest structural deficits within the EU-28.

In short, Spain’s public deficit is a problem. Spain suffers from an entrenched structural imbalance which is slowing the rate of public deleveraging. And a high debt-to-GDP ratio leaves the Spanish economy vulnerable to a potential economic slowdown, interest rate hikes and financial turbulence. Moreover, a structural deficit of over 2% greatly limits the ability to react to macroeconomic shocks. The effect of the automatic stabilisers would quickly push the deficit over 3%, making it impossible to roll out fiscal stimulus measures in response.

Short and medium term outlook

Despite the efforts made by the Ministry of Finance to ease the deficit targets for 2019, the target of 1.3% which still applies, reflects the figure set down in the General State Budget for 2018 (2018 GSB). The government is committed to ease the 2019 target to 2% (MHFP, 2019). Both recent electoral results (strengthening political parties supporting a relaxation of deficit targets) and non-official messages from the European Commission makes the adoption of this new target likely. However, the consensus forecast published by Funcas foresees a deficit of 2.3% (Funcas, 2019), with current forecasts ranging from 2.1% to 2.5%.

A more detailed analysis conducted by Spain’s independent fiscal institution, the AIReF, provides greater insight (AIReF, 2019a). The failure to enact the new budget for 2019 (2019 GSB) and the resulting rollover of the 2018 GSB is seen as good news in terms of the deficit prognosis, insofar as only some of the deficit-inflating measures contemplated in the draft budget have been set in motion. Layering in the fact that the deficit was ultimately somewhat lower than expected in 2018, the AIReF’s baseline scenario currently contemplates a 2019 deficit of 2.1%. AIRef views delivery of the official target of 1.3% as highly unlikely. Judging by its March forecasts, the Bank of Spain is less optimistic (Bank of Spain, 2019). Formulated before the definitive 2018 number was announced, the Bank of Spain has forecast a deficit of 2.5% in 2019, which would imply scant progress on the fiscal consolidation front and, given that real GDP growth is estimated at 2.2%, zero progress on reducing the structural deficit.

Turning to the medium term, the most recent reports are not optimistic. The IMF is projecting an overall deficit of over 2.2% and a structural deficit above 2.5% until 2024 (IMF, 2019). As a result, public debt would exceed 92% of GDP in 2024. These deficit projections are more pessimistic than those of the Bank of Spain (2019), which expects the deficit to trend gradually lower towards 1.8% in 2021.

The IMF’s debt projections are more in line with those of the AIReF (2019b). According to the fiscal body’s calculations, the debt ratio decreased from 100.4% to 97.2% between 2014 and 2018, representing a slight reduction of 3.2 percentage points of GDP. This is despite attributing a reduction of 14.8 percentage points to the sharp growth in the denominator throughout the period. The difference of over 10 percentage points can be blamed on the deficit, which continues to drive borrowings higher. The AIReF estimates that the debt-to-GDP ratio will hover around 91% in 2022, with a 25% probability that it fails to decrease at all. However, the European Commission is even more pessimistic than the IMF. Its projections put the debt ratio at over 96% in 2029, even in a scenario with relatively low interest rates and stable economic growth (European Commission, 2019b).

Why is Spain’s public deficit so high?

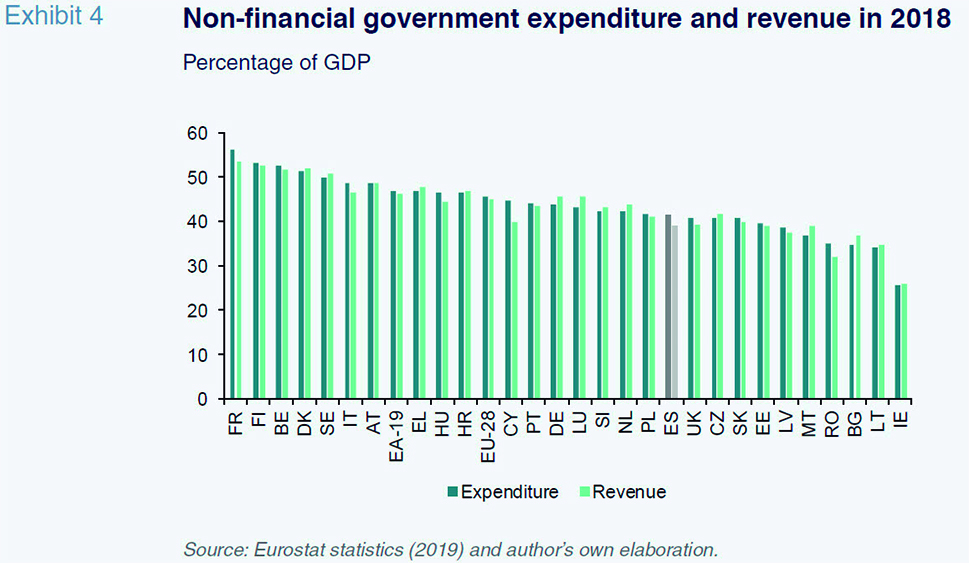

Exhibit 4 provides a glimpse into the causes of Spain’s high deficit. The exhibit depicts the ratios of non-financial government expenditure and revenue over GDP for the EU-28. The year of reference is 2018 and the countries are ranked in order of expenditure, from highest to lowest. Spain, which ranks eighteenth, has an expenditure ratio of 41.3%. This is 4.3 percentage points below the EU-28 average and 5.5 percentage points below the Eurozone average. The ten member states with lower spending levels include the Anglo-Saxon countries (UK, Ireland and Malta, a former British colony) and Eastern European countries. Excluding Romania, the ten countries with the highest imbalances all spend significantly more than Spain. Although the UK is similar in profile to Spain, its deficit was one percentage point lower than Spain’s in 2018. In short, the comparative European analysis reveals that the source of Spain’s high deficit lies more with a shortfall of revenue than an excess of spending.

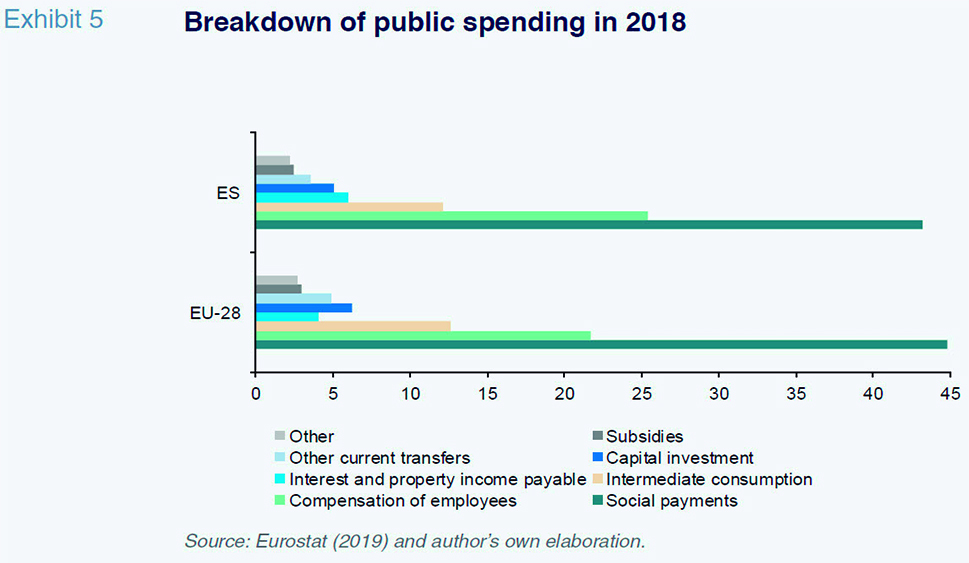

Exhibit 5 compares the public expense structure in Spain with the EU-28 average. It is worth highlighting the greater share of compensation, attributable to a higher propensity to produce certain labour-intensive public services, such as healthcare and education. Also noteworthy is the public sector’s higher interest burden due to its larger debt stock. Lastly, Exhibit 5 depicts Spain’s lower level of public investment, which is due to the government’s consolidation effort. Spain has fallen from being one of the countries with the highest levels of investment in infrastructure in terms of GDP to well below the EU average.

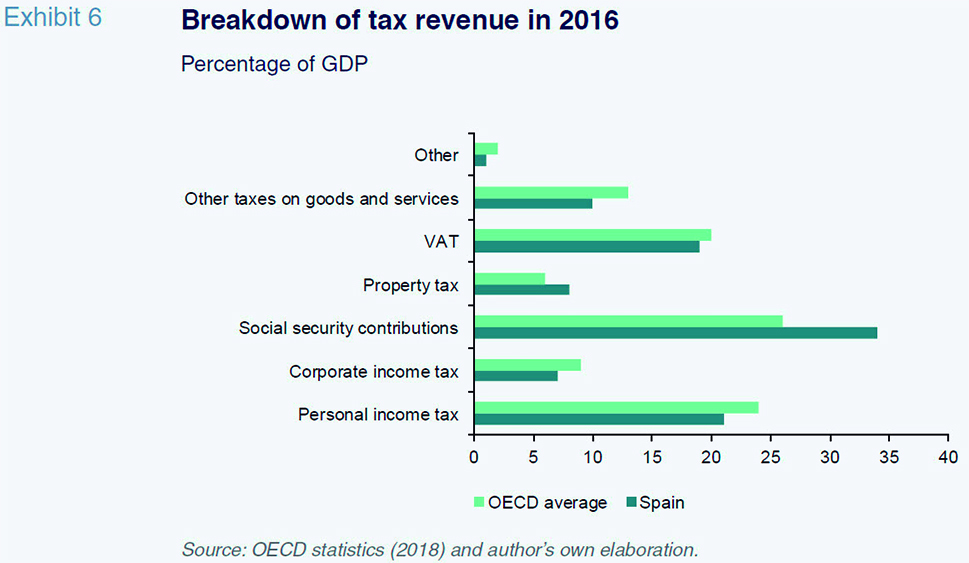

Meanwhile, Exhibit 6 presents the breakdown of tax revenue, compiled from 2016 data published by the OECD.

[3] Spain is clearly above the OECD average in terms of the weight of social security contributions and, to a lesser degree, property tax. However, the contribution of tax from consumption, personal income and corporate income tax are all below average. This can be explained by the existence of tax exemptions of all kinds rather than the tax rates themselves, which are generally speaking similar to those prevailing in the EU.

[4] All of this is compounded by the existence of a larger black economy and higher incidence of tax fraud.

[5]

What can be done to reduce the deficit?

Any strategy for reducing the structural public deficit in a meaningful and consistent manner must take into consideration three interrelated factors: (i) the institutional framework; (ii) the available financial tools; and, (iii) political will.

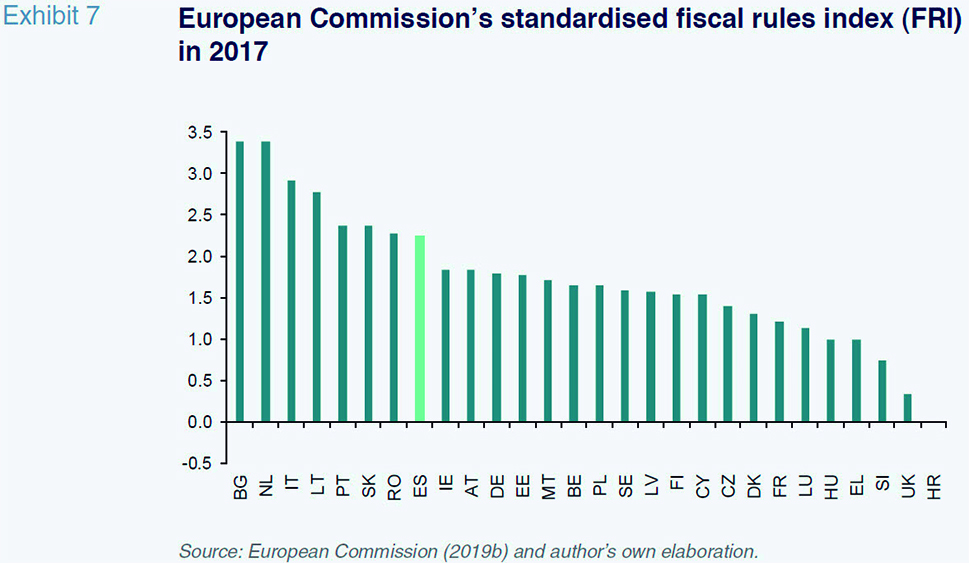

Starting with the institutional framework, the progress made in recent years has been commendable, as evidenced by the tightening of fiscal rules in both the European Union and Spain. To illustrate this quantitatively, we refer to the fiscal rules index (the FRI) calculated by the European Commission (European Commission, 2019b). The trend between 1995 and 2017 shows a substantial improvement in Spain in 2002 as a result of the budget stability rules introduced that year, as well as policy changes shaped by the EU from 2011 to 2014. Exhibit 7 shows that in 2017 Spain ranked eighth in the EU-28. It is therefore fair to say that Spain’s fiscal rules are neither the cause of nor the obvious solution to its public deficit issue.

[6] The data also fail to indicate any supervisory weakness when it comes to applying fiscal rules. The AIReF, which was established in 2014, has already made a considerable contribution to improving Spain’s finances and built a solid reputation for itself outside of Spain (Von Trapp

et al., 2017).

Regarding the available financial tools, the roadmap is clear-cut. Comprehensive tax reforms, coupled with a new paradigm for assessing the social return on public spending, would inject efficiency, equity and stability into Spain’s public finances. There is broad academic consensus on the need for such reforms and the general shape they should take.

Political will is one of Spain’s biggest challenges when it comes to tackling its deficit. Spanish society and its politicians frequently avoid the issue. Pointedly, neither the public deficit nor the public debt burden feature among the top 54 problems identified in the survey conducted by the Centre For Sociological Research (CIS) in February 2019. Only tax fraud makes a brief showing at the bottom of that list with 0.4% of Spaniards viewing tax fraud as one of Spain’s top three problems.

[7] Moreover, the opinion polls reveal that a clear majority of Spanish citizens are against introducing spending cuts and tax hikes to reduce the deficit (Calzada and Del Pino, 2018).

Spain’s politicians, regardless of where they lie on the political spectrum, face strong pressure to conform to these social demands. Putting control over the public deficit at the heart of their economic agendas and prioritising a balanced budget is unlikely to win votes. Spanish society still needs to face up to the fact that its troubled public finances present a serious problem.

Notes

I would like to thank Fernanda Martínez and Alejandro Domínguez for their assistance and Eduardo Bandrés for his input.

The Spanish Cabinet set the deficit target for 2018 at 2.2% of GDP on July 13th, 2017. That figure coincided with the forecast included in the first deficit and debt notification submitted to the European Commission on March 30th, 2018.

The Eurostat data (2019) do not permit such a detailed breakdown of tax revenue.

One European Commission study (European Commission, 2014) ranked Spain third among the 13 countries it analysed (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Italy, Greece, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, the UK and the US) in terms of tax exemptions as a percentage of GDP. Only Italy (8.1%) and the UK (5.9%) topped Spain (5.5%).

Unfortunately, there are no official, up-to-date estimates of the scale of these two problems. However, several studies put the size of Spain’s black economy above the OECD average (Lago Peñas, 2018). The empirical evidence regarding tax fraud points in the same direction but orbits almost exclusively around the estimates of the size of the black economy, providing limited insight

into the extent of the fraud. Consequently, any data analysis warrants a high degree of caution.

However, the Commission believes there is scope for a faster and automatic application of certain corrective mechanisms, as well as for a more efficient application of the spending rule (European Commission, 2019b).

References

AIReF. (2019a). Report on the Public Administrations’ initial budgets for 2019. Report 11/2019. Retrievable from www.airef.es— (2019b).

Debt Observatory. Abril 2019. Retrievable from

www.airef.esBANK OF SPAIN. (2018). Quarterly report on the Spanish economy.

Economic Bulletin, 1/2019. Retrievable from

www.bde.esCALZADA, I. and DEL PINO, E. (2018).

El peso de la opinión pública en las decisiones de ajuste del Estado de Bienestar: el caso de España entre 2008 y 2017 [The weight of public opinion in deciding to pare back the Welfare State; the case in Spain between 2008 and 2017]. In: F. CAMAS, and G. UBASART (Eds.)

Manual del Estado de Bienestar y las políticas sociolaborales [Manual of the Welfare State and social labour practices]. Barcelona: Huygens.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. (2014). Tax Expenditures in Direct Taxation in EU Members,

European Commission Occasional Papers, 207. Retrievable from

http://ec.europa.eu— (2018).

European Economic Forecast. Autumn 2018. Retrievable from

https://ec.europa.eu— (2019a).

Country Report Spain 2019 SWD (2019) 1008 final. February 27

th, Retrievable from

https://ec.europa.eu— (2019b).

Fiscal Rules Database, March 7

th. Retrievable from

https://ec.europa.euEUROSTAT. (2019).

Government Finance Statistics, April 23

rd. Retrievable from

https://ec.europa.euFUNCAS. (2019).

Spanish Economic Forecasts Panel, May. Retrievable from

www.funcas.esIMF. (2019).

Fiscal Monitor 2019. Curbing Corruption. April. Retrievable from

www.imf.orgLAGO PEÑAS, S. (Dir.) (2018).

Economía sumergida y fraude fiscal en España: ¿qué sabemos? ¿qué podemos hacer? [Black economy and tax fraud in Spain: What do we know? What can we do?]. Madrid: Funcas. Retrievable from

www.funcas.es— (2019). Deficit Reduction in Spain: Uncertainty Persists,

SEFO 8(1). Retrievable from

www.funcas.esMHFP. (2019). Kingdom of Spain Stability Programme Update 2019-2022. Available at:

www.mineco.gob.esOECD. (2018).

Revenue Statistics 2018. Spain. Retrievable from

www.oecd.org VON TRAPP, L., NICOL, S., FONTAINE, P., LAGO PEÑAS, S. and SUYKER, W. (2017).

OECD Review of the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF). Paris: OECD. Retrievable from

www.oecd.org

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics Research Network (GEN) at Vigo University