Interest rates and bank margins under protracted, exceptional monetary policy

In response to growing evidence of an economic slowdown, the ECB has announced plans to push back its rate increases and implement a new round of extraordinary liquidity measures, further complicating banks’ ability to raise their net interest income. Although the ECB could mitigate the negative effects of its monetary policy by creating a tiered deposit facility rate, such action would interfere with the central bank’s forward guidance.

Abstract: In March 2019, the ECB announced it would halt the dismantling of its quantitative easing program, leaving the interest rates for the main refinancing operations, marginal lending facility and deposit facility unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.40%, respectively. Additionally, the ECB has announced the launch of a new round of its targeted longer-term refinancing operations programme (TLTRO). This decision represents a marked shift from autumn 2018 when the ECB indicated it was ready to adopt a more hawkish stance. However, stagnant economic data and a tightening of credit mean interest rates are now unlikely to rise before 2020. This prolongation of exceptional monetary policy has put downward pressure on eurozone banks’ margins, leading some analysts to argue in favour of a tiered deposit facility rate to ease the burden on banks. Notably, the ECB remains unconvinced of this measure’s merit as it would undermine its forward guidance. Nevertheless, the ECB is likely to provide greater clarity on these issues as economic developments play out in the US and additional details over its new TLTRO-III programme are disclosed later this year.

Introduction

The European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policy has garnered a significant amount of controversy concerning both its alleged benefits and disadvantages. Although the ECB’s mandate to control inflation makes this dispute seem somewhat moot, it is impossible to overlook the importance and exceptional nature of monetary policy in the wake of the financial crisis. These policy decisions have generated two primary concerns. Firstly, there is the possibility that these policies are distorting the allocation mechanisms intrinsic to a market economy. Secondly, it may prove difficult to rollback these measures to achieve ‘monetary policy normalization’.

In autumn 2018, the ECB announced the gradual withdrawal of its asset purchase programme (APP), which had become a liquidity benchmark and a panacea in the bond markets in recent years. As a result, observers expected the ECB would subsequently adopt a more hawkish approach to monetary policy. However, the first quarter of 2019 showed signs of an economic slowdown in both the US and the eurozone, prompting the regions’ respective monetary authorities to halt the unwinding of quantitative easing (QE). This policy shift is evidenced by the decision to delay interest rate hikes and the maintenance of substantial liquidity injections. Unlike in the eurozone, expectations in the US shifted within a few short months, with some market observers now anticipating a fresh round of rate cuts by the Federal Reserve this year. Conversely, the underlying fundamentals of the eurozone economy suggest there is limited room for near-term rate cuts, as that could usher in a period of negative nominal benchmark rates. That said, the expected timing of rate increases has been pushed back until at least 2020. Additionally, there are plans to implement a new targeted longer-term refinancing operations programme (TLTRO III) in September 2019.

Under these circumstances, it is worth considering whether an indefinite period of a zero benchmark rate will disrupt financing flows and banking activities in the eurozone. In order to answer this question, it is necessary to analyse how the monetary environment may be affecting banks, particularly the flow of credit to the private sector and the banks’ ability to generate margins. Such analysis is relevant not only in microeconomic or corporate terms but for macroeconomic and macroprudential reasons, as the banking sector is crucial for orienting and stimulating investment.

Monetary policy decisions: Extension of QE

During the first quarter of 2019, the main multilateral economic organisations and forecasters issued warnings of an impending global economic slowdown. While this slowdown’s timing and intensity differed across regions, the continuing strength of US stock markets is still noteworthy, especially given the role of exogenous factors such as tax cuts. However, the Federal Reserve has also supported the stock market’s rally through its more accommodative, wait-and-see policy stance. At a meeting held on March 7

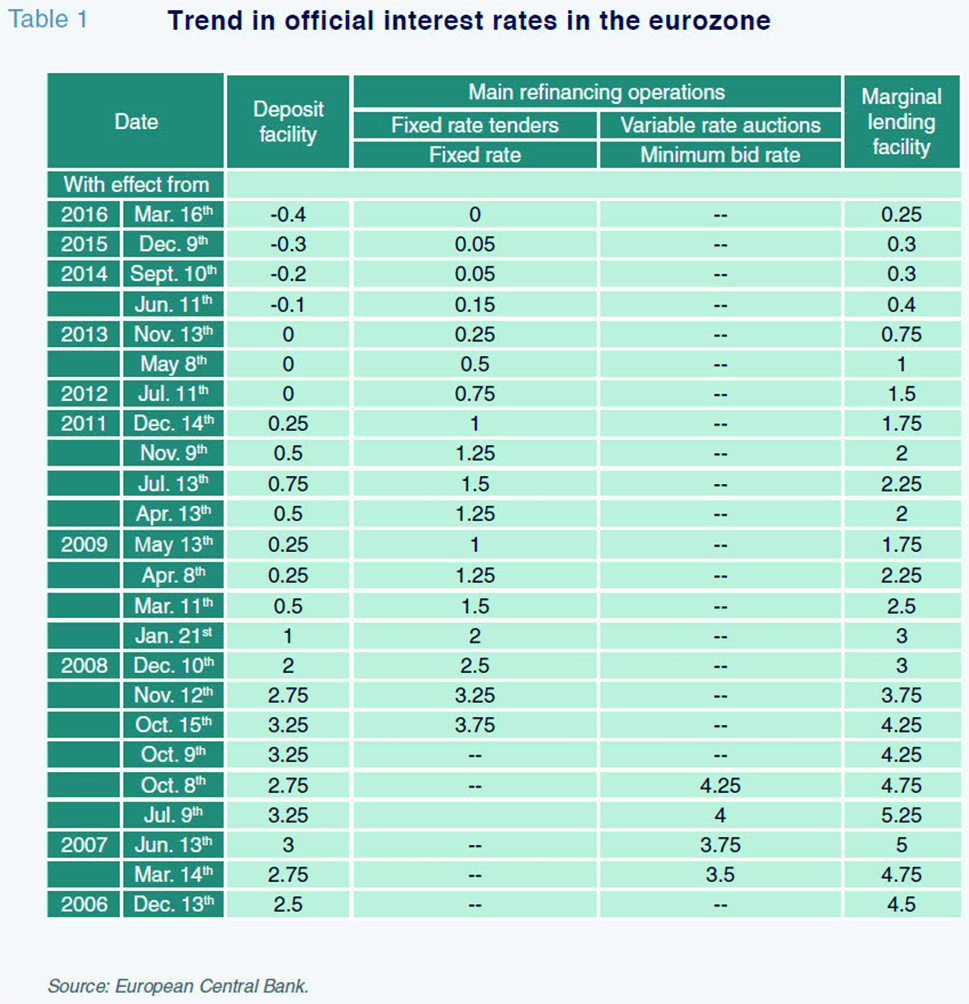

th, the ECB announced it would halt its dismantling of QE. The ECB’s Governing Council decided to leave the interest rates for the main refinancing operations, marginal lending facility and deposit facility unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.40%, respectively. These rates have remained steady since March 16th, 2016 (Table 1).

The ECB’s Governing Council said it expects “the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present levels at least through the end of 2019, and in any case for as long as necessary to ensure the continued sustained convergence of inflation to levels that are below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.”

[1]

This is broadly equivalent to an extension of its QE effort, particularly in light of two other measures announced. Firstly, the ECB intends to “continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the asset purchase programme for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation”. It also confirmed plans to introduce a new series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO-III), the terms and conditions of which have yet to be defined. The new programme is scheduled to begin in September 2019. As discussed in the next section, these operations are designed to prop up a minimum flow of credit, which has weakened in recent months.

Through the enactment of these policies, the ECB has extended the liquidity available to the banking sector and undermined expectations of rate increases in the near term. However, eurozone banks are adversely affected by the prolongation of QE. During its press conference on April 10

th, the ECB explained that “in the context of our regular assessment, we will also consider whether the preservation of the favourable implications of negative interest rates for the economy requires the mitigation of their possible side effects, if any, on bank intermediation.”

[2] However, the probability that the ECB enacts any policy changes that support banks’ profitability seems unlikely in the near term. The banks had hoped that with official benchmark rates remaining at 0%, the ECB might reduce the impact of the negative deposit facility rate (-0.40), which the ECB charges on cash surpluses held with central banks. Much of the current debate in the banking sector is centred around determining the extent to which the deposit facility’s interest rate can be increased to support banks’ profitability. One of the primary solutions posited by analysts is the creation of a tiered deposit system under which some of the cash on deposit would be charged a lower rate of interest or none at all. In some cases, central banks could even offer remuneration for cash held. It is estimated that the eurozone banks are paying 7.5 billion euros of interest on the deposit facility. By comparison, US banks currently earn interest on their excess cash, with estimates suggesting remuneration could reach 40 billion dollars in 2019.

It is worth highlight that previous experiences with tiered deposit rates in Japan and Austria occurred under different monetary contexts and with broader objectives such as the maintenance of interest rates. One of the main reasons for the ECB’s reluctance is that an increase in the deposit facility rate could send the wrong signal regarding the future direction of interest rates, which would be problematic given recent announcements that rates would remain unchanged until 2020.

Credit and bank margins: Scant room for manoeuvre

The ECB’s monetary policy measures, especially the new TLTRO-III, are designed to stimulate lending at a time when the eurozone economy has stagnated. The ECB stated on April 10

th that the “the annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations has moderated in recent months, reflecting the typical lagged reaction to the slowdown in economic growth. At the same time, the annual growth rate of loans to households remained broadly unchanged at 3.3% in February.”

[3]

In its April 9

th bank lending survey for the first quarter of 2019

[4] the ECB stated that the “monetary policy measures, including the new series of TLTROs that we announced in March, will help to safeguard favourable bank lending conditions and will continue to support access to financing, in particular for small and medium-sized enterprises.” However, demand appears to have waned in the first three months of the year. Whereas at year-end 2018, the banks were expecting to increase their lending by 9% year-on-year in 2019, the March surveyed indicated that the banks’ now anticipate credit growth to stagnate at 0%. The ECB believes that if the current longer-term operations mature (as is the case of most of the loans under the last programme, TLTRO-II), a new series of TLTRO will be needed to keep the current flow of credit going. That opinion has been reinforced by the feedback received from the banks in the lending survey. The banks stated that the TLTRO and asset purchase programmes have facilitated the growth in lending by easing their credit terms and conditions.

In Spain, the bank lending survey shows a tightening of both the supply and demand for credit. This data correspond with the broader trend across the eurozone, as well as revealing a slight contraction in credit. Specifically, bank loans to enterprises declined by 1.1% year-on-year in February. The stock of loans for house purchases similarly decreased by 1.1% year-on-year in February. In contrast, “other loans”, essentially consumer credit, increased by 5%. However, the sum of the two effects was an outflow of financing for households of 1.57 billion euros in February.

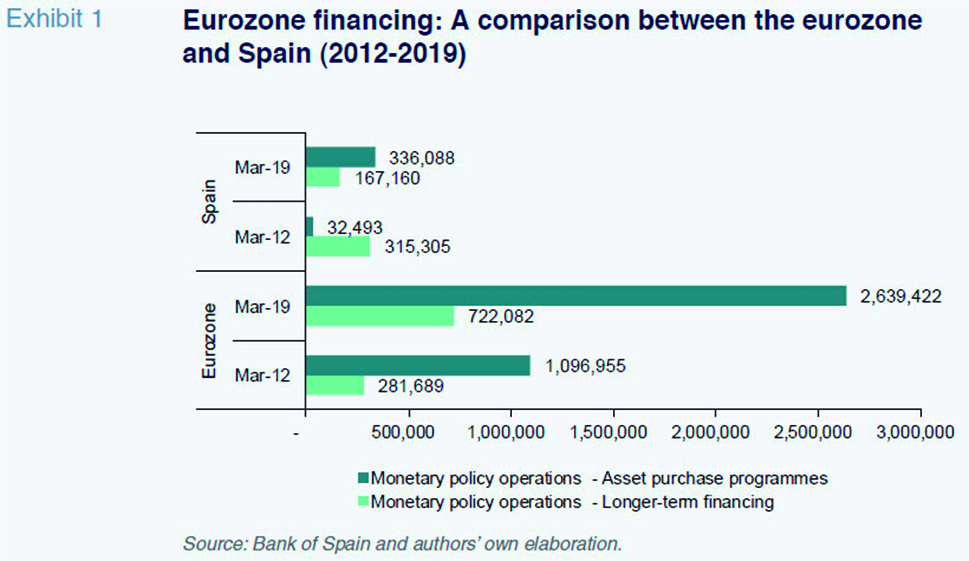

Since the QE programme continues to provide sufficient funds, the banks’ central issue does not lie with their liquidity levels. As shown in Exhibit 1, eurozone banks have increased their use of the ECB’s longer-term refinancing operations from 281.69 billion euros in March 2012 to 722.08 billion euros in March 2019. The Spanish banks account for 23.14% of that financing. However, it is the asset purchase programme, which has increased from 1.09 trillion euros in the eurozone in March 2012 to 2.64 trillion euros in March 2019, that represents the core of the QE effort. The Spanish banks account for 12.73% of this financing.

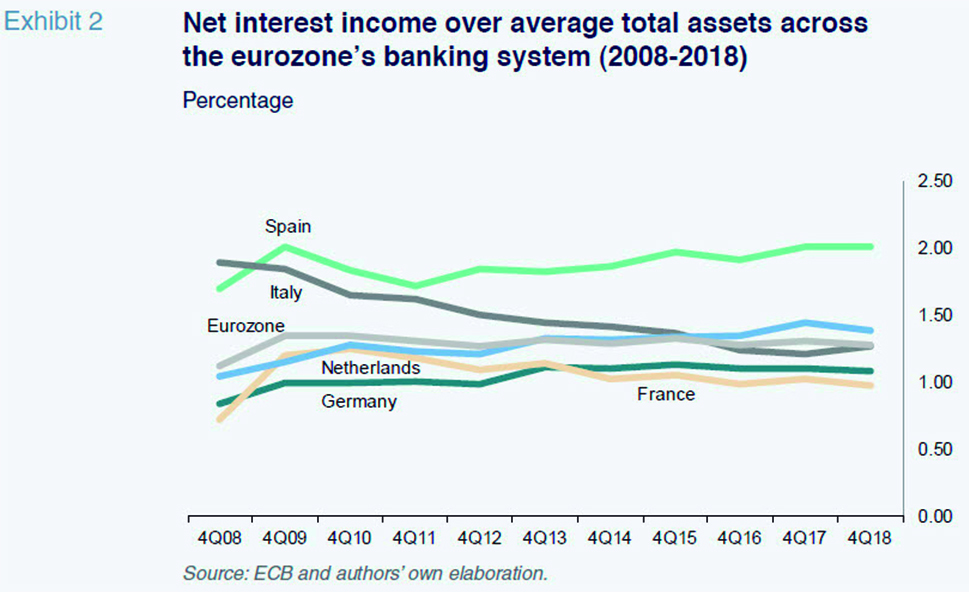

These trends in credit, liquidity and interest rates have taken a toll on banks’ margins, which, as shown in Exhibit 2, have flattened over the past 10 years. Volume-wise, however, the contribution by net interest income in 2008 is not comparable to that of 2018 as today’s European banking system is smaller and far more regulated. The combined effect has been to lower business volumes and returns on equity. That said, Spanish deposit-takers represent a slightly higher percentage of net interest income to average total assets than their European counterparts.

Although it is hard to empirically quantify the transmission of official interest rate cuts to bank margins, multiple recent studies

[5] suggest that a reduction in the central bank’s price of money adversely affects the banks’ net interest margins and returns on equity (ROE), although the effect is not linear. Moreover, the estimated adverse impact is higher when interest rates are unusually low.

Conclusion

Today, the relationship between the banking sector and monetary policy is heavily influenced by the persistence of exceptional liquidity conditions. The statements issued by the ECB in the aftermath of its April Governing Council meeting suggest that ultra-low interest rates may be adversely affecting financial intermediation. Nevertheless, the central bank’s mandate means that macroeconomic conditions (inflation) must take precedence over sector-specific considerations (bank profitability).

It is conceivable that the ECB will continue to assess the possibility of a tiered deposit facility rate. This arrangement would enable the banks to pay less and earn more on their excess cash. Implementation of such a scheme will depend largely on the direction taken by the ECB’s forward guidance. Specifically, the ECB may not alleviate pressure on the deposit facility until it has a clearer picture of when it can begin to raise interest rates.

Monetary decisions in the US will also influence the ECB’s policy. If the risk of a recession increases and the Federal Reserve cuts its benchmark rate, the ECB will experience even greater pressure to leave rates untouched.

It is possible that the ECB’s forward guidance will provide fresh insight into this issue towards the summer when it is due to disclose the terms and size of the announced TLTRO-III programme. At that point, the macroeconomic circumstances on both sides of the Atlantic may offer more clues as to what sort of policy scenario is likely to emerge.

Notes

For a synopsis of those studies, refer to PÉREZ MONTES, C. and. FERRER PÉREZ, A. (2018). The impact of the interest rate level on bank profitability and balance sheet structure. Financial Stability Review, 35, November, pp. 123-152.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. CUNEF, Bangor University and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas