Economic forecasts for Spain: 2019-2021

Available information for the first quarter of 2019 indicates that the Spanish economy performed stronger than many analysts had predicted, with GDP growing by 2.4% and employment extending its strong expansion. While forecasts suggest that unemployment will continue to decline, GDP growth is likely to decelerate due to less robust domestic demand and the potential prolongation of trade tensions -one of the main risks to these projections.

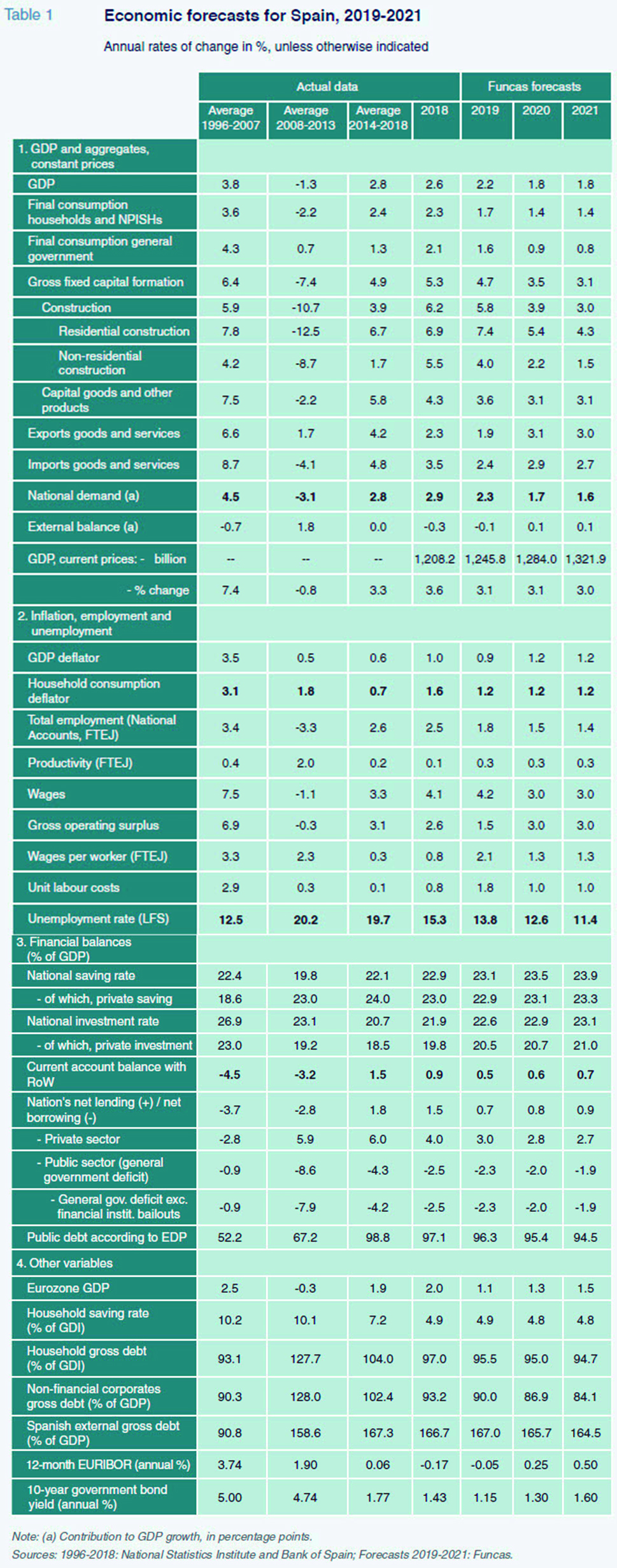

Abstract: The Spanish economy’s performance in 1Q2019 was stronger than projected, with GDP expanding by 2.4%, up 0.1 percentage points from the previous quarter. Additionally, provisional national accounts indicate a recovery in the industrial sector, after two weak quarters. There were also broadly positive developments in the labour market. Compared to last year, the number of full-time equivalent jobs increased by 510,000. Importantly, the unemployment rate has continued to decline to 14.7%. Less upbeat were the private consumption figures, which fell in real terms, signalling a modest deceleration of demand. In addition, the current account surplus has declined, while the public deficit has been reduced somewhat. Looking forward, we expect that the unemployment rate will eventually fall to 11.4% in 2021 alongside an expansion of GDP of 2.2% in 2019 and 1.8% for both 2020 and 2021. The slowdown in growth is the result of a loss of momentum across all components of domestic demand, as well as a reflection of the risks associated with the ongoing global trade tensions. Lastly, it is also unlikely that the public deficit will come down substantially. In this context, public debt would also not decline much, falling to 94.5% by 2021, around 2.6 percentage points below the 2018 figure.

Recent performance by the Spanish economy

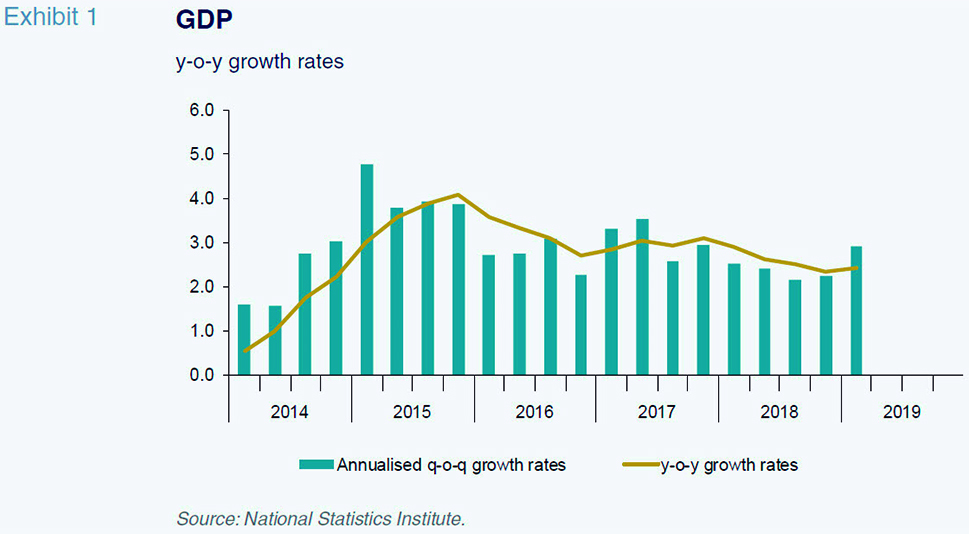

The provisional national accounts for the first quarter of 2019 point to quarter-on-quarter GDP growth of 0.7%, marking a slight slowdown from the rates observed throughout 2018. In year-on-year terms, the Spanish economy expanded by 2.4%, up 0.1 percentage point from the previous quarter’s figure. In short, these data present a better than forecast start to the year, albeit foreshadowed by economic indicators released over the past few months (Exhibit 1).

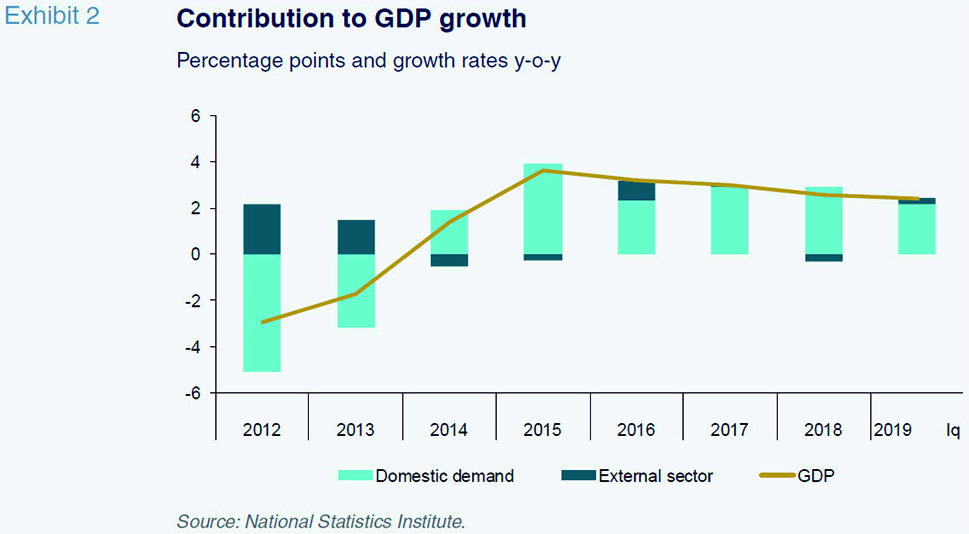

Domestic demand contributed 0.5 percentage points to the quarter-on-quarter growth (vs. 0.3pp in 4Q18), while foreign demand increased GDP growth by 0.2 percentage points (Exhibit 2). The uptick in domestic demand stemmed entirely from investment in capital goods, which recovered from the contraction sustained in previous quarters. The rate of growth in private consumption eased somewhat, though the slowdown was more pronounced in nominal terms due to its negative deflator. As a result, private consumption eased in real terms, despite the reduction in inflation. Additionally, growth in public consumption was stable, and investment in housing construction remained dynamic. Irrespective of the uptick in the first quarter, the trend in domestic demand is one of modest deceleration.

As for the foreign sector, the positive contribution to growth was the result of a bigger contraction in imports than exports. Shaped by lethargic growth in Europe, exports performance was weak, which is in line with trends in global trade.

From an industry perspective, the provisional national accounts point to a recovery in the industrial sector after two weak quarters. The biggest improvement was observed in the construction sector, while services remained stable.

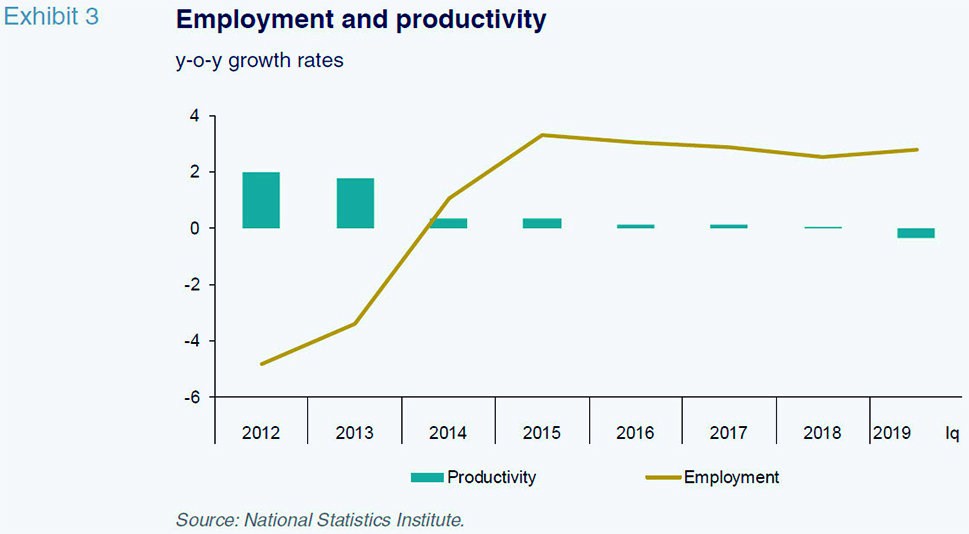

Employment measured in terms of full-time equivalent jobs saw impressive growth. Its expansion was slightly above GDP growth, which means that productivity continued to fall, albeit registering gains in the manufacturing sector (Exhibit 3). Compared to the first quarter of last year, the number of full-time equivalent jobs increased by 510,000. Average pay per job-holder accelerated, mainly due to wage growth in the public sector. As a result, growth in unit labour costs for the overall economy picked up speed to reach 1.7% year-on-year, a figure topped only in one quarter since the end of the last period of growth (4Q13). Nevertheless, in the manufacturing sector, unit labour costs declined.

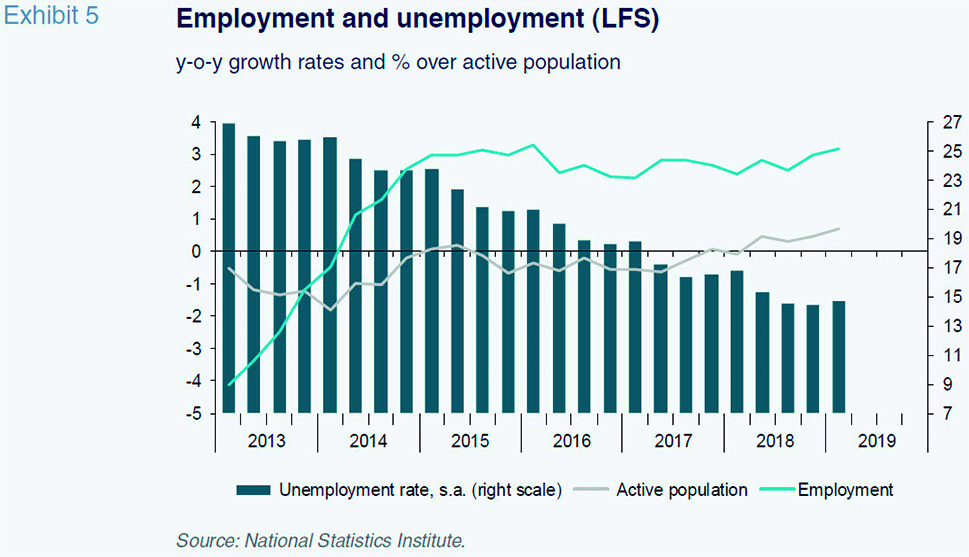

According to the Labour Force Survey (EPA for its acronym in Spanish), the working age population continued to increase in the first quarter of the year, thanks to sharp growth in foreign arrivals. As a result, the active population, which in 2018 increased for the first time after five years in decline, experienced further growth in the first quarter. The rate of unemployment declined to 14.7%, two percentage points below that of 1Q18 (Exhibit 5).

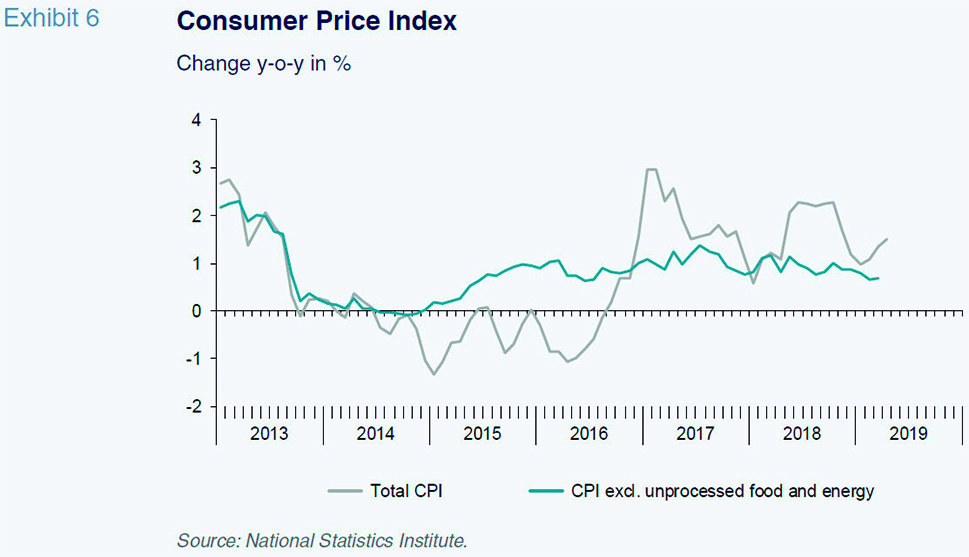

Prices have been subdued year-to-date. The headline inflation rate was 1.1% overall in the first quarter and core inflation was 0.7% (Exhibit 6). In harmonised terms, both rates were below the eurozone averages.

Turning to the start of the second quarter, the few indicators available so far show a deterioration compared to the first-quarter averages. Although the April manufacturing PMI reading improved slightly, the services PMI deteriorated sharply, as did the economic sentiment index. The confidence indicators have also weakened. However, job creation has remained strong. Judging by the Social Security contributor numbers, growth in April was similar to the already intense expansion recorded in March, without showing signs of any imminent slowdown.

The public deficit, including all levels of government except for the local authorities, increased by 1.5 billion euros year-on-year in January and February. This expansion was shaped by slower growth in revenue compared to expenditure. The deterioration is primarily observed at the central government and Social Security levels. On the spending side, it is worth highlighting the growth in wages as a result of increases in public sector wages, as well as an expansion in social welfare, due to pension increases and higher payments to the EU. On the revenue side, social security contributions increased sharply on the back of the increase in tax bases, while receipts from income taxes have dropped, though this is based on the initial months of the year, which are always meaningful.

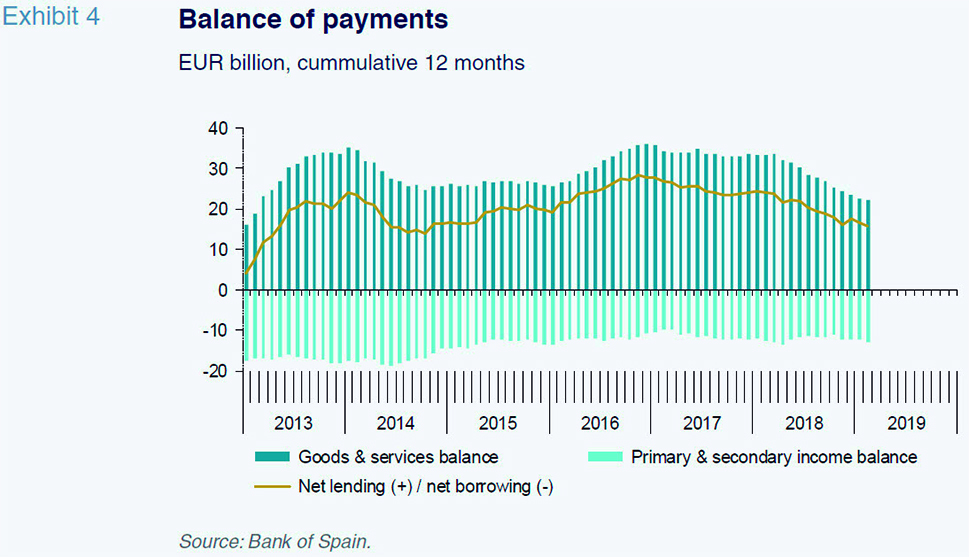

Lastly, the current account deficit to February stood at 4.2 billion euros, compared to a deficit of 2.3 billion euros in the first two months of 2018. The wider deficit is primarily attributable to the deterioration in the balance of trade, which registered a deficit during the two-month period for the first time since 2010 (Exhibit 4).

Forecasts for 2019-2021

The forecasts for 2019-2021 have assumed a slight recovery in the global economy, following the sharp downturn observed since last year. They also draw on the most recent projections issued by the leading international organisations, which assume a rebound in international trade –which would likely influence the expected improvement in economic data. Specifically, an acceleration of the Chinese economy and potential easing in trade tensions would have a particularly large impact. The expectation is that the European economy will start to emerge from the slump sustained in recent quarters. Our projections are based on the assumption that GDP growth in the eurozone will reach 1.1% in 2019, 1.3% in 2020 and 1.5% in 2021. Oil prices, which have increased due to reduced exports from Iran, are expected to remain at around current levels before embarking on a gradual decline, as other producers up their supply. It should be noted that these projections are based on oil prices of $70 per barrel of Brent, as from the second quarter.

As for fiscal policy, absent more specific information about the new government’s policy stance, the forecasts are based on both revenue and expenditure measures already approved, such as the recalibration of the Social Security tax bases and expenses relating to pensions and public sector wages pushed through before the election. The figures do not reflect the government’s proposals set down in the stability programme recently submitted to the European Union, as it has yet to be passed by the House.

Lastly, the ECB is expected to stick to its policy of quantitative easing and low interest rates throughout the projection period. This includes a new round of liquidity injections into the banking system (TLTRO III), a continuation of the policy of reinvestment in sovereign bonds and maintenance of low policy rates. We do not expect the main ECB intervention rate to return to positive territory until mid-2020, with a marginal increase to 0.33% forecast for 2021. As a result, the Spanish Treasury should continue to benefit from favourable financing conditions, so that the 10-year bond yield would marginally increase, from around 1% today to approximately 1.6% in 2021.

With these assumptions in mind, the Spanish economy is expected to continue along the soft-landing trajectory outlined in our last set of forecasts. In 2019, we estimate growth of 2.2%, up 0.1 percentage points from our last set of forecasts. The revision to our growth forecast reflects the fact that in 2018, Spanish GDP growth was also 0.1 percentage points higher than initially reported, suggesting that the pace of slowdown is unchanged (Table 1).

The slowdown in growth is the result of a loss of momentum across all of the components of domestic demand. It should be noted that the anticipated slowdown in private consumption, shaped by the current low level of household savings (under 5%), is curtailing growth in spending. Public spending, which has accelerated in recent quarters, is also expected to slow in the aftermath of this Spring’s elections. It is anticipated that investment will be the most dynamic factor, albeit losing a little pace in tandem with the other components of demand. Investment in housing, however, is not expected to lose steam until the second half of the year.

Weak growth in Spain’s trading markets will weigh on the foreign sector, which is expected to detract from growth once again in 2019. This, coupled with the increase in oil prices and the import bill, is likely to trigger a sharp reduction in the current account surplus.

These trends are expected to continue into 2020 and 2021, so our projections are for 1.8% growth for the Spanish economy during this period. However, assuming no change in import elasticity of around 1.4, the anticipated slowdown in internal demand should curtail imports. This will likely halt the deterioration of the trade balance. At these rates of growth, the Spanish economy is projected to create around 930,000 jobs, which would result in a reduction in the unemployment rate, down to 11.4% by 2021. That year, the employment rate, calculated as the ratio of the number of job holders over the working-age population, would hit a historical peak.

Growth in wages is expected to decrease in 2020 and 2021 relative to that forecast for 2019, heavily influenced by one-off factors, but should be higher than that seen in recent years. This, coupled with scant productivity gains, is similarly expected to drive higher growth in unit labour costs compared to the growth observed of late.

Lastly, the economic slowdown is likely to limit progress on reducing the public deficit, which we forecast at 2.3% of GDP in 2019, 0.3 percentage points above the government’s target. Moreover, we do not foresee that figure falling significantly over the following two years. In this context, public debt would not decline much, reaching 94.5% of GDP by the end of 2021.

Main risks

The main risks lie outside of Spain. Trade tensions between the US and China could sharpen, jeopardising the recovery foreshadowed by the main international forecasters. Elsewhere, it remains to be seen whether the German economy, particularly its automotive sector, will recover in the coming months from its weakened performance. European industry in general may have entered a more comprehensive restructuring phase than previously anticipated, a development that is not reflected in these estimates.

In Spain, an additional drop in the household savings rate or an increase in household leverage (developments not currently contemplated in these estimates) would boost growth in the short term. However, this would entail a cost in terms of financial vulnerability and the sustainability of the ongoing expansion over the medium term.

Raymond Torres and María Jesús Fernández. Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas