Downsizing, productivity and efficiency in the Spanish banking system

In response to the sharp correction in business volumes and profitability, Spanish banks have significantly pared back capacity by reducing their numbers of branches and employees. Nevertheless, closer analysis indicates that these capacity cuts have not led to an improvement in unit margin productivity or efficiency levels.

Abstract: Since 2009, Spanish banks have made a concerted effort to cut capacity through both a reduction in employees and branches, with capacity cuts far greater in intensity in Spain than in most other major eurozone economies. This has occurred over three distinct periods, with mergers, recapitalisation requirements, the need to increase efficiency, and the recalibration of banks’ distribution models providing the impetus for the banks’ restructuring efforts. This downsizing trend was also initiated to increase productivity at a time of declining business volumes. Given that the reduction in the number of branches and employees exceeded the contraction in business volumes, productivity, measured by employee and branch, has improved considerably. However, due to the combination of the volume effect and the unit margin effect, banks have experienced a significant drop in margin, thereby constraining any productivity measured in terms of the margin generated per employee and branch. Significantly, this occurred alongside an increase in per employee and branch unit costs, which has reduced banks’ efficiency. This is explained by the fact that headcount cuts have focused more on branch staff than central service staff, which exhibit higher ULCs, and the way in which banks account for the costs associated with their workforce restructuring efforts.

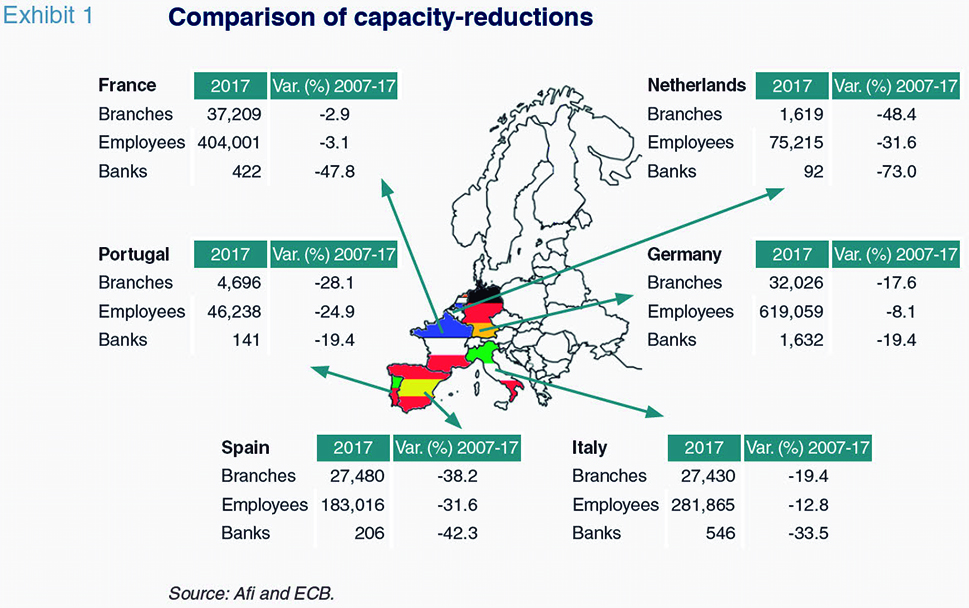

Capacity cut more intensely in Spain than in Europe

In response to the financial crisis, the Spanish banking system began to downsize, a trend which has since spread across the EU. Whether measured by the change in the number of entities, branches or employees, capacity has been cut with far greater intensity in Spain than in most other major eurozone economies.

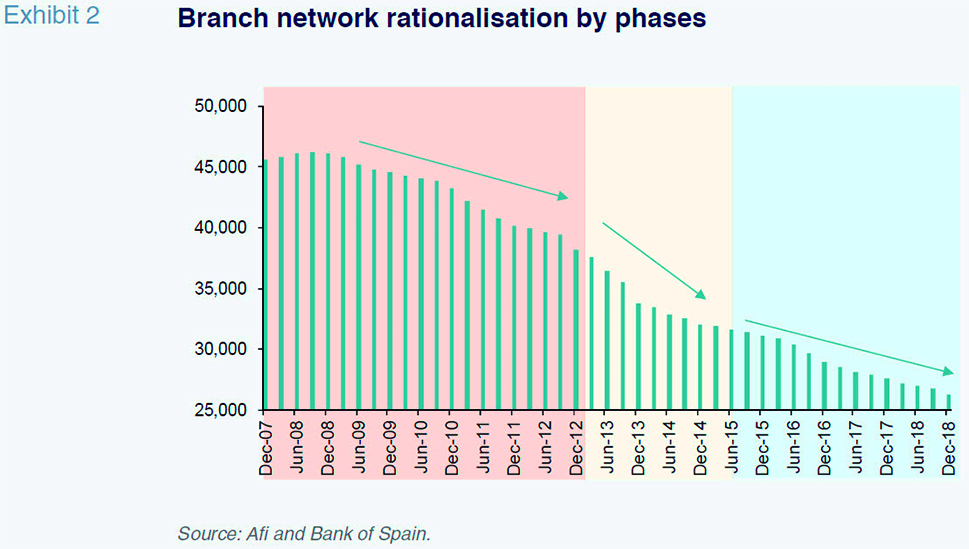

The commitment to capacity-cutting is especially evident in terms of the number of branch closures. As shown in Exhibit 2, it is possible to identify three distinct phases of this effort, each shaped by different forces.

The first phase of branch closures occurred primarily due to the numerous mergers that took place between 2009 and 2012. However, many of the merged entities had markedly different geographic footprints, presented scant overlap and, as a result, little scope for cost savings. This contributed to the relatively slow pace of branch closures.

The second phase, which lasted from 2012 to 2015, saw a marked uptick in the pace of branch closures. That acceleration was clearly driven by recapitalisation requirements outlined in the Financial Assistance Programme, which included branch closures and staff reductions. These requirements set a trend across the rest of the Spanish banking system. Healtheir banks that had avoided recapitalisation also engaged in downsizing in order to improve their relative efficiency.

The final phase began in 2015 and is the result of a much more coordinated and forward-looking strategy. It occurred alongise irreversible changes in banks’ business models due to the combination of stagnant business volumes and ultra-low rates, which meant a reduction of the added value provided by the so-called ‘liability branches’, whose main aim is to collect deposits in order to give credit in other areas where the demand is high. Additionally, bank branches faced waning customer loyalty in an increasingly competitive and digital landscape.

This shifting environment shines light on two major reasons for the restructuring of banks’ branch network: (i) the need to continuously improve efficiency at a time when banks struggle to generate income; and, (ii) the recalibration of banks’ distribution model.

Productivity in the wake of capacity cuts

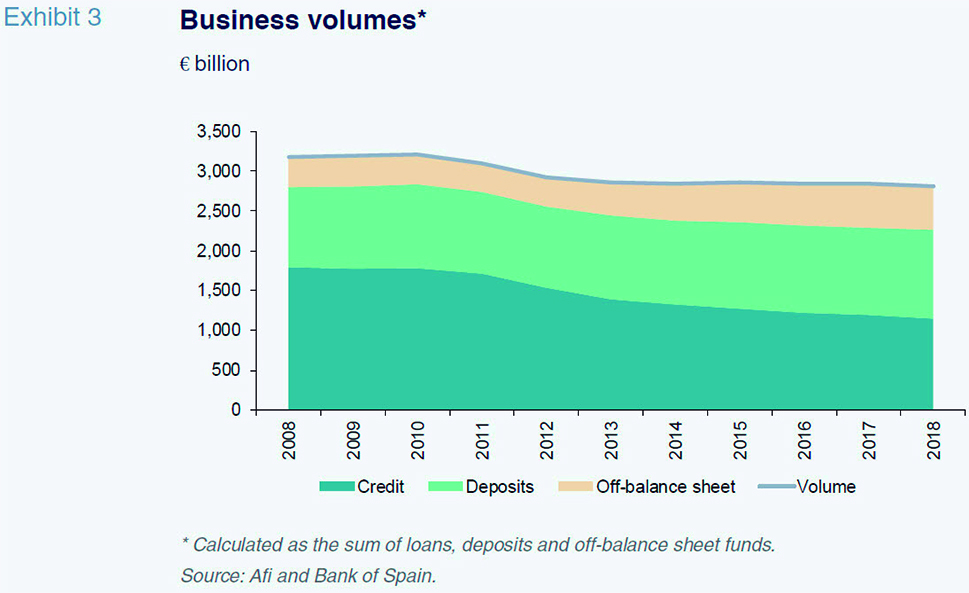

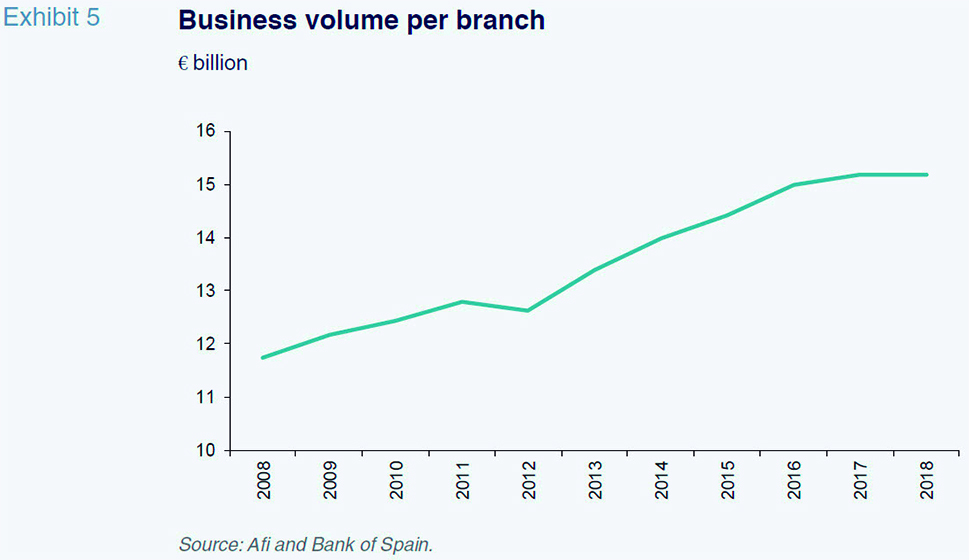

It is clear that the significant downsizing of the Spanish banking system’s capacity was sorely needed to raise productivity as business volumes, defined as the sum of lending and customer funds on and off the balance sheet, began to contract. Notably, the contraction has been far more pronounced in lending than customer funds. This trend can be largely attributed to the private sector’s (firms and households) develeraging effort, which, judging by the ongoing year-on-year contractions in lending volumes, has yet to run its course.

The stability of customer deposits as the balance of outstanding credit shrank provided Spain’s banks with liquidity buffers required as part of their financial assistance packages. Their stronger liquidity position allowed the banks to reduce the rates offered on deposits. This led to both a relative and absolute increase in off-balance sheet funds, mainly in the form of investment and pension funds.

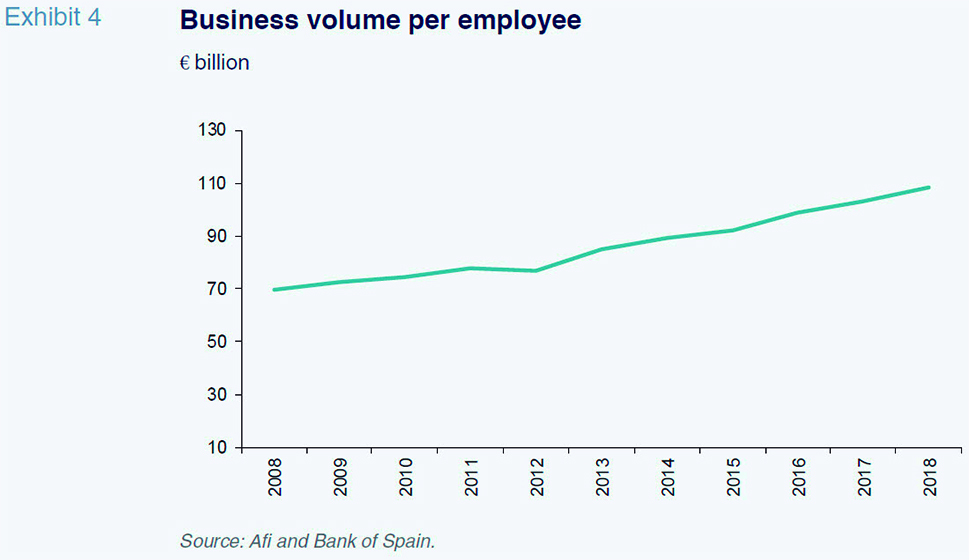

Given that the reduction in the number of branches and employees exceeded the contraction in business volumes, productivity has improved considerably, measured per employee and branch.

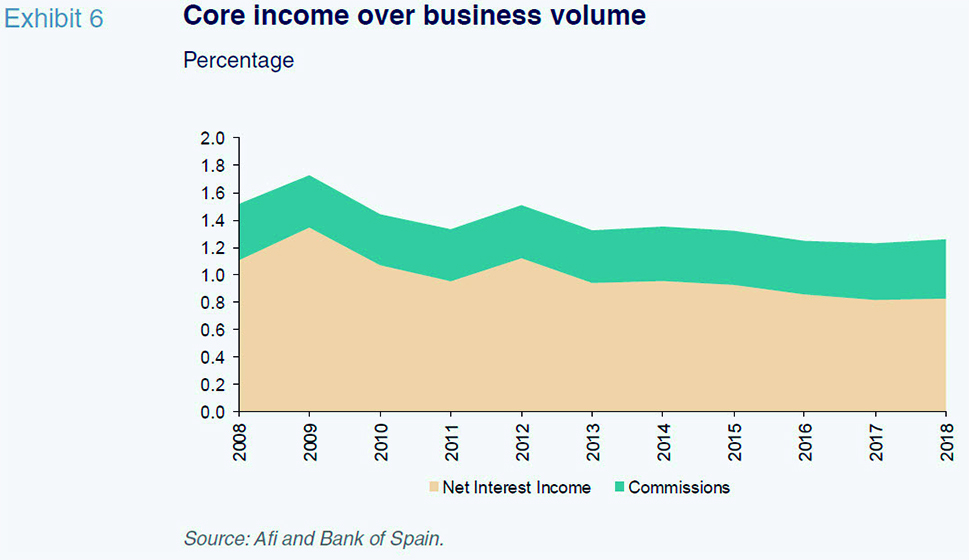

Nevertheless, a productivity measurement based solely on business volumes can be misleading. In addition to the contraction in business volumes, Spanish banks have seen their unit profitability, defined as the sum of net interest income, fees and commission income (‘core income’) over total business volumes, shrink considerably.

It is important to highlight that the improvement observed in the contribution by fees and commissions, which has been shaped above all by the growth in off-balance sheet funds under management, has not been sufficient to offset the drop in net interest income. This has occurred under pressure from the consistent downtrend in benchmark interest rates, which have lingered in negative territory for the last five years.

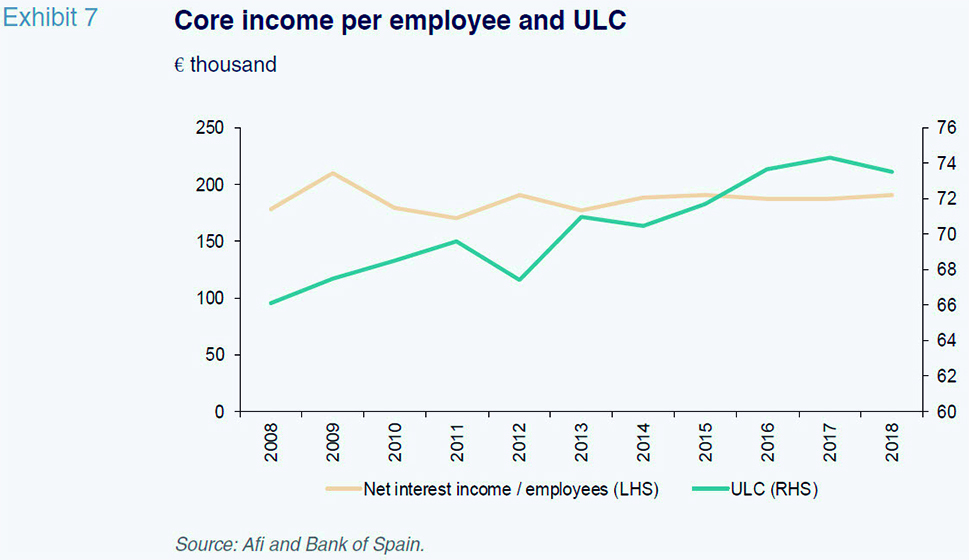

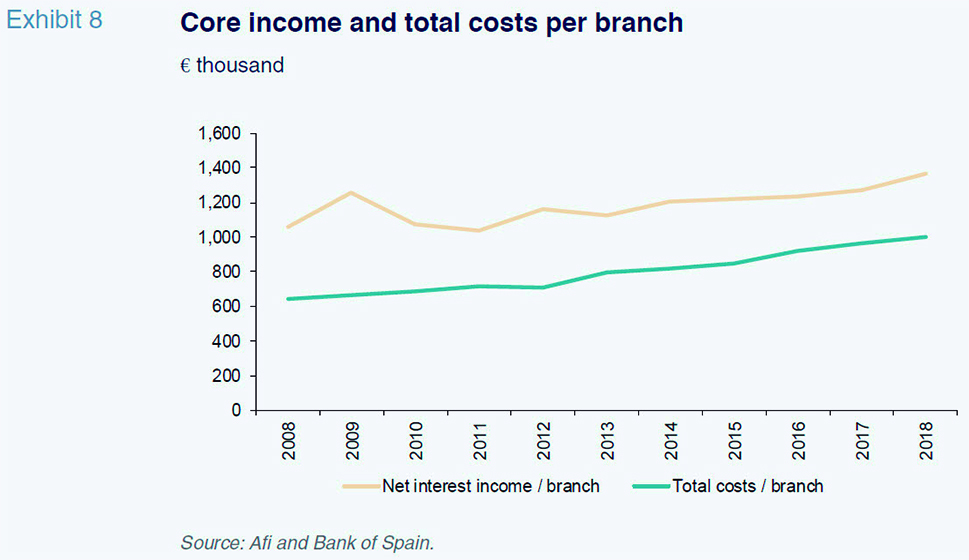

Due to the combination of the volume effect and the unit margin effect, banks have experienced a significant drop in margin. As a result, there has been minimal improvement in productivity measured in terms of the margin generated per employee and branch. This stagnation in productivity occurred along with an increase in unit costs, both per employee (unit labour costs or ULCs) and branch (total expenses per branch), which has reduced banks’ efficiency. Efficiency, or cost-to-income, measured as the ratio between total costs and core income (net interest income plus fees and commission income) has deteriorated by an increase of almost 10 percentage points.

This deterioration in efficiency is widespread across Europe. In fact, thanks to the previously discussed capacity cuts that mitigated the sharp reduction in the banks’ core income, Spanish banks have fared relatively better than many of their European peers. In those countries where capacity cuts have been less intense, the deterioration in efficiency has been more pronounced.

Recalibration of the expense structure

This comparative analysis of banks’ productivity and expenses brings us to a few additional observations about the expense dynamics in the Spanish banking system.

The first relates to the trend in unit labour costs (Exhibit 7). This metric has increased by 10% from 66,000 euros to 72,000 euros, which is virtually identical to cumulative inflation over the same period. The fact that ULCs have trended flat in real terms presents a paradox. Given that the workforce reductions achieved through early retirements and redundancy programmes have focused on older employees who generally account for higher unit labour costs, it would be expected that this metric would subsequently decrease in value. Interestingly, this decline has not occurred.

There are two possible reasons for this counterintuitive outcome. First, headcount cuts have focused more on branch employees than central service staff. The latter have experienced a heavier workload due to new regulatory requirements, analytical procedures and the collection of business intelligence. Consequently, the correlation between average employee age and ULCs is less direct than initially thought. In fact, ULCs were higher in the banks’ central services than in their branch networks for every age bracket.

The second explanation has to do with how the banks accrue and account for the costs associated with their workforce restructuring efforts, specifically the termination benefits negotiated for the employees who retired early or took advantage of redundancy programmes. Although these benefits are non-recurring, they are recognised under staff costs on the banks’ income statements. As a result, these costs have persisted, albeit rotating from one bank to the next, and are presently inflating ULCs, thereby distorting the outcomes of banks’ continual efforts to resize their workforce.

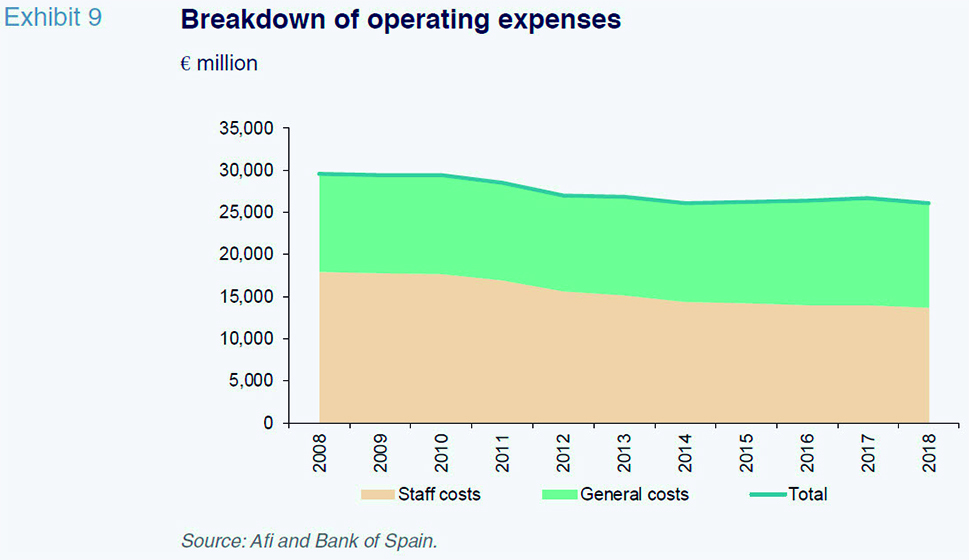

Also noteworthy is the significant recalibration of the mix between the two major expense headings of staff costs and other operating expenses. In the traditional banking model, the customer relationship is nurtured through the branches. The expense structure mirrored this situation, with staff costs accounting for almost two-thirds of total expenses.That percentage has shifted considerably, highlighting the structural transformation of the banking business towards a model where the customer relationship –and business origination in general– is far more technology driven.

Conclusion

The sharp capacity cuts observed in the Spanish banking system have mitigated the contraction in business volumes. While productivity measured in terms of business volumes has improved, productivity measured in terms of unit margins (core income per employee or branch) has not. Additionally, the capacity cuts have failed to translate into a proportionate reduction in expenses. As a result, Spanish banks’ level of efficiency has deteriorated, albeit less than other large European banking systems.

Two factors may explain this dichotomy of capacity cuts and reduction in costs. Firstly, accounting systems’ recognition of extraordinary costs associated with the workforce restructuring (e.g. termination benefits) has delayed the materialisation of the associated labour cost savings. Secondly, a significant proportion of costs are associated with banks’ traditional business models. The emerging operational shift is far more technology intensive and less dependent on physical branches.

Ángel Berges, Federica Troiano and Fernando Rojas. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S. A.