Spain’s bank-sovereign nexus (II): Perspectives from the banking sector

Although an uptick in private sector lending and the flattening of the yield curve has led Spanish banks to reduce their holdings of government bonds, policymakers are still concerned about the negative feedback loop that exists between banks and sovereign risk. However, any amendments to the treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures should be analysed in the context of the completion of a Banking Union.

Abstract: In this second article on the bank-sovereign nexus, we analyse the relationship from the perspective of the Spanish banks. The banks’ investments in fixed-income securities (particularly Spanish sovereign debt) occurred at a time when there was a steep decrease in the demand for credit amongst Spanish companies and households. These securities’ earnings, which took the form of interest income and capital gains, propped up the banks’ income statements during times of financial stress. Recently, the flattening of the yield curve, coupled with a gradual normalisation in lending activity, has prompted the banks to pare back their public debt holdings considerably, a trend that is bound to accelerate in the years to come. Nevertheless, concerns have been raised over the feedback-loop between banks and sovereign risk, sparking debate about the regulatory treatment of government bond holdings. However, we believe that if there are ultimately any amendments introduced to the regulatory treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures, these should be analysed in the context of reforms undertaken to build the Banking Union. In any event, such amendments are unlikely to be adopted anytime soon.

IntroductionThe sovereign debt held on banks’ balance sheets is the most obvious illustration of the so-called ‘bank-sovereign nexus’. This term refers to the close link between the banking system and the public sector from which both parties greatly benefit. In this article, the second in a two-part series, we will focus on the banks’ role in this relationship, having looked at the perspective of the public sector in the article published in the previous issue of the July

SEFO. [1]

The banks’ core functions require them to maintain a sizeable amount of public debt on their balance sheets. Holding liquid assets such as sovereign debt is absolutely essential for balance sheet management and compliance purposes. In addition, the banks’ key role in the payment system and the transmission of monetary policy inevitably necessitates that they hold a significant amount of public debt.

Additionally, it is worth noting that increased financial disintermediation means that banks now also act as market makers. The banks circulate new issues in the capital markets, of which public debt makes up a significant proportion.

Public debt holdings by banks: The Spanish experience

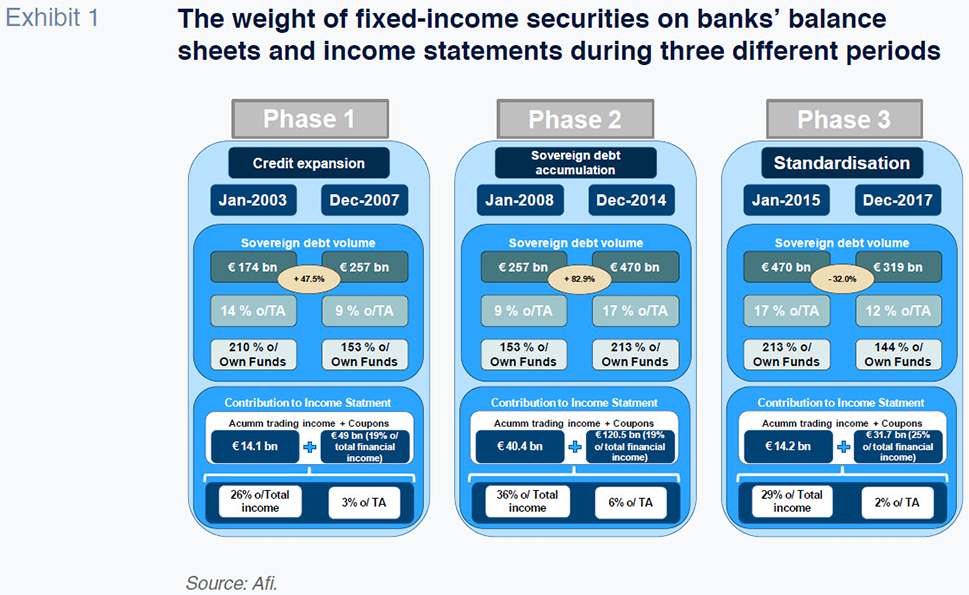

The increase in public borrowings in Spain coincided with a period of intense deleveraging in the private sector among both households and corporates. As a result, the composition of the banks’ balance sheets changed substantially: the weight of loans declined while the presence of fixed-income securities, particularly Spanish government bonds, increased. With that rebalancing the banks sought to mitigate, if only partially, the dearth of credit investment opportunities at a time of extremely weak demand for credit and sharp deleveraging by Spain’s companies and households.

By investing in public debt at a time when bond yields were rising, banks were able to improve their income statements and plug the hole resulting from a drop in profitable lending activity. These earnings took two forms. First, in the form of the interest (coupons) the banks earned on the bonds they held in their portfolios. These coupons came to represent nearly 20% of all the financial income received by the banking system between 2008 and 2014.

The second source of income proved even more important: namely, the gains made when the bonds were sold at prices higher than those at which they had been originally bought. Those gains derived primarily from the extraordinary reduction in long-term interest rates that took place in the wake of the European Central Bank president’s historical pledge in the summer of 2012 to do “whatever it takes” to keep the eurozone together. That promise had the effect of eliminating the “break up of the euro” risk factor that had penalised the sovereign bonds of several European countries, including Spain.

Once the risk premium associated with Spanish government bonds began its systematic decline, the banks accumulated significant capital gains on their public debt holdings, which could be materialised in one of two ways. The fastest route involved selling the bonds in the secondary market at prices that were substantially above their cost. The more protracted route required holding long-term bonds with a high coupon until maturity.

The Spanish banks relied on both routes to varying degrees. Exhibit 1 summarises the significant contribution made by fixed-income securities, most of which were government paper, to the banks’ earnings. The gains realised meant that the entities’ net trading income largely offset the extraordinary toxic asset provisioning effort made by the Spanish banks.

Meanwhile, the coupons earned on the banks’ government bonds in recent years have partially mitigated the adverse impact that ultra-low interest rates had on the banks’ net interest income as most of their loan books have been benchmarked to Euribor, which has been trading in negative territory for the past two years. Consequently, coupon-derived interest income represented 25% of the total finance income earned by the sector between 2014 and 2017. However, during this time, fixed-income holdings declined to 12% of total assets, a downward trend that is expected to continue in the years to come. This trend is driven by a reduced appetite for new public debt purchases due to a significant fall in sovereign debt yields. Moreover, the end of private sector deleveraging has paved the way for moderate growth in the demand for credit.

The regulatory environment and legislative proposals

Concern over the feedback-loop between banks and sovereign risk has sparked debate about the regulatory treatment of government bond holdings, particularly the fact that they are not accounted for in capital calculation or risk concentration threshold purposes.

As part of the international banking reform process, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) promised in 2015 to review the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures and make recommendations about whether and how to update that treatment. After nearly three years’ work, the Committee has acknowledged that the banks’ sovereign exposures imply risks of various kinds and magnitudes but that this exposure is essential for the banking system, financial markets and broader economy. As a result, it claims that any amendment to banking regulations requires taking a holistic approach that appropriately weighs both aspects: the risks and the rewards of the “bank-sovereign” relationship.

In taking this holistic approach to the bank-sovereign nexus, the Basel Committee concluded that there was insufficient consensus regarding what changes should be made to the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures. It therefore recommended not initiating a formal consultation process regarding such potential amendments.

Despite this, its report analysed some of the options put forward in recent years in both academic and institutional forums, which can be grouped into the following categories:

Risk-weighting framework

The main advantage attributed to sovereign exposures in terms of capital adequacy regulations is their 0% risk weight. This means they are exempted from a minimum capital requirement under the standardised approach to credit risk.

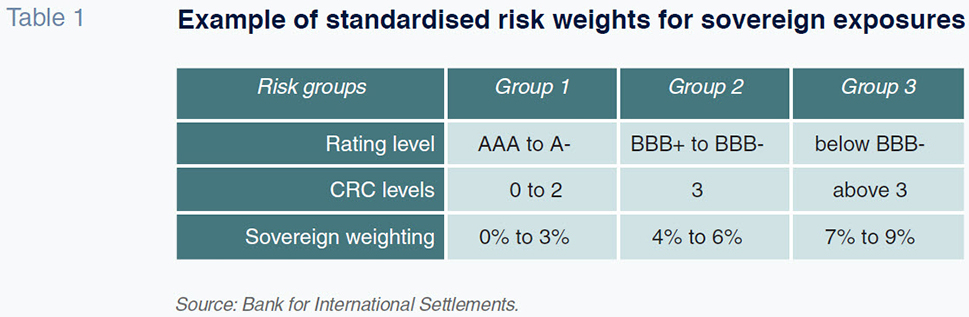

Two alternative approaches have been proposed in response. The first calls for the introduction of a risk weight that would factor in the different levels of risk posed by different sovereign issuers. The idea would be to use external ratings issued by international rating agencies or the country risk classification (CRC) established by the OECD. For the sake of simplicity, both proposals rely on a small number of categories. For example, in its analyses and simulations, the Basel Committee used groupings such as those shown in Table 1, with three risk categories and risk weights between 0% to 3% for the least risky group, 4% to 6% for the intermediate group and 7% to 9% for the highest risk group.

An even simpler approach would consist of introducing a fixed risk weight of around 2% for all sovereign exposures irrespective of the riskiness of the issuer. Regardless of the route taken, the immediate implication would be a substantial increase in the banks’ capital requirements.

Large exposures framework

Another advantage associated with banks’ sovereign exposures is the exemption from the large exposures framework. Large exposures, defined as those that exceed 10% of eligible capital (tier 1 capital), cannot exceed 25% of such capital, a threshold that falls to 15% in the case of global systemically important banks (G-SIBs).

The second category of proposals for changing the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures consists of the elimination of that exemption, in full or in part, imposing a somewhat higher limit than that currently in place for exposures to non-sovereign entities, e.g., 100% of capital for sovereign exposures versus 25% for the rest. This proposed regulatory amendment would not impact the banks’ capital requirements. However, it would force them to sell public debt securities in the amount needed to comply with the thresholds applicable in proportion to their capital, thereby exerting downward pressure on the price of these securities (and upward pressure on their yields).

Hybrid approach

A third alternative consists of a hybrid of the first two proposals. Under this approach, banks wouldn’t be required to set aside capital for small sovereign exposures; however, the capital requirement would be significant when such holdings exceed the threshold proposed by the large exposures framework. The hybrid approach seeks to eliminate: (i) the immediate impact that a stringent limit would have on sales; and, (ii) a risk weight for reduced holdings of own-country sovereign debt.

The hypotheses modelled by the Basel Committee contemplate marginal risk weight add-ons as a function of the percentage of sovereign exposures over own-funds (CET1) as follows:

Pillar II

In addition to those proposals based on quantitative metrics, there are a number of proposals that rely on more qualitative measures, namely Pillar II and Pillar III requirements. Pillar II guidance refers to the ongoing supervisory review process under which there is scope for introducing additional capital requirements. The idea would be to include sovereign exposures in the supervisory review process, requiring the banks to compile and monitor risk indicators specifically associated with their sovereign exposures. They would also have to regularly stress test their sovereign exposures in order to quantify their maximum exposure and identify corrective measures when such exposures exceed acceptable limits.

Pillar III

The last group of proposals focus on the banks’ Pillar III disclosure and transparency requirements in a bid to effectively strengthen market discipline. This would entail increasing the level of detail of the sovereign exposure disclosures provided to the market. Specifically, these disclosures would be broken down by issuer type, issue term and both currency and accounting classification.

In the case of both Pillar II and Pillar III, there would be no immediate impact in terms of exposure limits and/or additional capital requirements, although these could materialise indirectly as part of the supervisory review and evaluation process (SREP).

Spanish banks and potential changes to the regulatory treatment of sovereign debt

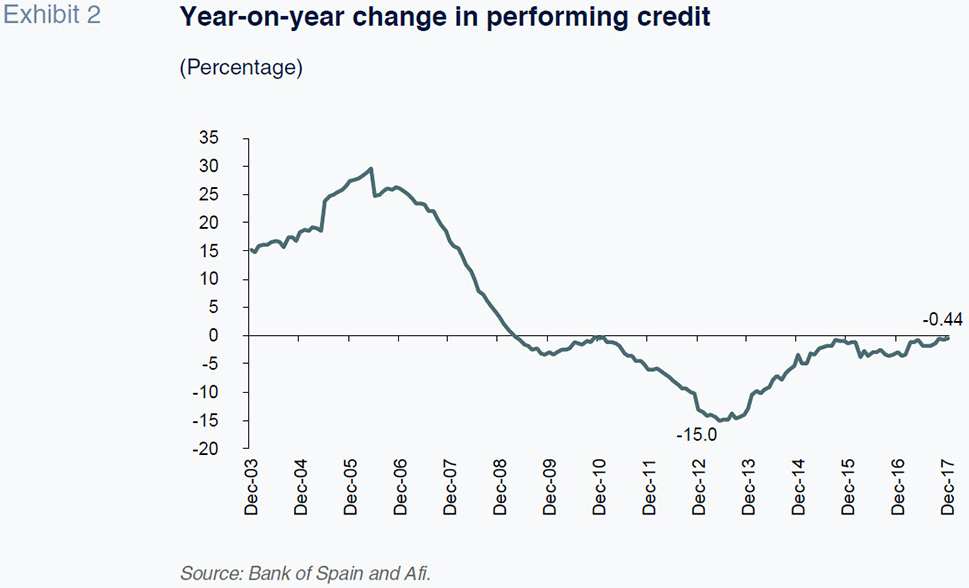

There are several reasons to believe that Spanish banks will reduce their sovereign exposures sharply in the years to come even if the regulatory framework remains unchanged. Firstly, as shown in Exhibit 2, demand for credit appears to have recovered after five years of deleveraging by companies and households. This uptick in demand represents an investment opportunity that the banks are unlikely to ignore.

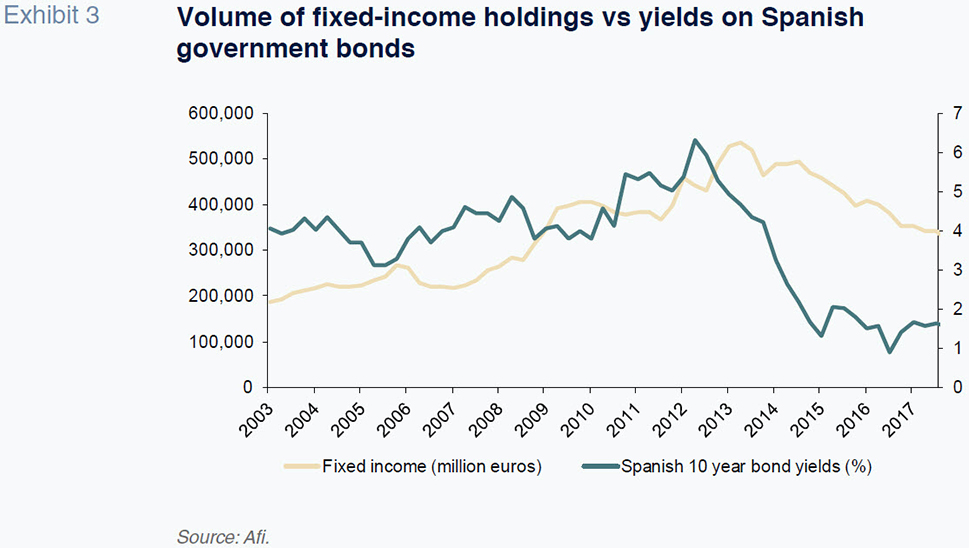

Coupled with the growth in demand for credit, the appeal of investing in sovereign debt has diminished considerably. Yields have fallen sharply at the long end of the curve, reducing the benefits of the carry trade strategy that, for several years, constituted the greatest incentive for holding public debt. As illustrated in Exhibit 3, banks have reacted to the drop in long-term rates by significantly reducing their sovereign debt holdings.

Not only have they reduced their holdings, but the underlying investment strategy suggests a growing fear of possible rate hikes that could trigger capital losses and harm their earnings.

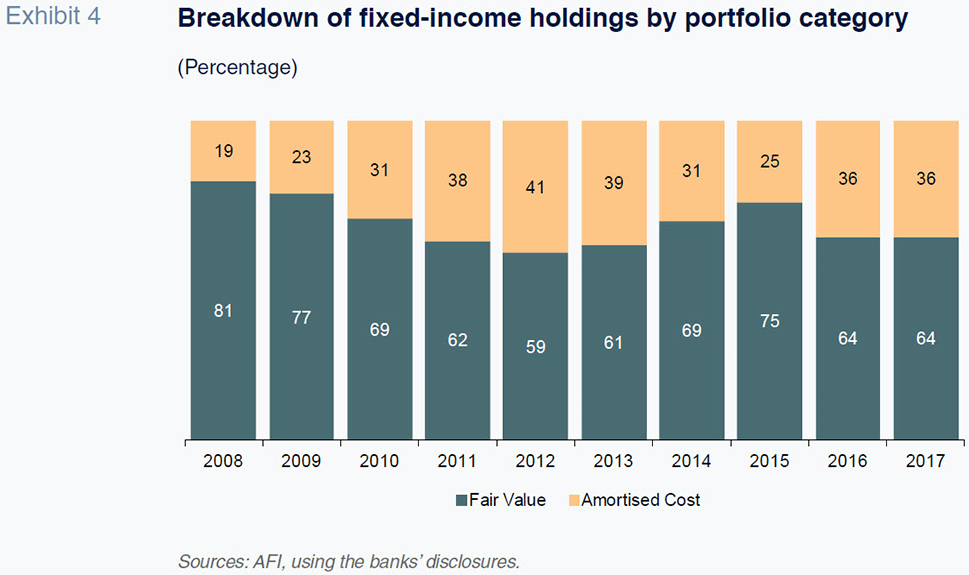

This becomes apparent if we analyse the breakdown by two major accounting portfolio categories: (i) the securities that are measured at fair value for accounting purposes (the “held for trading” and “available for sale” portfolios); and, (ii) those measured at amortised cost (“held to maturity”). In the last two years, during which time long-term rates have been at their lowest and concern over a possible uptick has been rising, we have seen a clear shift away from fair value towards amortized cost portfolios (Exhibit 4).

The combination of the renewed demand for credit and the reduced appeal of sovereign debt as an investment suggests that the weight of sovereign exposures on the banks’ balance sheets will fall sharply in the coming years, particularly as the numerous bonds purchased (measured at amortized cost) mature without reinvestment.

Despite this anticipated decline in sovereign bond exposures, we have nevertheless attempted to simulate the potential impact of the regulatory changes outlined in the previous section on the Spanish banks. We used the latest available sovereign debt figures (year-end 2017) and assumed that the changes would be introduced with immediate effect. Given these assumptions, it is clear that the estimated impact should be viewed as an extreme case that is highly unlikely to materialise.

The first part of our analysis models the introduction of sovereign risk weights in line with those outlined in Table 1, i.e., weights applied to every euro invested. We performed the analysis on 12 banks that together represent approximately 90% of the banking sector’s total assets.

As shown in Table 1, and performing an exercise of maximums, the banks’ risk-weighted assets (RWA) would increase as a result of the application of a risk weight of 3% on all Spanish public debt holdings due to the A- rating, and of 4.5% on all foreign public debt holdings, because the foreign debt holdings are from peripheral countries, essentially Italy and Portugal, and we estimate that 4.5% average weight. In this scenario, the banks’ additional capital requirement would amount to around 1.8 billion euros and the adverse impact on their CET 1 capital would range from 5 to 28 basis points.

In the second scenario, we assume a limit on public debt holdings of 100% of equity. This policy would initiate a sell-off of public debt by those entities whose sovereign exposures exceed 100% of equity. We estimate that aggregate sales would amount to approximately 86 billion euros.

For our last scenario, we assume a hybrid of the first two, i.e. the application of a weight factor to fixed-income holdings in excess of 100% of equity, using the figures outlined in Table 2. Assuming that the banks continue to hold debt securities, the overall impact would be a reduction in their capital ratio (CET 1) of between 0 and 86 basis points. However, this impact would be considerably lower if the banks were to dispose of securities in order to get closer to the threshold at which capital requirements are activated.

Final thoughts in light of Banking Union reforms

Our analysis demonstrates that Spanish banks are decreasing their exposure to sovereign debt in response to the asset’s reduced appeal as an investment and the growing demand for credit. As a result, the potential introduction of capital requirements and/or quantitative limits on those holdings would have a limited impact on the banks; indeed, if the implementation timeline were sufficiently staggered, the impact would be practically nil.

Regardless of this limited impact, the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures needs to be analysed in the context of the completion of the Banking Union, which should be tackled as a whole and not on a piecemeal basis.

One of those pieces involves the creation of a eurozone-wide ‘safe asset’. In order to examine how such a step could be taken, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) set up a High-Level Task Force on Safe Assets, which recently published its conclusions.

In its report, the Board calls for the creation of a synthetic security comprised of a basket of sovereign bonds issued by eurozone members and weighted based on participating states’ contributions to the ECB capital key. There would be a junior layer that would absorb any initial losses so that the remaining senior tranche would remain risk free (equivalent to a AAA rating).

The introduction of this new synthetic security, which would constitute a eurozone ‘safe asset’, is a fundamental and complementary component of the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures. Specifically, the Taskforce concluded there would be insufficient demand for these new synthetic securities (called sovereign bond-backed securities or SBBS) unless regulators treated them as equivalent to sovereign exposures. For this reason, the Taskforce proposed that either SBBS be afforded the same favourable treatment as sovereign exposures or such favourable treatment should be eliminated.

Although the launch of SBBS and regulatory treatment of sovereign debt are important, it is clear that completion of the Banking Union requires far more ambitious endeavours. Despite the desirability of a complete and all-encompassing Banking Union, the acknowledgement that this is not feasible in

the short-term has led to the proposal of more realistic policies such as those contained in the recent position paper by the Bruegel Institute (Schnabel-Véron, 2018). This paper outlines the main theses contained in the CEPR Benassy-Quere et al., report, which was written by a group of French and German economists (Benassy-Quere et al., 2018). Their pragmatic position is that the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures should be an integral part of the reforms undertaken to build the Banking Union, in parallel with three other initiatives:

- The launch of a ‘safe asset’ using the above-mentioned synthetic formula and a regulatory treatment similar to that currently afforded to domestic sovereign debt holdings.

- The effective implementation of a European deposit insurance scheme that would provide consistent guarantees across the entire Banking Union. However, contributions made by each bank could vary depending on states’ differentiated risk profiles.

- The elimination of existing restrictions on the pooled management of solvency and liquidity at banks with subsidiaries in different European countries insofar as those restrictions impede cross-border bank concentration.

Only in the context of such far-reaching reforms would the introduction of sovereign exposure capital requirements and/or concentration limits be acceptable for the Spanish banking system. At any rate, the possible transition periods for undertaking the reforms would also need to respect the initiative’s underlying holistic and interconnected spirit. Specifically, the implementation timeframe (“phased in”) for potential sovereign exposure capital requirements and/or limits should include the introduction of a Eurozone safe asset and pan-European deposit insurance scheme.

Notes

References

BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS (2017), The regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures - discussion paper.

BENASSY-QUERE, A.; BRUNNERMEIER, M.; ENDERLEIN, H.; FARHI, E.; FRATZSCHER, M.; FUEST, C., and I. SCHNABEL (2018), Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: a constructive approach to euro area reform. Center for Economic Policy Research Policy Insight No. 91.

EUROPEAN SYSTEMIC RISK BOARD (2015), Report on the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures.

EUROPEAN SYSTEMIC RISK BOARD, (HIGH LEVEL TASK FORCE ON SAFE ASSETS) (2018), Sovereign bond-backed securities: a feasibility study, January 2018.

SCHNABEL, I., and N. VERON (2018), Completing Europe´s Banking Union means breaking the bank-sovereign vicious circle. VOX CEPR’s Policy Portal, 16 May 2018.

Ángel Berges, Alfonso Pelayo and Fernando Rojas. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.