European fiscal policy: Situation and reform prospects

The creation of a single currency and subsequent loss of national monetary sovereignty means that eurozone countries must rely mainly on fiscal policy to fight recessions and avert the excesses often associated with expansionary periods. However, in some instances, existing European coordination rules may exacerbate business-cycle imbalances, rather than correct them, sparking the debate over the kind of reforms that can provide the eurozone with effective counter-cyclical policy instruments.

Abstract: The creation of a monetary union by definition entails the loss of national monetary sovereignty. As a result, eurozone member states have to rely on budgetary tools in order to tackle macroeconomic shocks. In practice, however, these countries face serious constraints in implementing counter-cyclical fiscal policies at the national level. This is due, firstly, to the fiscal rules undertaken in response to the financial crisis. Indeed, under the current coordination system, fiscal policies tend to be pro-cyclical, which exacerbates business-cycle imbalances, limits growth potential and hinders the scope for debt relief. Secondly, Europe lacks the kind of supra-national instruments which would help counteract the inability of national fiscal policy to mitigate shocks. This conundrum has spurred a debate over potential eurozone reforms that could include: i) changes in the rules that coordinate national fiscal policies; and, ii) stronger European-wide fiscal instruments, such as an EU-level investment fund or unemployment benefit, a “rainy-day”, fund or the creation of a eurozone treasury capable of enacting counter-cyclical policies similar to those seen in the United States.

[1]

Introduction

Ever since the creation of a single currency, eurozone governments’ ability to exert economic influence and counter financial shocks mainly relies on budgetary tools. Fiscal policy has therefore become the mainstay of macroeconomic management for these countries.

In theory, fiscal policy can ease the effects of a recession and pave the way for consolidation once the economy begins to expand. However, in practice, fiscal policy has failed to play the counter-cyclical role that was expected.

[2]

Since the onset of the sovereign debt crisis in 2010, the European Union has enhanced fiscal policy rules and coordination procedures, especially within the eurozone. This process has been characterized by the EU’s effort to contain fiscal deficits through closer surveillance of member states’ public finances. The tightening of the Stability and Growth Pact (particularly after adoption of the “fiscal compact”) represents the cornerstone of this policy (Begg, 2018).

More recently, the debate has centred around the possibility to widen the range of European fiscal policy instruments. Thus, supranational measures are now being considered, such as the creation of a European instrument for counter-cyclical management and a follow-up mechanism that takes into consideration the fiscal position of the EU as a whole. But these are merely ideas and projects that have yet to be translated into concrete actions.

This article aims to analyse the current situation and future prospects of European fiscal policy. First, existing mechanisms are reviewed from the perspective of both cross-country coordination and available European-wide tools. Secondly, the impact of existing mechanisms on budgetary imbalances, growth and employment is examined. Although the findings are primarily based on qualitative analysis, they also take into consideration key trends and the results of several quantitative studies. The article concludes with an overview of possible fiscal policy reforms.

Coordination of national fiscal policiesThe EU’s current fiscal policies coordination procedure is based on decisions adopted in 2011 when the sovereign debt crisis was in full swing. The financial crisis that led to Lehman Brothers’ collapse in 2008 had a dramatic impact across both developed and emerging economies. In response, European countries joined the global effort to combat recessionary pressures by means of fiscal stimulus measures. For example, the G20 agreed to provide coordinated fiscal support that amounted to around 2% of global GDP.

[3] This increase in government spending resulted in a widening of public deficits and higher public debt.

The first “green shoots” of recovery appeared at the beginning of 2010, including in Spain. Consequently, that year, the European Commission changed its policy position and advocated instead a tighter fiscal stance. In retrospect, it is clear that the European Union underestimated both the risks of financial fragmentation inherent to the eurozone and the economic impact of a restrictive macroeconomic policy. It is during this period that the EU designed its current system of coordination of national fiscal policies.

How does the present fiscal policies coordination system operate?

European coordination of national fiscal policies consists of a complex set of rules, recommendations and codes of conduct (Wieser, 2018).

In 2011, the Stability and Growth Pact was strengthened (Regulation 1173/2011) through the adoption of preventive actions in order to forestall excessive public deficits. This decision reflects an acknowledgement of the interconnection of economies belonging to the economic and monetary union, thereby necessitating macroeconomic surveillance under the guidance of the European Commission (Article 121 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union).

This preventive surveillance mechanism consists of three key parts: i) a deficit target adjusted for the business cycle of no more than 1% of GDP in order to meet the medium-term objective of achieving a structural balance in public finances;

[4] ii) member states’ annual submission of a stability program to the European Council and Commission outlining medium-term objectives and their underlying assumptions; and, iii) the Council’s opinion including its recommendations which are then incorporated into the European Semester. If the Council’s recommendations are not adopted, a country can face sanctions of up to 0.2% of GDP.

In addition to these preventive measures, the Stability and Growth Pact also states that a country which consistently deviates from the balanced budget goal can be subject to

corrective measures. Under such circumstances, the Council is authorized to make decisions regardless of the vote cast by that member state. This corrective leg of the Pact is known as the

Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP). In essence, the EDP is activated when fiscal imbalances do not meet certain criteria (

i.e., a 3% of GDP deficit limit).

[5]

Determining member states’ compliance with these criteria lies with the Council, which bases its decision on a report issued by the Commission. The Council can request that a member state adopt corrective measures within a time span of less than 6 months. In cases of repeated non-compliance, the Council can enact sanctions of up to 0.5% of the GDP of the country concerned. If the member state has hindered the follow-up mechanism or manipulated statistics, additional sanctions may be imposed.

Finally, the Fiscal Compact, which came into force in 2013, includes a “golden rule”, whereby a member state’s public deficit cannot exceed 0.5% of GDP over the business cycle (1% for low-debt countries). The golden rule is binding for all countries that have ratified the Pact (i.e., all EU member states, except Croatia, the United Kingdom and the Czech Republic). Importantly, each member state must incorporate the golden rule into a law.

In the case of Spain, the principle of fiscal stability is contained in Article 135 of the Constitution. Legislation also provides for an “expenditure rule”, limiting the increase of non-financial spending to nominal GDP growth over an entire business cycle.

In principle, a member state can appeal to the European Union Court of Justice if it believes another member state has contravened the golden rule. Additionally, financial support granted by the European Stability Mechanism is reserved solely for countries that have ratified the Fiscal Compact.

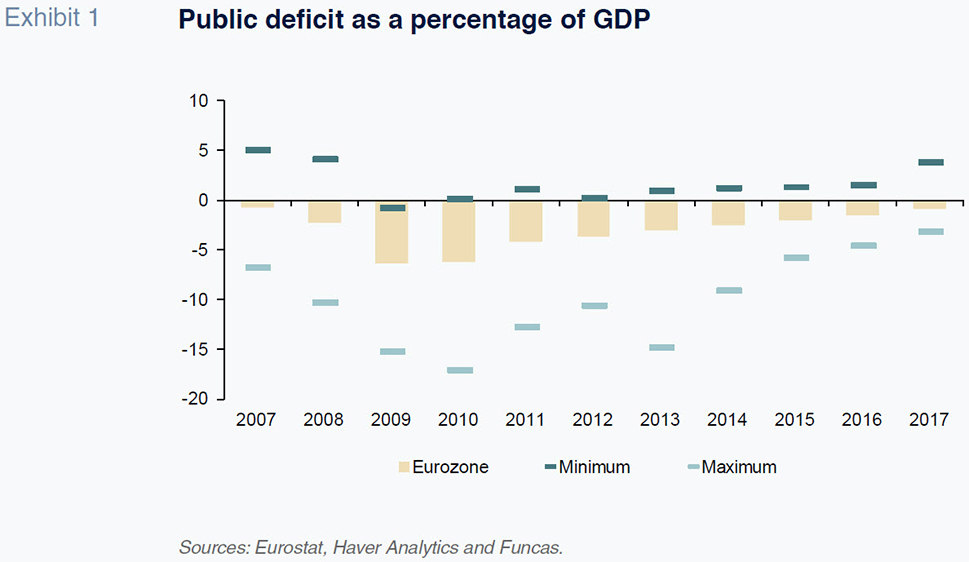

What has been the impact of the present fiscal policies coordination system?The EU began to tighten fiscal policy rules as the financial crisis intensified but their actions became particularly aggressive following the adoption of the above-mentioned 2011 regulations and 2013 Fiscal Compact. These policies effectively contributed to a downward trend in public deficits across the EU (Exhibit 1). Obviously, the reduction in interest rates due to the ECB’s shift in monetary policy in 2012 also played a role. However, the primary deficit, which excludes interest payments and is therefore less affected by ECB policy, has also decreased.

In addition, the public debate is increasingly aware of the importance of balanced budgets. For example, in many countries, European mechanisms have triggered a dialogue among governments, social partners, the European Commission and scholarly experts.

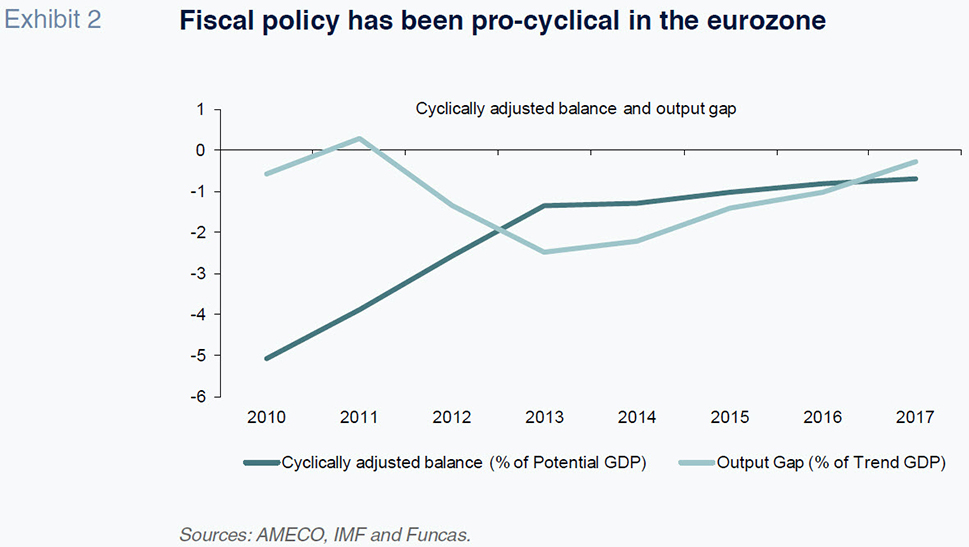

However, fiscal coordination faces major challenges. The main one is the pro-cyclical nature of adjustments resulting from present coordination rules (Exhibit 2). This is a key issue, indeed a pro-cyclical fiscal policy –besides wasting the only macroeconomic management tool available for the eurozone countries– tends to aggravate the impact of recessions on growth and unemployment. Some authors have identified a negative impact of pro-cyclical fiscal policy on the European economy, in terms of both aggravating the depth of recessions and reducing long-term growth (Fatás and Summers, 2017).

It is a fact that fiscal policy has been tightened during the downturn phase caused by the debt crisis (Bénassy-Quéré

et al., 2018). During the hardest years (2011-2013), virtually all countries adopted austerity measures. Hence the structural deficit reduction of 2 percentage points –whereas fiscal policy support is to be expected in times of cyclical economic downturn. The impact was particularly acute in those countries most affected by the credit crunch.

[6]

Furthermore, in contrast with what would be desirable, recovery is characterized by a loosening of consolidation efforts. The fact that the deficit experienced a strong contraction in the 2010-2012 period in all eurozone countries (in Spain, the reduction period was somewhat longer) is significant. During that period, eurozone GDP went from a 2.1% increase in 2010 to a 0.9% decrease in 2012 (a slowdown of 3 percentage points).

On the other hand, the fiscal consolidation process has slowed down during the ongoing expansionary period. In most member states, the structural deficit has hardly undergone any change, and it may have even increased, as in Spain. This partially owes to the need for reversing some of the restrictions applied during the recession period –expenditure reduction or tax increases.

Meanwhile, the main European countries not participating in the single currency either increased their deficit (Denmark and Sweden) or kept it at the same level (United Kingdom) during the 2010-2012 period. On the contrary, fiscal policy has been generally restrictive since recovery began in those countries. Today, Denmark and Sweden enjoy a comfortable surplus and the United Kingdom has reduced its deficit.

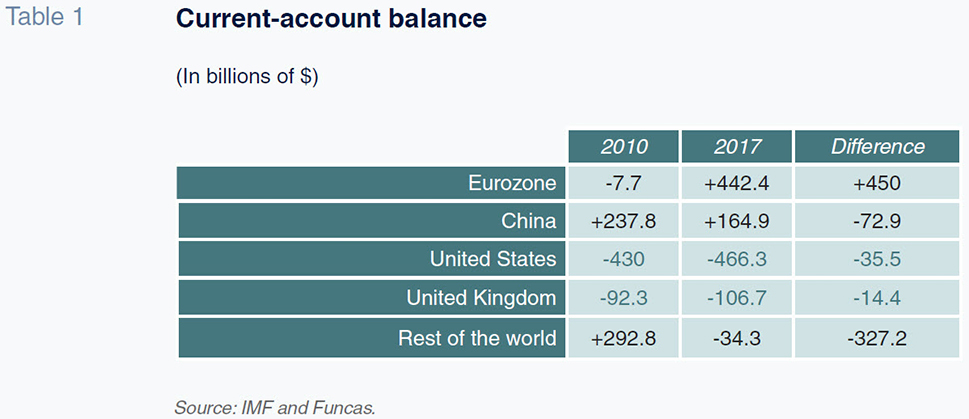

The second problem of the coordination system lies with the asymmetric treatment of deficit versus surplus countries (Bofinger, 2018). European institutions are relatively demanding towards countries requiring fiscal adjustment, while they are more benevolent in surplus situations. As a result, fiscal policy tends to be globally contractive, especially in periods of recession.

This deflationary bias, which reflects the measures adopted during the sovereign debt crisis, may have contributed to the sharp increase in the eurozone’s current account surplus (Table 1). In 2017, the surplus amounted to almost 400 billion euros, the highest level since the creation of the single currency. That is to say, the Eurozone is characterized by insufficient investment, in relation to available savings. Imbalances are the highest among leading world economies, representing a source of global concern –besides fueling the protectionist discourse outside Europe.

European Semester recommendations also tend to be asymmetric as they are more coercive regarding public expenditure than tax measures. This is a relevant issue as adjustments by means of expenditure cuts during a recession tend to have a greater effect on the economy than tax increases. This is particularly true for high-income taxpayers whose consumption levels are more difficult to influence (Berger et al., 2018).

The relatively successful experiences of countries like Portugal or Sweden, which have adopted a combination of expenditure constraints and tax increases, show that there is more than one way to reduce a fiscal deficit.

As a result of the risks associated with such asymmetries, the European Semester now relies on a new methodology, which emphasizes evaluation as a tool to improve expenditure and tax efficiency, thereby reducing the need for spending cuts. This approach also encourages the creation of independent fiscal authorities –such as the Airef in Spain– tasked with considering a wide variety of corrective options. The idea is that each country should consider the path which fits best with its particular priorities and collective choices.

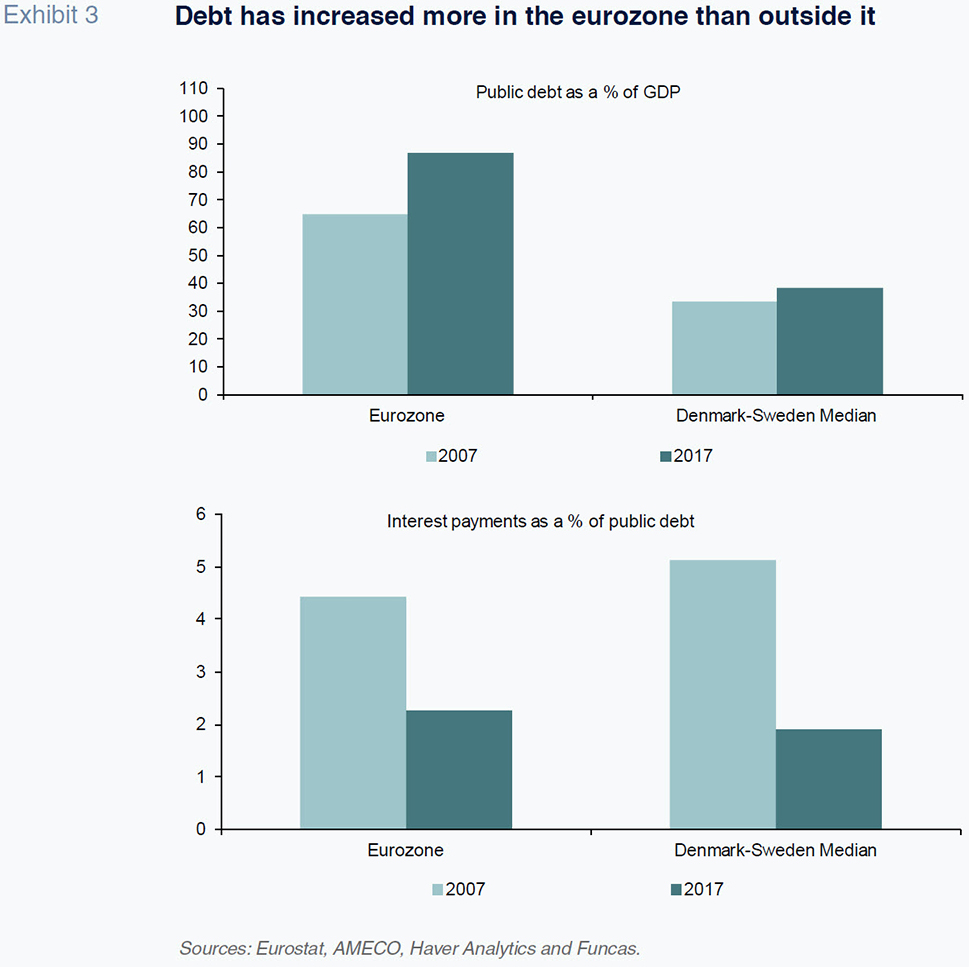

Third, the current system has so far had a mixed impact on the long-term prospects for public debt, having de facto functioned as a short-term deficit device.

[7] True, the present environment of moderate growth and low inflation has not favoured debt reduction (Exhibit 3). Moreover, states have been compelled to assume liabilities from the private sector, such as those associated with losses in the financial sector. However, the rising debt levels have attracted little attention as part of the coordination system. A medium-term strategy for tackling debt, while supporting growth and job creation is missing.

Moreover, greater consideration should be given to the fact that public debt may reflect different realities. In some cases, countries get indebted in order to fund investment and growth-enhancing policies, thus fostering potential growth and facilitating debt reduction in the medium term. Examples include increasing technological capital or improving a country’s infrastructure. By contrast, in other cases, governments have resorted to debt in order to meet current consumption and transfers. Financial burdens associated with such debt will be difficult to carry, especially when interest rates increase.

Supranational fiscal policy tools

Besides the ability to coordinate fiscal policy across countries, the EU can also influence macroeconomic developments directly through its own budget tools. This includes structural funds and the investment initiative known as the “Juncker Plan”.

However, available fiscal capacity is limited, especially when compared with large federal states like the United States. In particular, the tools are not up to the task of confronting asymmetric shocks. The reunification of Germany or the bursting of the real estate bubble in Spain are examples of the sort of shocks that required a specifically tailored macroeconomic response. In the past, the exchange rate could act as a key adjustment mechanism in such situations. However, by definition, this option is not possible in the Eurozone under a single currency regime.

In addition, having renounced to the monetary tool in favor of the ECB, which, by nature, cannot discriminate among member states, the only room for maneuver left is to be found in fiscal policy. And, fiscal policy is conditioned by the criteria established in the Stability and Growth Pact, which in practice limit its responsiveness to asymmetric shocks.

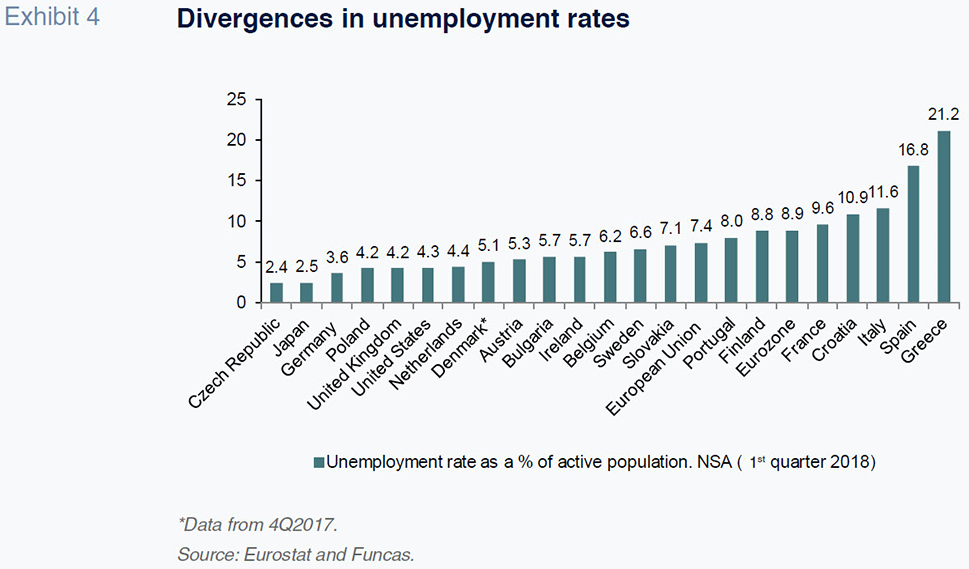

European instruments have also had limited success in achieving cross-country convergence within the Eurozone. The convergence process has in fact slowed in recent years, as illustrated by the marked unemployment differentials that presently exist (Exhibit 4).

A comparison of productivity and investment rates leads to similar conclusions. This analysis highlights the need to capitalise on new technologies, notably the incipient artificial intelligence revolution. R&D, patents and robotics indicators also point to a divergent scenario, which pose a challenge to European integration.

Lastly, the creation of the eurozone coincided with a lack of monetary support for member states to overcome insolvency crises –the so-called “original sin” of the euro (Bofinger, 2018). In countries outside the eurozone (and of course in the US), the public treasury is backed up by the central bank which is empowered to confront financial crises. These occur, for instance, when capital flows face “sudden stops” or other reasons unrelated to the sustainability of public finances.

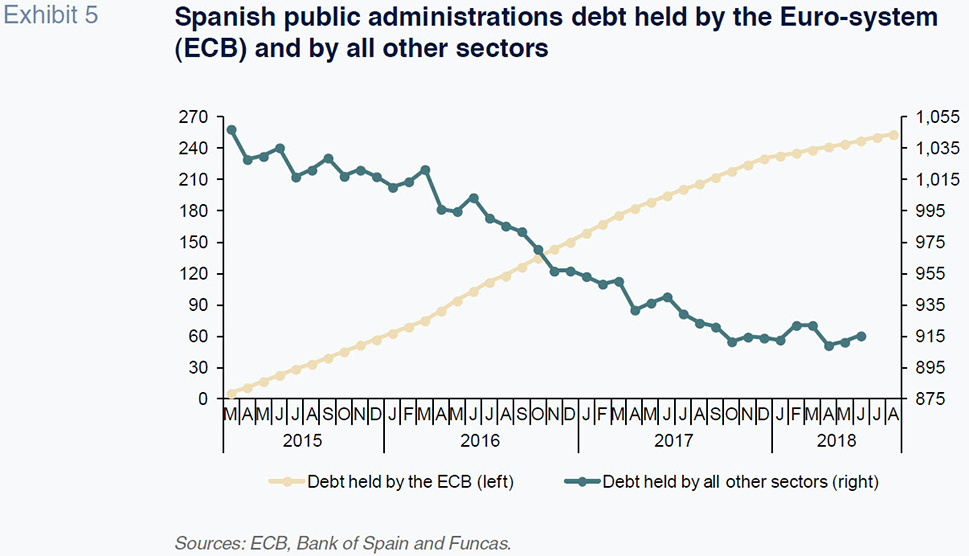

The sovereign debt crisis in 2010 was caused by such an episode of sudden stops. Thanks to ECB intervention, and especially to the public debt securities purchase programme, the risk has receded, though not completely disappearing. Thus, normalization of ECB monetary policy poses a serious challenge, particularly for highly indebted countries such as Spain, all the more since nearly 20% of their debt is placed in the Euro-system (Exhibit 5).

In order to avoid new financial crises, it is crucial to complete the eurozone’s banking union, which would reduce the exposure of bank balances to national public debt. Furthermore, a mechanism is needed to confront solvency crises that occur when a state is unable to assume its debt burden. To that end, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was created. However, the rule of unanimity and consultation of all national parliaments represents a major hindrance in this respect. Some analysts therefore advocate for a transformation of the ESM into a European monetary fund with decision-making capacity dependent on a qualified majority.

Reform options

The reform debate currently pivots around two main issues: i) the establishment of mechanisms intended to reinforce cross-country coordination, including the possibility of simplifying the Stability Pact, harmonizing tax bases and fighting tax evasion; and, ii) the establishment of fiscal mechanisms at the European level, such as European investment protection and unemployment insurance/reinsurance strategies, a fund for extraordinary contingencies (i.e., a “rainy-day” fund) or even more ambitious proposals implying the creation of a Eurozone Treasury capable of developing a counter-cyclical fiscal policy.

Improving coordination of national fiscal policies

The European Union, aware of the risks associated with stagnation in the completion of the economic and monetary union, has begun to correct the system (Buti et al., 2018), but the efforts made must coincide with more substantial reforms.

First, a credible strategy for medium-term debt reduction is needed. By focusing mainly on short-term deficit reduction, the impact of adjustment measures on future growth, tax bases and future deficits is not taken into consideration.

A different way of redefining objectives would be to include assets generated by public administrations. Investments in new technologies and other intangible assets, financed though short-term deficits, foster productive potential and the ability to increase tax collection in the future. The same can be said of public investment in infrastructure. In certain countries, such as Italy, deficit containment has been achieved at the expense of the country’s infrastructure, education system and scientific capital. A thorough formulation of fiscal objectives would consider alternative budgetary choices.

Secondly, fiscal policy must take the business cycle into account, and avoid expenditure cuts and tax increases during recessionary periods. As noted above, a pro-cyclical trend of reducing imbalances is counter-productive from the business-cycle point of view, as it unnecessarily harms job creation and weakens growth potential. Moreover, it impedes the fulfilment of debt objectives. A counter-cyclical logic also implies that criteria should be more resolutely met in times of expansion.

Thirdly, it is advisable to prioritize institutional development over a close European follow-up of national fiscal policies, which is perceived as excessively intrusive vis-à-vis country preferences. It is indeed crucial that procedures conform with democratic institutions, which are ultimately responsible for the decision-making process and reflect the specific situation of each country.

To that end, the creation of independent fiscal institutions at the national level, or the strengthening of those already existing, would be helpful. Such institutions could become an important link within the European coordination system. Tax and expenditure policies evaluation is notoriously inadequate in most European countries. In the case of Spain, the creation of the Airef represents an initial step in the right direction, which could inspire new initiatives. It is not just a question of guaranteeing an already existing administrative control of policies, but of functionally evaluating the implementation of programs according to the set of EU objectives.

Finally, a greater symmetry in the treatment of surplus and deficit countries would help address the current deflationary bias and pro-cyclical character of fiscal policies. Lacking a counter-cyclical European budget, the responsibility of supporting economic growth in a recession remains the responsibility of national governments, which, in practice, means that it lies with those countries that have a greater budgetary margin. A more symmetric adjustment would be consistent with debt criteria, insofar as surplus countries support investment and productive capital.

Creating a European fiscal stabilisation instrument

The creation of a counter-cyclical management instrument at the European level would solve many of the problems associated with the current system. Such an instrument would be able to directly confront asymmetric shocks, thus complementing national fiscal policies. To be efficient, such a tool would need to be quickly activated and also be provided with sufficient financial resources (Claeys et al., 2016). In the United States, the American Investment Act was enforced from the beginning of the crisis and played a decisive role in the recovery. Its available resources amounted to approximately 5% of GDP, and were allocated over a three-year period.

There are several options in this regard, but they all require a common fiscal capacity at the EU level, as well as the application of conditionalities to reduce moral hazard.

[8]

The first of such options consists of creating an investment fund similar to the American instrument. While there is a precedent (the Juncker Plan), this instrument is restricted to coordinating national investments, complemented by a modest European contribution through the European Investment Bank. Moreover, in principle, the Junker Plan’s resources are allocated proportionally to the economic weight of each country; the unemployment rate or business-cycle environment are therefore overlooked in favour of geographical allocation, which is consistent with a policy lacking supranational orientation.

A mechanism at the EU level would directly respond to the specific situation of each country. In order to be acceptable for all partners, its criteria should: i) explicitly acknowledge that the fund is not intended to aid a particular country, but rather any economy experiencing cyclical difficulties; ii) impose conditionalities (reforms improving market functioning, industrial policies aimed at enhancing the productive framework, etc.); and, iii) prevent countries from cutting their investment budgets (i.e., the replacement of national policies by a European instrument, which would be interpreted as a subsidy).

A second option would be the creation of a European fund to compliment national unemployment insurance systems. The initiative would automatically activate when the unemployment rate exceeds a given threshold, such as 3 percentage points above the average rate observed over a full business cycle. The main benefit of this method would be its prompt reaction to the business cycle, especially in comparison with the investment fund, which necessarily requires a relatively long gestation period to be operational.

A European unemployment fund contains elements that would limit opportunistic reactions by countries looking to cut social benefits in order to profit from EU aid (moral hazard). It should be noted that a rise in unemployment does not reflect well on national governments and cuts to social benefits would certainly hurt their image even more.

Another way of reducing moral hazard is to impose conditionalities. For instance, countries that access the fund should be required to introduce certain labour market reforms. Part of the aid could even be allocated to those programs which seem to be more efficient (i.e., strengthening of public employment services, the adoption of effective unemployed training methods, follow-up of unemployed placement policies results and of individual action plans).

The fund’s main drawback is the anticipated reluctance amongst those countries that have reached or are close to achieving full employment. The fund could therefore be designed to ensure that every country benefits from it at some point in time. The 3% threshold proposed here meets such criterium. In order to overcome this reluctance and appeal to their sense of European solidarity, the fund could reserve aid for young people. This could work in tandem with the Youth Guarantee Program, which already relies on European funding.

Lastly, some experts advocate for a fund without specific spending criteria, which could be used both to encourage investment, complement revenues, foster the creation of enterprises or limit bankruptcy rates. Since it would be adaptable to the priorities of each country, such a system would benefit from a high degree of flexibility. For instance, at the beginning of the 2000s, the Finnish economy was severely impacted by a recession in neighbouring Russia. However, the effects were concentrated in a single sector, which required a specific treatment, consisting of a combination of restructuring, training measures, and temporary subsidies to firms that had otherwise been profitable.

Ultimately, funding determines the degree of European responsiveness. Issuance of European debt securities is especially attractive due to both its flexibility and the excellent rating of EU institutions. This solution presents the additional benefit of not withdrawing resources from those countries which most need them.

Eurobonds, jointly guaranteed by European treasuries, would be used to finance the European macroeconomic management fund. Some countries are reluctant to support the introduction of eurobonds given the risks associated with a new source of debt. Moreover, they consider their current credit rating as evidence of their rigorous management of public finances. If eurobonds were issued, markets would reconsider their stance towards countries that balance their budgets without European aid. However, the battered finances of other countries would benefit from European support, especially in recessionary periods. A way of avoiding such risk is to insist that eurobonds issued during a recession must be repaid by beneficiary countries once economic conditions have improved.

If the European anti-crisis fund is a complementary unemployment insurance system, funding could come from countries’ social contributions. Since no eurobonds would need to be issued, the system wouldn’t negatively affect countries in good fiscal health. Moreover, each country would have to make an additional effort during expansion periods in order to earn the right to mobilize resources from the European system when they experience a sharp increase in unemployment.

Finally, the use of private financing is both possible and desirable if Europe introduces a European investment fund. In fact, private financing is a key feature of the Juncker Plan, and it could increase both the volume and share of national financing. Today, only a small proportion of resources come from the EU, and this amount can change depending on the situation of each country. Currently, there is a relative abundance of funds provided by the Juncker Plan in countries enjoying high growth, whereas there are scarce funds for those countries that most need them and present the most profitable investment opportunities. This situation could be avoided through the creation of the European investment fund.

To the extent that differences in national legislations may cause unfair competition, a certain degree of harmonization is required. This is particularly true for business taxation. Tax base differences, the treatment of royalties and the complex network of tax reductions lead to income transfers within business groups that eventually erode tax bases. This situation is detrimental to the public finances of all states, but especially to those that have established stricter criteria for equity between individuals and entities and have tenaciously fought tax evasion practices.

Moreover, EU policy could facilitate a real convergence of economies. Some analysts believe reform incentives or technical support from the Commission is best. However, it is a complex matter since it interferes with the priorities of each country. For instance, there is no single successful model of labour market reform. Recruiting and social protection can be initiated at the same time (Dutch model), or a government can prioritise flexibility (Anglo-Saxon model). The effects on income distribution are various, as are the consequences in terms of public expenditure. But empirical evidence shows that unemployment rates are similar in both systems. The task for Europe is to highlight tensions among different objectives and assess the impact on employment and convergence. That said, it does not seem reasonable to impose a single model on member states.

Finally, the reform of European fiscal policy, as presented here and in other analyses, opens up issues of democratic control. Various experts therefore propose the appointment of a European minister of finance, who would be accountable to the European Parliament. Furthermore, European competencies should be limited, especially regarding the management of the supranational fiscal mechanism and surveillance of national macroeconomic balances. Governance institutions of each country would still be responsible for the budget. In sum, the presence of a single currency entails a loss of national sovereignty in exchange for greater efficiency and solidarity. This is the critical dilemma which Europeans and their leaders will have to address.

Notes

An earlier version of this article was published by the same author in ICE (2018), under the title “Política fiscal europea: situación y perspectivas de reforma”. The author wishes to thank Patricia Sánchez Juanino and Romain Charalambos for their help with compiling the exhibits for this article.

See for instance the European Fiscal Board annual report (2017).

See IMF (2009), G20 London Declaration.

The specific value of the target is defined every three years (but always under the 1% limit), or even at more frequent intervals depending on the structural reforms adopted.

The EDP may also be activated when public debt exceeds 60% of GDP and in the absence of an adequate debt reduction plan.

For a recent analysis of interactions between fiscal policy and the financing of the economy by the ECB, see Jarociński, Marek and Maćkowiak, Bartosz (2017).

Such is the case of Spain (Torres and Fernández, 2018).

For a thorough discussion of all possible options as well as of the interaction with system incentives, see Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2018) and the review by Bini Smaghi (2018).

References

BEGG, I. (2018), “Reform of the EU fiscal framework,”

Funcas Europe (forthcoming).

BÉNASSY-QUÉRÉ, A.; BRUNNERMEIER, M.; ENDERLEIN, H.; FARHI, E.; FRATZSCHER, M.; FUEST, C.; GOURINCHAS, P.-O.; MARTIN, P.; PISANI-FERRY, J.; REY, H.; SCHNABEL, I.; VÉRON, N.; WEDER DI MAURO, B., and J. ZETTELMEYER (2018), “

Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform,”

CEPR Policy Insight, 91.

BERGER, H.; DELL’ARICCIA, G., and M. OBSTFELD (2018), Revisiting the Economic Case for Fiscal Union in the Euro Area, IMF Research Department.

BINI, L. (2018),

A stronger euro area through stronger institutions,

https://voxeu.org/article/stronger-euro-area-through-stronger-institutionsBOFINGER, P. (2018),

Euro area reform: No deal is better than a bad deal, VoxEU

BUTI, M.; GIUDICE, G., and J. LEANDRO (2018), “Deepening EMU requires a coherent and well-sequenced package,”

Voxeu,

https://voxeu.org/article/deepening-emu-requires-coherent-and-well-sequenced-packageCLAEYS, G.; DARVAS, Z. M., and A. LEANDRO (2016), A proposal to revive the European fiscal framework,

Bruegel Policy Contribution.

EUROPEAN FISCAL BOARD (2017), “Assessment of the prospective fiscal stance appropriate for the euro area,” June.

FATÁS, A., and L. H. SUMMERS (2017), The permanent effects of fiscal consolidations,

Journal of International Economics.

IMF (2009), G20 London Summit – Leaders’ Statement, 2 April 2009,

www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2009/pdf/g20_040209.pdfJAROCIŃSKI, M., and B. MAĆKOWIAK (2017), Monetary-fiscal interactions and the euro area’s vulnerability,

ECB Research Bulletin, 36,

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economicresearch/resbull/2017/html/ecb.rb170629.en.htmlTORRES, R. (2018), Política fiscal europea: situación y perspectivas,

Información Comercial Española, 903.

TORRES, R., and M. J. FERNÁNDEZ (2018), “The Spanish economy: Scenarios for 2018-2020”, Funcas,

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 7, No 2, March.

WIESER, T. (2018),

Fiscal rules and the role of the Commission, Bruegel.

Raymond Torres. Director for Macroeconomic and International Analysis, Funcas