The progress of Spanish banks’ solvency in a European context

In line with the general trend in Europe over recent months, Spanish banks have rapidly increased their solvency, bringing levels in line with the European average. While a challenging economic context will remain in place for the remainder of 2016, Spanish banks´ solvency does not appear to be a cause for concern.

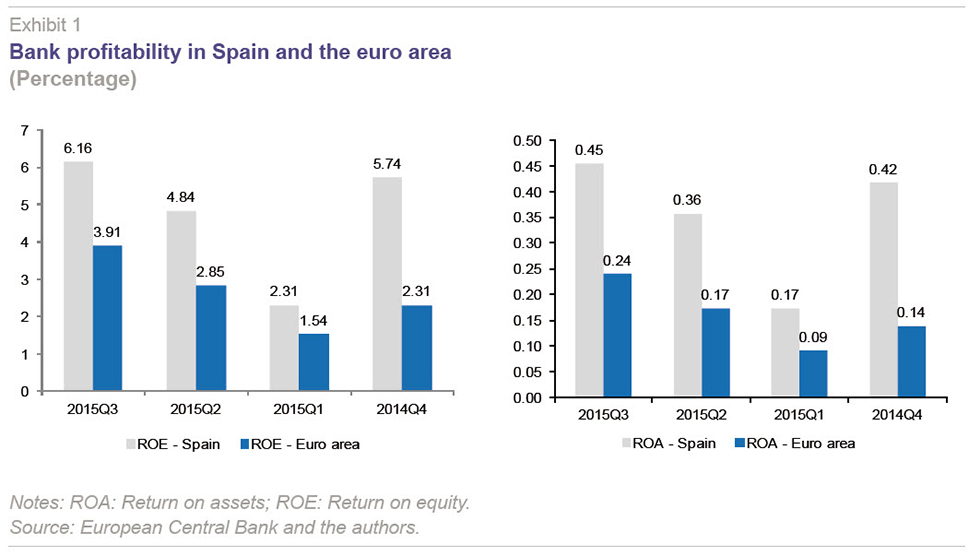

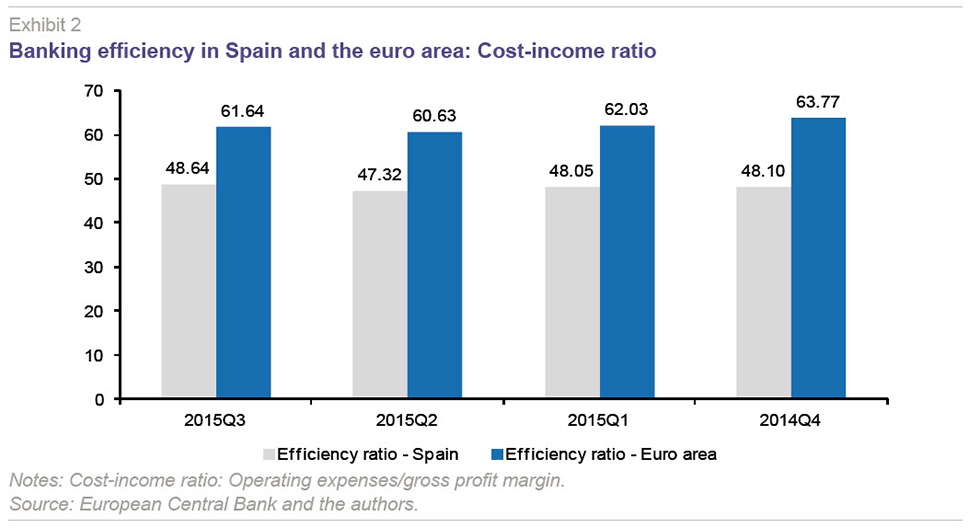

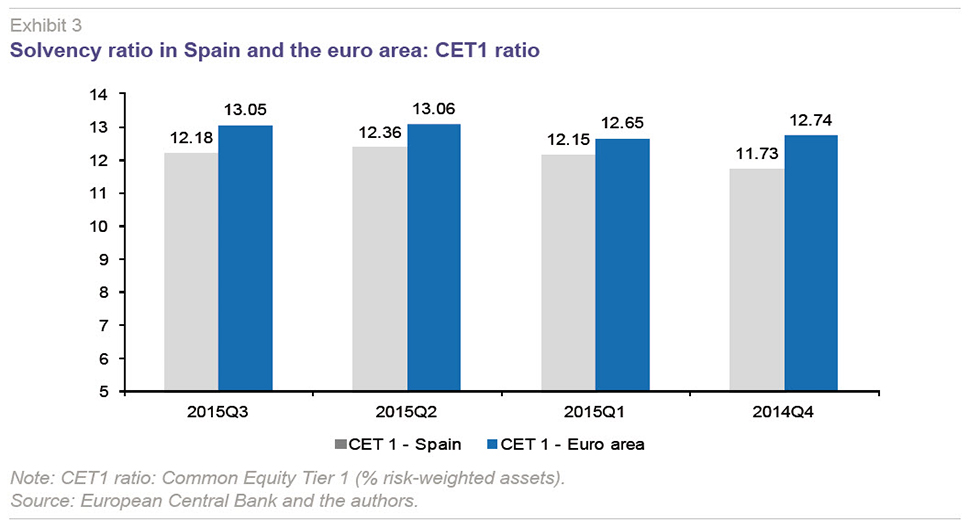

Abstract: Although capital increases are essential in the current context, their significance is difficult to interpret. As an example, several have taken place in Europe in recent months, giving rise to different readings. In Spain, there has been a relatively rapid increase in solvency, bringing capital levels up to the euro-area average. The Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio has risen to over 12%, close to the 13% euro area average. This has been boosted by two additional factors: a process of transparency, enabling balance sheet quality to be calibrated with relative certainty; and, a cost rationalisation effort that has made it possible for Spanish banks to hold on to their advantages in terms of higher profitability and efficiency than the euro-area average. Spanish banks´ return on equity (ROE) remains two percentage points above the euro-area average. The efficiency ratio (cost/income) in Spain is 48.64%, compared with a euro-area average of 61.64%. In any event, the consolidation of negative real interest rates, Brexit and the more pessimistic outlook for global growth since the start of the year continue to complicate the outlook for the banking sector in the second half of 2016. More specifically, Italian banks’ increasing default rate (now over 16%) is worrisome. The heterogeneous composition of risks and asset valuations across countries is also a concern, particularly, the German banking system’s high market risk weighting compared to its peers. In this context, it does not seem that Spanish banks’ solvency is a cause for concern, either in isolation or from a comparative standpoint with Europe as a whole.

Growing instability, blurred concerns

A number of European financial institutions have recently announced capital increases, including some based in Spain. However, these operations have been met by a degree of concern –perceptible in the media and, transitorily, in some share values– about the reasons underlying their seeking to strengthen their solvency. These reactions can be, in part, explained by the information asymmetries that have become particularly acute in such a turbulent market.

The European banking sector has been one of the hardest hit since the start of the year, and stock-market valuations are still quite low. However, the biggest problems since the start of the year have related to doubts over the valuations of certain assets in Germany and Italy. That banks increase their own funds, however, is logical at a time when both regulators and the market are demanding higher levels of solvency. Capital increases may also be driven by other strategic motivations, such as anticipating a provision or a change in asset valuation, raising capital for a takeover bid, or to protect against possible hostile takeovers.

Profitability remains the underlying challenge for the banking industry. However, it cannot be ignored that doubts as to the quality of certain investments and assets in a number of European countries´ banking sectors (particularly Germany and Italy) need to be dispelled more effectively than has been the case.

Moreover, the United Kingdom´s decision to leave the European Union will generate significant uncertainty and adds to the European banking sector’s concerns. The exposure to the UK of many banks based in other EU countries is significant, but the most important banks have detailed contingency plans in place.

However, in the weeks leading up to the referendum, the main concern was not so much the cross-holdings between British and European banks as Brexit’s possible effects on public debt holdings. Italy’s case is particularly delicate, as its banks have a bigger exposure to public debt and a rise in the risk premium could put Italian banks’ already damaged balance sheets in an even more delicate position. Banks in Italy, the euro area’s third largest economy, have around 360 billion euros in loans identified as problematic, and hold 419 billion euros of government debt on their balance sheets.

As we will discuss below, the banking industry in Europe faces a variety of risks, and at the same time, levels of transparency are uneven making it more difficult to identify these sources of uncertainty. On this point, we will show that the Spanish banking sector’s exposures are not only well provisioned, but that its balance sheets are probably the most transparent, precisely because they have been subjected to greater scrutiny.

Nevertheless, Spain’s financial institutions share concerns and strategies with their European peers. While the challenge of profitability is being met, the main short- and medium-term objective is to raise efficiency. A recent note from Fitch Ratings dated June 13th on the Spanish banking system illustrates the market view of these challenges. The agency praised the restructuring effort Spanish banks had made, not only retrospectively, but for the future adjustments announced. In line with its view on other European financial centres, Fitch states that, “We expect revenue generation to remain tough for Spanish banks during the second half of 2016 as persistently low interest rates continue to put pressure on margins and net new lending volumes are sluggish despite a strong recovery in economic growth. [...] Carry-trade opportunities, which supported margins at a few banks in previous years, are now scarcer [... which] will also contribute to the margin squeeze.” Fitch is confident, however, that progress reducing problem assets will ultimately have a positive impact on profitability.

The references to regulatory scrutiny point in the same direction. The latest Risk Dashboard report from the European Banking Authority in April 2016, using 2015 data from the banks under EBA supervision, reports that:

- EU banks’ capital ratios further increased.

- The quality of banks’ loan portfolios modestly improved, but remains a concern.

- Profitability remains low.

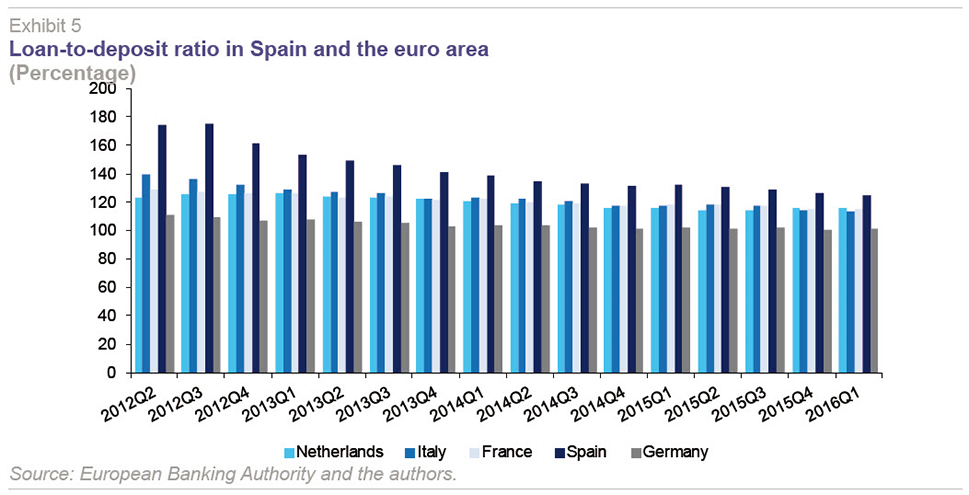

- The leverage ratio decreased but the loan-to-deposit ratio still averaged 120.9%.

A more recent short-term reference in the European Central Bank’s Financial Stability Review (May 2016) also said that turbulence in the first half of 2016 had affected banks’ stock-market valuations, although systemic risks remained under control. In line with the arguments outlined above, the ECB estimates that the outlook for improvements in profitability is limited given sluggish nominal growth and interest rates that are near zero or negative. The structural challenges identified by the ECB include the fact that “the large stock of legacy problem assets in some euro area countries continues to dampen banks’ profitability and weigh on their capacity to extend new loans.” The ECB similarly said that “structural challenges to bank profitability could also arise from overcapacity.”

Relating to this reasoning about transparency problems in certain European banking sectors, the ECB remarks that “a complete assessment of financial stability risks remains hampered by a dearth of harmonised reporting.” It therefore calls for higher quality macroprudential supervision over the coming months.

Meanwhile, the ECB remains the cornerstone of market liquidity. The latests data from the Bank of Spain on Eurosystem financing, published on June 14th, indicate that European banks obtained 311,043 million euros through the ECB’s asset purchase programmes between January and May 2016. Over this same period, Spanish banks obtained 42,259 million euros from the programme.

Nevertheless, banks remain affected by volatility and events, such as Brexit, could make it necessary to step up expansionary monetary measures.

The search for returns: Efficiency as the bridge

The challenge of restoring banks to profitability is half way through a period of transformation and assuming a new business reality. Pre-crisis profits per share (or per asset) were perhaps too high to be sustainable over the long term. However, markets and shareholders are demanding higher returns than at present, and this is difficult to achieve in a scenario of negative real interest rates. Exceptionally, from the historical point of view, liquidity is abundant, but the margins that can be obtained from it are slender.

The challenge of bank profitability is both global and European, and in no way specific to Spanish banks. Indeed, Spanish banks are sustaining higher levels of returns on equity (ROE) and on assets (ROA) than their counterparts elsewhere in the euro area. The left pane of Exhibit 1 shows how Spanish institutions’ ROE has been around two percentage points higher than the euro-area average and that in the third quarter of 2015 (the most recent data available) it stood at 6.16% compared to 3.91%. Spanish banks’ ROA was twice European levels, and at the end of the period considered, stood at 0.45% compared to 0.24%.

While the income route is constrained by market conditions, and the business models need to be transformed, European banks are at an impasse. They therefore need to advance their restructuring in order to correct their excess capacity. As reported in previous editions of

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook (SEFO), relative to other countries, Spain has made strong progress towards simplifying structures. It should thus come as no surprise that the Spanish banking sector remains among the most efficient. As Exhibit 2 shows, the efficiency ratio in Spain is 48.64%, compared with a euro-area average of 61.64%. This means that Spanish banks need to consume significantly less gross margin to cover their operating expenses.

Solvency: More than just capital ratios

The data given in the previous section suggest that the Spanish banking industry has profitability and efficiency advantages relative to the European average. But what has happened to solvency levels? Do the capital increases underway give grounds for concern? To answer these questions, the first step is to determine the starting point. Spain’s financial institutions had to make substantial write-downs during the crisis.

The Spanish banking industry underwent a process of enhanced transparency regarding the quality of its assets that was almost unparalleled in Europe.

A third significant point is that the solvency ratios are a benchmark constructed based on assumptions of uniform quality of the valuation of asset quality, which as noted above, is questionable in some countries. It is not a question of whether this quality is higher or lower, but that it is adequately valued and provisioned.

Exhibit 3 suggests that, after the intensive write-downs and recapitalisation of recent years, Spanish banks are now at levels of solvency –measured using the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio now used– close to euro-area averages, and in some cases, significantly above minimum regulatory requirements. Using uniform ECB data, the most recent data available shows a CET1 ratio of 12.18% compared to the euro-area average of 13.05%.

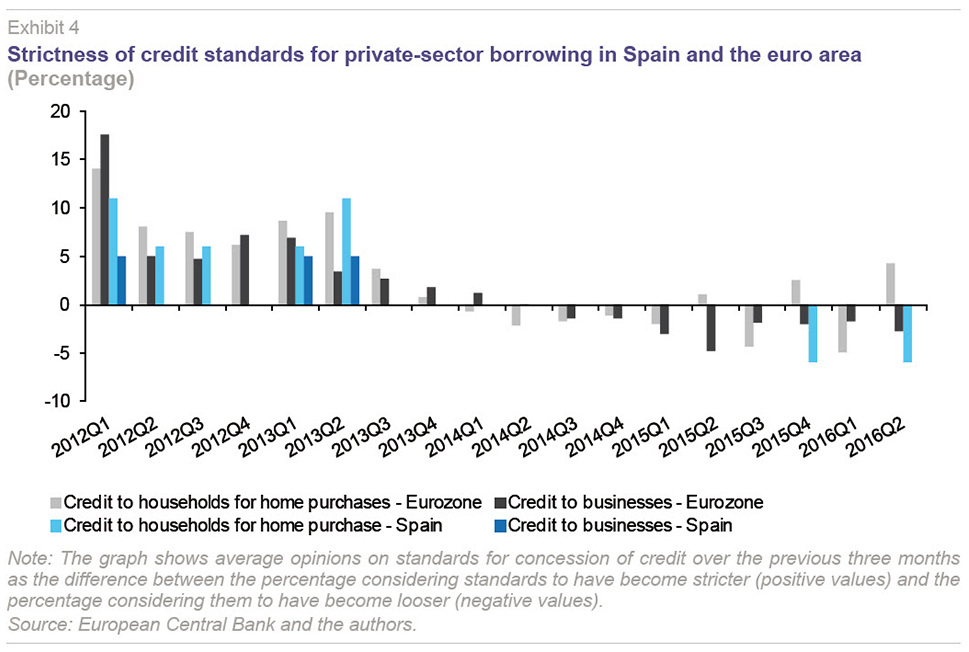

Nor does the risk exposure seem to have changed significantly over recent months. The results of the ECB’s latest bank lending surveys suggest that in 2014, 2015 and the first half of 2016, there has been a progressive, but relatively prudent relaxation of credit standards after years of sovereign risk tensions. Exhibit 4 shows the degree of strictness/laxity of credit standards as the difference between the percentage of positive valuations (hardening) and negative valuations (relaxation), confirming a progressive but moderate trend towards more relaxed credit standards in order to encourage borrowing.

Another measure used to calibrate the risk exposure is the loan-to-deposit ratio. Spain started out with this indicator at a high level before the crisis, suggesting lending was high relative to savings attracted as deposits. As Exhibit 5 shows, Spain is progressively converging towards other European countries’ averages of around 120%.

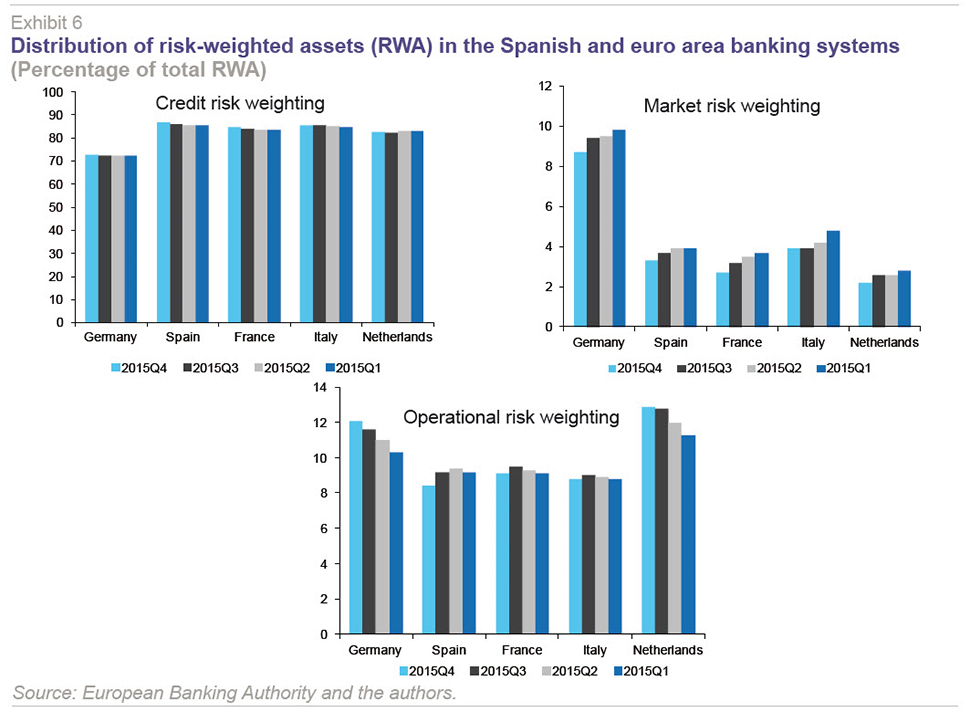

Part of the heterogeneity in the valuation of asset quality derives from the composition of risk- weighted assets (RWA), which are the denominator for the capital ratios. Apart from the uneven way in which RWAs are treated in different euro area jurisdictions –a matter of debate that requires detailed analysis– there are highly illustrative differences in the composition of RWA itself, as Exhibit 6 shows. As might be expected, the risk associated with the credit portfolio accounts for the bulk of RWAs. However, this risk is around 80-90% in most countries considered, with the exception of Germany, where it is around 70%. In this regard, in the German banking sector, market risk accounts for a bigger share of RWAs (9-10%), and this is an exposure whose valuation is more complex, about which the information is less transparent, and to which significantly less attention has been paid. Operational risk –including legal risk and risks arising out of procedures that may result in differences between current and potential asset valuations– also has a considerable weight in Germany and the Netherlands (12-13%) in relation to the other sectors considered (all of them around 8-10%).

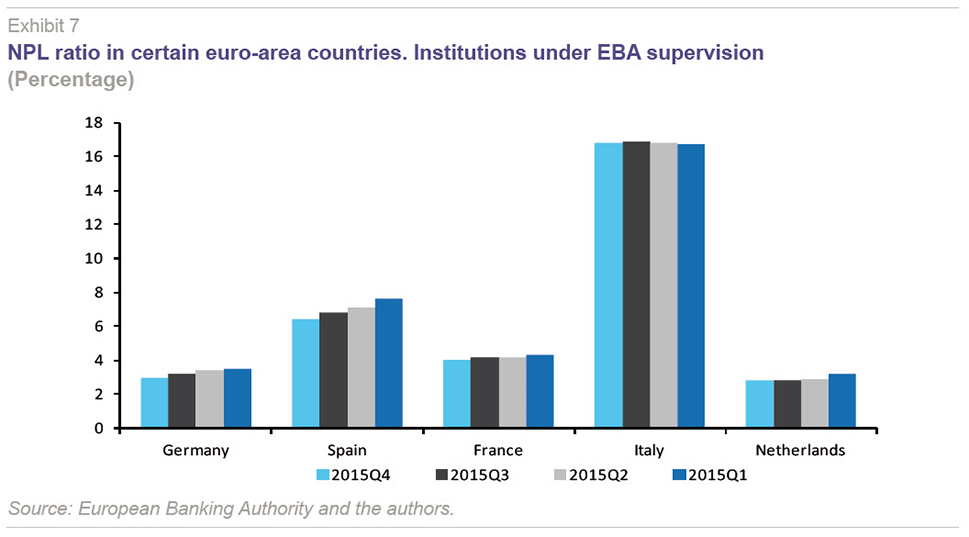

Nor does Spain seem to be a concern as regards non-performing loans. Exhibit 7 shows data for institutions under EBA supervision. The default rate in Spain is dropping rapidly. The concern, however, centres on Italy, where the ratio is over 16% and rising. As was suggested in previous issues of SEFO, the initiatives taken to manage this deterioration in the balance sheet – such as the asset management company Atlante – do not inspire confidence that they will be successful.

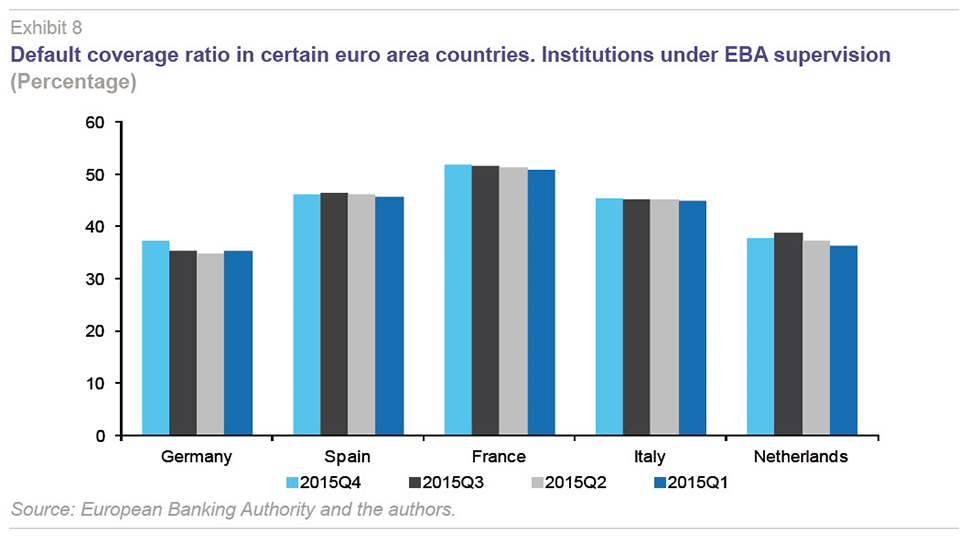

Spanish banks are also in a strong position in terms of allowances and provisions for default. The EBA’s data show that at the end of 2015, the coverage ratio was over 45% in Spain, while in countries, such as Germany and the Netherlands it was below 40%.

Concluding remarks

The data analysed in this article confirm that the Spanish banking sector has improved its levels of solvency and is close to eurozone averages. The process of recapitalisation in both Spain and other countries may be a response to various strategic imperatives, although in most cases it aims to meet regulatory pressure to increase own funds.

Moreover, based on the data analysed, three further points may be mentioned concerning the solvency of the Spanish banking sector from the European perspective:

- Profitability in Spain remains above the eurozone average. The search for efficiency gains –among other factors, through restructuring– has allowed Spanish banks to remain among those with the lowest cost-to-income ratios in the euro area.

- The composition of risk-weighted assets (RWA) is very uneven across Europe. The proportion of these assets corresponding to market or operational risk in countries, such as Germany or the Netherlands, is striking.

- The quality of assets is as important as their correct valuation. The enhanced transparency to which Spanish banks have been subject has represented an advantage in this respect. Examining the evolution of indicators, such as non-performing loans and default provisions, seems to be assuaging concerns in some countries, such as Spain, while shifting the focus towards others, such as Italy.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas