The performance and role of Spain’s social economy throughout the crisis

Spain was one of the countries most affected by the recent crisis since 2008. The resilience of Spain´s social economy, which currently accounts for 10% of the country´s GDP, has played a noteworthy role in mitigating some of the negative impacts of the crisis on society.

Abstract: The social economy comprises a series of organisations combining economic efficiency and social utility, resting on shared values and principles. It is significant both economically and in terms of the number of people involved, and it is growing continuously in Europe. However, in most countries, it has a low institutional profile, particularly at times of economic growth and dynamism. Drawing on official statistics on the social economy in Spain, this article analyses the performance of the sector’s main entities during the latest crisis. The aim is to assess how they have withstood the recession, and, in particular, determine whether this context has allowed them to utilise their specific capacities and characteristics. We find that the sector has not escaped from the recession, although some types of entities have been harder hit than others. Overall, the social economy has withstood the downturn better than the wider economy and has managed to significantly mitigate the effects of the crisis on society, highlighting its countercyclical nature.

Since the 1970s, there has been growing interest worldwide in the so-called “third sector,” which comprises organisations that are neither public nor private for-profit enterprises. These are private entities whose purpose is to provide services to their members or to the community rather than profit for their owners. Whereas in the English-speaking world, the third sector, or non-profit sector, is based on a strict non-profit criterion, and therefore only includes non-market organisations, such as associations and foundations, in continental Europe, the third sector is synonymous with the social economy, and so also includes market organisations operating through business initiatives, such as cooperatives and mutual societies. Another characteristic feature of the social economy is the centrality of the principle of democratic governance (“one person, one vote”) among its entities.

Despite the difficulty of defining and treating the social economy as a unified sector, and given its lack of institutional recognition throughout Europe, there is agreement over its relevant economic and social contribution. According to the main estimates (Chaves and Monzón, 2012; European Commission, 2011), at the start of the economic crisis (2009-2010), the social economy represented 10% of all firms in the European Union and 6.5% of total paid employment. Between 2003 and 2010, paid work in the sector grew by 26.8% EU-wide. Spain stands out in the EU for the size of its social economy. Supported by the Constitution (Art. 129.2), the sector –comprised, in particular, by cooperatives and other similar structures, such as labour companies (“sociedades laborales”) –accounted for over 10% of Spanish GDP and 6.7% of total employment at the start of the crisis in 2008 (Chaves and Monzón 2012; Chaves, Monzón and Zaragoza, 2013). Moreover, in 2011, Spain also became the first European country with a specific law regulating the social economy (Law 5/2011, March 29th, 2011). This recognises for the first time the set of structures making up the social economy, assigning them common principles and a role as social partners vis-à-vis the public authorities. The law also contains ambitious targets and measures to enact public policies to support the sector.

Although the dynamic is favourable and the outlook positive, the situation is nevertheless fragile. Against this backdrop, this article sets out to assess how these social economy entities have weathered the crisis. The evidence suggests that although the sector has not avoided the effects of the economic recession: i) it has been more resilient than the rest of the economy; and, ii) has acted as a shock-absorber against the impact of the crisis.

The negative impact of the crisis on the social economy

Like the rest of the economy, Spain’s social economy was affected by the deterioration of the economic situation that became apparent in 2008. The crisis affected the sector in different ways and with differing intensities depending on the type of structures involved.

The impact on market-dependent entities (market sub-sector)

Cooperatives and labour companies, in which the company’s share capital is mainly owned by workers and no member can hold more than a third, have been hard hit by the economic crisis. The main impact has been a weakening of their order books, threatening jobs and income, and even their ultimate survival.

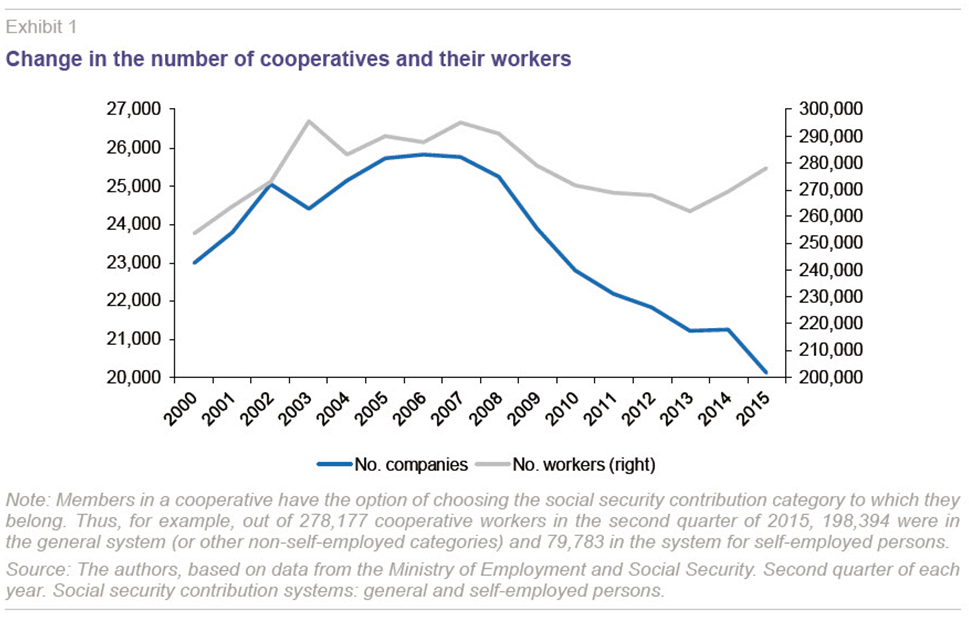

Between 2007 and 2015, the number of cooperatives in Spain fell by 22% and employment in cooperatives contracted by 5.8% (11.3% to 2013, before the start of the economic recovery, as shown in Exhibit 1).

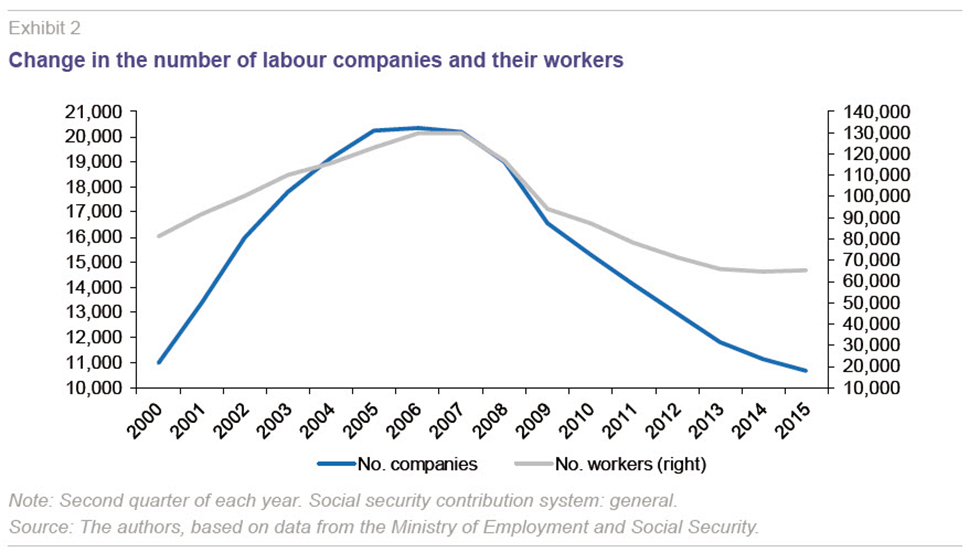

In 2007, 30% of jobs in labour companies were in construction, a sector that was devastated by the crisis in Spain, making them the hardest hit. The number of labour companies and jobs in these companies have fallen by 50% since the start of the crisis (Exhibit 2). There were only 10,675 entities in the second half of 2015 (89% limited liability, 11% joint-stock) employing 65,518 people.

The impact on entities dependent on public funding (non-market sub-sector)

Social economy entities that depend essentially on public funding, particularly associations and foundations, have not been left unscathed by the crisis. Indeed, they have been particularly affected by cuts in public spending. A general drop has been observed in income from public sources for the social action third sector in Spain, particularly as of 2011. Although public funding continues to provide the bulk of their income (55.3%, far exceeding the 25.3% of own funding and the 19.4% of private funding) there was a drop of 23.6% in public funding for the social action third sector between 2010 and 2013 (Plataforma de ONG de Acción Social, 2015). Associations and foundations have been unable to avoid some of the disastrous consequences of the dual challenge of declining external funding and increasing social demand, including: financial difficulties, deterioration of organisations and their capacity for action, staff cuts, and closures.

Special employment centres (

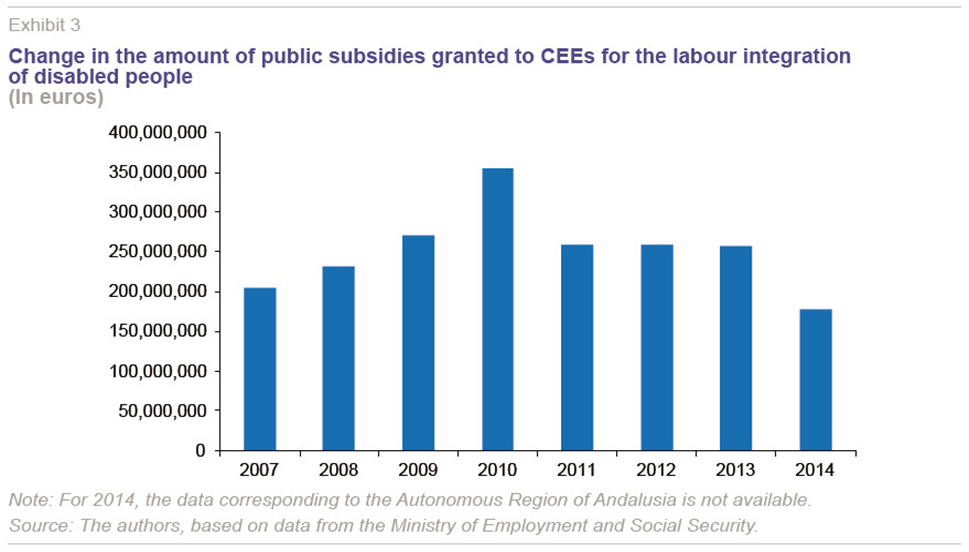

Centros Especiales de Empleo, CEEs in their Spanish initials) have also suffered from a reduction in state aid and other cutbacks. Up until 2010, public subsidies for these centres, which aim to support the labour integration of disabled people, grew continuously (Exhibit 3). In 2011, there was a sharp drop (-27% from the previous year), and again in 2014 (-31% compared to the previous year).

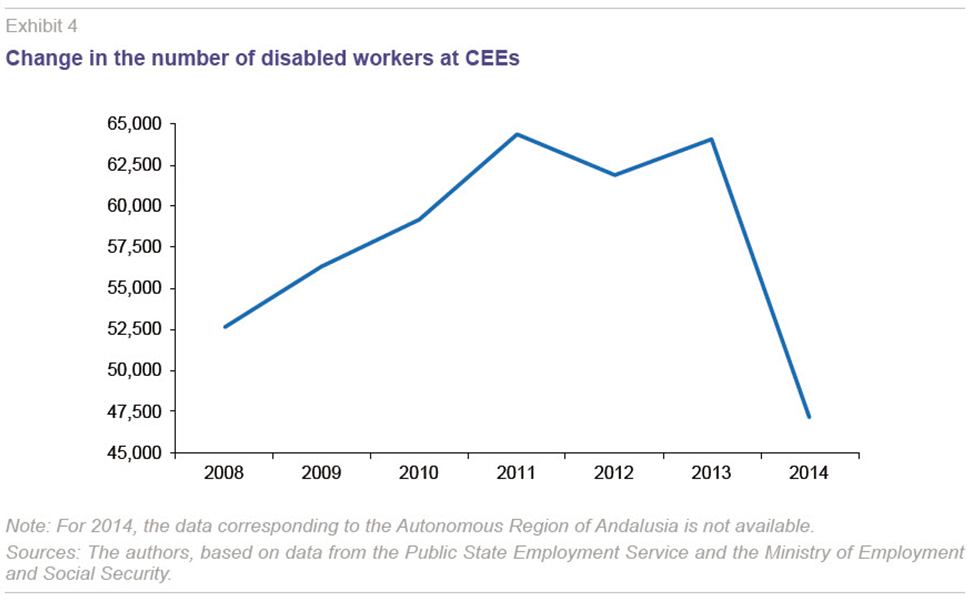

As well as the centres’ reduction in activity due to the crisis, the decrease in public subsidies led to a stabilisation of their workforce in 2011 and a dramatic fall in 2014, as Exhibit 4 shows (dropping from around 64,000 disabled workers in 2011 and 2013 to 47,131 workers in 2014).

As a comparison of Exhibits 3 and 4 shows, changes in subsidies are reflected directly in employment.

The sector’s resilience and its role as a shock-absorber throughout the crisis

Despite the aforementioned unfavourable factors, overall, the social economy has been more resilient than the economy as a whole, and has made it possible to limit the effects of the crisis significantly in several ways, such as: company survival, job creation, social and labour integration, combating exclusions, and social welfare.

Company survival

An analysis of overall survival of companies created in Spain just before (2007) or during the recession (2009) suggests that social economy enterprises have withstood the crisis better than other businesses. According to harmonised business demographics data from the National Statistics Institute (INE), of the companies created in 2007 (356,358 in total), just 54.4% remained in business three years later (2010). The corresponding figure was 62% among cooperatives. As regards the companies created in 2009 (a total of 267,546), while approximately half (53.8%) remained after three years (2012), 56.9% of cooperatives and 62% of labour companies (limited and joint-stock) had survived. Labour joint-stock companies created in 2009 were more resilient throughout the crisis than the other companies created that year.

Job creation

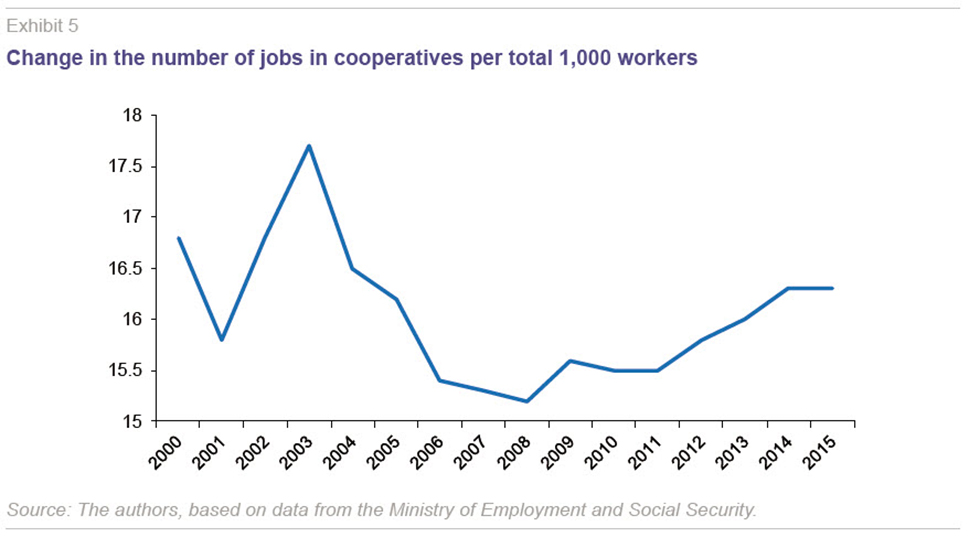

Cooperatives are also seen to have created more stable jobs than the rest of the economy. As Exhibit 5 shows, in 2007 there were 15.3 jobs in cooperatives for every 1000 workers in Spain. The equivalent figure in 2015 was 16.3, representing an increase in employment in cooperatives of 6% in proportion to the total number of people in work in the period 2007-2015. This increase is doubled when comparing the number of jobs in cooperatives with total employment in the Spanish private sector.

[1]

Led by worker cooperatives (cooperativas de trabajo asociado), whose aim is to provide their members with work (“worker members”), we can even see a significant increase in employment in cooperatives in absolute terms between 2007 and 2015 in key sectors such as education (19%) and health-care and social services (28%) – the sectors that saw most public-sector job losses in the crisis. This atypical trend during the recession, alongside their relative slowness to create jobs during periods of economic expansion (notice the drop in the curve in Exhibit 5 between 2003 and 2007 while Spain’s annual economic growth was over 3%) reveals cooperative employment’s countercyclical behaviour, a feature that has been noted in previous studies (Grávalos and Pomares, 2001; Díaz and Marcuello, 2010).

Social and labour integration

As well as reducing the amount of public money spent on social protection by turning potential recipients of social services into workers, taxpayers and consumers, special employment centres and reintegration enterprises (

empresas de inserción) have been an effective mechanism for integrating people who would otherwise face major obstacles in the labour market and in society and so helping reduce their risk of facing poverty and social exclusion. This is particularly the case for disabled people.

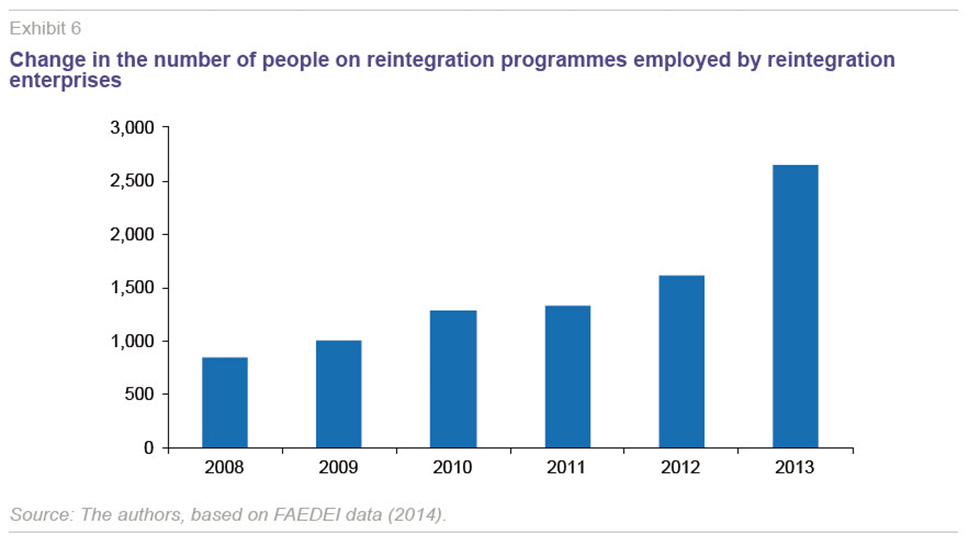

[2] The number of people working in reintegration enterprises (including recipients of a guaranteed minimum income, the long-term unemployed, people with drug dependency, etc.) has risen constantly over the last few years, according to data from the Federación de Asociaciones Empresariales de Empresas de Inserción (FAEDEI, 2014), based on a large sample of companies (Exhibit 6). In 2013, at least 905 people working in a company of this type (35% of reintegration workers) had previously been receiving a guaranteed minimum income.

Combating exclusion

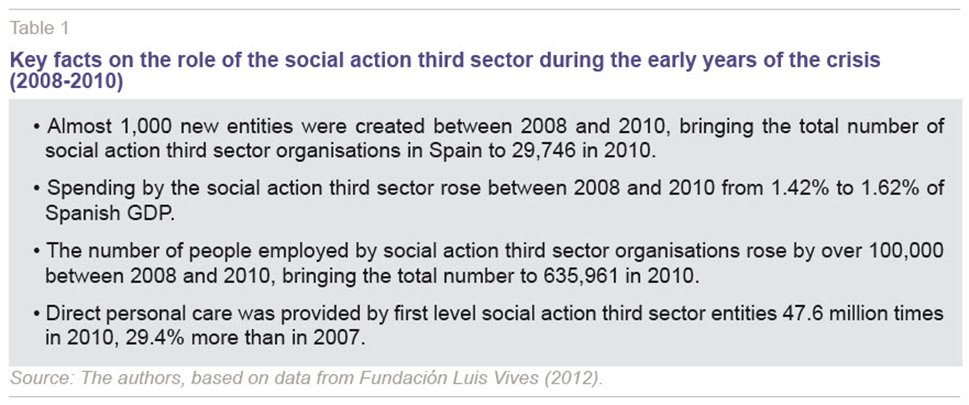

In light of the considerable numbers of people requesting help of various kinds and the re-emergence of basic social needs, associations and foundations have adapted to the new environment by stepping up their activities and giving priority to the role of social protection. The social action third sector can be seen to have undergone a tangible shift towards providing welfare during the crisis, concentrating almost exclusively on addressing urgent needs and providing basic services (and not, for example, demanding rights, social advocacy or raising awareness). The upward trend in some of the figures for these organisations’ expenditure at the start of the crisis (2008-2010), and the number of entities created, employees hired, or welfare services directly provided by them, confirms this increase in welfare activity (Table 1).

Social welfare

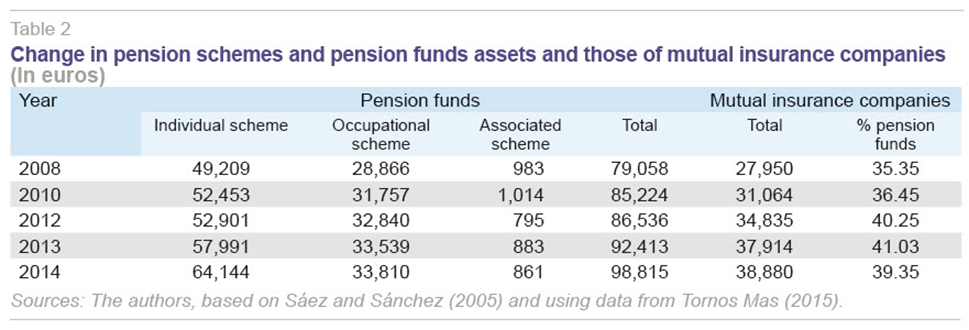

Finally, analysis of how some of the aggregate figures on mutual insurance societies have changed during the crisis highlights the sector’s good standing (Confederación Española de Mutualidades, 2008-2014): premium income,

i.e. from sales of insurance, has risen by 27.6% since 2008, from 2,360 to 3,260 million euros at the end of 2014. Aggregate assets (equity) came to 38,880 million euros at the end of 2014, a figure 28.6% higher than at the start of the crisis. On this latter point, mutual insurance companies have also seen strong growth in their assets in relation to pension funds, which constitute the most widely used instrument in the complementary welfare market in Spain (Table 2). Mutual insurance companies’ assets were equivalent to almost 40% of that of pension schemes and pension funds in 2014.

Concluding remarks

Like the Spanish economy as a whole, the social economy has been hit hard by the crisis. Nevertheless, the sector has proven to be particularly dynamic during the past few years, thus confirming its counter-cyclical nature. This trend has manifested itself in the recent performance of employment in cooperatives. More than just a shock-absorber for the impacts of the crisis, its structures, in conjunction with its combined economic and social utility, have performed a far from insignificant role in the country’s economic recovery.

As well as its considerable capacity to provide welfare to the most vulnerable in society – whose number has grown significantly in the past few years – and foster their integration, and to develop external solidarity such as voluntary work

[3] and networking – inter-cooperation – between social economy entities, these organisations have been supported in particular by the specifics of their legal basis to navigate and withstand the crisis. In particular, they have been able to draw upon their principles of operation, management and governance – such as the limited distribution of their surpluses, the double quality rule

[4] and their participatory governance – to establish long-term strategies and strengthen themselves against cyclical fluctuations.

The crisis has therefore acted as a mechanism revealing the specific capacities of social economy entities to act in response to today’s structural and cyclical changes. This new visibility for a sector which is often hidden in the background has stimulated the interest of the public and politicians in the social economy’s structures and practices. This has been complimented by an increase in number of Spanish citizens appreciating these entities, not just as a palliative of the crisis or transition between cycles, but as an alternative economic model, with its own goals, specific features, and role in socio-economic relationships structuring society.

Notes

According to INE data on private employment, the number of jobs in cooperatives rose by 11% in proportion to the total number of people working in the private sector over this same period, rising from 16.7 jobs in cooperatives for each 1000 private sector jobs in 2007 to 18.7 in 2015.

According to data from the Atlas Laboral de las Personas con Discapacidad 2016 (Grupo SIFU and the University of Seville), the unemployment rate among disabled persons rose from 16% to 35% between 2008 and 2013. It grew more than the rate among persons without a disability (11.3% in 2008 and 26% in 2013), which represents a widening of the gap between the two groups from 5 to 9 points. The study also revealed that a third of the population with a disability is living in poverty and social exclusion, and that of the total number of disabled persons in work, 12.6% are at risk of poverty.

It is estimated that almost 1.3 million people were working as volunteers in the social action third sector in 2013 in Spain, an increase of 31% on 2008. Volunteers take part and involve themselves actively in the sector’s operations: in 2013 they were involved in intervention or direct welfare provision to beneficiaries in over 80% of entities (Plataforma de ONG de Acción Social, 2015).

The double quality rule (double qualité in French) refers to the fact that users or beneficiaries of the activity are also members of the structure which creates it.

References

CHAVES, R., and J. L. MONZÓN (2012),

L’économie sociale dans l’Union Européenne, Rapport d’information élaboré pour le Comité économique et social européen par le Centre international de recherches et d’information sur l’économie publique, sociale et coopérative (CIRIEC), Brussels.

CHAVES, R.; MONZÓN, J. L., and G. ZARAGOZA (2013), “La economía social: concepto, macromagnitudes y yacimiento de empleo para el Trabajo Social,”

Cuadernos de trabajo social, Vol. 26-1: 19-29.

CONFEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE MUTUALIDADES – CNEPS (2008-2014),

http://www.cneps.es/DÍAZ FONCEA, M., and C. MARCUELLO (2010), “Impacto económico de las cooperativas. La generación de empleo en las sociedades cooperativas y su relación con el PIB”, CIRIEC-España,

Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, no. 67: 23-44.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2011), “Social Business Initiative. Creating a favourable climate for social enterprises, key stakeholders in the social economy and innovation,” communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM (2011) 682 final.

FEDERACIÓN DE ASOCIACIONES EMPRESARIALES DE EMPRESAS DE INSERCIÓN – FAEDEI (2014),

Memoria Social 2013, Madrid.

FUNDACIÓN LUIS VIVES (2012),

Anuario del Tercer Sector de Acción Social en España, Madrid.

GRÁVALOS, M. A., and I. POMARES HERNÁNDEZ (2001), “Cooperativas, desempleo y efecto refugio,” REVESCO,

Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, no. 74: 69-84.

PLATAFORMA DE ONG DE ACCIÓN SOCIAL (2015),

El Tercer Sector de Acción Social en 2015: Impacto de la crisis.

SÁEZ FERNÁNDEZ, F. J., and M. T. SÁNCHEZ MARTÍNEZ (2005),

Las Mutualidades de Previsión Social y los Sistemas de Protección Complementarios, Universidad de Granada, Fundación Once, Documento de Trabajo, no. 3.

TORNOS, E. (2015),

Balance social y económico de las Mutualidades. Propuestas ante los cambios normativos, Confederación Española de Mutualidades.

Pierre Perard. Funcas