The Spanish property sector: Recovery or stabilisation?

The Spanish property sector is undergoing a much-needed correction, albeit stabilising rather than significantly recovering. Nevertheless, the construction sector is expected to contribute positively to Spanish GDP and employment over the coming years.

Abstract: The Spanish property market is undergoing a notable correction. However, a closer look at the sector´s recent performance reveals it is more of a stabilisation than significant recovery. Housing price data suggest that prices rose slightly in early 2015, but the strength of the upturn is questionable, and various sources suggest prices fell back down again in July and August. Similarly, although the number of mortgages rose, the amount of new credit being extended for home purchases is substantially lower than in the years before the crisis. Moreover, there are a number of reasons why transactions are not directly comparable with those taking place in the years of the housing bubble, such as the fact that only around a third of recorded housing sales are being financed with mortgages. While price, transaction and financing indicators remain below pre-crisis levels, the construction sector will likely continue to increase its contribution to GDP and employment in Spain over the years ahead.

Consensus on moderate improvement

The role played by the property sector and its financing in Spain´s recent crisis is already well documented. Its scale and social implications have resulted in a certain stigmatisation of everything related to the construction industry. Moreover, calls for greater diversification of Spain’s production model, which had already been widespread before the crisis given the large share of services and property-related activities in GDP, have once again resurfaced.

Diversifying production is both necessary and healthy for the sustainability of growth, but it can only be achieved by pressing ahead with structural reforms. Moreover, diversification does not imply that construction will not have a more significant role to play in the wider economy, or at least a bigger role than in recent years, merely that it will not be anywhere near the contribution made during the property boom.

Several indicators in recent months have hinted at a correction in the property sector, which has accounted for a substantial share of job creation. There is also considerable media coverage of increased bank competition in the area of mortgage lending. This information has sometimes led to claims that the sector is in the midst of recovery, and has renewed concerns over reliance on some of the same practices that led to the creation of the property bubble in the past. However, as this article shows, it is difficult to substantiate the existence of these risks at present. Indeed, it is difficult even to talk of a recovery in the property sector, because the data suggest that, at most, we are witnessing a stabilisation. Furthermore, none of the data supporting an improvement in the indicators relating to housing, construction or its financing are comparable to those seen in the run up to the crisis.

Evidence of stabilisation has been highlighted in some of the recent reports by official international and national organisations. For instance, in its report on Spain, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) report n.15/232 (2015) Article IV consultation–Staff report; and statement by the Executive Director for Spain said that “There are also signs that the real estate sector might have begun to turn the corner. After a long period of decline, housing prices started to increase moderately in the second half of 2014–albeit unevenly across regions–and investment and employment in construction have started to recover.”

Also, on the financial front, the IMF suggests that the recent upturn in lending flows bears no relation to pre-crisis practices, stating that “new credit is being extended, especially to non-financial corporations outside real estate and construction with healthy financial positions. New household credit is also growing. The improved credit outlook is mostly demand driven.”

Additionally, the Bank of Spain, in its July/August Economic Bulletin, shares the view that there has been something of a recovery in the sector, but manages expectations by pointing out that “the most recent data from up-to-date indicators of construction activity suggest the sector’s dynamism has been maintained. However, it could be undergoing a slight deceleration. In the case of labour market indicators, year-on-year growth of social security affiliations in the sector moderated to 5.3% in June while among the data on intermediate consumption, the progress of apparent consumption of cement slowed to 8.2% in terms of the seasonally adjusted series. Nevertheless, the faster pace of new building permits in April, for both residential and non-residential construction, confirms the ongoing trend towards a recovery in construction activity.” It therefore suggests that the picture has improved, but only moderately and unevenly.

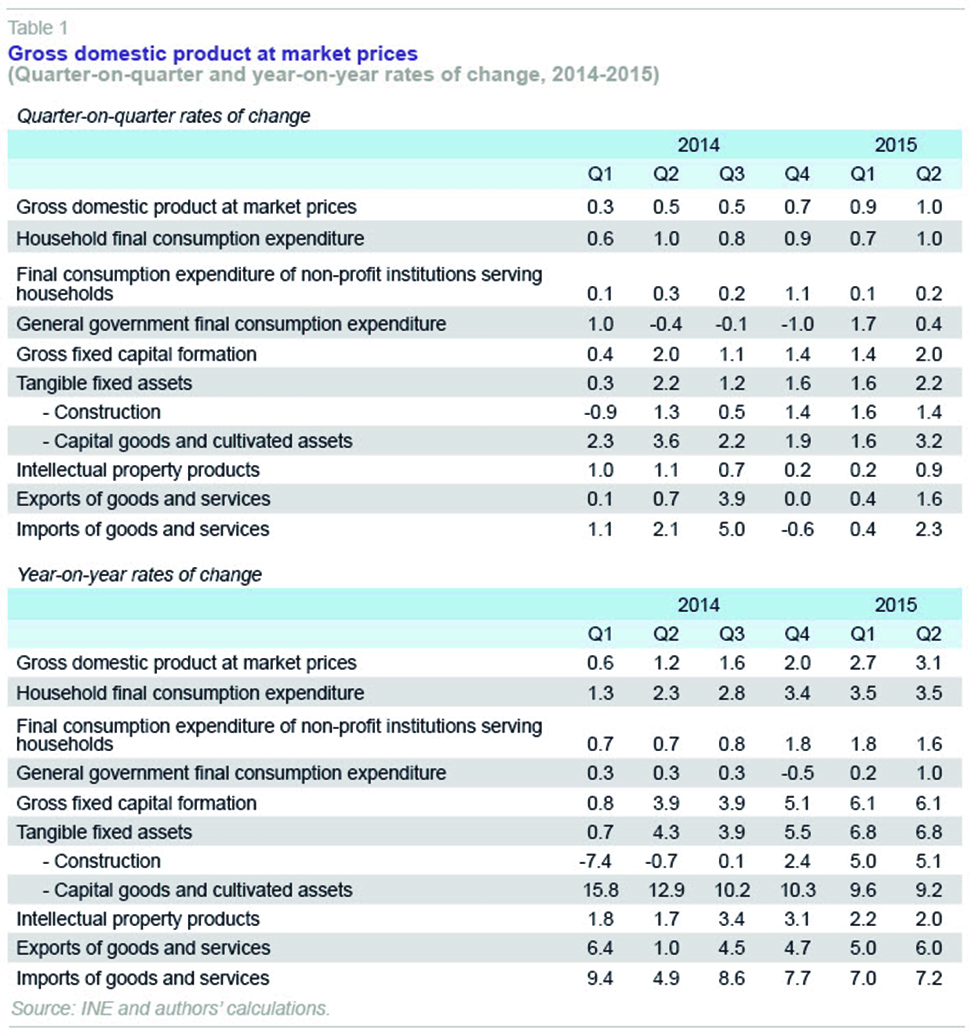

The second quarter national accounts data, provided by the National statistics institute (INE) at the end of August (Table 1), suggest quarter-on-quarter growth in construction activities of 1.6% in the first quarter of 2015 and 1.4% in the second quarter, contrasting with -0.9% and 1.3% in the same quarters of 2014. In year-on-year terms, investment in construction assets went from 5% to 5.1% between the first and second quarter of 2015, well above the changes in GDP analysed for these two periods, which were 2.7% and 3.1%, respectively. The INE considers “the performance of both housing investment and other construction investment” to have made a contribution.

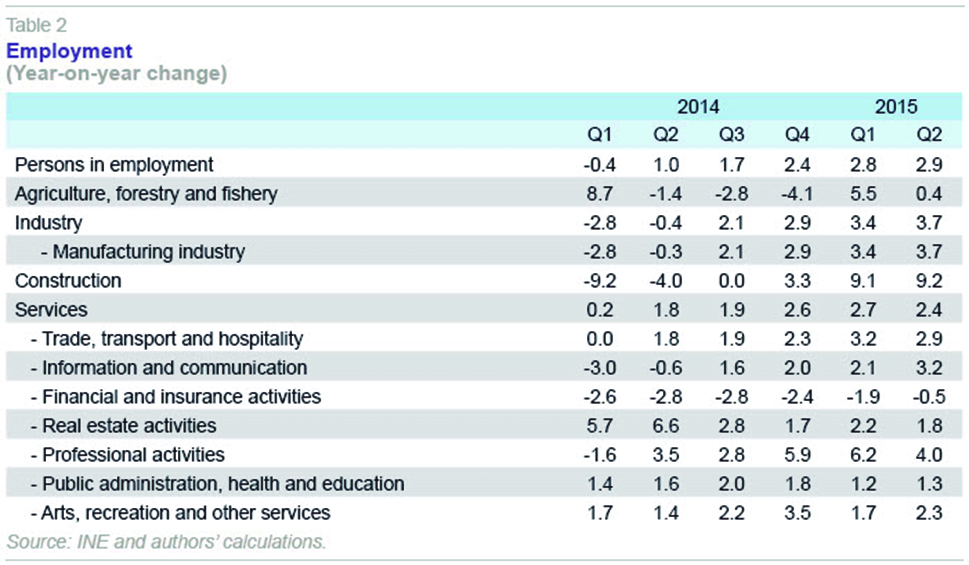

Employment has performed favourably over the last few quarters. The Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the second quarter of 2015 showed a quarter-on-quarter increase in employment of 0.7% according to the seasonally adjusted series (0.6% in the first quarter). According to the LFS, with a year-on-year rate of 3%, employment creation was particularly strong in construction (11.6%), which has risen by 16% from the minimum reached in early 2014.

On the aggregate level, national accounts data offer a similar estimate to the annual change in employment in the second quarter of 2015, situating it at 9.2% (9.1% in the first quarter as shown in Table 2). However, this increase is relative to a very low starting point for employment in the sector. Just one year earlier, the annual change was a drop of 9.2% in the first quarter and 4% in the second.

Housing prices: Erratic and uneven progress

Housing prices are typically viewed as good indicators of the progress of the real estate sector. Statistics vary and in Spain they all have limitations either because they only cover a specific portion of transactions or because they are based on land register or valuation data. Whatever the case, there are three main groups of price statistics. The main indicators based on valuations include the “official” prices from the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, and private valuations by agencies such as Tinsa or other property valuation companies. A second group includes indices based on sale prices, such as those prepared by the INE or private entities, such as Tecnocasa. This group of indicators can also include data from contracts signed at the land register. An additional feature of the latter group is that, for the past few years, they have allowed for corrections using the Case-Schiller method. Specifically, the index is calculated on the basis of the repeat sales method, which uses data on homes that have been sold at least twice to calculate the rise in value of properties with constant characteristics. The problem, however, is that the prices officially recorded are not necessarily the same as those agreed upon in private. Thirdly, there are indices based on offered prices, particularly those produced by web portals publishing private sellers’ offers, such as Idealista or Fotocasa.

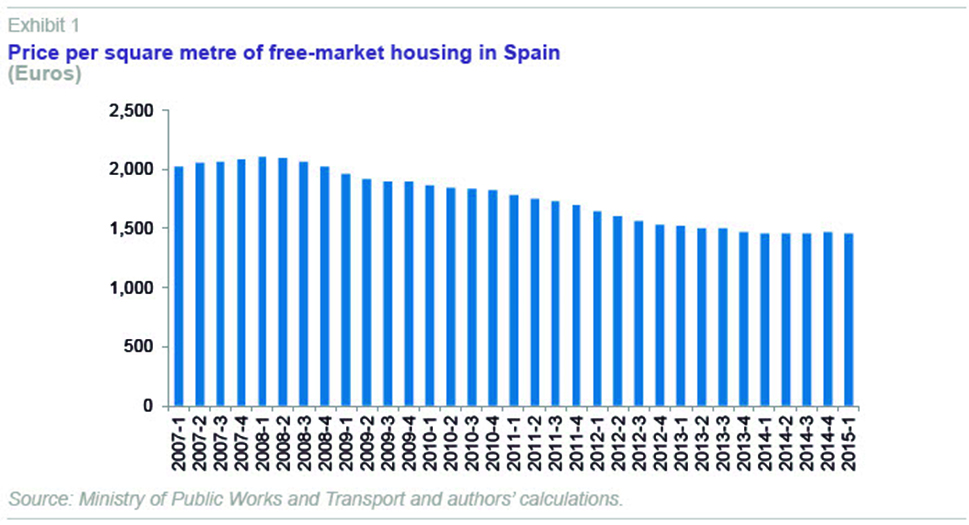

As an initial reference, Exhibit 1 shows the change in the value of an average square metre of housing in Spain, according to Ministry of Public Works and Transport data. The latest available data put the price at 1,457 euros per square metre in the first quarter of 2015, down 0.1% from the first quarter of 2014. The cumulative drop since the first quarter of 2008 –when, according to these data, the price increase peaked– is 30.1%. The data suggest that most of the adjustment has taken place, but do not offer any evidence of a significant or sustained recovery in prices.

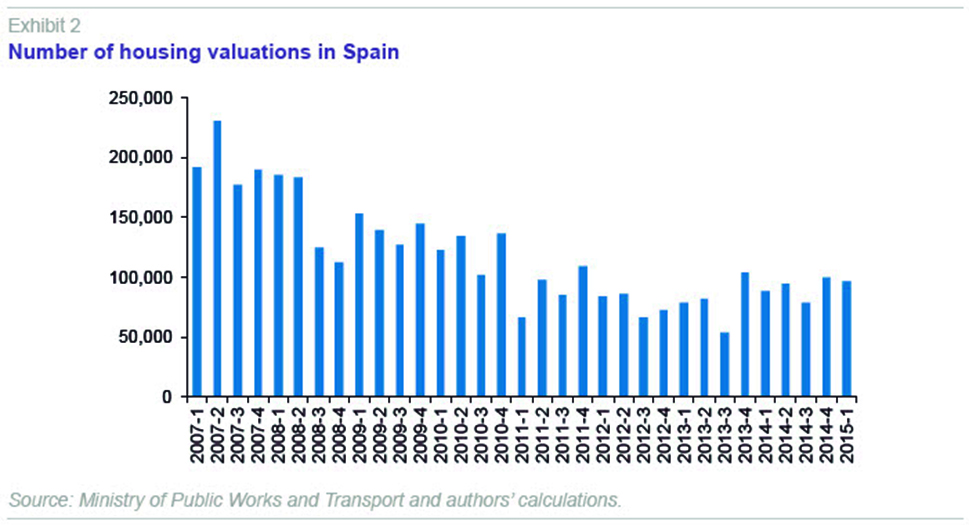

The Ministry of Public Works and Transport data are based on surveyors’ valuations. That said, the evolution of housing prices over the last few years has been influenced to some extent by speculation over the future tax treatment of homes, mortgage renegotiations and other legal issues, which are discussed throughout this issue of Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook (SEFO). As Exhibit 2 shows, the number of valuations has increased in the last few quarters, stabilising at around 100,000 valuations per quarter. However, in 2007 and 2008, when prices were still at their peak, there were almost twice as many valuations (around 200,000 per quarter).

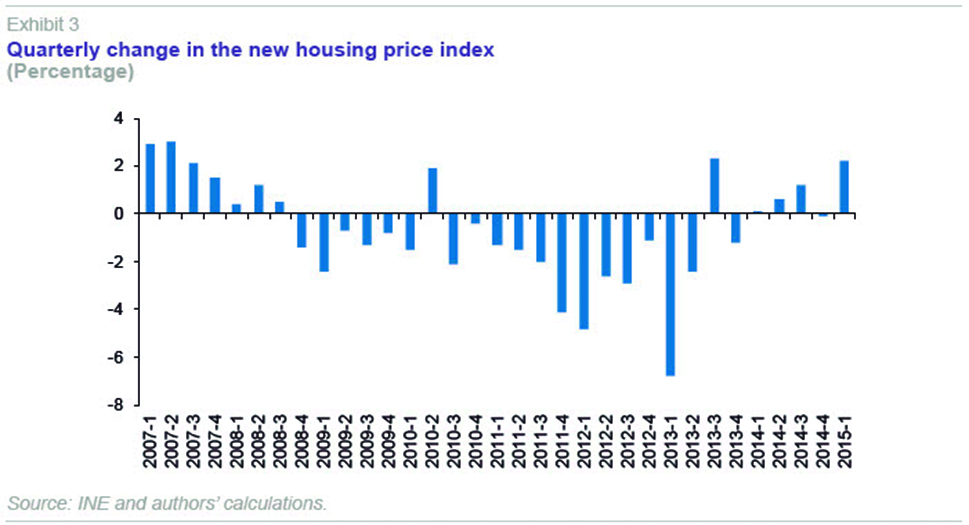

If we look at sales rather than valuations (e.g., the INE price index, whose quarter-on-quarter changes are shown in Exhibit 3), recent progress has been uneven. Thus, there was an increase of 2.2% in the first quarter of 2015, after a drop of 0.1% in the last quarter of 2014. Prices went up 4.2% in the second quarter of 2015, the largest rise in eight years.

Some more recent indicators subsequent to the first and second quarter suggest that what has been happening to prices recently is more of a stabilisation than a true or continuous recovery. But there is some disagreement. For example, the College of Property Registrars has reported that housing prices rose by 5.1% on a year-on-year basis in the second quarter of 2015 (with a rise of 2.65% in the first quarter). However, according to the real estate website Idealista, the price of second-hand homes in Spain dropped by 0.6% in the month of August, to an average of 1,577 euros per square metre. However, on this point it also has to be borne in mind that there are numerous local markets that are evolving differently. Thus, taking Idealista’s data for August, the month’s biggest price rises took place in La Rioja (0.7%), Castile-La Mancha (0.2%), Madrid (0.2%) and Navarre (0.1%). In Andalusia and Castile-Leon there was no change, and in the other 11 regions prices fell, particularly in Aragon (-1.4%), Murcia (-1.2%) and Cantabria (-0.6%).

The appraiser Tinsa suggests that the drop in prices in August was even bigger, at 0.9% on a year-on-year basis, and indicates that the adjustment since the first quarter of 2008 –where it situates the peak– has been 41.8%. Tinsa also distinguishes between geographical areas, indicating that prices fell by an average of 1.3% on the Mediterranean coast, but that the biggest drop was in metropolitan areas (-4%). Although the major Spanish cities were an exception, falling prices in urban areas suggest that the adjustment is still continuing in much of the country, although it may be bottoming out.

Transactions and their financing

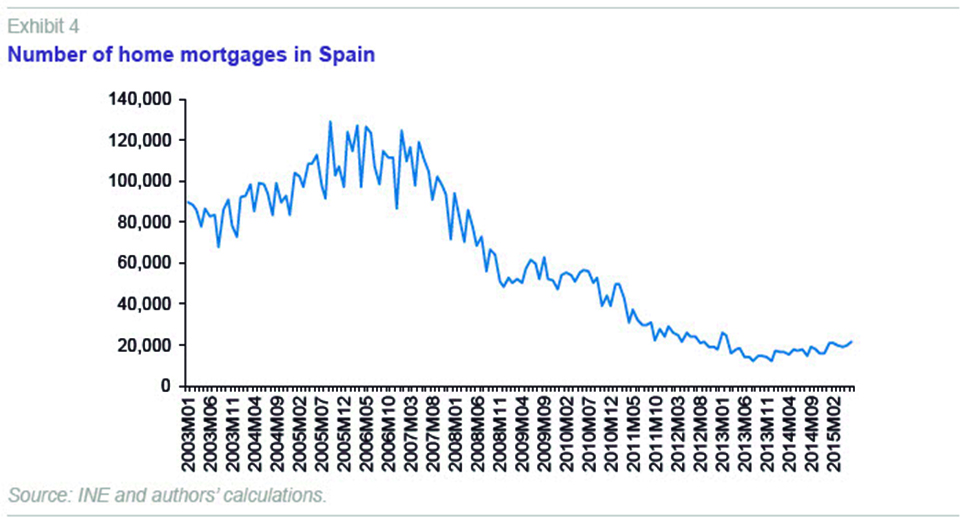

Another interesting comparison between the pre-crisis and current environment in the property market relates to transactions and how they are financed. Over extension of credit has been identified as one of the main mechanism by which the pre-crisis asset bubble was generated. Thus, recent news of a recovery in the mortgage market has, at times, caused an overreaction about its potential negative impact, with fears of there being excessive demand for mortgages without proper regard for the risk. However, recent figures do not offer any evidence to substantiate these concerns. Exhibit 4 shows the change in the number of mortgages on homes in Spain. In June 2015, the figure was 21,454, 20.6% more than in June 2014. Even though this increase is significant, once again it is the low starting point for the comparison that makes the increment appear bigger. Indeed, looking at Exhibit 4, it can be seen that in 2005 and 2006, the number of mortgages issued was significantly more than 100,000 a month.

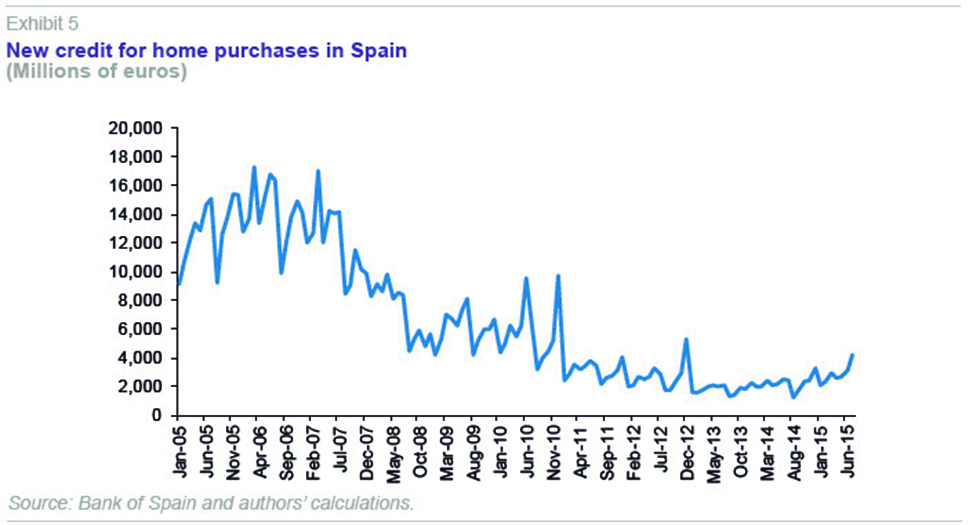

A similar trend can be seen in the data published by the Bank of Spain on the flow of new lending for home purchases (Exhibit 5). Comparing the data for July 2015 (4,227 million euros) with that for July 2014 (2,467 million euros) there has been an increase of 71.3% in monthly new financing in this month from one year to the next, but as in the previous comparisons, the figures are relatively modest. In 2005 and 2006, monthly lending for housing was in the 13 to 17 billion euro range.

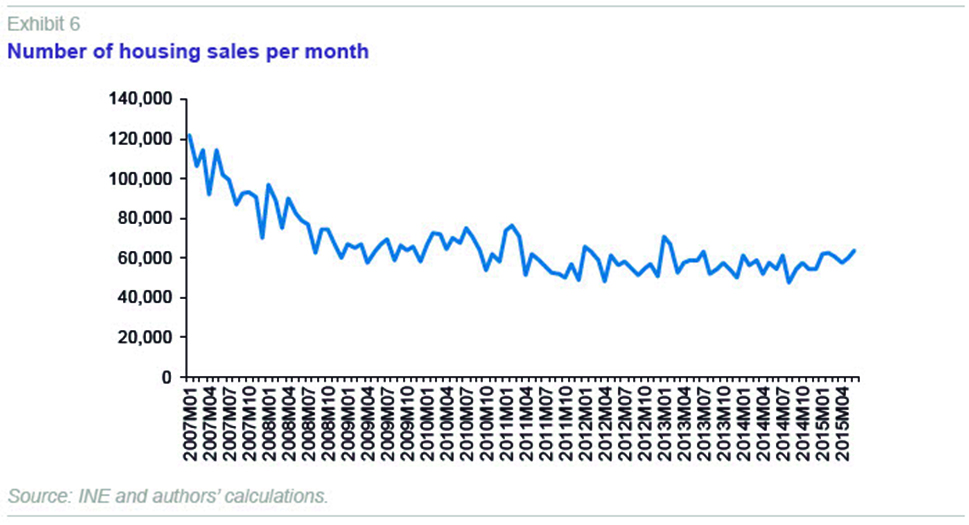

Housing sales also show more of a stabilisation than sustained growth (Exhibit 6). According to the INE, there were 67,041 housing sales in July 2015 (transfers of property ownership), up 10.2% on that in July 2014 (54,277 transactions) However, these figures are still a long way from the 121,687 transactions in January 2007, while the market was booming.

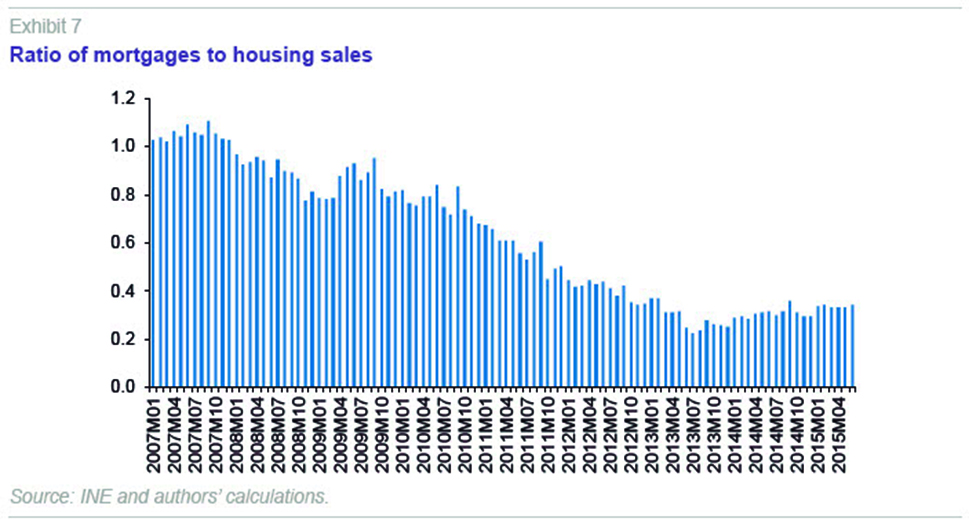

Comparing the number of new mortgages to the number of homes sold (as shown in Exhibit 7) offers an interesting insight into the nature of these transactions. In the pre-crisis years, the ratio of mortgages to homes sold was close to, or even above, unity, suggesting that mortgage borrowing was being used to finance more than just property purchases. However, this ratio has declined considerably, reaching a minimum of 0.22 in July 2013 and standing at 0.34 in June 2015 (most recent data available). This means that a substantial portion of home purchases in recent years has been paid in cash, and it is likely that many of these purchases are being carried out by specialist investors rather than households.

Conclusion

As a whole, the data analysed here suggest that the Spanish property market has entered a phase of stabilisation. In addition, recent statistics points towards a normalisation that includes a bigger contribution from construction in line with its natural share of the country’s production structure. This process will also be gradual, as financing of demand is conditional upon the deleveraging of the economy and is constrained by the very high unemployment rate, which significantly raises credit risk.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and FUNCAS

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and FUNCAS