The 2016 General State Budget: Balancing fiscal consolidation and the electoral cycle

The 2016 budget envisions deficit reduction at the central government level in line with the 2015-2018 Stability Programme, but budget implementation for the first half of 2015 anticipates the overall general government deficit will slightly deviate from the target. In any event, existing fiscal pressures at the regional level and on the social security system highlight the need for exploring new funding mechanisms.

Abstract: The 2016 General State Budget (PGE2016) seeks to balance fiscal consolidation with typical pre-election budgetary measures. However, modifications to the budget are possible if the general elections bring a change in government. A slight drop in public expenditure, in conjunction with a rise in revenues, would enable the central government deficit to be brought down in line with the foreseen objectives. Nonetheless, budget implementation in the first half of 2015 seems to anticipate a combined general government deficit that slightly deviates from the target. Once again, the autonomous regions emerge as the most disruptive factor, although the most recent deviations in the case of the social security system and the medium-to-long term demographic trends make it necessary to consider new funding mechanisms.

The 2016 General State Budget (PGE 2016) is the first since the transition to democracy to have been significantly brought forward (by a quarter). This fact and the government’s decision to govern right up until the end of the legislative period, with general elections in December 2015, have shaped and determined the content of both the political debate and of the budget itself. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, the incumbent is obliged to match necessary fiscal consolidation with budgetary measures that boost its popularity, against the backdrop of a scenario in which the opinion polls suggest it will be impossible for the government to win another absolute majority in the Congress of Deputies, making substantial loss of electoral support look likely. Secondly, if there is a change of government, the PGE2016 could be significantly modified as early as the first quarter of next year. While the first point detracts from the credibility of balancing income and expenditure, the second raises uncertainty as to budget implementation. On the other hand, the sharp acceleration in economic growth in 2015 and 2016 will help balance the accounts and make the deficit targets more feasible.

This article is sub-divided into three sections. The following section gives an overview of the budget’s key figures and examines their consistency. The second section analyses how the budget fits into the 2015-2018 Stability Programme for the Kingdom of Spain. Finally, the article identifies certain critical factors for budget execution, and in general, for compliance with the public deficit targets set for the general government as a whole.

The budget’s key figures

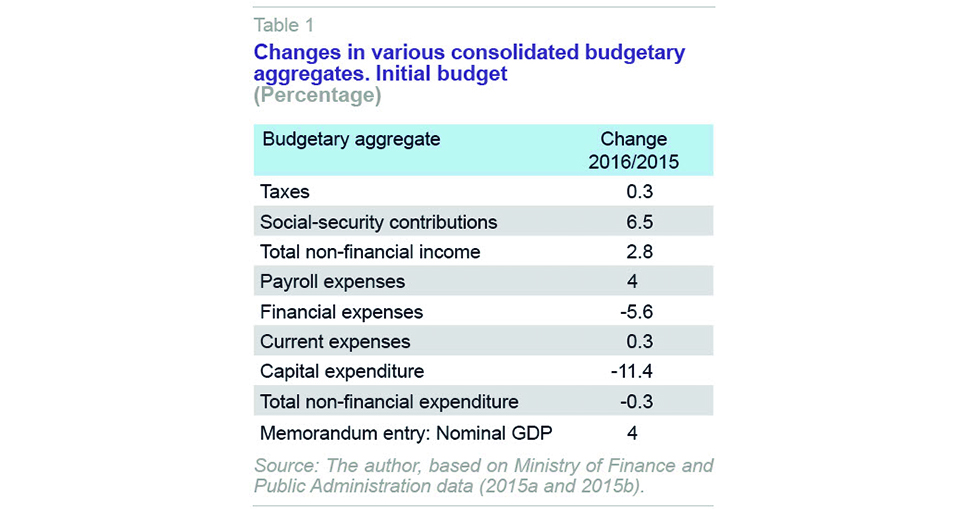

Table 1 shows the percentage changes in various public expenditure and revenue items.

[1] The figures refer to the consolidated central government budget, which includes the social security system and a part of the autonomous regions’ and local authorities’ budgets, associated with the various intergovernmental grant programs. Regional revenues from totally or partially devolved taxes (VAT, income tax, excise duties) collected by the National Tax Administration Agency (AEAT) are not included. Relative to GDP, budgeted non-financial expenditure (314.49 billion euros) is equivalent to 27.5% of Spain’s GDP and accounts for slightly more than half of public expenditure, after discounting transfers to sub-national levels of government, to avoid problems of double counting. Therefore, although it is true that this leaves out a substantial part of the Spanish public sector, the PGE2016 allows us to approximate the overall budgetary dynamics and their consistency with the total public deficit target.

The budget is not expansionary. Quite the opposite. With nominal GDP growth of 4% envisaged (3% real growth and 1.1% from the GDP deflator), total non-financial expenditure will drop by 0.3%, due to a combination of a sharp drop in capital spending (-11.4%) and a slight rise in current expenditure (0.3%). What stands out in the case of the latter is the increase in workers’ wages (4%), due to projected pay increases of 1%, the disbursement of the remaining half of public sector employees’ extraordinary payments withheld in 2012, and an increase in the rate at which civil servants are replaced. For their part, interest payments will drop considerably (-5.6%) as a consequence of lower rates on new debt issues. On the revenue side, there is a contrast between the slight rise in tax collection projected (0.3%) and the expected stronger growth in social security contributions (6.5%). The split between the trend in central government revenues and those collected by the tax collection agency (AEAT), rising by 4%, also stands out. The explanation cannot be found in the corporate tax, which exclusively accrues to the central government, and is set to grow by 5.5%. The tax cuts passed by the central government and already implemented could be an explanatory factor, but not the only one. As Lago-Peñas (2015b) points out, opting for an income forecast at the lower end of the confidence interval could indicate future tax cuts not expressly included in the PGE2016. The remarks made by the Finance Minister when presenting the budget support this hypothesis.

[2]

Overall, non-financial income is set to rise by 2.8%, significantly less than nominal GDP, but substantially more than expenditure. As a result, the central government public deficit will be cut by the amount envisaged in the 2015-2018 Stability Programme, from 2.9% to 2.2% of GDP. In short, the popular measures aimed at the general public (such as the income tax cut) or targeting particular groups (for example, wage increases and other benefits for public-sector employees), are made to fit in with the budget so that the overall contractionary stance of fiscal policy is maintained, the deficit targets are met and spending relative to GDP remains on a rapid downward trend.

The PGE2016 and the 2015-2018 Stability Programme

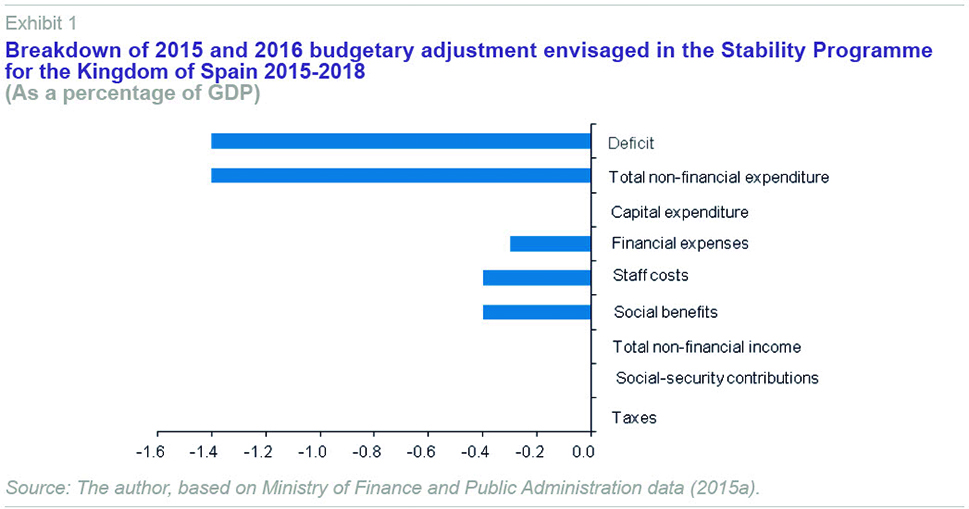

Although we have already mentioned that the PGE2016 complies with the central government deficit targets contained in the scenario envisioned in the 2015-2018 Stability Programme, it is interesting to analyse whether the path is that envisaged or if there are significant deviations, bearing in mind that the PGE2016 does not include the budgets for sub-national levels of government. Exhibit 1 includes the expected change in various public income and expenditure aggregates between 2015 and 2016. The estimated deficit reduction is of 1.4% of GDP, falling exclusively on the expenditure side. Both taxes and social security contributions will remain stable as a share of GDP. The two main items undergoing adjustment would be staff costs and social benefits, which would each drop by 0.4 percentage points. In the case of the latter, the main explanation lies in the decrease in unemployment benefits, due to the falling unemployment rate and end of benefit pay-out. The third most significant items for the downward adjustment would be debt interest (-0.3%); capital expenditure remains unchanged, and the remaining 0.3% would be explained by current spending’s growing more slowly than nominal GDP.

Comparing Exhibit 1 with Table 1, the overall non-financial income and expenses match. With nominal GDP growth of 4%, the non-financial expenses drop and the non-financial income rises by close to 3%. Bearing in mind the point mentioned regarding the taxes managed by the AEAT for sub-national treasuries, the projected growth in general government income will be close to this 4%. The debt interest item also fits in. Social security contributions will increase as a share of GDP if the government’s forecasts are met. Where the deviations from the published figures are biggest is in capital expenditure and the remuneration of public-sector employees. While growth in the latter should be similar to that of GDP, the PGE2016 envisages a substantial drop in capital expenditure. Investments and capital transfers will decrease by 11.4%. And, in the opposite direction, against a marked drop in the weight of staff costs envisaged in the 2015-2018 Stability Programme, the central government envisages this item growing at a similar rate to nominal GDP in 2016. Although it is true that public-sector employment in sub-national levels of government is larger in volume, and it remains to be seen what decisions will be taken, the signal sent by PGE2016 is clearly expansionary.

The staff cost reduction targets in the 2015-2018 Stability Programme are probably excessive and difficult to reconcile with maintaining quality public services, above all without a thorough civil service reform that reallocates resources and improves incentives. However, compensating for the planned wage increases with additional cuts in public investment, which has already suffered severe and repeated cutbacks since 2010, also raises medium and long-term challenges for the fundamentals of the Spanish economy. Revision of the Stability Programme seems unavoidable, at least on this point.

On budget implementation: Forecasts for 2015 and outlook for 2016

The macroeconomic scenario for compliance with the 2016 deficit targets is favourable. The government’s forecasts for 2015 and the coming year are in line with those of international organisations and official and private entities in Spain and independent Spanish public bodies consider them reasonable (Bank of Spain, 2015; AIReF, 2015b). This is particularly so given the acceleration in GDP growth, in those cases where the revisions are more recent. As Table 2 shows, real GDP growth in 2015 (3.3%) is similar to Funcas’ latest estimate and the Funcas consensus forecast (3.2%) and close to the figure given by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Bank of Spain. For 2016 the differences are similar, and only the IMF and the European Commission (2.5% and 2.6%, respectively) deviate significantly from the government’s estimate of 3%. However, once again, it is to be expected that the difference will become narrower when the figures are revised in the third quarter of 2015. This real GDP growth and increase in the GDP deflator of 0.5% in 2015, and of 1.1% in 2016, will help compliance with the targets through its positive effect on automatic stabilisers (such as unemployment insurance), on tax collection and social security contributions (although to a lesser extent, as we shall see below) and on the denominator of the public deficit and debt objectives, which are expressed as a percentage of GDP.

Nevertheless, this clearly positive component is accompanied by other factors that give rise to doubts and uncertainties. First, the closing of the current fiscal year. Second, the conduct and budgetary control of sub-national levels of government and the social security system. And third, the possibility of a change in government as a consequence of the general elections in December.

Doubts exist as to the fulfilment of the deficit targets for 2015 and, consequently, as to the scale of the adjustment in 2016 to achieve the deficit commitment for that year. In this case, the fundamental reference is AIReF’s (2015a) report on expected compliance. In short, it will be extremely difficult to meet the 2015 deficit target. Basically, things are turning out as expected (Lago-Peñas, 2014). A substantial number of regional governments are set to deviate from their targets for 2015, such that the deviation for the subsector as a whole could end up at around half a percentage point. Fortunately, local authorities will achieve a surplus of the same order of magnitude, rather than the equilibrium set as their target, which will offset the worse performance by the autonomous regions. In the case of the social security system, the possibility of non-compliance is also projected, estimated at around four tenths of a percent, which cannot be offset by the central government, which will comply with its obligations, but without offering a margin of security to other sub-sectors. The poor outlook for the social security system arises from over-optimism about the results of changing the system for managing contribution payments and the measures to create incentives for affiliation, which reduce the collection elasticity of new jobs. Finally, the financial buffer envisaged in the central government’s financial accounts thanks to the acceleration of economic activity, has been narrowed by various measures put into practice since the budget’s approval.

Specifically, AIReF (2015a) estimates that the joint effect of the measures to support sub-national governments (Fondo de Liquidez Autonómica [Regional Liquidity Fund] and the Fondo de Financiación de Pagos a Proveedores [Supplier Payments Financing Fund]), bringing forward the income-tax reform planned for 2016 to July 2015, the final settlement of the financing of the autonomous regions for 2013 and a smaller than expected quota and financial compensation from the Basque Country will reduce the central government’s revenues by around five tenths of a percentage point. In short, extrapolating from what has been seen in the first half of the year would situate the overall deficit around 4.6%, which is slightly above the Funcas’ consensus in September 2015 and the most recent forecast available from the European Commission (4.5%). In any event, it should be noted that AIReF itself, at the presentation of its report, warned that the deviation is not inevitable, provided that budget execution by the four sub-sectors in what remains of 2015 is better than average and remains in the most favourable part of the confidence interval estimated by the organisation.

Secondly, there is broad convergence over the assessment that there is a problem at the autonomous region level. The international organisations agree on this point as one of the most disruptive factors to fiscal stability in Spain (IMF, 2015; European Commission, 2015). In this sense, Spain is an interesting case to study given the high degree of budgetary decentralisation and the depth and duration of the recession, which has subjected the public finances to a severe stress test. In fact, a variety of different formulas have been tried out over the last seven years (Lago-Peñas, 2015a). These have ranged from the laissez-faire of the early years of the crisis, to the tightening of legislation in 2012, which was interpreted –not without some justification–as a move towards recentralisation, but which was accompanied by a clear improvement in compliance with the deficit targets in 2012 and 2013, allowing for the renunciation of legislative mechanisms available and the introduction of extraordinary financing mechanisms, softening regional budgetary restrictions. It will probably be necessary to find a new solution based on a four-pronged approach. First, to allow the autonomous regions a larger share of the deficit, which is justified in view of the competencies they have acquired, and the size of their budgets. What makes little sense is to aim for demanding cut-backs and systematically fail to meet them. Second, to reform the regional financing system so as to make the regions’ income more autonomous, but also significantly harden regional budget constraints. Extraordinary liquidity mechanisms, which are detrimental to achieving this rigidity, should be rolled back as the economic situation normalises. Third, revise the budgetary stability regulations to eliminate supervision, control and penalty mechanisms that are not applicable from an economic policy perspective. Fourth, apply mechanisms to ensure the legislation is followed automatically and rigorously.

In addition to the above, the most recent deviations in the case of the social security system and the medium-to-long term demographic outlook make it necessary to think about exploring financing mechanisms drawing on the PGE, as AIReF (2015b) recommends. It is also worth noting that the figure for the expansion of social security contributions envisaged for 2016 might be excessive, particularly if the starting point turns out to be a long way short of that budgeted in 2015. On this point the government has just raised the possibility that certain pensions (survivors’ and orphans’ pensions) be financed via taxes, a solution that had already been put on the table by the trade union Comisiones Obreras during the debate on the recent reform to the pensions system. Whether it is this or some other mechanism that is introduced, such as the special-purpose tax proposed by the Socialist Party (PSOE) during the current budget debate, the Toledo Pact should deal with the issue in the coming legislative period.

Finally, the possibility of a change of government in the coming months merits consideration. The available voting intentions surveys suggest a sharp drop in votes for the two main parties (the People’s Party and the Socialist Party) and the rise of two new parties (Podemos and Ciudadanos). Specifically, the Centre for Sociological Research (CIS) highlights that the two traditional parties have been able to attract around 80% of votes over the course of the series, but that this figure has dropped to 50% in the last year, benefiting the two new players on the political stage. Although this scenario may change over the coming months, the likelihood of an absolute majority appears limited. A weak minority government or a coalition seem more likely, bringing concessions and pacts that may significantly alter both the PGE2016, which is still at the early stages of implementation, and the fiscal Stability Programme over what is left of the decade. Even assuming that the debt and deficit targets agreed with Brussels are met, it is to be expected that the combination of income and expenditure and the composition of both sides of the budget will be modified.

Notes

For a detailed analysis of the PGE2016, see the article by Romero-Jordán and Sanz-Sanz (2015) in this issue.

References

AIReF (2015a), Informe de cumplimiento esperado de los objetivos de estabilidad presupuestaria, deuda pública y regla de gasto 2015 de las Administraciones Públicas, 17-7-2015.

— (2015b), Informe sobre las previsiones macroeconómicas del Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales del Estado 2016, 29-7-2015.

BANK OF SPAIN (2015), Comparecencia ante la Comisión de Presupuestos del Congreso de los Diputados en relación con el Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales del Estado para 2016, Banco de España, 18-8-2015.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2015), Council Recommendation on the 2015 National Reform Programme of Spain and delivering a Council opinion on the 2015 Stability Programme of Spain, 15-5-2015.

IMF (2015), Spain: Article IV Consultation. Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Spain, 14-8-2015.

LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2014), “Spain’s draft 2015 General Budget: Balancing constraints and credibility,” Spanish Economic and Financial OutlooK, Vol., 3(6): 65-71.

— (2015a), “Remaining challenges to budgetary stability in Spain,” Spanish Economic and Financial OutlooK, Vol., 4(2): 67-74.

— (2015b), “Estabilidad fiscal: ¿será suficiente con la mejora de la coyuntura económica?,” Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 4(4): 47-54.

MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION [MINISTERIO DE HACIENDA y ADMINISTRACIONES PÚBLICAS] (2015a), Actualización del Programa de Estabilidad del Reino de España 2015-2018.

— (2015b), Proyecto Presupuestos Generales del Estado 2016 [Draft General State Budget 2016].

ROMERO-JORDÁN, D., and J. F. SANZ-SANZ (2015), Spanish Economic and financial outlook, Vol. 4(5).

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of GEN, University of Vigo.