Spanish mortgage market: Court rulings´ implications for regulation

Spanish households’ large exposure to mortgage debt prompted a series of regulatory initiatives in an attempt to mitigate certain negative aspects of Spanish mortgage law, such as eviction proceedings and the so-called mortgage ‘floor causes’. In most instances, precedents established by both Spanish and European courts have had an impact on fostering regulatory changes in favour of borrowers´ rights.

Abstract: The mortgage act reform of 2013, on measures to reinforce protection of mortgagors, factored in prior court decisions on evictions and ‘floor clauses’ embedded into mortgage agreements. In the case of evictions, court hearings to determine the existence of unfair terms in such agreements were given the power to suspend foreclosure proceedings and halt ongoing evictions. In the case of floor-rate clauses, subsequent to a decision by the Spanish Supreme Court, a series of new requirements were introduced to mortgage arrangement processes with a view to protecting the borrower and ensuring full familiarity with agreed-upon terms. In contrast to the sequence of events as regards other areas of regulation, these recent measures affecting Spanish mortgage regulation were adopted in response to court rulings and not as a precursor to them.

Introduction

Over the course of the last few years, several aspects of Spanish mortgage law have been questioned before the Spanish and European courts. However, the two most important, on account of their social, economic and regulatory ramifications, are probably eviction proceedings and the so-called ‘floor clauses’. Court rulings in some of these cases have been of such significance that they have led to mortgage law reforms and other complimentary regulatory changes designed, among other things, to comply with these court sentences.

Alongside the regulatory changes introduced by the 2013 mortgage act, other changes include the limitation on the repayment period of mortgages included in the qualifying portfolio or the guaranteed independence of valuation firms (Romero, 2013). However, as these changes were not explicitly made in direct response to court rulings, they will not be examined in this article.

This article briefly overviews the scale of each of those issues, evictions and ‘floor clauses’, which have been deliberated in some of the most important court rulings to date and their impact on Spanish mortgage law.

Evictions

Spanish households’ high levels of indebtedness have often been highlighted as one of the Spanish economy’s greatest imbalances. The ratio of gross household debt to disposable income surpassed 130% in 2007, one of the highest levels in Europe. Although this ratio has since come down, it still stood at well over 100% of disposable gross income at year-end 2014.

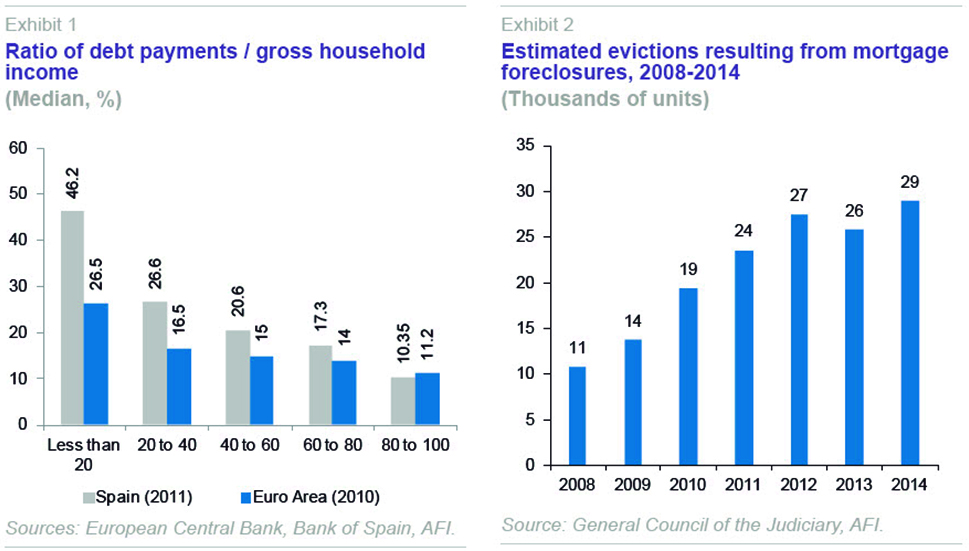

Focusing the analysis on the ability to pay off the debt more than on the aggregate amount of debt per se, the picture in Spain is still worse relative to neighbouring countries, as revealed by the European Central Bank study on European household borrowing, using data from 2010 and 2011. Specifically, the ratio of debt payments to gross income stood at 18.0% in Spain compared to the eurozone average of 13.9%.

The difference was even more pronounced in the case of lower-income households (measured as those falling within the 20th percentile of income distribution). In this percentile, the debt burden in Spain rose to 46.2% in 2011, compared to the eurozone average of 26.5% in 2010.

This high level of Spanish household indebtedness, against the backdrop of a crisis that drove a sharp rise in unemployment, was one of the key factors behind the growing incidence of house evictions. According to the General Council of the Judiciary, over 600,000 foreclosures were set in motion between 2007 and 2014, with one quarter of these resulting in the eviction of the debtors. It is worth noting that this statistic does not take into account whether the property is rural or urban, nor whether it is a dwelling.

In the case of households, the intensification of the crisis in Spain in 2011 further accelerated the volume of non-performing loans and, consequently, the pace of evictions, which is why most of the legal initiatives and proceedings attempting to bring them to a halt were concentrated in that year.

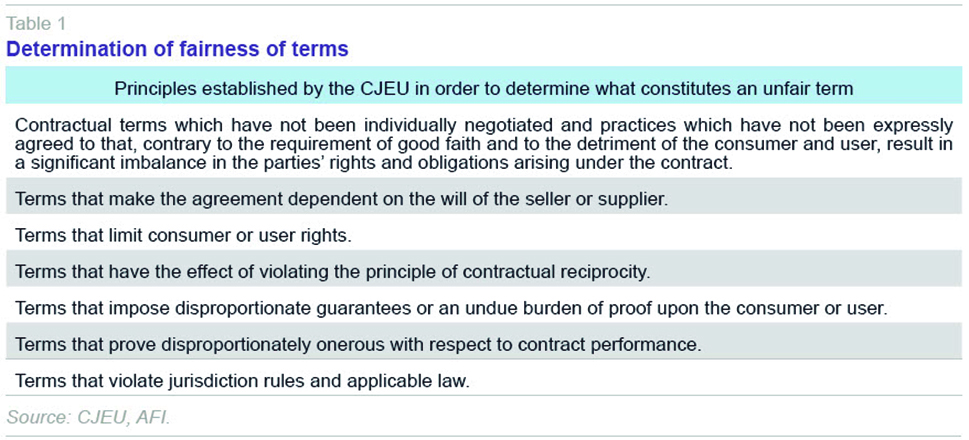

The first court ruling on evictions was in early 2013 and came at the highest level, specifically the Court of Justice of the European Union (hereinafter, CJEU). THE CJEU´s ruling marked a watershed event for Spanish mortgage law as it determined that certain aspects of the then-prevailing regulations were not compatible with Directive 93/13/EEC of the Council of April 5th, 1993, on unfair terms in consumer contracts.

Firstly, it gave judges examining whether a mortgage contract contains unfair terms the power to issue an injunction against foreclosure proceedings and prevent the related eviction. Secondly, it set a series of principles governing how judges should interpret what constitutes an unfair term (see Table 1 below). And thirdly and lastly, the ruling requires these judges to compare the default interest being charged by the lender bank in question with the statutory rate of interest in order to determine its appropriateness in terms of bringing about the objectives sought by the late-payment charges themselves.

The Spanish government responded swiftly and in just three months had drafted and passed a new law with amendments to different regulations to bring them in line with the CJEU’s ruling and findings. Some of the most important structural changes introduced by Spanish Law

[1] 1/2013 include:

- Additional powers were granted to judges and notaries by empowering them to halt mortgage enforcement proceedings and suspend out-of-court sales of foreclosed assets in cases in which the related mortgage agreements were found to include unfair terms.

- The rate of default interest on principal residences was capped at three times the statutory rate of interest. This had the effect of capping the rate at 12%, compared to rates of 20% or more that some of the banks had been charging, and of facilitating the repayment of outstanding debts. Capitalisation of default interest was also outlawed.

Impact

Thanks to the initial legislative reforms and the temporary paralysis of evictions for the most vulnerable groups in society

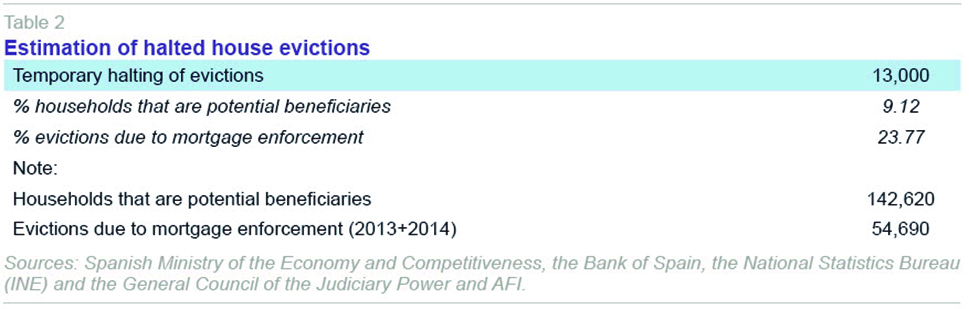

[2] championed by the central government, the rise in the initiation of foreclosure proceedings witnessed in recent years has been stemmed. Between June 2013 and December 2014, some 13,000 evictions have been halted; this figure represents 24% of all evictions arising from mortgage enforcement proceedings. In terms of the government’s initiative for the socially vulnerable, the number of related evictions halted accounts for 9.1% of the total.

Despite these results, the eviction issue remains high on the economic and social agenda. For this reason, and with the aim of solving the housing need faced by evicted families, various regional administrations

[3] have been passing laws that follow a similar pattern: introduction of the compulsory expropriation of the right to use vacated dwellings foreclosed on by the banks, their real estate subsidiaries and real estate asset management companies (including SAREB, Spain’s so-called bad bank) for a certain period of time on the grounds of special social emergency circumstances.

The international authorities, against the backdrop of their supervisory remit under the European Stability Mechanism (“ESM”), have expressed their concern regarding the potential impact on the Spanish financial system of regional mortgage holder protection regulations such as these. The state government appealed them before the Constitutional Court, which immediately issued an injunction against some of their terms. To date this tribunal has outlawed some of these terms, making the following arguments:

- Determination that it is illegal to expropriate vacant homes owned by the banks.

- Invasion of the state’s exclusive power to ‘coordinate general planning of the country’s economic activity’.

- Rendering ineffective the measures introduced by the state government, particularly those related to bank restructuring and home-owner protection.

As a result, the Constitutional Court ruling has the effect of curtailing development of these kinds of regional initiatives and preventing, by extension, the potential adverse effects for the banking system in particular and the Spanish economy in general.

‘Floor clauses’

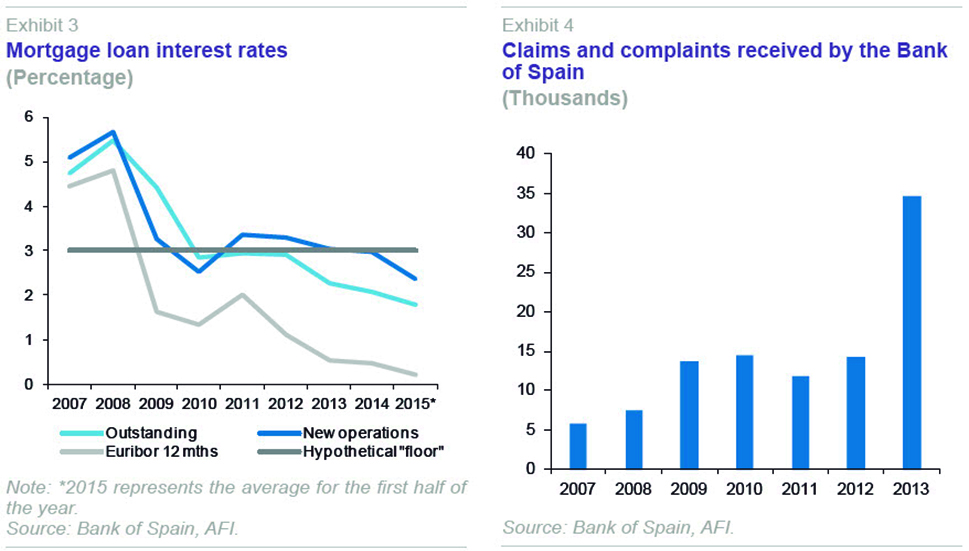

Besides evictions, the other area of mortgage legislation that has resulted in many court hearings is that of the so-called ‘floor clauses’, which establish a minimum rate of interest in floating-rate mortgage loans, such that borrowers are prevented from benefitting from declines in the agreed-upon benchmark rate. The initiatives taken against these clauses intensified as benchmark rates (mainly 12-month Euribor) tumbled, bottoming out at around 0.20%, a level at which they have remained for many months.

According to the School of Property Registrars, over 90% of the new mortgages taken out in Spain were arranged at floating interest rates and were benchmarked against the 12-month Euribor. The drastic drop in this interest rate since 2009 unveiled the existence of ‘floor clauses’ in some of the mortgages arranged beforehand. According to a study compiled by the Bank of Spain at the request of the Senate in 2010,

[4] close to 30% of the mortgage portfolio outstanding at the end of 2009 contained clauses of this nature and the average ‘floor’ rate was around 3%.

The fact that indebted households were being prevented from benefitting from the drop in benchmark rates, coupled with increasing difficulties in servicing their debts as a result of growing unemployment, had the effect of doubling the number of claims and complaints received by the Bank of Spain and marked the start of a proliferation of court cases.

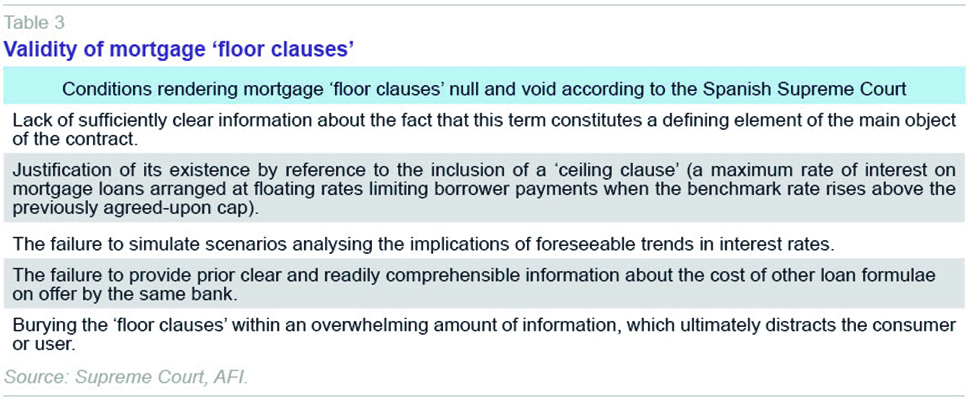

In addition to the CJEU court ruling of early 2013 on unfair terms in general (analysed above), Spain’s Supreme Court, in the case of Ausbanc against certain banks, declared the mortgage ‘floor clauses’ null and void on the basis that they breached certain contractual requirements. In fact, the Supreme Court introduced criteria designed to serve as a guide for determining when these clauses should be declared null and void (see Table 3).

Through Law 1/2013, the central government introduced a series of changes designed to cater to the Supreme Court’s findings with respect to the so-called ‘floor clauses’:

- It made mandatory the inclusion in the public mortgage deed, alongside the customer’s signature, a handwritten statement by which the borrower warrants that he or she has been adequately warned of the potential risks under the mortgage loan agreement, insofar as the said agreement:

- establishes floors or caps with respect to exposure to the movement in benchmark interest rates;

- comes with the requirement to arrange an interest rate hedging instrument; and

- is granted in one or more foreign currencies.

In this manner, the financial conditions of the borrower and his or her full familiarity with the terms of the mortgage loan agreement are set down in writing.

- The court further asked the Bank of Spain to prepare and distribute a manual on bank loans in order to contribute to bank service transparency and customer protection. Among other things, this manual addresses ‘floor clauses’. This official mortgage user guide was published two months after the law was passed and has been available for download since then from the Bank of Spain’s website. [5]

Impact

This Supreme Court ruling meant that the banks affected by it had to eliminate these ‘floor clauses’ from their mortgage books; however, it did not apply on a widespread basis to the entire banking system nor did it apply retroactively to other court rulings issued or payments already made. However, it did set a precedent for future claims. This is evidenced by the fact that that same year (2013), the number of claims and complaints received by the Bank of Spain exceeded 34,600, more than twice the number received the prior year and the largest annual number received to date. Some 53.1% of these complaints and claims related to ‘floor clauses’ and the Bank of Spain’s Department of Market Conduct and Claims upheld the claimant’s case over 80% of the time.

Conclusions

In other areas of regulation, the courts have had no influence at all on regulatory design, and only once legislation has been passed and implemented have they clearly backed one party or another, at times potentially reducing its efficacy. In the case of mortgages, new legislation has taken into account court rulings challenging the regulations existing up until the start of the crisis, generally because it failed to comply with regulation at the supranational level. It is therefore not expected that the courts will take a discretionary attitude following the entry into force of recent measures.

On the evictions front, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled in early 2013 that judges investigating the existence of unfair terms in mortgage agreements had the power to suspend foreclosure proceedings and halt ongoing evictions. Law 1/2013 transposed this ruling into Spanish law. On the other hand, the legislation passed recently by certain regional governments has not prospered as the Constitutional Court has ruled the compulsory expropriation of vacant dwellings in the hands of the banks contemplated in these measures illegal.

As for the ‘floor clauses’ included by some banks in their mortgage agreements, the Supreme Court ruled them null and void in 2013; however, this ruling did not apply to all the banks or retroactively to other case law or payments already satisfied. Law 1/2013 introduced new mortgage arrangement requirements and called on the Bank of Spain to publish a mortgage user guide in order to foster transparency and protect banking service users.

Notes

For more information on the other regulatory changes introduced by Law 1/2013, see Romero (2013).

Spanish Royal Decree-Law 27/2012 on urgent measures designed to protect mortgage holders was initially introduced with a two-year term but has since been extended for a further two years so that it will now apply for four years. Further information is available at the following link:

http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2015/02/28/pdfs/BOE-A-2015-2109.pdf

To date, and in chronological order, such measures have been passed in Andalusia (Law 4/2013), Navarra (Regional Law 24/2013) and the Canary Islands (Law 2/2014).

References

ROMERO, M. (2013), “Un análisis de la reforma hipotecaria”, Revista Análisis Afi, 1º semestre 2013: 17-21.

María Romero and Ángel Berges. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.