Limited impact of the global slowdown on growth expectations

Latest data for the second quarter confirm the continued strength of the Spanish recovery, although somewhat below expectations. Slight downward revisions to the 2016 forecast reflect a worsening global economic climate.

Abstract: The outlook for the global economy has recently deteriorated as a result of the slowdown in the Chinese economy and the devaluation of the yuan, with its subsequent spillover effects, in particular for commodity exporters. The Spanish economy’s recovery gained traction in the second quarter of the year, although growth fell slightly short of FUNCAS’ forecast. Capital goods investments and industrial activity have been dynamic since the start of the recovery and their continued strength is the key to more –and more balanced and sustainable– future growth. The forecast scenario for the second half of the year and for 2016 remains basically unchanged, although the growth figure for 2015 has been cut by one tenth of a percentage point, and that for 2016 by two tenths, in the latter case partly as a result of the worsening global economic outlook.

International context

The outlook for the global economy worsened over the summer as a result of the slowdown in the Chinese economy. In the first two quarters of the year GDP grew by 7.0%, at the limit of the target set by the government for the year as a whole, although doubts exist as to the reliability of the figures. In the wake of the unexpected devaluation of the yuan in mid-August and the subsequent stock-market crash, the downward pressure on oil and other commodity prices intensified, with a deterioration in emerging economies’ growth expectations, particularly in the case of commodity exporters. These countries saw worsening capital outflows and a stronger depreciation of their currencies. Brazil stands out in particular, having now gone into recession.

Despite the strength of the U.S. economy, the worsening economic conditions in the emerging economies, which are likely to affect the growth of trade and the global economy, raised doubts about the Federal Reserve’s expected interest rate rise in September. The outlook for the U.S. has improved following the upward revision of GDP in the second quarter to 3.7% and the June and July employment figures. The unemployment rate has fallen to 5.1% and the real-estate sector is gaining momentum.

Growth in the euro area remains modest, although rates have been revised upwards to 2.1% (on an annualised quarter-on-quarter basis) in the first quarter and to 1.4% in the second. This sluggish growth is a result of weak domestic demand, particularly as regards investment. This weakness is reflected in the substantial current account surpluses in some countries, particularly Germany, which indicate considerable excess savings. This situation, combined with a context of a slowdown in the emerging economies, calls for an expansionary fiscal policy in the EMU, although it needs to be selective, based on each country’s situation.

The main risks to the stability of the global economy come firstly from the situation in China, which could worsen further as a result of the imbalances that have built up over recent years, such as the strong rise in debt and default, the property bubble, excess production capacity, and loss of competitiveness. Moreover, it is possible that if China ceases to play a leading role in demand for U.S. bonds, this could cause turbulence in international financial markets. A second potential source of instability may derive from the impact of the Federal Reserve’s rate rise on emerging economies, although it could also have an influence on long-term rates in the developed countries.

Recent developments in the Spanish economy

Spanish GDP grew by 1.0% in the first quarter of 2015 relative to the preceding quarter, equivalent to 4.0% on an annualised basis (the basis on which all the quarterly growth rates below will be expressed). This was slightly less than the 4.3% forecast by Funcas. Growth relative to the same quarter one year earlier was 3.1%. The contribution of domestic demand to annualised quarter-on-quarter growth was 4.7 percentage points (pp), while the external sector’s contribution was -0.7 pp.

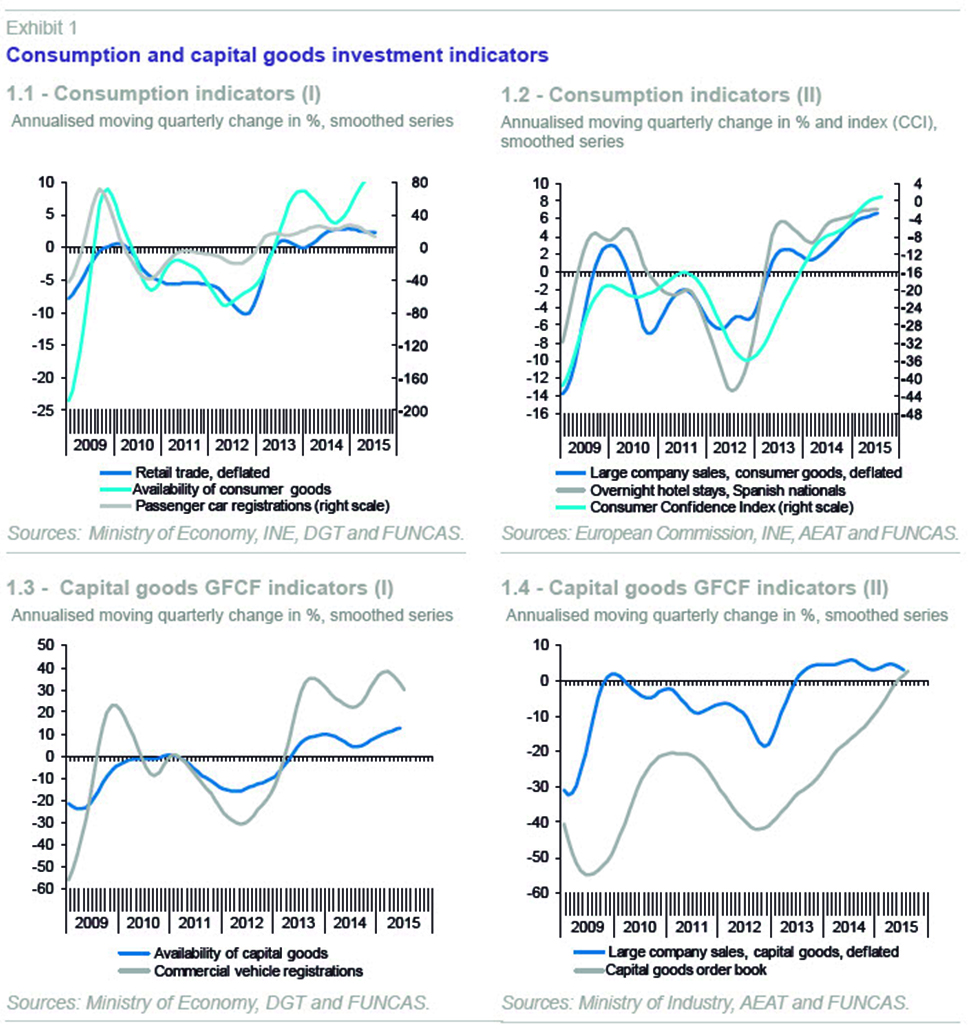

Growth in private consumption accelerated to 4%. Some of the indicators available for the start of the third quarter, such as retail sales or new vehicle registrations, show a slight downturn in their growth. Similarly, the July and August indices of consumer confidence and retail trade confidence are slightly lower relative to the previous quarter’s averages, although they remain at record highs (Exhibits 1.1 and 1.2). Nevertheless, the renewed drop in the oil price, and the bringing forward of the second part of the individual income tax reduction planned for next year make it seem likely that private consumption will gain strength again towards the end of the third quarter and in the fourth. Public consumption rose by 1.8%.

Investments in capital goods and other products remained strong in the second quarter, growing at a rate of 10.5%. At the start of the third quarter, registrations of goods vehicles and sales by large capital goods enterprises continued to slow (Exhibits 1.3 and 1.4). Construction investment continued to rise, driven by both residential construction, and above all, the other construction component, which is linked to the increase in public works in the run up to the local and regional elections. The recovery in the property market has continued to gain traction, and housing sales in the first seven months of the year grew by 10.5% compared to the year-earlier period, while prices, according to the INE, rose by 4% year-on-year in the second quarter.

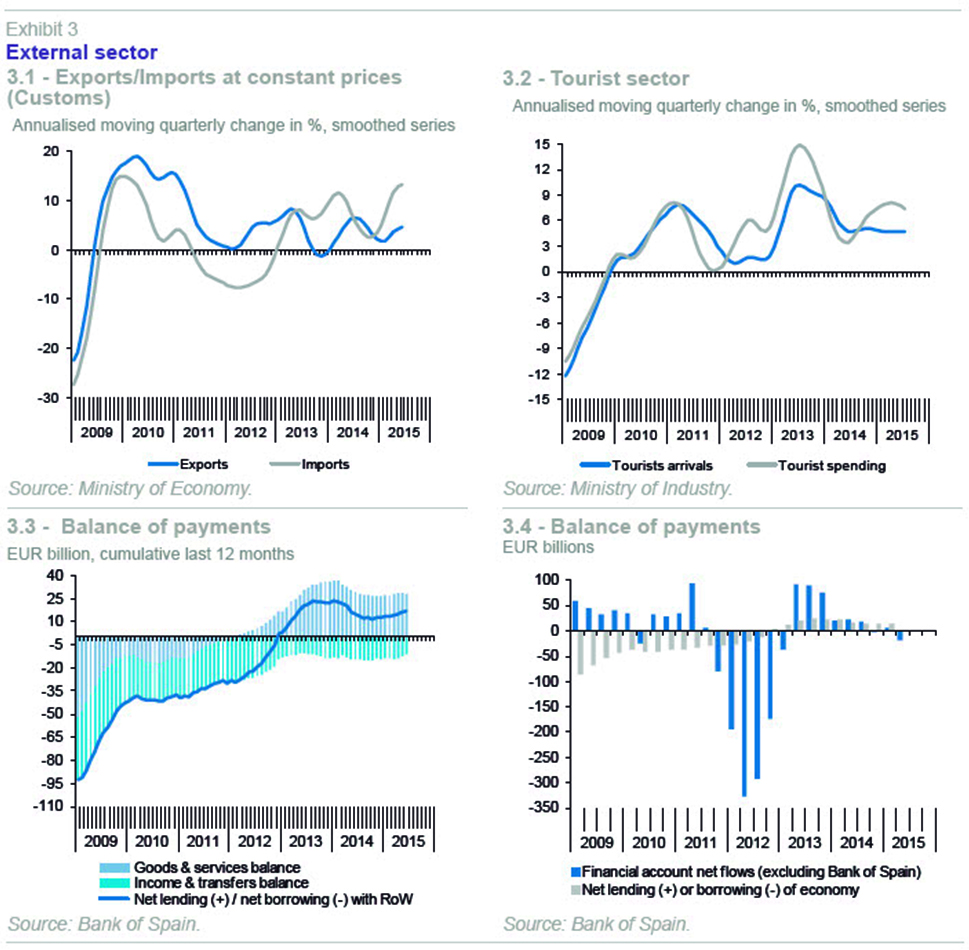

Total imports are growing faster than exports. Thus, the contribution of the external sector to quarter-on-quarter growth was negative, returning to the characteristic pattern seen since the start of the recovery, after two consecutive quarters in which its contribution was positive (Exhibit 3.1).

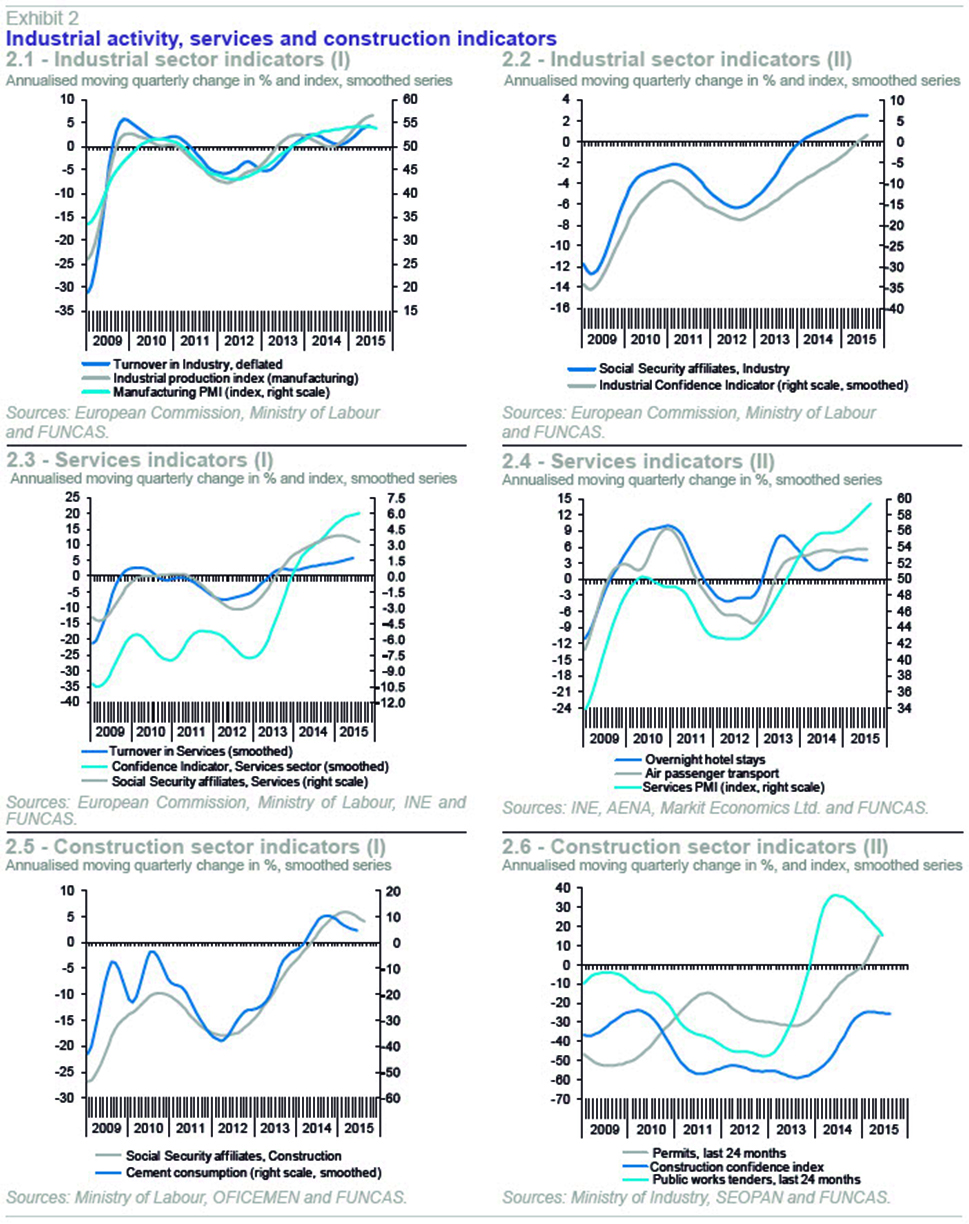

From the supply-side perspective, GVA grew in all sectors, with particularly strong growth in the manufacturing industry, which expanded by 6.6%. The information available for the third quarter indicates that the growth rate has remained healthy, although it has slowed somewhat. The result of the July industrial production index was favourable, although the July and August PMI and confidence index averaged slightly below the preceding quarter, and growth in Social Security affiliations in the sector also slacked off in both months (Exhibits 2.1 and 2.2). In any event, growth in both activity and employment in the sector showed its best performance since 2000. Thus, up until August, there had been 20 consecutive months of growth in the number of Social Security affiliates in the sector, which was unprecedented for this indicator since the historical series began in 2001.

In the case of services, the July and August PMI was above the previous quarter’s average, although growth in the number of Social Security affiliates slowed and the average of the confidence index is slightly below the previous quarter’s figure. Tourist arrivals in July continued to rise, although the downward trend in overnight stays by foreign tourists that began at the start of the year persisted. Overnight stays by Spanish residents increased, however (Exhibits 2.3, 2.4 and 3.2).

Recent trends for the number of Social Security affiliates in the construction industry suggests a sharp slowdown, probably as a result of public works linked to the electoral cycle coming to an end. This impression is confirmed by the drop in official tenders, which, after growing rapidly in 2013 and 2014, fell by 14.4% in the first half of the year. By contrast, new housing permits (building) continued to increase, and the trend is accelerating (Exhibits 2.5 and 2.6).

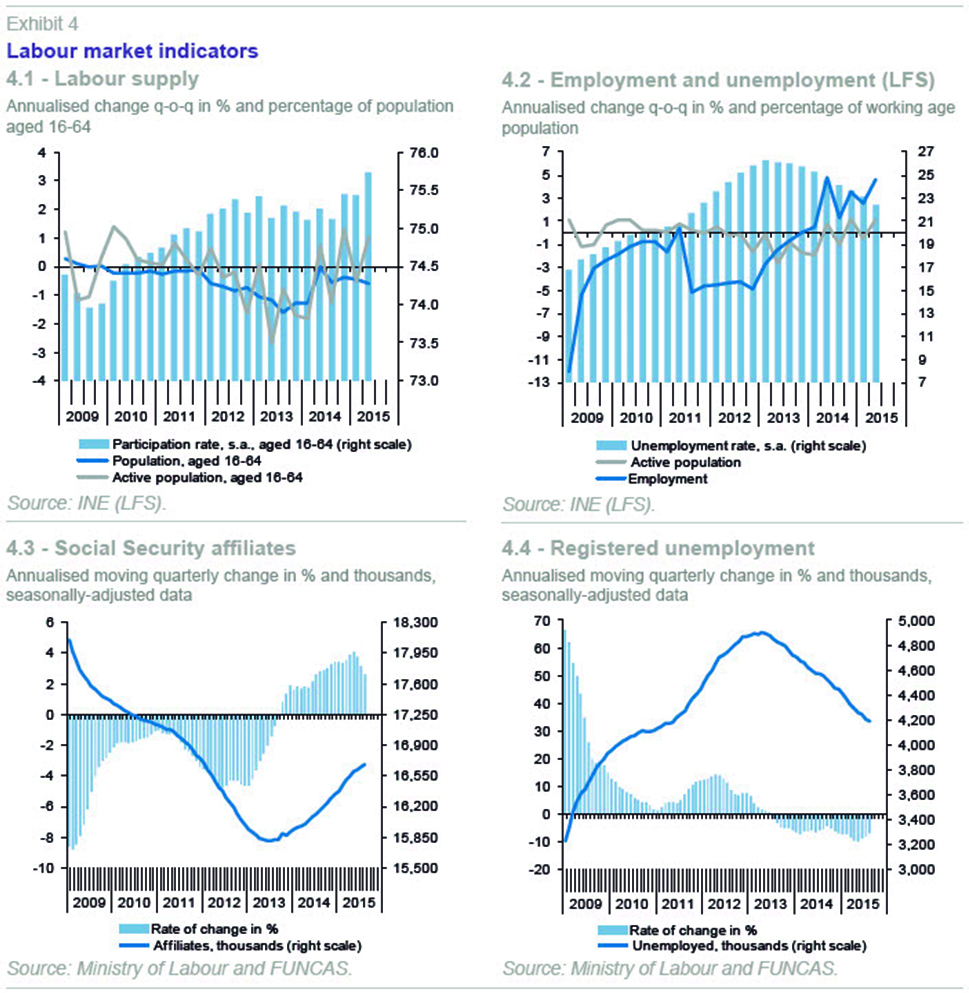

Employment, in full-time job equivalent terms, rose by 3.7% in the second quarter, with particularly strong growth in the manufacturing industry. Some of the most significant results of the LFS in the period were an increase in youth employment for the third consecutive quarter, and the fact that all the employment created has been full-time work, although the number of temporary workers has continued to rise faster than that of permanent ones. The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate fell by six tenths of a percent to 22.4% (Exhibits 4.1 and 4.2). The rate of job creation slowed in the third quarter, according to both the change in the number of social security system affiliates in July and August and the unemployment registered at public job centres (Exhibits 4.3 and 4.4).

Earnings per employee dropped by 2.3%, although this decrease was strongly influenced by the contraction in public sector wages. This contraction was the result of the comparison with the previous quarter, in which there was an increase due to the reinstatement of part of the extraordinary payment eliminated in December 2012. This effect caused unit labour costs to fall sharply in the second quarter. This variable fluctuates widely from one quarter to the next, but the trend suggests that the ongoing reduction over recent years has come to a halt, both in the manufacturing industry and the wider economy. However, its growth remains below that of the GDP deflator and the eurozone average.

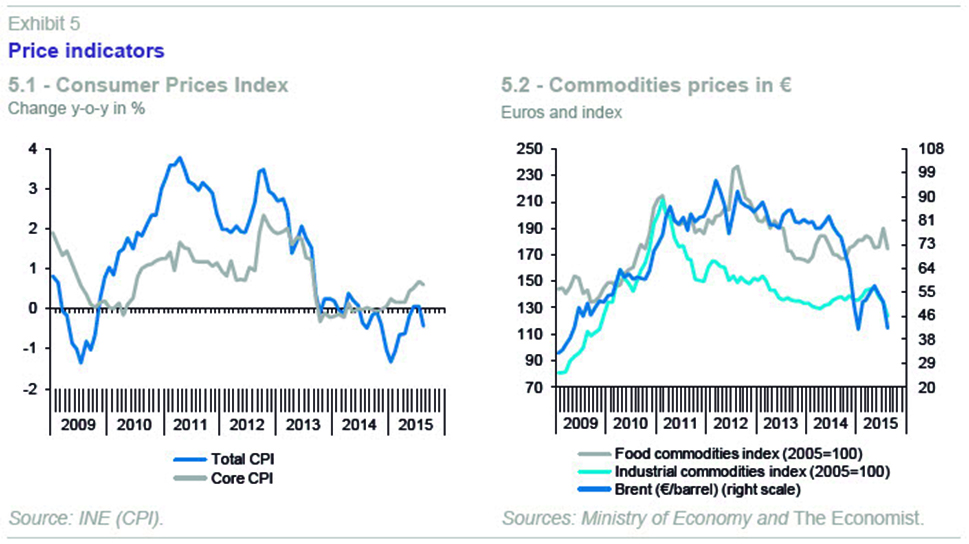

The inflation rate, which after eleven months in negative territory rose to 0.1% in June and July this year, dipped below zero again in August as a result of the falling oil price. The core inflation rate has been positive since December 2014, however, and has been on an upward path that reflects an increase, albeit still modest, in the upward pressure on prices driven by the recovery in consumption (Exhibits 5.1 and 5.2).

Although in real terms imports grew faster than exports in the first half of the year, the goods and services surplus was 10% higher than in the year-earlier period, as a result of the drop in the energy bill. This increase in the goods and services surplus was combined with a drop in the transfers and income balance deficit, giving rise to a slight current-account surplus, contrasting with the negative balance obtained in the same period of the previous year (Exhibit 3.3).

In the case of the financial account, there was a net outflow of 29 billion euros to June, more than twice the deficit recorded in the same period of the previous year, due to the drop in foreign investment flows into Spain, and in particular, the increase in Spanish investments abroad (Exhibit 3.4).

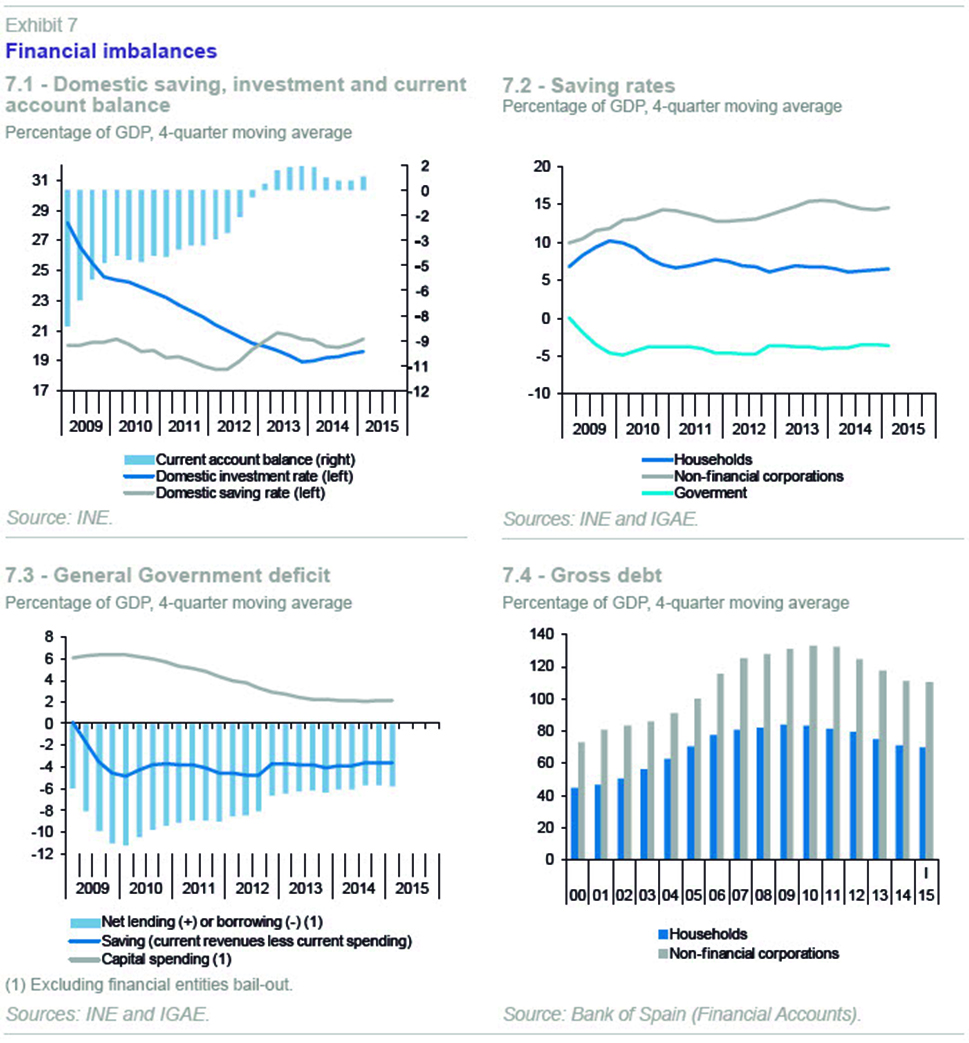

The national saving rate in the first quarter (calculated as the moving sum of four quarters) was 20.4% of GDP, three tenths of a percent more than in the previous quarter, as a result of a larger increase in disposable income than in nominal consumption. The investment rate also rose, although to a lesser extent than savings, giving rise to an increase in the economy’s net lending position of two percentage points, rising to 1.2% of GDP. By institutional sectors, this increase in the net lending position derived from an improvement in firms’ financial balances, while household and general government balances (excluding aid to financial institutions) barely changed (Exhibits 7.1 to 7.3).

Data to May shows the general government deficit (excluding local authorities) was 2.2% of GDP, just one tenth of a percentage point less than in the same period in 2014 (the target is to reduce it by 1.5 percentage points by the end of the year). In the case of the autonomous regions, the deficit up to May was 0.5%, one tenth of a percentage point less than in the year-earlier period, and only two tenths of a percent below its objective for the year as a whole.

Households’ debt dropped in the first quarter to 106.9% of their gross disposable income, the lowest ratio since 2005. Non-financial corporations’ debt dropped to 110.4% of GDP, which is also its lowest level since 2005. The general government, by contrast, increased its debt, according to the excessive deficit procedure, to 97.7% of GDP in the second quarter of the year, 1.7 percentage points above its level one year earlier (Exhibit 7.4). Spain’s external debt in the first quarter was 167.1% of GDP, compared with 157.9% in the year-earlier period. This increment was largely due to the increase in general government debt held by foreign investors.

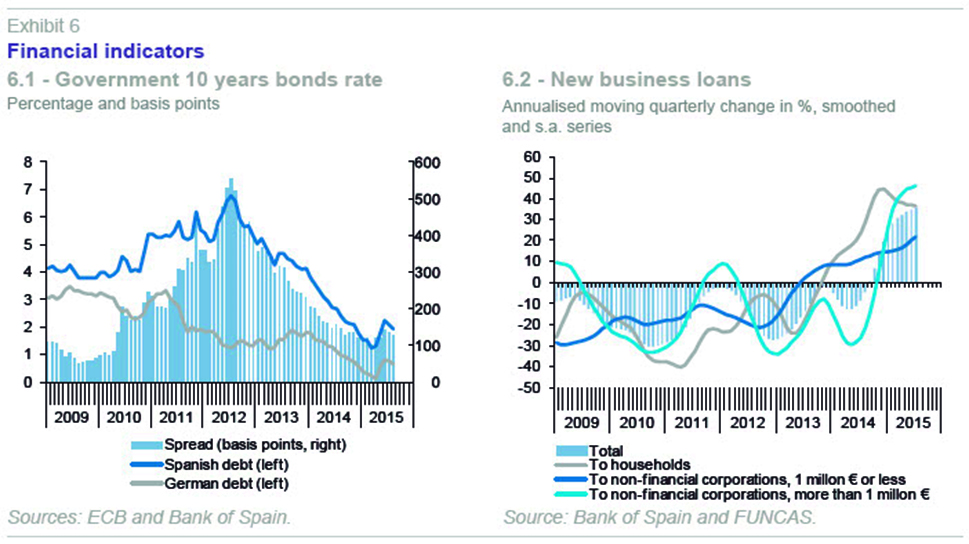

In June, the yield on ten-year public debt rose to almost 2.5% as a result of the tensions caused by the negotiations over the Greek bail-out, while the risk premium momentarily passed the 160 basis points level. The tensions subsequently subsided and debt yields returned to below 2%, but since August the turbulence associated with doubts about China has again pushed it above this level, while the risk premium has stood at around 140 basis points (Exhibit 6.1), exceeding Italy’s risk premium. This had not happened since early 2014 and is attributed to heightened domestic political uncertainties.

The stock of credit to firms and households continues to decline, as is to be expected given the process of deleveraging under way, although the rates are increasingly modest (2.8% in July). This is not incompatible with the increase in new credit, which in July presented a trend growth rate of 35% on an annualised quarter-on-quarter basis (Exhibit 6.2). However, it should be borne in mind that the volume of this new credit is still small compared with the volumes observed in the years before the crisis.

Forecasts for 2015-2016

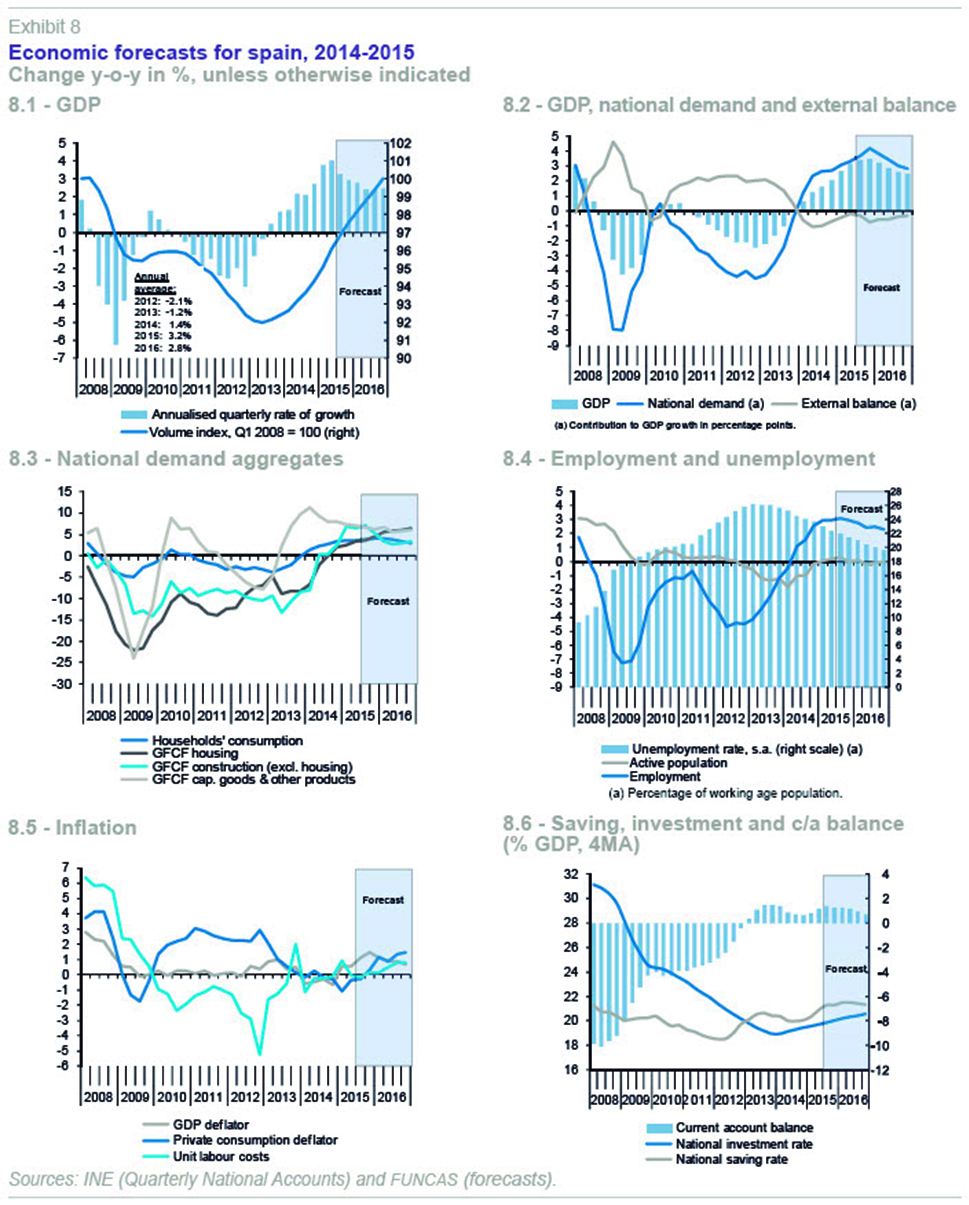

The impact of the worsening international context on the growth of the Spanish economy in the second half of 2015 will be limited, and offset by the beneficial effect of the drop in the price of oil and other commodities, together with the income tax cut being brought forward.In any event, the scenario of slower growth in the second half of the year envisaged in earlier forecasts–as a result of the transient effect of the positive shocks that have occurred in the first half wearing off–remains virtually unchanged in the forecasts (Exhibit 8.1). The changes in the economic indicators available for the third quarter, particularly social security affiliations, confirm this trend.

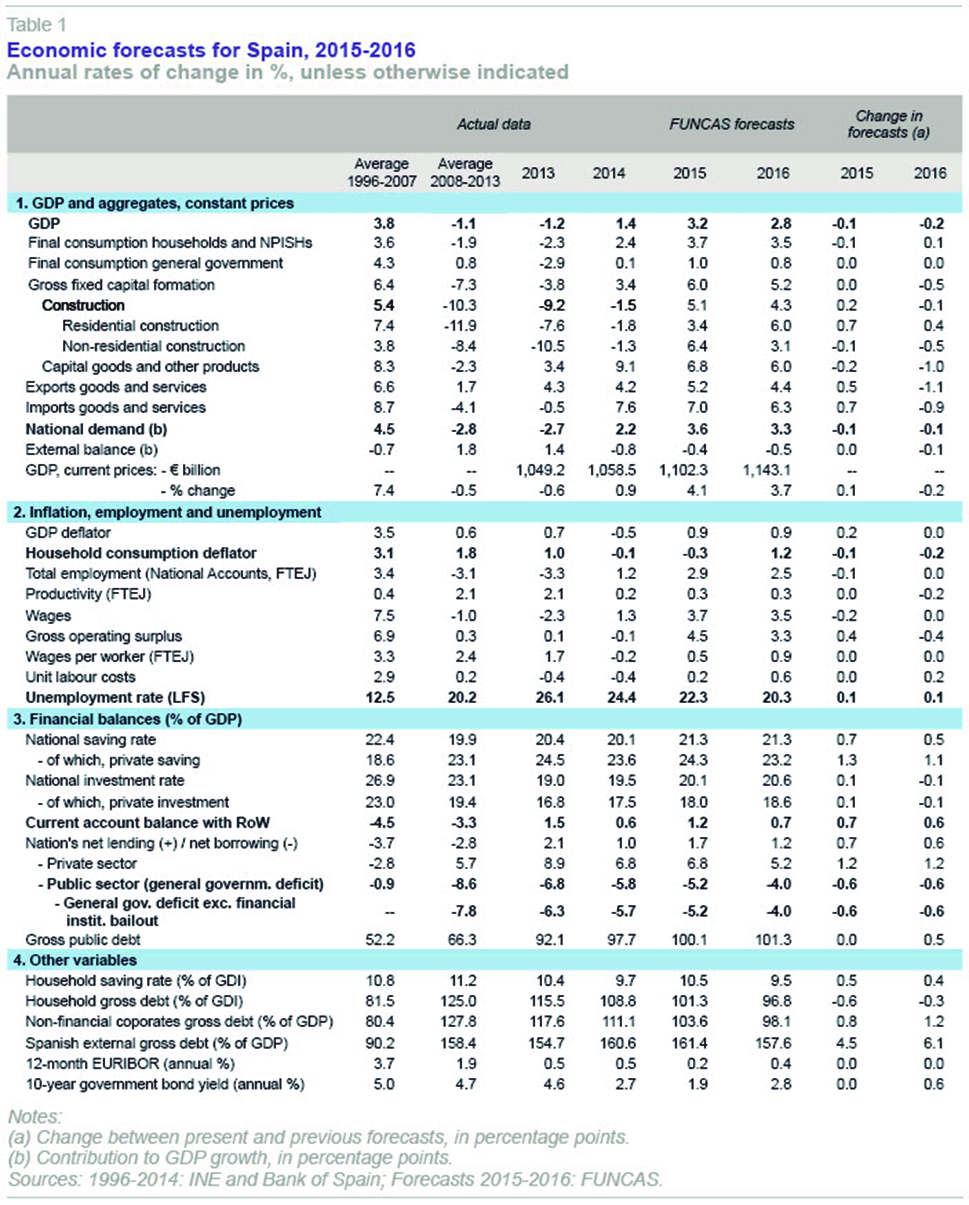

However, the fact that GDP growth in the second quarter has been somewhat less than expected makes it necessary to revise the forecasts for the year as a whole downward slightly. Thus, growth is expected to be 3.2% in 2015, one tenth of a percentage point less than in earlier forecasts. The forecasts for 2016 have been affected, firstly by the lower expected growth in the current year, and secondly by the global economy’s loss of dynamism. Unlike the case this year, this slowdown will not be offset by other effects, as the impact of the income tax cut and falling oil price will have worn off. The effect of these two factors on growth in 2016 will be modest, such that the forecast has been revised downwards by two tenths of a percent, to 2.8% (Table 1).

The main risks to this forecast scenario come from a more serious deterioration than expected in the external and financial context, or a possible intensification of domestic political uncertainties. These uncertainties could affect the spending plans of households and businesses, in particular, and could trigger a sharp rise in the risk premium, making external financing more expensive or more difficult to obtain.

Private consumption growth, that has been revised downwards by a tenth of a percent to 3.7% this year, will be driven by the upturn in household income and negative inflation. Growth next year will be more moderate, at 3.5%, as the increase in household incomes in real terms will be less than this year as the inflation rate is expected to turn positive (Exhibit 8.3). The forecasts for public consumption remain unchanged from the previous forecasts and are based on the assumption that growth this year will be greater than next as a consequence of the electoral cycle.

Growth of gross capital formation in capital goods has been revised downwards by two tenths this year and one percentage point next, as, along with exports, this variable will be hardest hit by the worsening international scenario and domestic political uncertainties.

Construction investment is expected to grow by 5.1% in 2015, which is slightly up on previous forecasts due to the upward revision of the figures for residential construction. In 2016 this component of demand will slow to 4.3%, despite the acceleration in the residential component, as the non-residential component will register more moderate growth than this year, during which its behaviour is influenced by the electoral cycle.

Exports should grow by 5.2% in 2015, but growth will slacken in 2016 for the reasons already mentioned. Imports will continue to grow faster than exports in both years, such that the net contribution of the external sector will be negative (Exhibit 8.2).

The forecasts for employment are barely changed. Employment is expected to increase by 2.9% in 2015 and 2.5% in 2016, in full-time equivalent job terms, implying 900,000 more jobs over the two years as a whole. The average annual unemployment rate will drop this year by 2.1 percentage points to 22.3%, and a further two percentage points next year (Exhibit 8.4). Unit labour costs will rise in both years for the first time since 2009, although the increase will be less than is forecast for the euro area.

The Spanish economy’s rate of inflation, measured using the GDP deflator, will remain at moderate levels (below 1% in both years), although lower import prices, caused by less expensive oil, will mean consumer price inflation will be negative in 2015 (Exhibit 8.5).

The current account surplus will double this year, reaching 1.2% of GDP, despite the external sector’s negative contribution to growth, as a result of the drop in the oil price (Exhibit 8.6). This forecast scenario assumes that crude oil will cost an average of 54.3 dollars (48.8 euros) a barrel in 2015 and 56 dollars (51.7 euros) in 2016.

Finally, the general government deficit has been revised upwards to 5.2% of GDP this year and 4% of GDP next, overshooting the official targets in both cases (4.2% and 2.8%, respectively).

To conclude, the economic recovery in the second quarter has continued to show signs of considerable strength. On the demand side, these include the dynamism of capital investment, and on the supply side, the vibrancy of the manufacturing industry. The outlook for the second half of this year and for next year remains favourable, despite the slowdown expected. The slight downward revision of the forecasts does not respond to a substantial change in scenario, but is simply a technical adjustment with respect to 2015. In the case of 2016 it is also the result of the incorporation of the somewhat less favourable outlook for the external sector, although the impact is expected to be limited.

Nevertheless, it is important that the two features of the Spanish economy’s behaviour mentioned –the dynamism of investment and manufacturing–, which are the result of cost competitiveness gains, are consolidated and sustained over time, as they are the route enabling a transition towards a more balanced and sustainable model of development for the future, and towards the economy’s enhanced long-term growth capacity, which is to say, a higher potential growth rate.

Ángel Laborda and María Jesús Fernández. Economic Trends and Statistics Department, FUNCAS