Key features of the 2016 General State Budget

The goals of the 2016 budget are to stimulate growth and continue on the path of fiscal consolidation. Improving macroeconomic conditions support the government´s optimistic revenue forecasts in the face of tax cuts, while cost savings will come largely through reductions in unemployment benefits and debt service payments.

Abstract: The government has recently presented its draft 2016 General State Budget for parliamentary debate, ahead of schedule. The main objective of this year´s proposal is fiscal consolidation. According to the government´s forecasts, the general government deficit is projected at 2.8% of GDP – converging close to budgetary equilibrium in 2018. Although optimistic, revenue forecasts take into account the expected improvement in economic conditions, together with the anticipated effects of the 2015 tax reform applied to income and corporate taxation. On the expenditure side, the government anticipated an overall cut of 3.0% versus 2015, supported by decreases in unemployment benefits, economic activities, and a reduction in debt servicing costs.

Fiscal consolidation and growth

On July 31st, the Council of Ministers passed the 2016 draft General State Budget. The approval came somewhat ahead of the usual schedule to ensure the budget is duly debated and passed before the end of the current legislative period, given that general elections must be held no later than December 20th, 2015. Final approval of the budget is scheduled for the week of October 19th-23rd, at least two months earlier than usual. Given that the People’s Party is currently governing with an absolute majority, few amendments are expected to the draft to be debated in the two legislative houses.

The execution of the budget under the terms in which it is passed will, however, depend on the results of the forthcoming general elections. The results of surveys of voting intentions have so far suggested a climate of political uncertainty, in terms of the sign and composition of the next national government. This poses a not insignificant risk for the growth forecast scenario, recently revised down by FUNCAS, which has cut its forecast by one and two tenths of a percent for 2015 and 2016, respectively, to 3.2% in 2015 and 2.8% in 2016.

Against this background, this article aims to give an overview of the main features of the 2016 State Budget.

[1] The draft contains the details of estimated revenue and expenditure of the State, Social Security Fund, and the autonomous and state agencies.

[2] The goals of the 2016 budget, drafted under the auspices of the 2015-2018 Stability Programme update and the National Reform Plan,

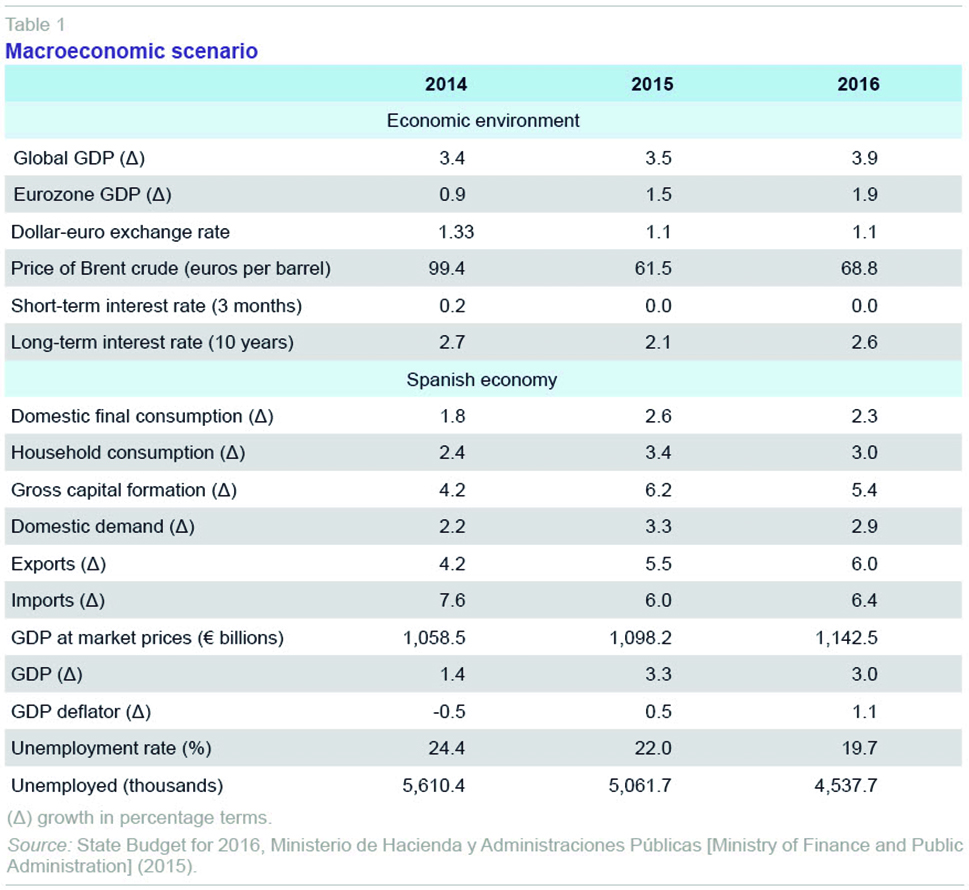

[3] are to stimulate growth and continue on the path of fiscal consolidation. The macroeconomic scenario used to prepare the budget presented in Table 1 assumes moderate growth of both the global economy and the euro area, although tending towards acceleration.

[4] In the case of the euro area –Spain’s main trading partner, taking 65% of its exports– growth is expected to rise from 1.5% in 2015 to 1.9% in 2016 as a result of the European Central Bank’s expanded public and private debt purchase programme (quantitative easing), the depreciation of the euro and the progress of the oil price. A dollar-euro exchange rate of 1.10 is expected, alongside an average oil price of 68.8 euros a barrel (compared with 61.5 euros in 2015). In this context, the 2016 GDP growth forecast is for 3% compared with 3.3% in 2015 and 1.4% in 2014, confirming the Spanish economy’s recovery.

[5] A key factor in this growth will be the behaviour of domestic demand, for which a growth of 3% in household consumption and 5.4% in investment is estimated–after seven years of adjustment, investment in housing is set to grow by 3.2% in 2015 and 5.2% in 2016. Economic growth will make it possible to continue bringing down the unemployment rate, which for the first time since the crisis will drop to below 20% (19.7%).

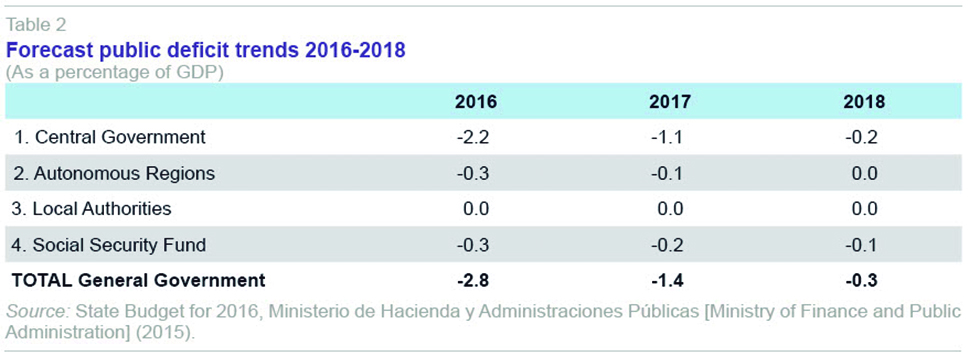

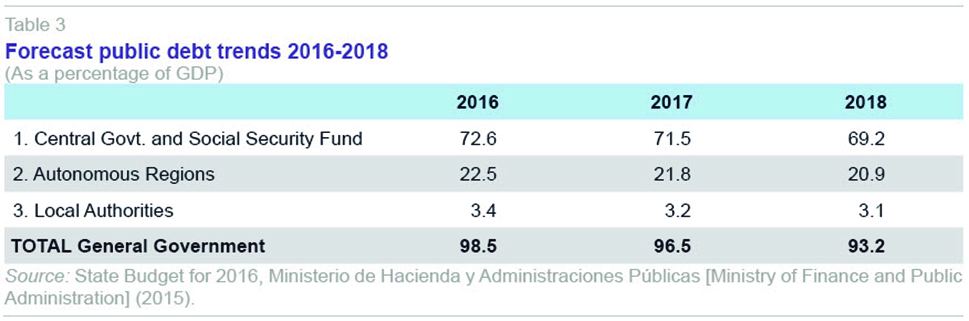

Table 2 shows the deficit forecasts for the total general government over the period 2016 to 2018. This reflects the fact that the process of fiscal consolidation will make it possible to come close to budgetary equilibrium in 2018 (with a deficit of 0.3% of GDP). For 2016, the maximum deficit is set at 2.8% of GDP, which implies a drop of 1.4 points with respect to the previous year –a long way, therefore from the -11.0% reached in 2009 at the height of the economic crisis. The limit set for 2016 coincides with the excessive deficit recommendations drawn up by the European Union in June 2013. The growth threshold for the central government deficit will be 2.2%, reaching 0.3% in both the autonomous regions and social security –local authorities will remain in budgetary equilibrium. One key feature of the 2016 budget is the existence of a primary surplus (of 0.35% of GDP) for the first time since the start of the crisis. As Table 3 shows, the debt level set for the general government as a whole is 98.5% of GDP in 2016. The debt of the central government and the Social Security Fund comes to 72.6% of GDP, that of the autonomous regions 22.5%, and the remainder corresponds to local authorities. The government expects the level of debt to fall by two points in 2017 and 5.3 points in 2018, with the appearance of a primary surplus across the general government as a whole. Alongside the debt and deficit figures, the 2015-2018 Stability Programme offers estimates of public expenditure and fiscal pressure. Here, the government is confident that fiscal pressure will remain at 38% of GDP, despite the impact of the reform to personal income tax (IRPF in its Spanish initials) and corporate tax (IS), which will be discussed in more detail below. Indeed, growth in revenues from indirect taxes and the tax base for personal income tax are expected to offset the effect of the reform. Similarly, the weight of public expenditure in GDP will be reduced by five points, from 43.5% in 2014 to 38.4% in 2018, on the hypothesis that public expenditure will grow less than GDP.

Revenue forecasts

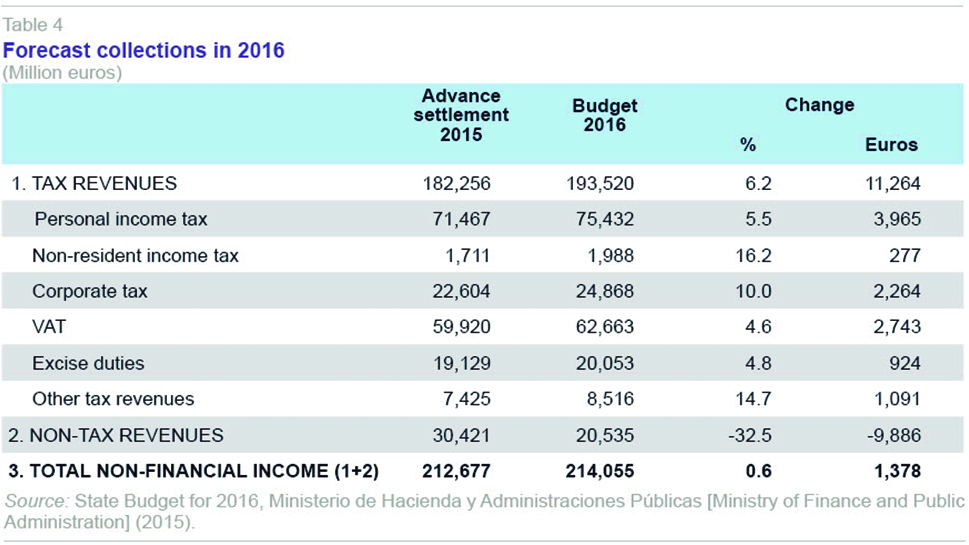

The revenue forecasts assume nominal GDP growth of 4% and an increase of close to 1% in the tax base. In this macroeconomic scenario, the State’s non-financial revenue in 2016 is expected to come to 214.06 billion euros, which is 3.91% more than the initial budget for 2015. Tax revenues are expected to total 193.52 billion euros, representing 90.4% of non-financial revenue, which is a similar figure to that for 2015. As regards the 2015 advance settlement, the latest data available (Table 4) show that tax revenues will grow by 6.2% in 2016 (direct taxes by 6.8% and indirect taxes by 5.6%). However, it should be noted that the 2015 advance settlement forecasts slightly lower revenues than those initially budgeted for. To be precise, the deviation will be 1.49 billion euros from IRPF, 340 million euros from VAT, 973 million euros from corporate tax, and 765 million euros from excise duties, making a total deviation of 3.57 billion euros. For its part, the government estimates that non-tax revenue will fall by 32.5% in 2016, with a particularly sharp drop in public fee revenues (-56.8%).

Broken down by tax types, revenue from income tax will grow by 5.5%, that from VAT by 4.6%, corporate tax 10%, and excise duties 4.8%. The government bases its estimated strong growth in personal income tax revenues on the positive trend in wage income, where growth of 3% in paid employment and 1.4% in wage income is expected. The forecast for VAT is based on an acceleration in prices and an improvement in the residential property market. The government explains its strong forecast growth in corporate tax revenue through the favourable progress of company profits and the broadening of the tax base. Lastly, the increase in excise duties is basically explained by strong growth in the consumption of fuels and natural gas. The growth forecasts for tax revenues in 2016 look somewhat optimistic when compared with the 3% growth in GDP expected. Indeed, as we have discussed elsewhere (Sanz and Romero, 2014), this increase in revenues is only possible with a very high elasticity of revenue collection relative to the economic cycle, something that has not been shown by available empirical evidence.

The 2015 tax reform affecting income tax and corporate tax was taken into account in the revenue forecasts (the structures of VAT and excise duties are unchanged in 2015 and 2016). As regards the timing of these reforms, the government’s plans were to implement the reform of these two taxes in two phases (for more details, see Sanz and Romero, 2014). The first of these two phases was due to come into effect on January 1

st, 2015, as was the case (Law 26/2014). The second phase was due to come into force on January 1

st, 2016, after the end of the current legislative period. However, the government decided to bring forward the second phase of the income tax reform to July 2015, on the basis of arguments such as the good progress of the economy, backed as we have seen by the IMF and OECD, and tax revenues, which rose by 7.4% in the period up to May. The second phase of the income tax reform was almost exclusively focused on cutting the tax rates in both the general and savings tax bases (Sanz and Romero, 2014).

[6] Consequently, there are now four income tax scales in 2015, two general and two for savings, which will apply depending on the date on which taxpayers obtained their earnings. However, to make things simpler, the government has revoked the two scales existing before the reform, to create a new general scale and savings scale applicable to income earned over the whole year. The marginal rates for these two new scales are half way between those in force up until July 2015 and those due to be implemented in 2016 (Sanz and Romero, 2014). For the purposes of illustration, Table 5 shows the rates in effect in 2014 and those that will apply in both 2015 and 2016. As can be seen, the number of brackets in the general scale has been cut from seven to five, while the lowest and highest marginal rates have been reduced (from 24.75% to 19.5%, and from 52% to 46%, respectively). For its part, the savings scale has kept the same number of brackets, but the marginal rates in all of them have been lowered. For instance, for small savers, with earnings of less than 6,000 euros, the rate has been cut from 21% to 19.5%.

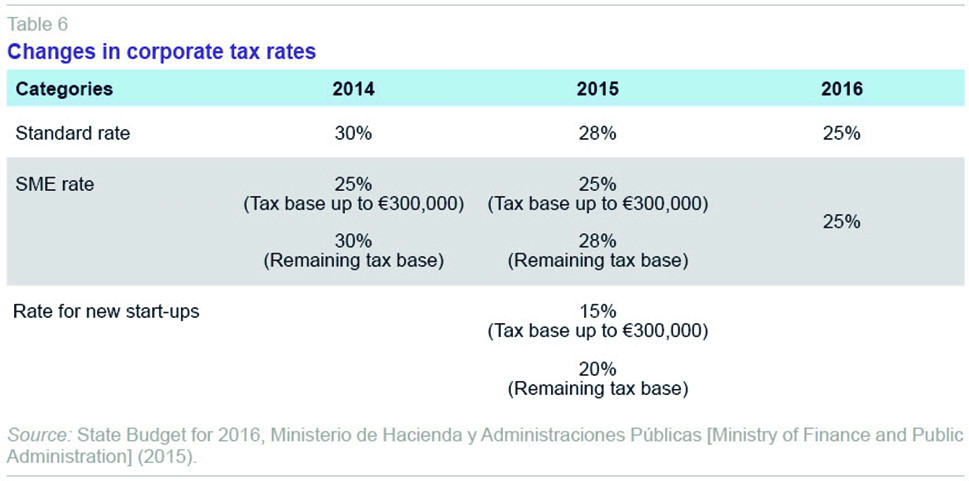

The second phase of the corporate tax reform will be implemented in 2016, continuing the cut in rates begun in 2015. As of 2016, the tax rate applicable, both generally and to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs),

[7] will be 25%.

[8] As can be seen in Table 6, after the two phases of the reform, the general tax rate will have dropped by 5 points, thus coming closer to the rates in effect in neighbouring countries, the EU-28 average being 22.9% in 2004 (Eurostat, 2014).

[9] This rate cut was bigger than that in other European countries such as Finland (from 24.5% to 20%), the United Kingdom (from 23% to 21%), Slovakia (from 23% to 22%) and Denmark (from 25% to 24.5%). Moreover, equalising the rate for SMEs with that applicable to other firms may help increase firms’ size by softening the negative tax impact of their scale. This is important in a country like Spain, where 92.4% of firms have fewer than 10 employees (micro-enterprises), 6.4% have between 10 and 50 employees (small) and just 1% have between 50 and 250 employees (medium sized) (Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism, 2015).

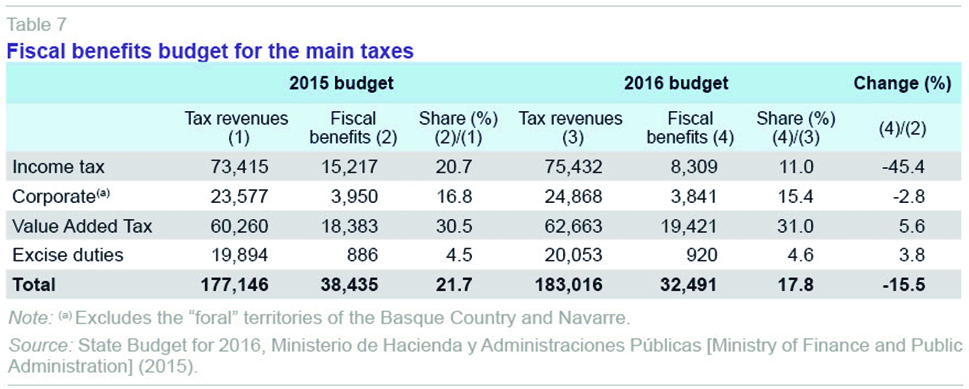

Following the constitutional mandate, the General State Budget includes the Budget for Fiscal Benefits (PBF in its Spanish initials), the aim of which is to offer estimates of the loss of revenue caused by the existence of exemptions, reductions, reduced rates, etc. For illustration, Table 7 compares the fiscal benefits in 2015 and 2016 in the four main taxes (income tax, corporate tax, VAT and excise duties). In 2016, the reduction in revenue resulting from fiscal benefits totalled 32.49 billion euros, close to a fifth (17.8%) of the expected revenue. Nevertheless, the government estimates that the fiscal benefits will drop by 15.5% in 2016, equivalent to 5.944 billion euros. This reduction is basically explained by the changes in the structure of income tax, which came into effect on January 1

st, 2015, but will have an impact on the 2016 settlement (note that the PBF is prepared on a cash rather than accruals basis). Specifically, the fiscal benefits applicable to income tax will be reduced by 6.91 billion euros, basically as a result of the change in the design of the reduction for employment income, which will reduce the fiscal benefits by 6.18 billion euros. By contrast, the fiscal benefits applicable to VAT will increase by 1.04 billion euros, reaching 31% of the expected revenue in 2016 (19.42 billion euros). The fiscal benefits applicable to VAT are the result of various exemptions (8.07 billion euros), the existence of a reduced rate of 10% (7.92 billion euros) and the super-reduced rate of 4% (3.25 billion euros). The fiscal benefits applicable to the corporate tax come to 3.84 billion euros, as a consequence of the various deduction, provisions, accelerated depreciation, or reduced rates for SMEs.

Estimated expenditure

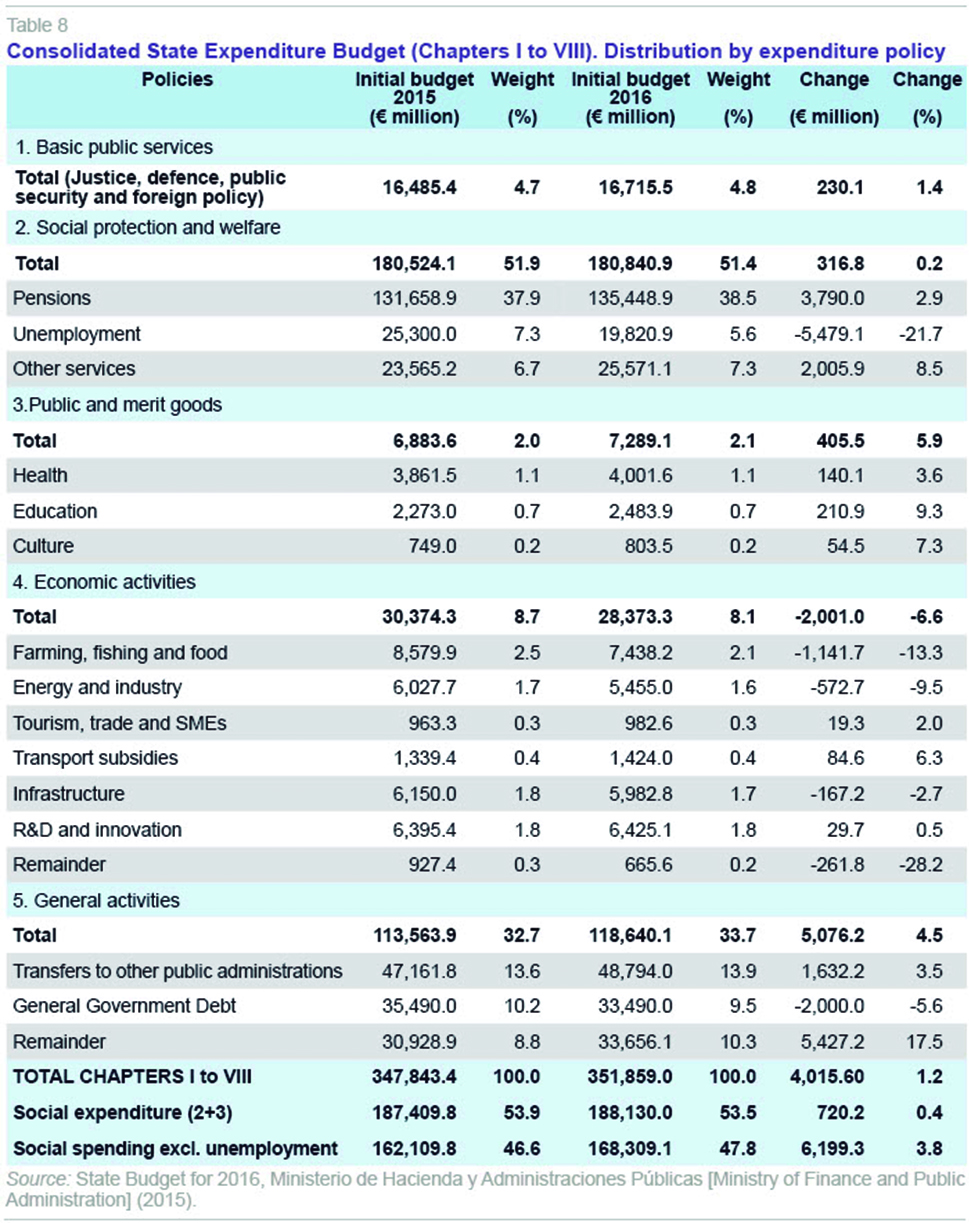

Table 8 summarises the consolidated expenditure of the central government, the Social Security Fund, and autonomous and state agencies. Its figures give an overview of the objectives and priorities pursued by the government both as a whole and through its five main expenditure blocks: (i) basic services; (ii) social protection; (iii) merit goods; (iv) economic activities; and (v) general activities. Consolidated State expenditure will be 351.86 billion euros in 2016 (Chapters I to VIII), with growth of 1.2%, equivalent to 4.015 billion euros (0.35% of GDP in 2016).

[10] The central government will manage 46.7% of consolidated spending, the social security system 40.0%, autonomous agencies 11.4%, and the remaining 1.9% will be managed by state agencies, and other public sector bodies.

The basic services offered by the State–justice, defence, public security, and foreign policy–will grow by 1.4% in 2016 (230.1 million euros). 41% of this increase will be devoted to implementing e-government in the justice system, with the aim of gradually eliminating the use of paper. This modernisation programme will cost about 95 million euros.

Social spending includes social protection and promotion policies, essentially pensions and unemployment benefits, and spending on merit goods, such as health, education and housing. Note that the spending on merit goods is much less than that on social protection and promotion, as competences for these services have been transferred to the autonomous regions. Social spending will increase by 720 million euros, with an increase of 0.4%. The behaviour of the items accounting for the largest share of social spending, namely pensions and unemployment benefits, will diverge in 2016. Specifically, pensions, which account for 71.9% of social spending, will increase by 3.79 billion euros. For their part, unemployment benefits, which account for 10.5%, will drop by 5.48 billion euros.

Table 8 shows pension payments, including both contributory pensions and non-contributory pensions, civil service pensions, and survivors’ and orphans’ pensions. Overall, pensions will absorb 38.5% of the State’s consolidated expenditure in 2016, totalling 135.45 billion euros, with growth of 2.9%. This change is a consequence of the increase in the number of pensioners, the increase in average pensions (new pensions are on average 37% higher than those of pensioners who die) and a pension increase of 0.25%. Total pension expenditure comprises 118.941 billion euros in Social Security contributory pensions (87.8% of the total), 13.46 billion euros in civil service pensions (9.9%), and the rest in the form of non-contributory pensions.

Unemployment benefit payments will come to 19.82 billion euros in 2016, 60% in the form of contributory benefits, and with an estimated 751,440 beneficiaries. The remaining 40% will be devoted to non-contributory benefits, including farm income support. Overall, the estimated expenditure on unemployment protection is expected to drop by 5.48 billion euros in 2016 thanks to the improvement in the job market.

[11] Thus, the Labour Force Survey data for the second quarter of 2015 recorded 437,000 fewer unemployed persons and 513,500 more employed persons than in 2014 as a whole. For this reason it is expected that the unemployment rate will drop to 19.7% in 2016, this being the first time since the fourth quarter of 2010 in which it has dropped below 20% (the unemployment rate peaked at 26.94% in the first quarter of 2013).

The economic activities include a wide variety of policies in productive sectors of the economy such as agriculture, industry, tourism, energy, transport, infrastructure and R&D. These expenditures came to 28.37 billion euros in 2016, a drop of 6.6% (2.0 billion euros). The budgetary allocation will decrease in agriculture and fisheries (1.141 billion euros), industry and energy (572 million euros) and infrastructure (167 million euros). The reduction in agriculture spending (13.3%) is the result of the termination of the EAGF and ERDF (88% of these policies is financed with European funds). Public investment in infrastructure, a basic instrument for stimulating growth and productivity, will drop by 2.7% relative to 2015. This figure will be virtually unchanged, however, if the investments of state-owned companies are taken into account. Conversely, the budgetary allocation to trade, tourism and SMEs (19.3 million euros), transport subsidies (84.6 million euros), and investment in research, development and innovation (29.7 million euros) will rise. In the case of civilian R&D and innovation, the budgetary allocation will be increased by 125 million euros, while its military counterpart will be cut by 95.8 million euros. This group includes, in particular, the 3.9 billion euros devoted to financing the costs of the electricity system (part of which is financed from a tax on electricity generation created in 2012 and another part from an auction of greenhouse gas emission rights).

Finally, expenditure on general activities will grow by 4.5% to 118.64 billion euros in 2016. This group includes transfers to the autonomous regions and local government bodies (48.79 billion euros) and the financial expenses on the public debt (33.49 billion euros), State staff and consulting costs (633 million in 2016), general services, comprising a total of 25 different programmes

[12] (34.07 billion euros) and tax and financial administration costs

[13] (1.66 billion euros). One issue to highlight in this group is the 2 billion euro reduction in the cost of interest on public debt, a drop of 5.6%. This drop is basically explained by the reduction in the debt level. For the central government and the social security system, the level of debt will drop from 76.3% of GDP to 72.6% in 2016. For the general government as a whole, the drop will be from 101.7% to 98.5%. The government expects that the joint debt of the central government and social security system will continue to fall over the coming years, dropping to 69.2% of GDP in 2018 (93.2% for general government as a whole).

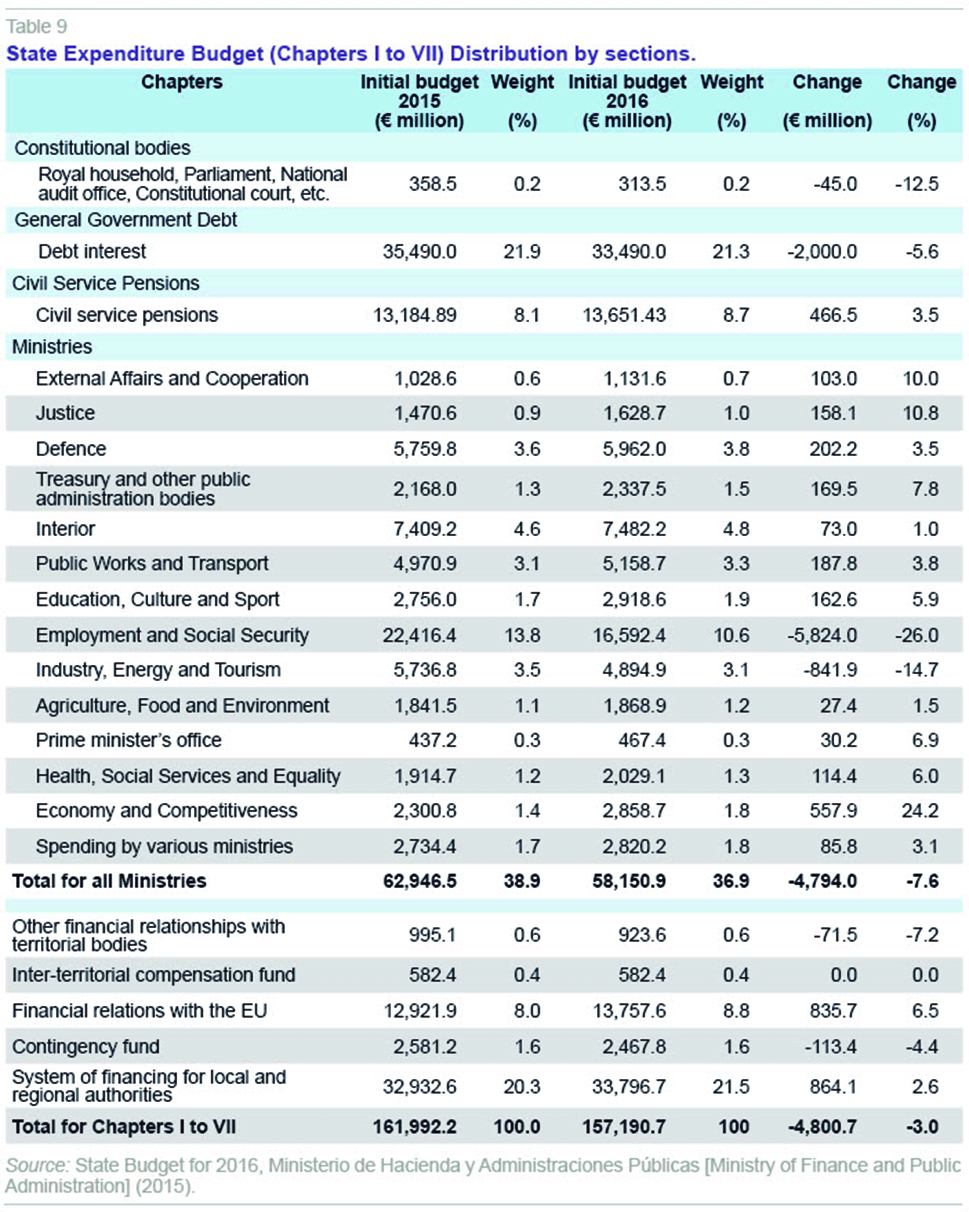

State budget

As can be seen in Table 9 (Chapters I to VII), 36.9% of State spending will go to the ministerial departments, 21.5% to transfers to the autonomous regions and local authorities, 21.3% to interest on the debt, and 8.7% to civil servants’ pensions. As a result of the process of fiscal consolidation, the budget for the ministerial departments has been cut from 79.208 billion euros in 2011 to 58.15 billion euros in 2016, a reduction of almost 21.058 billion euros (a drop of 26.5%). The financial expenses in the budget have risen from 27.40 billion euros in 2012 to an expected 33.49 billion euros in 2016, with an increase of 6.070 billion euros (an increase of 22.13%). The ministry managing the largest volume of resources in 2016 will be Employment and Social Security (10.6%), as it is responsible for paying unemployment benefits through the State Employment Service. It is followed by the ministries of the Interior (4.8%), Defence (3.8%) and Public Works (3.3%). Spending by most ministries will rise in 2016, with Economy (24.2%), Justice (10.8%) and Foreign Affairs (10%) being those receiving the biggest increases. Spending will drop in 2016 in the ministries of Employment and Social Security (26%), and Industry, Energy and Tourism (14.7%).

Social Security budget

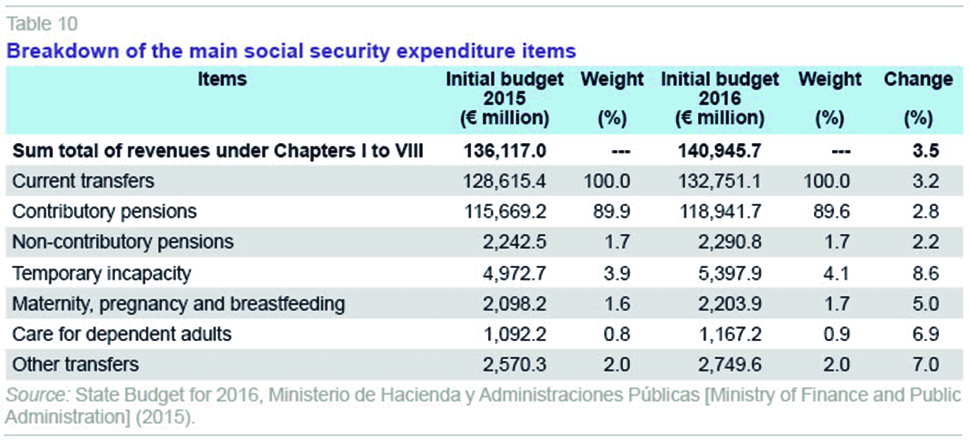

Social security spending will come to 140.95 billion euros in 2016, an increase of 3.5% (Table 10). As mentioned above, this change is due to the rising numbers of pensioners, new pensioners’ larger average pension, and the 0.25% rise in existing pensions. 94.1% of Social Security spending corresponds to current transfers to households, including contributory and non-contributory pensions, temporary disability, pregnancy and maternity, family protection, cessation of activity of self-employed persons, and other economic benefits. Contributory pensions make up the bulk of current transfers, with estimated expenditure of 118.94 billion euros in 2016, an annual increment of 2.8%. The biggest contributory pensions item is retirement pensions (83.56 billion euros), followed at some distance by survivors’ pensions (21.04 billion euros), disability (12.23 billion euros) and orphans’ pensions (2.10 billion euros).

The Social Security Fund’s main source of financing is employees’ and employers’ contributions, which represent 83.2% of total revenues. The biggest share of contributions are those of Social Security contributors in the general system. Employers contribute an amount equivalent to 23.6% of employees’ gross salary, while employees’ contributions represent 4.7% of their salary. Revenue from contributions in 2016 is expected to come to 117.24 billion euros, with an increase of 6.7% with respect to the preceding year. The government justifies this sharp rise with the interaction of four factors. Firstly, the rising number of social security system affiliates observed since 2014, in both the general system and the special system for self-employed persons: it is estimated that improvement in the employment situation will boost social security contributions by 8.3%. Second, the favourable evolution of the economic growth forecasts (4% nominal growth) and employment levels (3%) and the maximum contribution limit (1%). Third, the expected increase in average wages (1.4%). And finally, improvements in combating fraud. It should also be noted that the Social Security Fund is topped up with contributions from the State. These contributions will come to 13.16 billion euros in 2016, an increase of 0.7%. This sum is mainly used to cover minimum pension complements, which will come to 7.41 billion euros in 2016.

Budget for autonomous and state agencies

The State Budget includes a total of 59 Autonomous Agencies (operating in a wide range of spheres of public activity) and 9 State Agencies (differentiated by their degree of autonomy and management flexibility). In terms of the volumes of resources they manage, the largest Autonomous Agencies are the Public State Employment Service (responsible for paying unemployment benefits) with a budget of 25.18 billion euros, the Agricultural Guarantee Fund (6.91 billion euros) and the State Civil Service Pensioners’ Mutual Fund (1.67 billion euros). The largest of the State Agencies by volume of resources is the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), with a budget of 630 million euros, the Spanish International Development Cooperation Agency (AECID) with a budget of 252 million euros, and the National Meteorology Office (AEMET) with a budget of 122 million euros. Overall, the budget allocated to Autonomous and State Agencies will come to 41.84 billion euros in 2016, a reduction of 13.04%. 80.7% of this reduction is basically explained by the decrease in unemployment benefits.

Notes

See the “yellow book” of the draft State Budget 2016 for more details.

The 17 autonomous regions, 2 autonomous cities, and more than 8,000 municipalities in Spain are not included in the General State Budget, except as regards the transfers they receive.

Both sent to the European Commission as part of Member States’ obligations.

The scenario in which the budget has been prepared has been endorsed by the Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority (AIReF).

These growth rates are in line with those published by the IMF, OECD and FUNCAS. Thus, last July the IMF raised its growth forecasts to 3.1% in 2015 and 2.5% in 2016. These estimates put Spain in the lead among developed countries. The review of the forecasts by the OECD in June 2015 put GDP growth at 2.9% in 2015 and 2.8% in 2016. The September FUNCAS panel forecast estimated GDP growth at 3.2% in 2015 and 2.8% in 2016.

In this context all the withholdings have been adjusted. In the case of the self-employed, the withholding has gone from 19% to 15%. According to the government, this modification will make it possible to boost self-employed persons’ liquidity by an average of 263 euros.

In Spain, SMEs are firms with fewer than 250 employees and a turnover of less than 50 million euros.

Newly created firms are an exception to this rule as they will be liable for a rate of just 15% on the first 300,000 euros of their tax base.

It should be recalled that in 2014 Spain was among the EU-15 countries with the highest statutory tax rates, along with Belgium, France, Germany and Italy.

The limit on non-financial State expenditure for 2016 is 123,394 million euros, with a drop of 4.4% relative to the previous year’s budget. This reduction is due to the smaller financial burden of interest on debt, and the reduction in expenditure on unemployment benefits.

However, it should be borne in mind that there has been a transfer of beneficiaries from unemployment benefit programmes to other programmes such as ‘renta activa de inserción’ (active insertion income), which is aimed at unemployed persons facing economic hardship who agree to take part in labour integration programmes (or the activation for employment programme) aimed at the long-term unemployed.

Such as, for example, training public administration staff, publicising legislation, ministerial transport, managing national assets, preparing and publishing statistics, elections and political parties, etc.

This new item includes, among other expenses, expenditure on economic forecasting, the public accounts, application and management of the taxation system, management of the property register, and resolution of economic/administrative complaints.

References

EUROSTAT (2014), Taxation trends in the European Union. Data for the EU Member States, Iceland and Norway, Luxembourg.

MINISTERIO DE HACIENDA Y ADMINISTRACIONES PÚBLICAS [MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION] (2015), Presentación del Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales de Estado 2016 [Presentation of the draft General State Budget 2016], Ministerio de Hacienda [Ministry of Finance], Madrid.

MINISTERIO DE INDUSTRIA, ENERGÍA Y TURISMO [MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY, ENERGY AND TOURISM] (2015), Retrato de las Pyme 2015 [Portrait of SMEs], Dirección General de Industria y de la Pequeña y Mediana Empresa [Directorate General for Industry and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises], Madrid.

SANZ, J. F., and D. ROMERO (2014),”Principales rasgos de los Presupuestos Generales del Estado para 2015.” Cuadernos de Información Económica, 243, pp. 13-23.

Desiderio Romero-Jordán. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

José Félix Sanz-Sanz. Universidad Complutense de Madrid