Cleaning up the Spanish financial sector´s real estate risk exposure: Situation and outlook

Spain´s property market is showing signs of stabilisation after the crisis. At the same time, the process of reducing the financial sector´s real estate risk is gaining momentum through the adoption of various deleveraging strategies, together with the help of new players in Spain´s property market.

Abstract: Recent indicators point to a stabilisation in Spain´s real estate market, with an increase in house prices as well as sales, albeit from a low starting point. In this context, banks are prudently reducing exposure to real estate and construction lending, which reached 50% of total credit to productive industries at its peak, while at the same time moving forward on cleaning up real estate assets. Initial risk reduction strategies have included loan refinancing and restructuring operations, together with foreclosures, which ended up significantly increasing the number of properties held on Spanish financial institutions´ balance sheets. Subsequent phases of deleveraging included the sale of non-strategic assets and businesses, such as real estate platforms, where institutions concentrated their foreclosed assets, alongside the sale of loans and foreclosed assets themselves. Finally, at a later stage of the process, banks opted to reduce their stock of foreclosed properties through land development initiatives. Going forward, major players, like the SAREB, and new entrants, such as the Real Estate Investment Companies (the SOCIMIs in their Spanish initials), will also play a key role in the ultimate success of the reduction of Spanish banks´ property market exposure and risk.

This article presents an analysis of the status and outlook for the reduction and restructuring of Spanish financial institutions’ property risk. The property market expansion which lasted from early 2000 until 2007 significantly increased the Spanish banking sector’s concentration of risk in construction and other real estate activities. At the peak of this process, 50% of deposit-taking institutions’ lending to productive activities was concentrated in the construction and real estate sectors. When the volume of mortgages for home purchases is also considered, the exposure in 2007 reached a trillion euros. Since the onset of the financial crisis, there has been a significant contraction in financing for construction and real estate activities as a share of total lending to the productive sector, although this process only really gained momentum in late 2012. This article reviews the process of reduction of the real estate exposure that Spanish financial institutions have undergone in recent years. To contextualize this process, the first section describes the situation of the Spanish real estate sector. The second section provides basic facts on Spanish financial institutions’ property market deleveraging and the main strategies employed in reducing banks´ property risk. The article then provides some concluding remarks.

The property market context

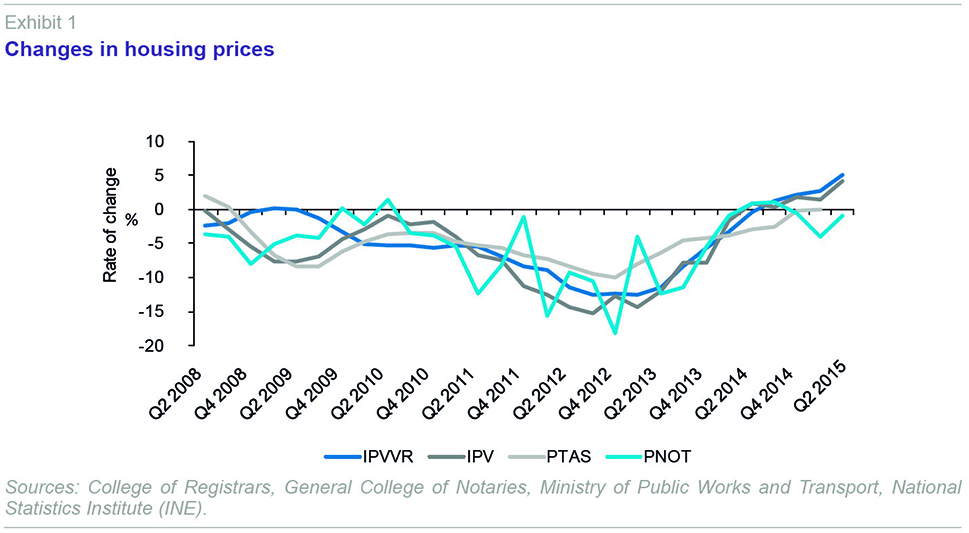

With the slowing of demand for housing and the onset of the financial crisis in Spain, the real estate sector embarked on a painful adjustment that began with a rapid slowdown in property transactions and new housing starts, but with no significant drop in prices. Prices really began to fall in late 2011 and the process accelerated in 2012 and 2013 causing cumulative proportional losses similar to those in other countries (between 30% and 45%, depending on the price index used). Developments in the financial sector played an important role in this slow initial drop and faster decline as of 2012, as will be discussed below.

As can be seen from Exhibit 1, prices stabilised in late 2014 and began to rise steadily in the first half of 2015. The IPVVR (College of Registrars Index of prices of repeated sales) indicates a rapid price rise in the second quarter of 2015, reaching a rate of 5.1%. Using the same underlying data,

[1] the IPV (INE house price index) shows a slightly more moderate picture, although with a rise of 4.2% at the end of June. The Ministry of Public Works and Transport’s appraisals price index (PTAS) shows a complete stabilisation during two quarters and a small increase (1.2%) in the second quarter of 2015. It is worth noting that unlike the situation during the property boom, when valuations were inflated due to the perverse incentives in mortgage financing (Montalvo and Raya, 2012), decrees enacted in 2012 placed restrictions on the ownership of appraisal companies, causing the opposite to happen, and valuations now tend to underestimate the value of real estate collateral. Lastly, the General College of Notaries’ price index (PNOT) continues to register a drop, albeit a moderate one.

Another important factor in characterising the situation of the Spanish real estate sector is the change in the stock of unsold new housing. The stock is diminishing, but very slowly. According to the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, the stock reached 536,000 units at the end of 2014, with an annual reduction of just 5%. Other estimates increase the stock up to 700,000 units. Many of these homes are located in areas where there is no demand and is unlikely to be any for many years to come. Some estimates situate this share at around 30%. Nevertheless, the rate at which the excess stock of new housing is disappearing has until now been slow, despite the recent increase in sales. García Montalvo (2012) also shows there to be a close correlation between the price drop and the stock of unsold new housing in each province.

In short, the real estate sector is still recovering from its slump. The situation in the sector and the outlook for its future development are of considerable importance in financial institutions’ strategies for the management of their property risk exposure. Housing sales are rising by 13%, although prices remain relatively stable, even though some indicators already suggest significant increases.

[2] These expectations of improvements in the sector, in particular of future price increases, have led to a debate over whether financial institutions have slowed the rate of their sales of housing while they wait for higher prices. What is clear is that, although the signs are positive, we are still a long way from an excessive expansion in the real estate sector. Many of the sector’s indicators are growing at double-digit rates, nevertheless it seems that the real estate sector is simply returning to normality after a few years of stagnation. Housing sales are rising at slightly more than 10%, but the number of transactions in the first quarter of 2015 was just 41% of that in the first quarter of 2007. New housing starts grew by 15%, but the total number of building permits is only 5% of those issued during the boom. The construction sector and real estate services have created 125,000 jobs over the past year, but they have shed 1.7 million jobs since the start of the crisis. Employment in the sector has dropped from 14% of the total to 7%. And despite the price increase in the last six months, prices are still 33% below their peak. Therefore, the latest property market indicators do not justify talk of a new property boom, but rather a stabilisation.

The evolution of real estate risk exposure in the banking sector

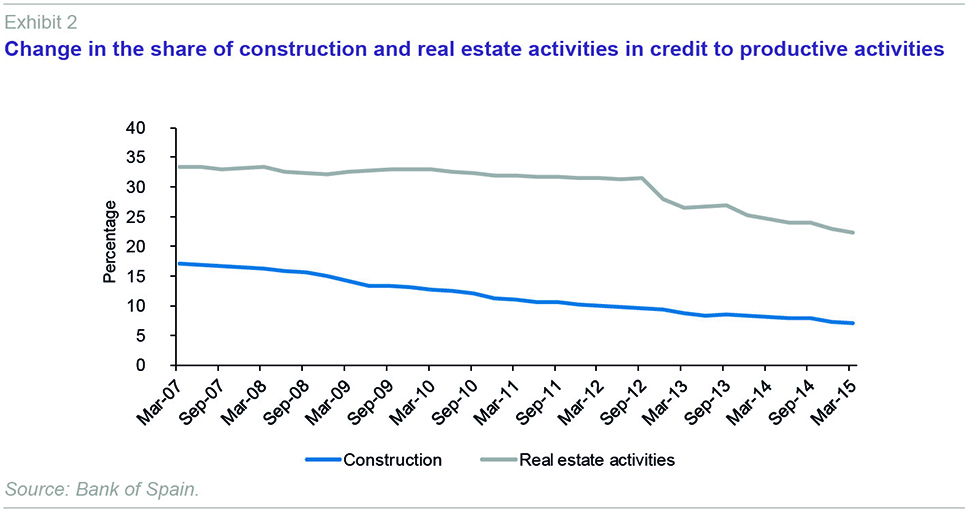

At its peak, the construction and real estate services sector came to concentrate 50% of Spanish deposit-taking institutions’ total credit to productive activities. Since the start of the financial crisis, this proportion has been falling, albeit at different rates in the two sectors. The reduction is explained both by banks’ desire to reduce their property risk and the commitments made by nationalised institutions in their restructuring plans, which included limits on their exposures to construction firms and property developers.

Exhibit 2 shows how the share of lending to construction and real estate activities in Spanish deposit-taking institutions’ credit to productive activities has changed. Lending to the construction industry contracted rapidly with the onset of the property crisis. From 150 billion euros in June 2008 it dropped to 100 billion in September 2011. The reduction in lending for real estate activities was much slower. Indeed, it continued to accumulate up until June 2009, peaking at 320 billion euros. In September 2011, lending for real estate activities still stood at 300 billion euros. 2012 marked the start of the significant drop in property risk exposure. In March 2015, lending to construction firms and for real estate activities accounted for 29% of total lending to productive activities, at around 190 billion euros, having dropped by 21 points since its peak. This implies that at its peak, 40% of lending was for construction and real estate activities.

[3]

Lending to households to finance home purchases has also dropped, but to a much lesser extent (13%) and is still at 87% of its peak during the expansion. Overall, lending for construction and real estate activities, and to households to finance home purchases, came to around 100% of GDP in 2008. By March 2015 this proportion had dropped to 70%.

This process underway in the financial sector could be described as a creative destruction of credit, as there is a reorientation of credit towards more productive firms, operating in more dynamic sectors, with higher profits and less debt (Bank of Spain, 2014). It is worth bearing in mind that part of the decline in loans of more than a million euros to non-financial corporations, which is the only segment in which new credit operations are not growing, is due to the substitution of bank financing with resources from the fixed income market or loans from abroad. There is a significant upturn (22%) in the granting of new home loans to households, although total lending for home purchases and refurbishments continued its decline, at a rate of 4.3% at the end of March. The growth in the granting of new loans coincides with an improvement in the Spanish economy’s indicators and growing competition among financial institutions to give mortgages. While it is true that price competition is intense, with spreads that have dropped to around a point or one and a half points, it is also true that this competition does not seem to have extended to loan approval criteria. The data shows that mortgages are granted mostly to workers with an open-ended contract (78%), while at the end of the housing bubble that proportion was only 52%. However, it is true that the average loan to value of new mortgages has increased since 2013 moving from 66% to around 72%.

Evolution of the default rate of real estate exposure

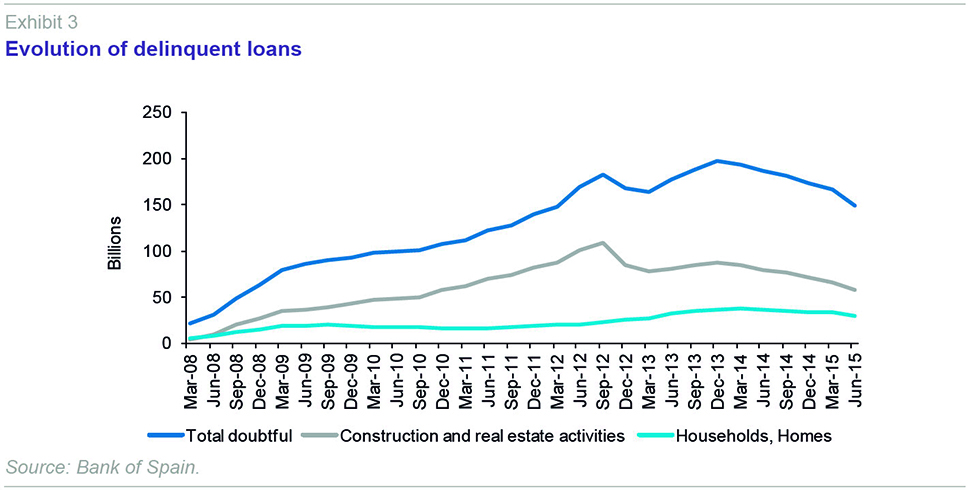

When analysing the process of cleaning up the real estate risk exposure on banks’ balance sheets, it is important to look at how the default rate has changed by individual segments. The delinquency of the portfolio of loans to the resident private sector dropped by 24 billion euros in 2014, this being the first year since the start of the crisis in which this trend has been observed.

The reduction in the delinquency rate was generalised among institutions, with the dispersion narrowing compared to the preceding year (Bank of Spain, 2015.) Exhibit 3 shows the evolution of Spanish financial institutions’ non-performing loans. Exhibit 3 has at least three distinct phases. The first phase is characterised by a significant increase in the balance of defaults up until late 2012. The transfer of loans to SAREB is reflected in the drop in defaults at the end of 2012.

[4] In early 2014 a reduction in the volume of delinquent loans began, and this can also be clearly seen in the lending to the construction and real estate sector. This reduction in delinquent loans was the result of various processes. A portion of the non-performing loans was written-off, while another portion has been “cured” returning to performing status. Sales of portfolios of non-performing loans and shares in real estate firms, together with the cancellation of debts arising from property foreclosures also reduced the volume of loans classified as non-performing, although the latter case, does not, strictly speaking, reduce the risk exposure to the real estate sector. The evolution of the NPL rate shows a less pronounced drop than in the absolute values due to the contraction in total credit, although the trend has accelerated during 2015 moving from 12.51% in December of 2014 to 10.93% in June of 2015. Secondly, the delinquency rate for construction companies and real estate activities, which peaked at 37% in December of 2013, has dropped to 31.7% at the end of June 2015, although it remains very high. The delinquency rate for home mortgages of households was 5.45% at the end of June 2015.

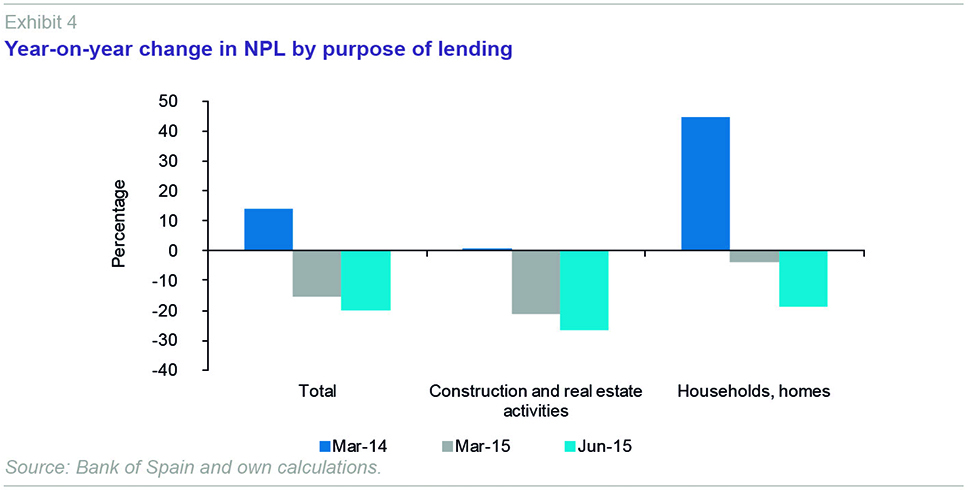

In order to analyse recent changes in default rates, Exhibit 4 shows the year-on-year change in the rate of doubtful assets by purpose of lending. Total defaults rose by 13.8% in March 2014 while they dropped by 19.9% in June 2015 with respect to June of 2014. The bigger drop in defaults corresponds to lending to construction companies and real estate activities, which reduced their doubtful loans by 26.7% (almost three times the rate of the drop in other lending to non-financial corporations). Doubtful loan rates for households to finance home purchases rose rapidly in March 2014, with a slight year-on-year drop in March 2015 to 3.6% and a faster reduction in June 2015 (18.6%).

Refinancing and restructuring of property risk

During the early stages of the crisis, financial institutions resorted to refinancing many loans. For this reason, one interesting dimension of how the clean-up of Spanish banks’ real estate exposure has progressed is an analysis of how refinancing and restructuring have evolved. As a result of the Memorandum of Understanding signed with the EU by the Spanish authorities, measures were taken to improve the information available on refinancing and restructuring operations. Bank of Spain Circular 6/2012 defines both types of operations precisely and obliges banks to report their amounts, risk classification (normal, substandard or defaulted) and their purpose and coverage. In December 2013, the amount of refinancing and restructuring reached 211 billion euros, loans for construction and real estate activities representing 27% of the total and loans to households for home purchases a further 27%. In December 2014 total refinancing and restructuring came to 201 billion euros, with loans for construction and real estate activities representing 22.6% of the total and loans to households for home purchases a further 25.9%. Among the refinanced loans to the construction and real estate sectors, 75% were classified as doubtful and 13% as substandard. In the other sector, loans to households for home purchases and refurbishments, 39% were doubtful and 15% substandard.

Foreclosed real estate assets

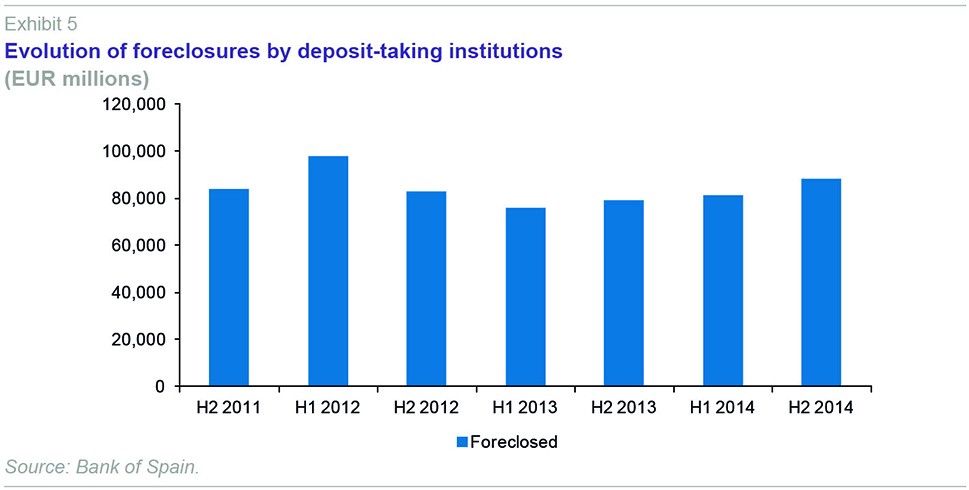

Another important component of Spanish financial institutions’ property risk exposure is the foreclosure of real estate assets. Since the start of the financial crisis, foreclosures have significantly increased the number of properties on Spanish financial institutions’ balance sheets, bringing the gross total to almost 100 billion euros in the first half of 2012 (Exhibit 5). Subsequently foreclosed real estate assets worth 32.2 billion euros (gross value) from the entities in Group 1(BFA-Bankia, Catalunya Banc, NCG Banco-Banco Gallego and Banco de Valencia) and Group 2 (BMN, Ceiss, Liberbank and Caja3) were transferred to SAREB, which explains the drop in foreclosures observed in the second half of 2012

[5] and in the first half of 2013.

[6] In total, SAREB received 107,446 real estate assets with a value at acquisition cost of 11.34 billion euros.

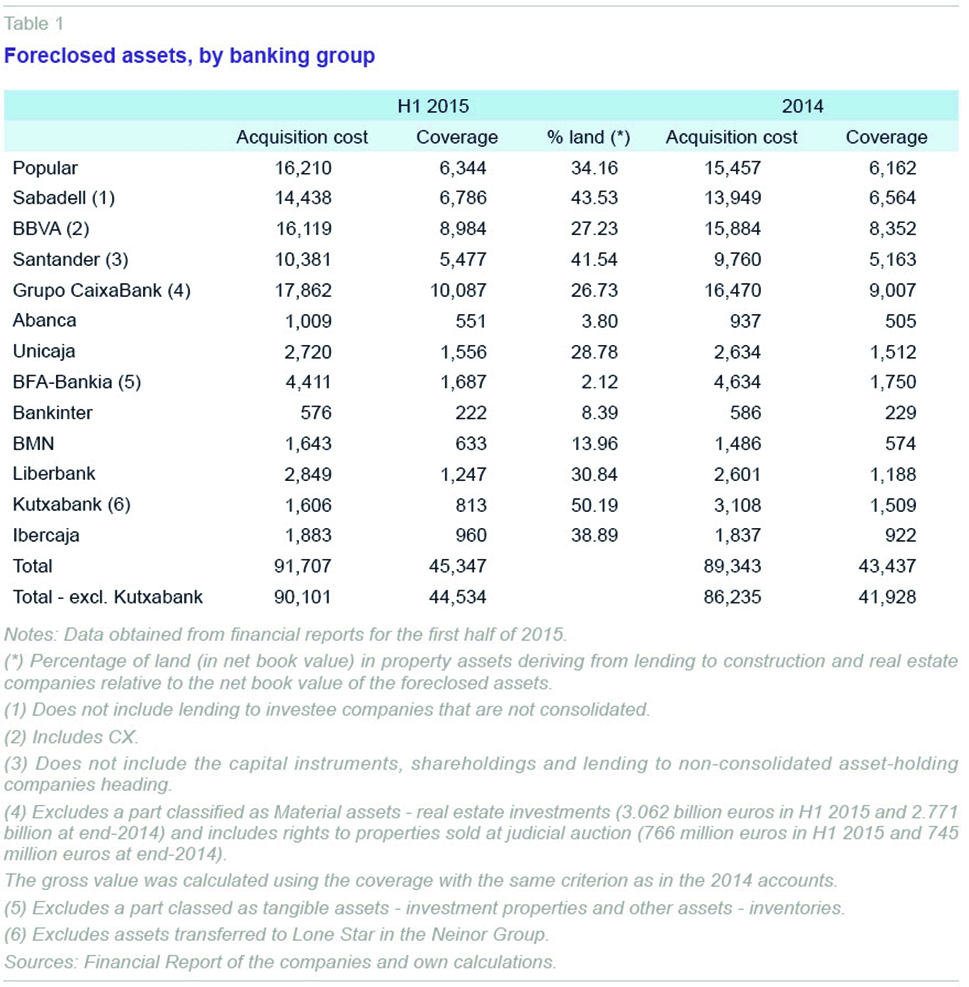

[7] Spanish financial institutions continued to accumulate foreclosed properties even after the transfer of assets to SAREB, and as Table 1 shows, the growth trend in foreclosed assets persisted into the first half of 2015. However, it is difficult to summarise the data on different institutions’ foreclosures as, although in theory, there is a uniform format in which this information is to be presented, some institutions have changed the classification criteria for some foreclosures or present data incompatible with that in the 2014 financial report. Table 1 gives estimates for cases in which no straightforward comparison of the six-monthly data and the data in the 2014 annual report is possible. In most cases, we have opted to maintain the information from the comparison between the first half of 2015 and December 31st, 2014, as shown in the report from the first half of 2015.

Table 1 shows that the accumulation of real estate assets on entities’ balance sheets continued into the first half of 2015. Eliminating the influence of the transfer of Neinor Group to Lone Star, which affects the aggregate comparison as it took place during the first half of 2015, a significant increase in foreclosures has been observed. The analysis of the distribution of foreclosures by asset type shows that land accounts for the largest share, reaching a sector average of 38%. Land foreclosures as a proportion of the total vary considerably from one entity to another. Abanca and BFA-Bankia have the lowest proportions (due to the transfer to SAREB), along with Bankinter. Banco Sabadell (due to the impact of its taking over foreclosed land from the former CAM) and Kutxabank (due to the distribution of assets transferred in the sale of Neinor Group to Lone Star) have the largest proportions. Average coverage of foreclosed assets is 49.4%, although again there are considerable differences between entities. Provision coverage is in the range of 38% to 55%.

Real estate platforms

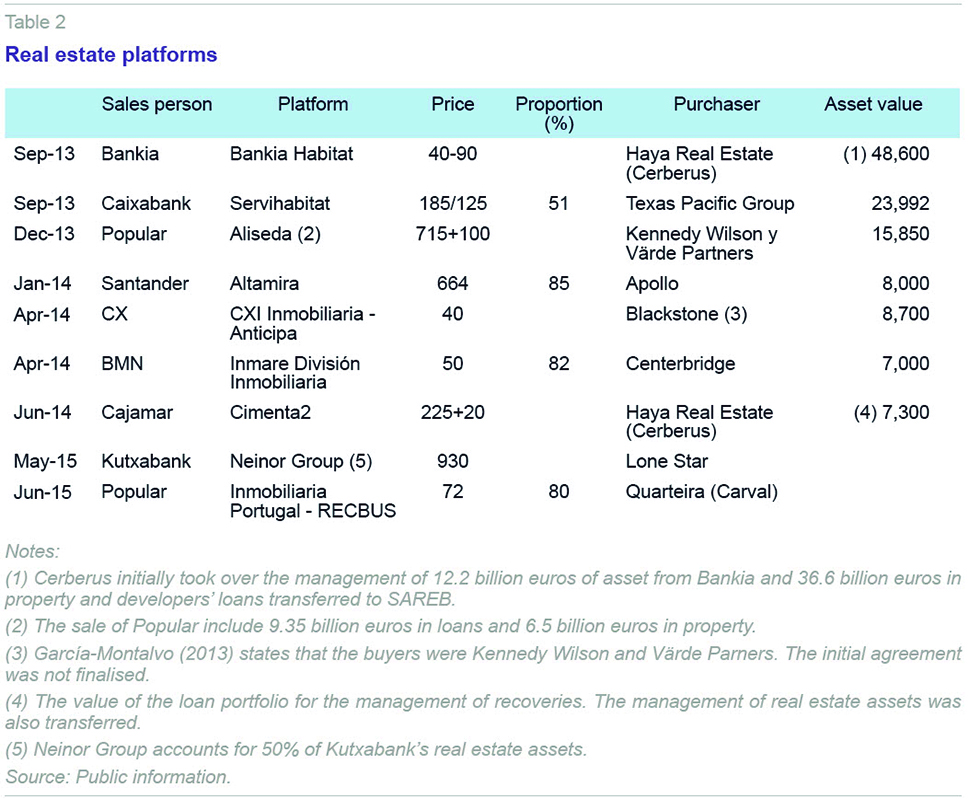

After rapid initial growth in refinancing and restructuring and foreclosures of property, there was a second phase more focused on transferring non-strategic assets and businesses. This process included transferring the administration and management, or the ownership, of banks’ real estate platforms, the sale of foreclosed assets, and the sale of loan portfolios. More recently there has been a conversion of land in prime locations into housing developments, which may be turned into new mortgage lending.

One of the strategies pursued to reduce property risk has been the transfer, whether voluntary or obligatory under the terms of restructuring plans, of the administration and management, or the ownership, of the real estate platforms where institutions concentrated their foreclosed assets. Table 2 shows the most significant operations. Some of these operations were linked to the management of assets transferred by financial institutions in Groups 1 and 2 to SAREB.

[8] The last major operation was Lone Star’s purchase of Neinor Group (Neinor, Inverlus, CajaSur Inmobiliaria and Valle Romano). With the sale of these platforms there are only two financial institutions that are still managing real estate platforms of a significant size: BBVA (Anida) and Banco Sabadell (Solvia). The conditions of the initial transfer of the management of the assets on some of these platforms were altered by SAREB’s change in its strategy for managing its products. This culminated in the assignment of new so-called “servicers” for its financial and real estate assets as a result of the Ibero project, described below. The future of these platforms involves their consolidation, a process that has begun with the sale of some debt-collection and real estate platforms, but has not yet reached the necessary scale. Moreover, some of the funds that invested in real estate platforms have taken part successfully in the Ibero project and have continued to buy real estate assets and loans to gain volume and improve asset management efficiency.

Sale of loans and foreclosed property

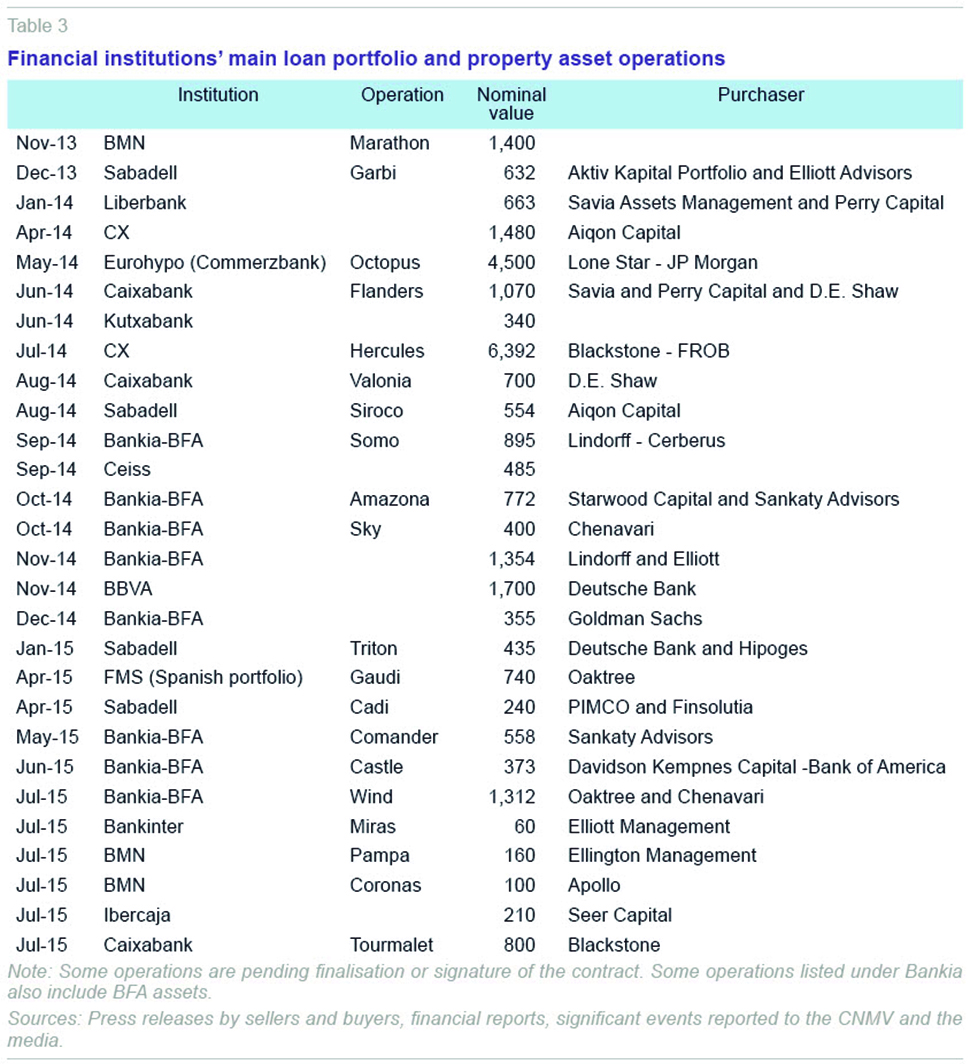

Another mechanism for reducing the weight of real estate risk exposure on the financial sector’s balance sheet is the sale of loan and property portfolios. Selling these assets is a quick way of cleaning up the portfolio of non-productive assets. Sales of this kind have taken place in all countries during the process of cleaning up the financial sector. According to PWC (2015), sales of loans in Europe totalled 91 billion euros in 2014, an increase of 40% on the preceding year,

[9] and are projected to reach 140 billion in 2015. In the United Kingdom alone, 88 billion euros worth of loans were sold between 2010 and the end of the first half of 2015. In Ireland, the total came to almost 60 billion euros over the same period, while in Spain, it was just over 50 billion euros. In the Spanish case, investment funds initially came on the scene buying debt-collection platforms. Lindorff bought Banco Santander’s debt-collection platform (Reintegra) and Centerbridge bought Aktua from Banesto, although it soon began to buy loan portfolios,

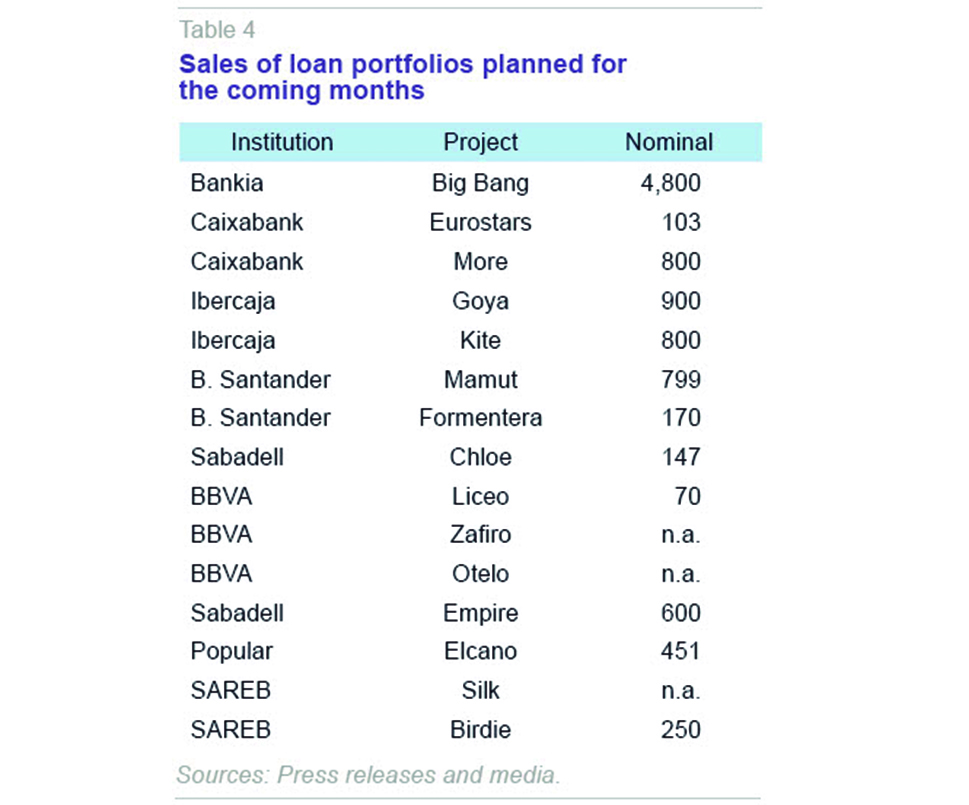

[10] often associated with real estate collateral. Table 3 shows the main loan portfolio sales since late 2013 (including portfolios comprising only written-off loans). The list does not include subsequent sales of assets bought from financial institutions. For example, in June 2014, Lindorff bought two billion euros worth of NPLs that had originally belonged to Santander, which had previously sold them to Fortress (Luna project) and TPG (one billion in loans inherited from when it took over the Octavia fund in 2013). Nor does it include the sale of real estate holdings (commercial or hotels), such as Banco Santander’s sale in May 2015 of a stake in NH, or the sale of interests in syndicated loans. Group 1 entities, in particular Bankia and Catalunya Banc, have been the most active in the sale of loan portfolios as part of the divestment of non-strategic assets as a result of the commitments made by the Spanish authorities to obtain the European Commission’s approval of their respective restructuring plans (“Terms Sheets”). The most significant operation was the transfer of Catalunya Banc’s Hercules portfolio, with a nominal value of 6.392 billion euros, to an asset securitisation fund (ASF) for its book value in the entity (4.187 billion euros), where Blackstone contributed 3.615 billion and the FROB 572 million. This highly complex operation involved three subportfolios and five tranches and attracted interest from almost all the funds investing in the Spanish loan portfolio market. Table 4 lists the loan portfolio sale operations announced but not completed. These include Bankia’s “Big Bang” project (4.8 billion), which is currently the second largest portfolio

[11] up for sale.

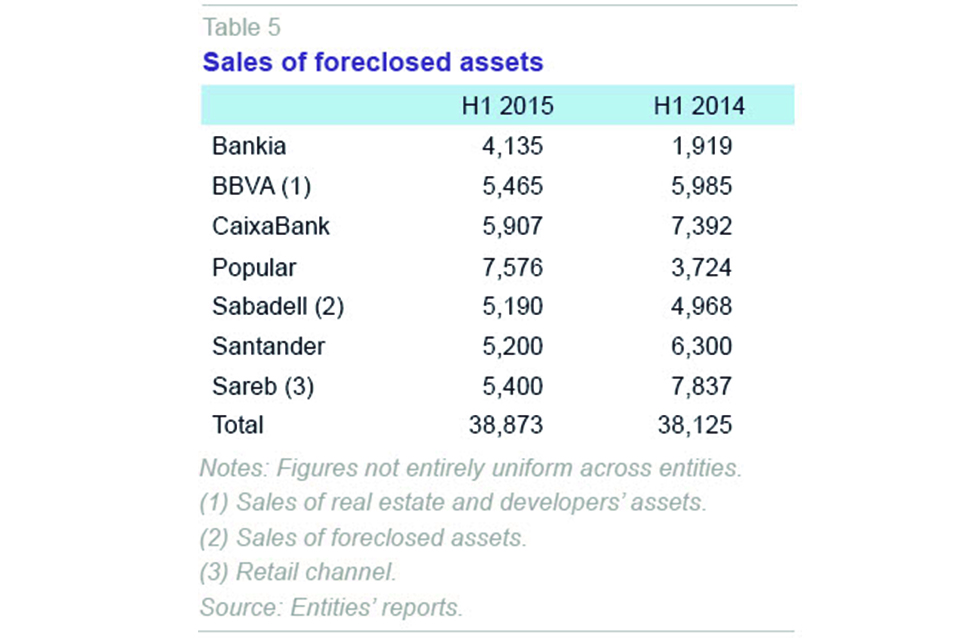

Selling off foreclosed assets is another mechanism which banks can use to clean up the real estate exposure on their balance sheets. Table 5 shows housing sales by the main real estate platforms between the first half of 2014 and the first half of 2015.

[12] Despite the difficulties of comparing entities due to the differences in their calculation criteria, in general a small increase in sales can be seen, with a significant increase in the pace by some entities (

e.g., Bankia and Banco Popular), and a slowdown by others. Information about the prices at which these real estate assets have been sold is scarce. In its financial reports, Banco Popular merely states that it is selling its foreclosed properties at prices close to their book value, and therefore avoiding losses. Banco Sabadell is more explicit, and states that the average discount on the gross value of the sale of its foreclosed properties was 60.4% in the first half of 2013, 52.4% in the first half of 2014, and 46.4% in the first half of 2015.

The emergence of certain price tensions in some localities has given rise to controversy over the possibility that some financial institutions were applying a strategy of waiting for prices to rise further before stepping up sales again. Housing sold by the banks accounted for 24.5% of the total housing sales registered in the first quarter of 2014, while in 2015 this percentage had dropped to 23%.

Another way of stimulating the process of reducing the stock of foreclosed properties is to develop the stock of land that financial institutions hold. This is the third phase mentioned earlier. The high level of provisions of these assets implies they have a limited impact on the final housing price, which therefore ensures that the new housing is competitively priced. These new developments would obviously be on land in areas in which demand is strong. Many entities have announced they plan to develop the land they hold. Neinor’s projection is to build around 3,000 homes a year. BBVA has announced 2,000 new homes and Solvia 1,000. SAREB has 1,109 homes in progress as a result of developing 13 plots of land.

SAREB and the new “servicers”

SAREB is a key player in the cleaning up of the Spanish real estate market risk exposure. SAREB’s portfolio was valued at 44.2 billion euros at the end of 2014. Real estate accounted for 13% of the value of the foreclosed properties on the balance sheet of the banks. The loans on SAREB’s balance sheet amount to 50% of the non-performing loans to construction and real estate activities of the financial institutions. SAREB began its activity in 2012 when it took over the assets of the financial institutions referred to as Group 1. When it took over the assets of Group 2 on February 28th, 2013, SAREB completed a portfolio of 50.781 billion euros (at acquisition cost) including financial assets (78%) and real estate assets (22%). Over the period 2013-14 it sold 24,000 properties, undertook 25 wholesale operations, and obtained total income of 9 billion euros. By end-2014 it had amortised 5.7 billion euros of debt from its balance sheet.

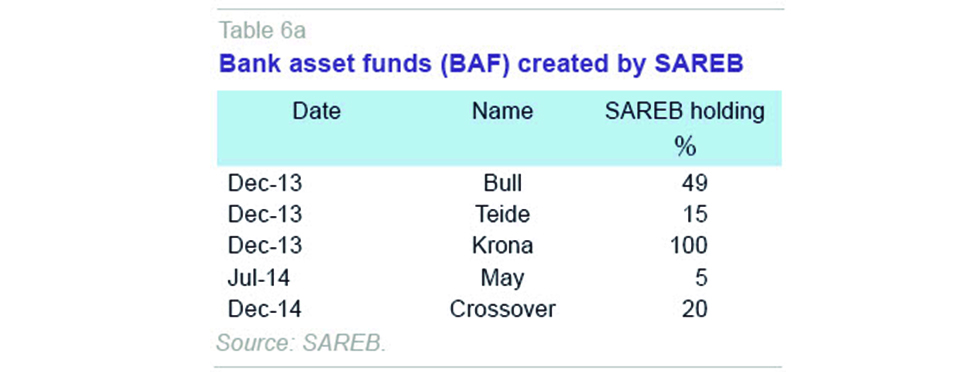

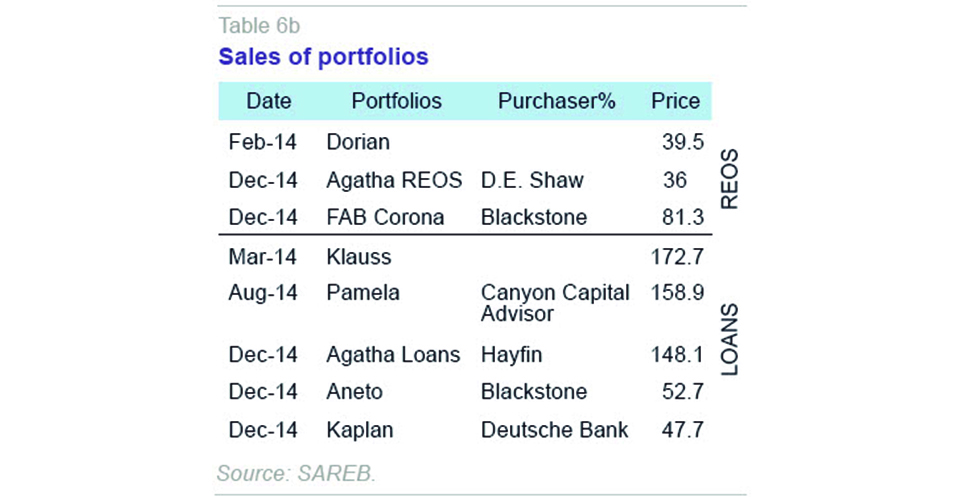

In 2014 SAREB sold 15,298 properties via its retail channel, with a significant increase in the contribution from the sale of land (rising from 15% in 2013 to 26% in 2014) and a reduction in the contribution of residential property sales (from 80% in 2013 to 63% in 2014). As regards the retail lending channel, there has been a significant increase in the number of sale promotion plans, with 5,278 proposals managed (45.6% of the total proposals including dations in payment and foreclosures, and restructuring and refinancing) and 800 plans. It is worth noting that the retail channel generated 80% of SAREB’s income of 5.115 billion euros in 2014. Income from the wholesale channel, 1.115 billion euros, was concentrated in December 2014 (708 million euros) (SAREB, 2015). Table 6.a shows the bank asset funds (BAFs) created by SAREB since it began operating, and its stake in them. Table 6.b lists the portfolios and BAFs sold by SAREB in 2014, both of REOS (Real Estate Owned by lenders) and loans.

[13]

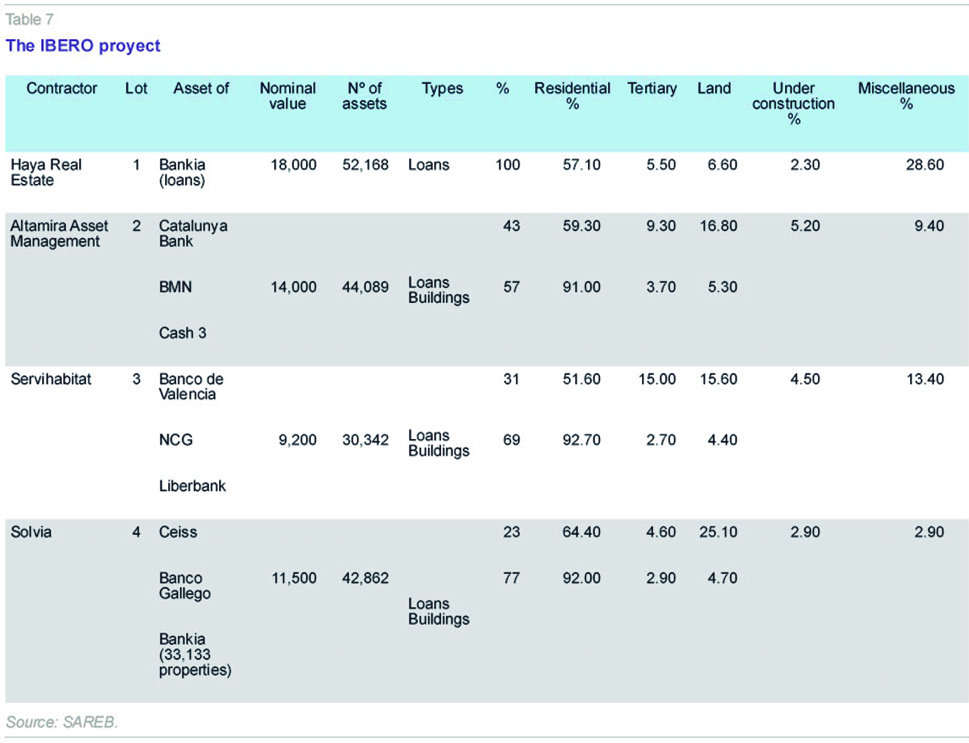

Since coming into operation, SAREB has been caught up in various controversies concerning the feasibility of the business plans it has presented, possible conflicts of interest on its board of directors, and various changes to its top executives and corporate structure. It has also been criticised for its management style, which on occasions is somewhat authoritarian, bureaucratic and inflexible in its asset management contracts. Perhaps the most significant recent event has been the change in the system for assigning so-called “servicers” in charge of the administration and management of its assets. Annual agreements were initially signed with the real estate platforms of certain entities that had transferred their assets for the administration and management of SAREB’s assets. In 2014, SAREB launched the IBERO project to select the managers for the administration and sale of the company’s assets as of January 1

st, 2015. Table 7 shows the results of the process of awarding the asset management contract. In the first round, Solvia was put in charge of the assets in block 4, comprising loans and property transferred by Ceiss and Banco Gallego, and the property transferred by Bankia. The second round was concluded with the selection of Haya Real Estate, Altamira Asset Management and Servihabitat. This means that since end-2014, Blackstone and Centerbridge, which had acquired the Catalunya Banc and BMN platforms, respectively, are no longer managing SAREB assets.

The emergence of the SOCIMIs

Spanish property consulting group CBRE estimates that sales of offices, shopping centres, logistics centres, hotels, and residential assets totalled 8.434 billion euros in the first half of 2015.

[14] As discussed above, financial institutions, international funds and SAREB are currently the leading players in the Spanish real estate market.

[15] However, over the past year, other players have gained a more central role: Real Estate Investment Companies (Sociedades Anónimas de Inversión en el Mercado Inmobiliario, SOCIMIs). SOCIMIs are regulated by Law 11/2009, as amended by Law 16/2012, and are obliged to invest at least 80% of their asset value in urban real estate intended for lease or in land for the development of property for subsequent lease provided that development is begun within three years of acquisition. Moreover, at least 80% of their income, excluding that derived from the sale of holdings or of properties once the retention period (3 years) has elapsed, must draw from the lease of property and dividends or shares in the profits on these stakes. One of the big attractions of these companies is their tax treatment: their corporate tax rate is 0% except when the dividends they distribute to one of the partners holding a stake of more than 5% are taxed at less than 10%, in which case they pay a special tax of 19%.

SOCIMIs must be listed on Spanish or other European markets. After the amendment of the law in 2012, the minimum capital required has dropped from 15 to 5 million euros, and the restriction on the maximum debt of the investment vehicle has been eliminated. They are also subject to strict rules on the obligatory distribution of dividends from rental income and the transfer of properties and company holdings: as of January 1st, 2013, the obligation is for 90%.

There are currently 21 real estate companies on the Madrid Stock Exchange, although some of them, such as Martin Fadesa or Reyal Urbis, are currently suspended from trading. The majority of new investments, totalling almost 5 billion euros, have been in SOCIMIs (Axiare Patrimonio, Lar España Real Estate and Merlin Properties) and Hispania Activos Inmobiliarios.

[16] The biggest of the SOCIMIs is Merlin Properties, which was first listed on June 30

th, 2014, with a capital of 1.25 billion euros. Since then, it has increased its capital by 614 million euros and is preparing another capital increase of 1.034 billion euros to enable it to take over Testa Inmuebles en Renta SA from SACYR. Together with these SOCIMIs listed on the Madrid Stock Exchange, there is also URO Property Holdings SOCIMI (listed on MAB) which owns 755 offices it leases to Santander, and Saint Croix Hoding Immobilier SOCIMI, based in Spain but listed in Luxembourg.

Concluding remarks

The property crisis hit the Spanish financial system at a time when it had a huge exposure to the property market. This exposure was initially reduced only slowly. In 2012, the process of cleaning up the banking sector gained momentum, with the sale of non-strategic assets such as debt-collection firms and real estate platforms. In its second phase the process developed with the sale of portfolios of problematic loans, shareholdings in real estate businesses, interests in syndicated loans, or individual loans, and included real estate companies with financial difficulties, and the sale of foreclosed assets. While the sale of loans is significantly reducing entities’ property risk,

[17] sales of property are progressing more slowly, such that the stock of foreclosed properties continues to grow. In the third phase, which began in late 2014, some financial institutions have slowed the pace of property sales and are trying to mobilise foreclosed land, which represents a large share of foreclosed real estate. They are therefore initiating property developments in locations where demand is strong, so as to convert these hard to realise assets into future mortgages.

Notes

The IPVVR uses a repeat sales methodology to harmonise the quality of homes included in the calculation of the index, while the IPV uses hedonic methods.

The indicators that reflect significant growth rates undoubtedly place more weight on cities such as Madrid, and particularly Barcelona, where there is more pressure on prices.

Correcting for the transfer of loans to SAREB, the contraction would be 50%.

Institutions in Group 1 and 2 transferred 90,765 financial assets with a net value of over 250,000 euros, for a total value of 39.44 billion euros (gross value of 74.74 billion euros).

The date on which assets of Group 1 entities were transferred was December 31st, 2012.

The official date on which assets of Group 2 entities were transferred was February 28th, 2013.

Gross value of 32.22 billion euros.

The progress of SAREB and the IBERO project will be discussed below.

This document estimates that investment funds have over 70 billion euros to invest in assets sold by European banks.

They normally comprise non-performing and written-off loans, or a combination thereof. In some cases they may also include “performing” loans. The sale of written-off loans does not reduce the NPL rate as they are off the balance sheet, but it does directly improve the profit and loss account.

The largest is operation Arrow of Nama (8.4 billion).

The two entities’ data are not uniform as some also include sales of developers’ properties corresponding to PDVs (Planes de Dinamización de Ventas or agreements of banks with creditors in the construction and development business to accelerate the liquidation of their real estate properties) and others do not.

Three operations were concluded in 2013, referred to as Elora, Abacus and Bermudas.

Including the purchase of the real estate company Testa.

Alongside these entities are companies such as Ponte Gadea, which are highly active in asset purchases in both Spain and elsewhere, and investors such as Carlos Slim.

The new SOCIMIs Gmp and Zambal are likely to be floated on the stock market in late 2015.

2015 could be a record year for this type of transaction.

References

BANK OF SPAIN (2014), Annual report 2014: pages 126-131.

— (2015), Financial Stability Report, May 2015.

GARCÍA MONTALVO, J. (2012), “Perspectivas de precios de la vivienda en España,” (Outlook for housing prices in Spain), Cuadernos de Información Económica, 227: 49-59.

— (2013), “The Spanish housing market: Is the adjustment over?” Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 2 (5), September: 15-26.

GARCÍA-MONTALVO, J., and J. RAYA (2012), “What is the right price of Spanish residential real estate,? 1 (3), Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, September: 22-29.

PWC (2015), Portfolio Advisory Group, Market update Q4, 2014.

SAREB (2015), Annual report 2014.

José García Montalvo. Professor of Economics, Universitat Pompeu Fabra