Institutional reforms: A source of productivity gains for the Spanish economy

Spain’s declining total factor productivity is partially attributed to institutional weaknesses in areas such as transparency, the justice system, regulation, and government coordination. If left unaddressed, it could undermine Spain’s successful transition to the digital/green economy.

Abstract: Between 1996 and 2017, total factor productivity in Spain decreased by 10.5%. Some evidence suggests that certain institutional weaknesses could be a direct cause of the unsatisfactory trend in productivity. For example, the Global Competitiveness Report shows that Spain ranks 23rd on institutional quality compared to higher rankings in areas such as health and physical infrastructure. Notably, Spain is one of the EU countries in which institutional quality has deteriorated the most over the past two decades. This is likely due to the real estate boom and period of sustained growth in abundant and cheap credit during the run up to the financial crisis. Upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that Spain’s institutional deficiencies are especially acute in areas such as transparency, the justice system, regulation, and coordination between government levels, which weigh on the country’s economic growth. However, one bright spot for Spain is the quality of its democracy, with the country continuing to fall within the Economist Intelligence Unit’s group of “full democracies”. In light of the COVID-19 crisis and the transition to a digital/green economy, it is especially pressing that Spain address its institutional vulnerabilities. If left unaddressed, the absence of government efficiency could undermine Spain’s response to the upcoming changes anticipated in the international economy.

Introduction

There is a body of literature attesting to the important role institutions play in supporting productive efficiency and economic growth. This paper seeks to apply that idea to the Spanish economy, which has been suffering from low productivity, a phenomenon that has worsened during the last 20 years.

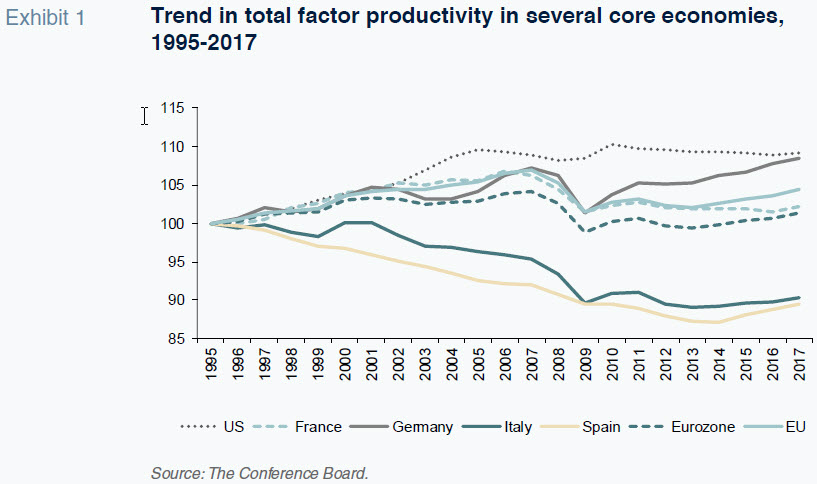

Between 1996 and 2017, total factor productivity (TFP) in Spain decreased by 10.5% (albeit recovering slightly since 2014), compared to growth of 4.5% in the EU as a whole (according the BBVA Foundation and The Conference Board; refer to Exhibit 1).

[1] As a result, the gap with the core EU economies has widened significantly, signalling an potential impediment to Spanish economic growth in the long- term.

To explain this phenomenon, analyses has focused on certain key factors. These include low investment in innovation, human capital deficits, and the outsized weight of micro enterprises in the Spanish economy. There are also indications that certain failures in the economy’s institutional infrastructure could be a direct cause of the unsatisfactory trend in productivity.

Until recently, analytical progress has been hampered by the difficulty of measuring ‘institutional quality’. However, during the last 20 years, some international organisations have attempted to quantify variables such as accountability, political stability, government effectiveness and the clarity with which property rights are defined. This has provided a deep database and web of indicators relevant to assessing the efficiency of a given institutional structure. These databases include the Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) by the World Economic Forum, Doing Business (DB) and the Worldwide Governance Indicators, both by the World Bank Group.

The Spanish economy: Institutional infrastructure

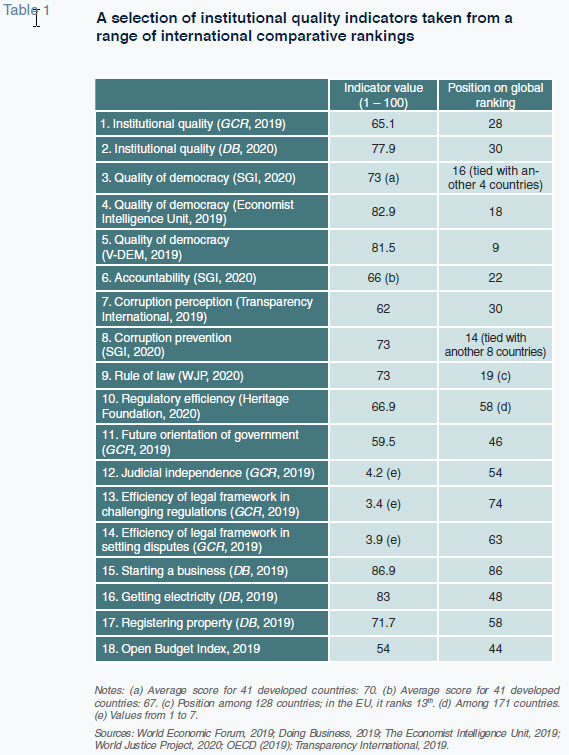

Tables 1 and 2 outline institutional indicator readings for Spain in absolute terms and, more importantly, relative to other countries. The tables yield several interesting takeaways. Firstly, in relation to the more general indicators –those pertaining to ‘institutional quality’– Spain ranks somewhere in the middle; it does not stand out within the overall universe of developed economies but is more of a laggard within the EMU states. Specifically, in the global DB and GCR rankings, Spain placed #30 and #28, respectively, in 2019, which is not too far from its positioning using more conventional economic benchmarks, such as GDP per capita.

With respect to the GCR report, Spain clearly ranks less favourably on institutional quality relative to its overall competitiveness. Specifically, it ranks 23rd with a value difference of 10 percentage points (65.1 vs. 75.3). Those rankings contrast sharply with its position on other dimensions such as physical infrastructure (7th) and health (1st). All of which leaves us with the idea that, in the broadest sense, the institutional framework constitutes a source of weaknesses that undermines, albeit to a limited degree, the Spanish economy’s ability to compete.

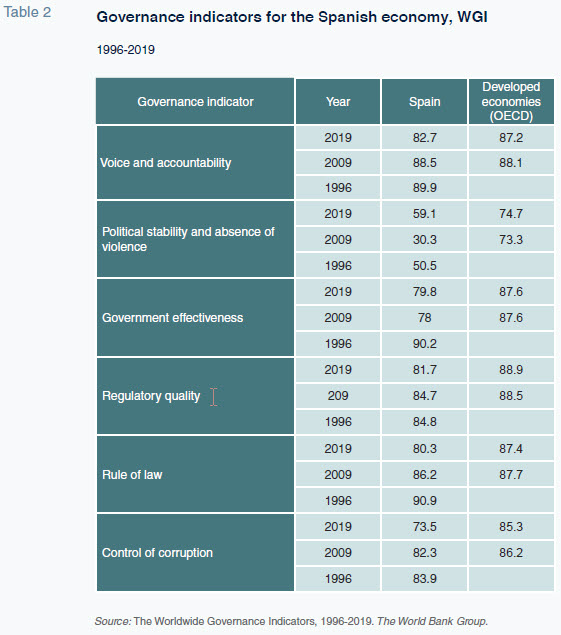

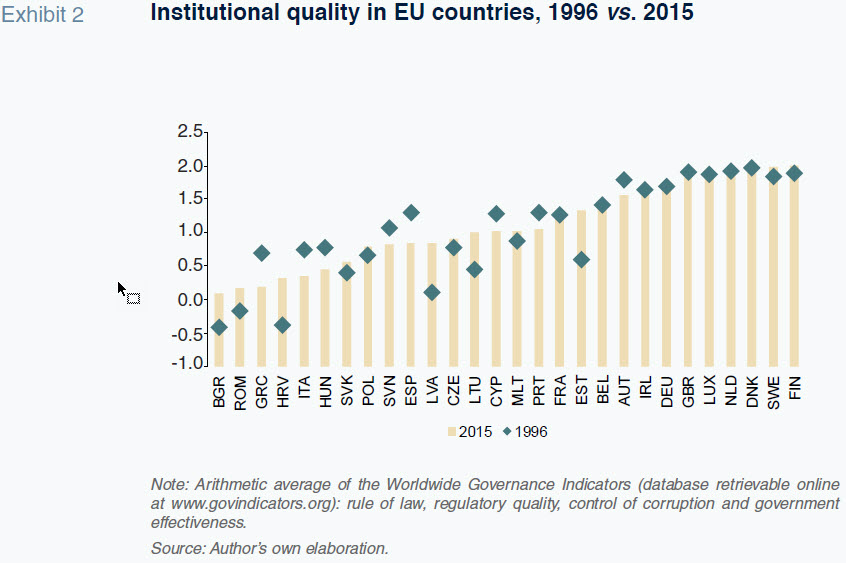

Secondly, the trend in the key institutional indicators over the last 25 years is clearly negative. Table 2 plots Spain’s performance along the six WGI-Governance Matters indicators since 1996. Spain has deteriorated in five out of six indicators. The rest of the reports reveal similar patterns. The deterioration started in the last phase of growth prior to the financial crisis and accelerated during the years immediately following it, a period that was characterised by tough austerity measures. Exhibit 2 shows that Spain is one of the EU countries in which institutional quality has deteriorated most notably over the past two decades. The most plausible explanation for this adverse trend relates the real estate boom and period of sustained growth in abundant and cheap credit during the run up to the financial crisis. During these years, businesses focused their energy on quickly generating profits and the lines between the public and private spheres often became blurred. This created a propitious context for the relaxation of regulatory oversight and a loss of institutional vigour.

Interestingly, Spain’s performance on all international benchmarks turned positive from 2015. For example, in the 2015/16

GCR, Spain ranked 65

th. This involved climbing 35 spots in just three years. Although that trend may have been partly shaped by certain methodological modifications, the turnaround is clearly positive and consistent with the improvement in the overall competitiveness assessment (with Spain gaining 10 positions) and, above all, the improvement observed in TFP in recent years. In short, over the long-term the trend is clearly negative, albeit partially mitigated in recent years.

Thirdly, that idea that Spain’s institutional infrastructure is a drag on its economy–relative to core EU countries– is far more obvious if we delve into certain specific institutional factors. Here we refer particularly to transparency and accountability, the justice system, the regulatory systems, coordination between the national and subnational governments and public sector governance.

In all these matters Spain presents significant institutional deficiencies.

It is important, however, to consider Spain’s integration within the European institutions. Spain’s membership of the EU ushered in dramatic economic transformations, including at the institutional level. The creation of the Economic and Monetary Union reinforced, at least initially, that trend.

Many of the institutional changes –from the law establishing the independence of the Bank of Spain to the creation of an independent fiscal authority, AIReF, in 2013– were driven by European powers. However, alongside this institutional trend another more worrying and largely contradictory development occurred. It was assumed that integration in a common monetary area would bring convergence along a host of macroeconomic and institutional variables. However, that has not happened. Instead, numerous indicators reveal that divergences persisted at least until 2015, and in some cases, have become more acute, particularly by comparison with benchmark countries such as Germany and the Scandinavian countries. This phenomenon not only affects Spain; it affects the EMU as a whole and is one of the main and perhaps less- known problems presented by the unification experiment: widening of differences between those countries that are more institutionally efficient (northern and central Europe) relative to the laggards (eastern and southern Europe) (Bayaert, García-Solanes and López- Gómez, 2019).

One bright spot: Quality of democracy

In recent years, this particular matter has been a heated and controversial topic in Spain. The idea that democracy in Spain is low quality is, in fact, the wrong argument and it is important to point that out because its presence is interfering enormously with the debate over the role of the country’s institutions. It is true that certain aspects of liberal democracy have deteriorated. However, that is a widespread phenomenon –the so-called democratic recession– that is aff much of the world.

All the accredited international reports that assess the performance of liberal democracies place Spain at the forefront at the global level. In the report compiled by the University of Gothenburg (V-Dem), Spain ranks 9th, scoring 0.815 out of 1 compared to Denmark, the leader, with a score of 0.858. According to The Economist Intelligence Unit, Spain continues to fall within the group of ‘full democracies’, placing 18th out of 100 with a score of 8.29, while Norway, the leader, has a score of 9.87. And in the Berstelmann Foundation-SGI report, Spain ranks 16th, tied with four other countries. In the ranking of personal rights compiled by the Social Progress Imperative, Spain placed 15th in 2020 (94.49 out of 100), and on political rights, 19th. Lastly, the Rule of Law Index compiled by the World Justice Project also ranks Spain 19th. All these sources rank Spain among the 20 most robust democracies in the world, suggesting Spain benefits from sound democratic institutions. The fact that Spain features within that elite group of democracies is good news for doing business in Spain.

Transparency issuesTransparency International publishes the benchmark annual ranking of countries’ corruption levels. Looking at its corruption perception index from 2008 and 2018, Spain has fallen from 26

th (61 points out of 100) to 41

st (58 points) among 180 countries, signalling significant problems in this area. The planning scandals that affected over one-tenth of Spain’s town councils and those related with political parties are the main reasons for this adverse trend (to interpret the time series it is important to consider the lag that tends to affect ‘perception’ readings). However, in 2019, the situation improved, with Spain ranking 30

th, with a score of 62 (an improvement is also observed in the SGI- Berstelmann report). However, that change is not enough. Transparency International believes that an economy such as Spain’s should not score fewer than 70 points on the perception index if it wants to maintain a positive image and sufficient level of competitiveness

[2].

Spain’s significant corruption problem is clearly related to shortcomings in government transparency, independent review and accountability. This has had a perverse effect on economic confidence, constituting a long-term barrier to growth. In the 2019 Open Budget Index, Spain ranked 44th , scoring 53 points out of 100, below the OECD average of 68 (International Budget Partnership, 2019). That performance puts Spain in the report’s ‘Limited Available Information’ category.

The recent creation of an independent fiscal authority, AIReF, whose mission is to evaluate the public finances and hold the various authorities accountable, is a positive development. Other potential reforms related with lobbying regulations, limits on parliamentary immunity and the passage of a transparency act, have barely made any progress.

A key problem: The justice system

Based on data published by the World Justice Project, Spain ranks somewhere in the middle in terms of its rule of law performance, placing 19th on the global index and 10th in the EU. The rule of law is guaranteed in Spain and the country does not present a serious or unique problem in this area, with the one exception being an excess of laws. The juxtaposition of laws and regulations at the central and regional levels has created a labyrinth of laws, which citizens and firms find hard to navigate. The Spanish state generates 10 times more legislation than its German equivalent (Sebastián, 2016). Moreover, certain key pieces of legislation are in constant flux, creating an environment of instability and litigation. For example, since 1995, the Penal Code has been amended 30 times and since 2000, the Civil Enforcement Act has undergone over 40 changes (Consejo General de Economistas, 2016). As a result, the number of laws in effect in 2018 was disproportionately high (11,737), having multiplied by four in the last 40 years (Mora- Sanguinetti and Pérez-Valls, 2020). That legislative jungle is a source of incremental transaction costs for all types of contracts.

However, it is the ordinary workings of the justice systems where the most worrying signs of inefficiency are found. The WJP data are satisfactory in relation to personal rights or constraints on government powers (again attesting to the quality of Spain’s democracy) but are less encouraging in regulatory enforcement, civil justice and criminal justice, mainly related to unjustified delays in sentencing or effectively implementing regulations.

The judicial system is a blind spot in the Spanish institutional structure. There is a vast body of literature certifying the economic effects of efficient judicial systems, viewed as fundamental for orderly and credible contract execution. This in turn impacts investment and economic activity via the proper functioning of the credit systems, the creation of new companies, average company size and the existence, or otherwise, of distortions in the home ownership and rental markets (Palumbo et al., 2013).

The European Commission publishes a report comparing member states’ justice systems called The EU Justice Scoreboard (EUJS). The report assesses a number of variables around three dimensions: efficiency, quality, and independence. Spain fares poorly, ranking outside the top 15 on nearly all measures. For example, it ranked 17th on the estimated time needed to resolve civil, commercial and administrative cases between 2012 and 2018 and 23rd on the case resolution rate. It ranks similarly poorly on the quality indicator –the number of judges per 100,000 inhabitants– but has improved on certain specific items, such as the availability of electronic devices and public access to sentences.

The key issue, however, relates to judicial independence. According to the EUJS, the perceived independence of courts and judges among the general public puts Spain at the back of the group (18th in 2020). The GCR report paints a similar picture. In 2019, it ranked Spain 52nd in the world (4.2 points out of 7). This is important as there is evidence of robust correlation between judicial independence and GDP growth.

Regulatory quality and the government efficiency issue

Several studies point to significant differences (7.2 points according to the 2019 DB report) between regulatory quality in Spain and the average for the developed economies. Spain therefore presents substantial shortcomings in this area, which manifest in three key ways. Firstly, excessively complex regulations have noteworthy economic consequences. For example, according to Mora-Sanguinetti and Pérez-Valls (2020), they have a significant impact on business demographics, reducing the number of limited-liability companies (which tend to be larger) and increasing the number of individual business owners, which tend to focus on local markets, subject to local legislation. One of the better documented burdens for the Spanish productive landscape is the weight of micro-enterprises (nearly 95% of the total) and the associated deficit of management capital. Potentially a key reason for the less than satisfactory trend in productivity.

Secondly, Spain’s regional governments have passed between 60% and 80% of the regulations introduced since the Constitution was created. Many of these regulations are often mutually inconsistent and pose a threat to market unity. Reducing competition between the authorities would reduce the regulatory chaos and fragmentation. According to the European Commission, “the restrictiveness and fragmentation of regulation within Spain prevents companies from benefiting from economies of scale” (EC, 2019).

It is important to underline that the issue is coordination rather than decentralisation. The passage of separate and sometimes mutually inconsistent regulations at the various levels of government, aggravated by instability in the decentralisation model and issues with the distribution of fiscal powers, is one of the considerable institutional deficits affecting the Spanish economy (Martínez-Vázquez, Sánchez Martín and Sanz-Arceaga, 2019).

As for its government organisation systems, Spain lags very far behind its peers in the international comparisons. DB includes a series of data regarding the number of steps required and time needed to perform activities that are vital to economic performance, such as setting up a new company, getting electricity or obtaining a building permit. Spain fares very badly on all fronts. With respect to setting up a company, it ranked 86th in the world in 2019, while it ranked 48th for getting electricity and 58th to register a property (Table 1). Also, in 2019, Spain was among the countries furthest behind in selecting, certifying and executing European funds. On the latter measure it ranked fi last, taking 130 days between receiving a final bid and executing a contract.

These indicators illustrate the impact that government efficiency has on transaction costs in key productive sectors. Of particular concern are Spain’s excessive bureaucracy, scant flexibility and diversification, shortfall of skills, and an absence of operating independence. The main consequences are a pronounced trend towards routine work, a lack of initiative and foresight and a shortage of analytical and assessment capabilities.

According to the Quality of Government Institute at Gothenburg University (2015), Spain’s public sector ranked 28th in the world on the professionalism index (4.5 on a scale of 1 to 7) and 33rd on impartiality (0.4 on a scale of -1 and 1.5). The scarce presence of a public professional managerial function has to do with the existence of unclear relationships with the political sphere, which compromise conditions of neutrality (the trait that characterises government systems in countries deemed highly efficient) (Lapuente, 2016).

Institutional shortcomings after the pandemic

The pandemic has made the issues flagged in this paper particularly acute – and their resolution all the more pressing. In 2020, the GCR report, asked about the extent to which the various economies are ready to tackle the challenges ushered in by the pandemic and ensuing recovery effort. Regarding ensuring “public institutions embed strong governance principles and a long-term vision and build trust by serving their citizens, Spain ranked 24th (56.4 points out of 100, compared to the top-ranked Finland, which garnered 78.5 points) (GCR, 2020, Special Edition). This is very mediocre performance which raises important questions about Spain’s present situation and future prospects.

The pandemic has also highlighted the need for specific structural adjustments, such as the so-called digital/green transition. Governments will play a leading role in that transformation effort. The EU has recognised the opportunity, launching its ambitious Next Generation EU recovery packaged. The NGEU funds will require the management of vast public investment programmes with significant power to change important economic dynamics over a relatively short period of time (five years). Spain’s track record suggests a lack of preparation for optimal management of these funds. A manifesto written in 2020 stated: “Our public sector is better prepared to follow guidelines than to manage environments of change and technological disruption that require managing innovation in a manner that is transparent and open to public scrutiny” (López Casasnovas et al., 2020). Thus, the absence of ‘government efficiency’ could undermine Spain’s response to the upcoming changes anticipated in the international economy. To tackle the issue, the Spanish government recently passed legislation (Royal Decree-Law 36/2020) which remains untested, but which undoubtedly marks a step in the right direction.

Conclusion

The idea that our institutions produce very specific economic outcomes is of great interest in interpreting some of the key weaknesses facing the Spanish economy, particularly the disappointing trend in its total factor productivity. By analysing the institutional quality indicators used in several comparative international studies, it is possible to draw certain conclusions.

The first is that Spain’s ranking in all the international institutional quality classifications is, in the broadest terms, mediocre. Although Spain benefits from inclusive political institutions, the flawed institutional structure, which has worsened over the last 25 years, constrains the country’s ability to compete and limits its growth prospects.

Secondly, that negative reading is very pronounced in specific institutional aspects, including low regulatory quality, scant transparency, an inefficient justice system, poor intergovernmental coordination, government efficiency issues and excess bureaucracy. The pandemic and the emergence of disruptive forces of the digital/ green transition have shone a spotlight on those institutional shortcomings.

Those weaknesses are the source of considerable costs and efficiency problems for the Spanish economy. The good news is that there is significant room for productivity gains by improving institutional quality. It is therefore essential that policymakers prioritise the pursuit of far-reaching reforms in these areas.

Notes

Refer to BBVA Foundation-Ivie: Esenciales, 33, 2019.

Note released by Transparency International Spain: “España continúa su mejora en el Índice de Percepción de la Corrupción” [Spain continues to improve its position on the corruption perception index, 2019], January 23rd, 2020.

References

BEYAERT, A., GARCÍA-SOLANES, J. and LOPEZ- GOMEZ, L. (2019).Do institutions of the euro area converge? Economic Systems, 43(3), pp. 1-18.

CONSEJO GENERAL DE ECONOMISTAS (2016). Implicaciones económicas del funcionamiento de la Justicia en España [Economic implications of justice system efficiency in Spain]. Madrid: CGE.

DOING BUSINESS (2019). Doing Business 2016. Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency. Washington: World Bank Group.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2019). Country Report Spain. February. Brussels.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2020). The 2020 EU Justice Scoreboard. Brussels.

INTERNATIONAL BUDGET PARTNERSHIP (2019). Open Budget Survey 2019.

LAPUENTE, V. (2016). La corrupción en España. Un paseo por el lado oscuro de la democracia y el gobierno [Corruption in Spain, A walk on the dark side of democracy and government]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

LÓPEZ-CASASNOVAS, G. et al. (2020). Por un sector público capaz de liderar la recuperación. [Call for a public sector capable of spearheading the recovery], A Manifest.

MARTÍNEZ-VÁZQUEZ, J., TRÁNCHEZ MARTÍN, J. M. and SANZ-ARCEGA, E. (2019). A propósito del Informe de la Comisión de Expertos para la revisión del modelo de financiación autonómica: oportunidades para un sistema más eficiente [Regarding the Expert Committee Report on the review of the regional financing model: opportunities for a more efficient system]. Presupuesto y Gasto Público, 96, pp. 89-106.

MORA-SANGUINETTI, J. S. and PÉREZ-VALLS, R. (2020). How does regulatory complexity affect business demographics? Evidence from Spain. Working Document, 2002. Bank of Spain.

PALUMBO, G., GIUPPONI, G., NUNZIATA, L. and MORA- SANGUINETTI, J. S. (2013). The Economics of Civil Justice. New Cross-Country Data and Empirics. OECD Working Paper, 1060.

QUALITY OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTE (2015-2019). The QOG Expert Survey. Gotemborg.

SEBASTIÁN, C. (2016). España estancada [Spain, stagnated]. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg.

THE ECONOMIST INTELLIGENCE UNIT (2019). World Democracy Report. London.

TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL (2019). Corruption Perception Index.

WORLD BANK GROUP (1996-2019). Governance Matters. Washington D.C.

WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM (2005-2020). The Global Competitiveness Report. Geneva.

WORLD JUSTICE PROJECT (2013-2020). Rule of Law Index. Washington DC.

Xosé Carlos Arias. Vigo University