Decoupling between non-performance and provisions

Surprisingly, Spain saw its banks’ non-performance ratio fall during the crisis alongside a significant provisioning effort. However, if banks are to absorb their pandemic-related losses by the end of 2022, they will need to step up their provisioning by 20-25% compared to 1Q2021 levels.

Abstract: Unexpectedly, Spanish banks’ non-performance ratio fell during the crisis due to the reduction in the absolute volume of non-performing assets and the increase in the volume of gross credit. Despite an 11% contraction in GDP, Spain’s NPL ratio registered an even more pronounced reduction than in other countries. Also noteworthy was the significant provisioning eff made by Spanish banks even after the introduction of more accommodating regulation and accounting rules. However, provisioning started to slow in the first quarter of 2021 and there is a debate as to whether it ought to keep pace with 2020. Non-performing exposures should peak by early 2023, rising by around €40 billion between 2021 and 2022, with consumer credit hit especially hard in relative terms. If the provisioning eff of 1Q21 were maintained for all of 2021, the banks would recognise one-third of the estimated balance outstanding in the wake of the 2020 eff this year. Alternatively, the banks could step up their provisioning by 20-25% so that it is completed by the end of 2022.

Introduction

With the release of banks’ earnings reports for the first quarter of 2021, we now have four sets of quarterly fi statements since the onset of the pandemic. This provides us with enough data to analyse the trend in non- performance and provisions for expected credit losses in the Spanish banking sector. Analysis of these two variables is of particular interest given the degree to which they shaped banks’ earnings performance in 2020 and will probably continue to shape them in the years to come.

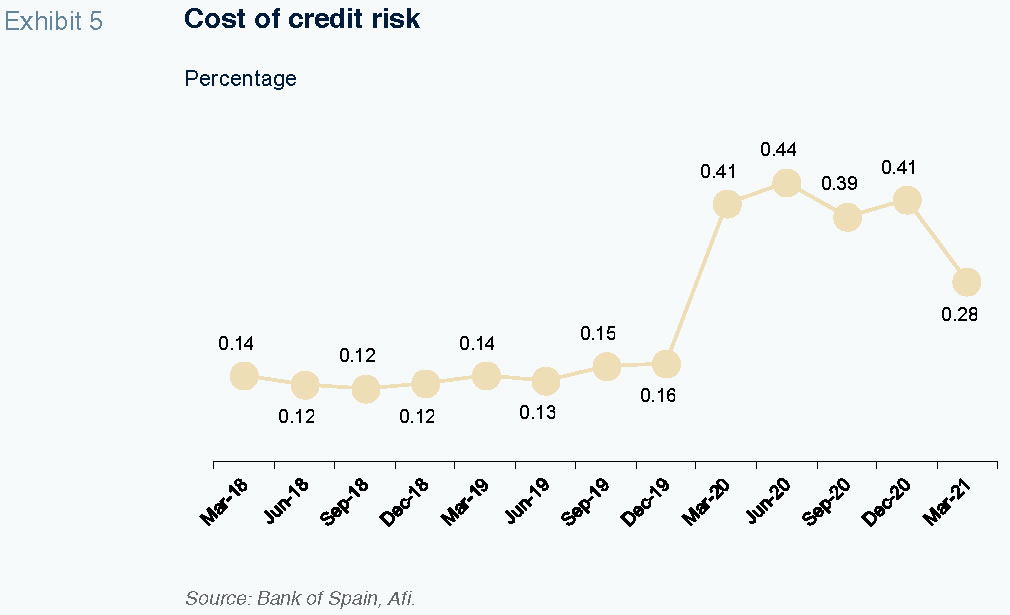

Since the start of the crisis, we are seeing a pronounced mismatch between the trend in non-performance and the cost of risk, the latter measured as the volume of loan-loss provisions over average total assets. More specifically, while non-performance remained stable (even falling a little) during the year of the pandemic, the cost of risk increased sharply in the Spanish banking sector as a whole in 2020.

Declining non-performing loan ratio

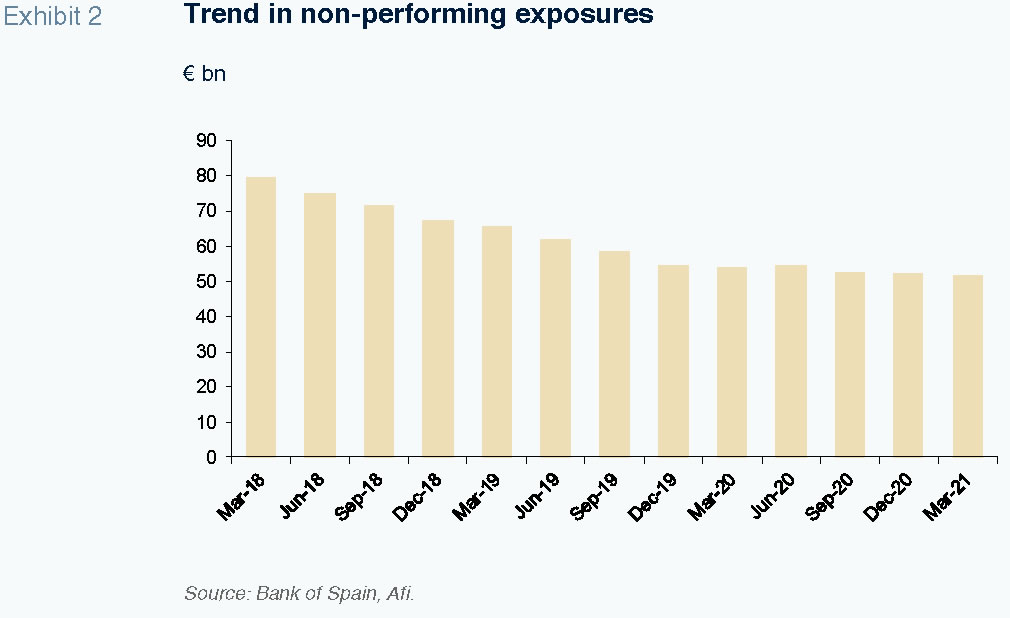

The downtrend in the non-performance ratio has been underpinned by two drivers. The first relates to the reduction in the absolute volume of non-performing assets. That trend, contrary to what one would expect in an economic crisis, has been significantly shaped by the impact of the easing of accounting requirements and the explicit borrower support measures (such as the payment moratoria, the state loan guarantees and the furlough scheme), which have played a crucial role in borrowers’ ability to keep servicing their loans.

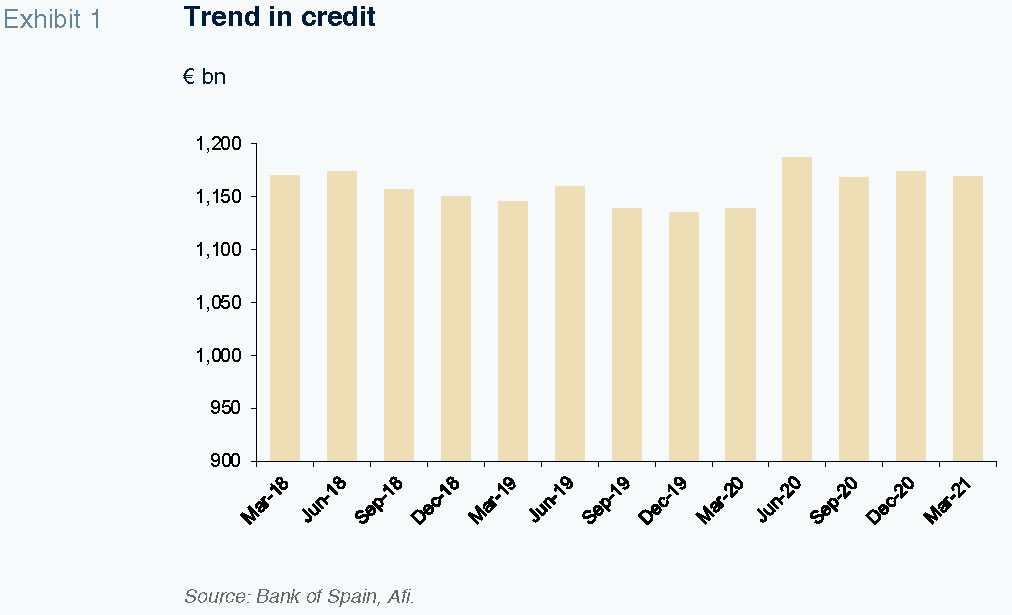

The second driver is the trend in the denominator. The volume of gross credit increased for the first time in a decade in 2020, buoyed by government support measures in the form of public loan guarantees, which was channelled through the offi credit institute, the ICO. As a result, business loans registered growth of 10% in 2020. However, businesses’ initial need for liquidity fell back considerably in the second half of the year and early 2021. Consequently, Spanish banks’ total exposures are now contracting year-on-year.

In short, the stability, and even contraction, in non-performing exposures, coupled with the growth in gross credit, drove a downtrend in the sector’s non-performing loan ratio throughout the COVID-19 crisis.

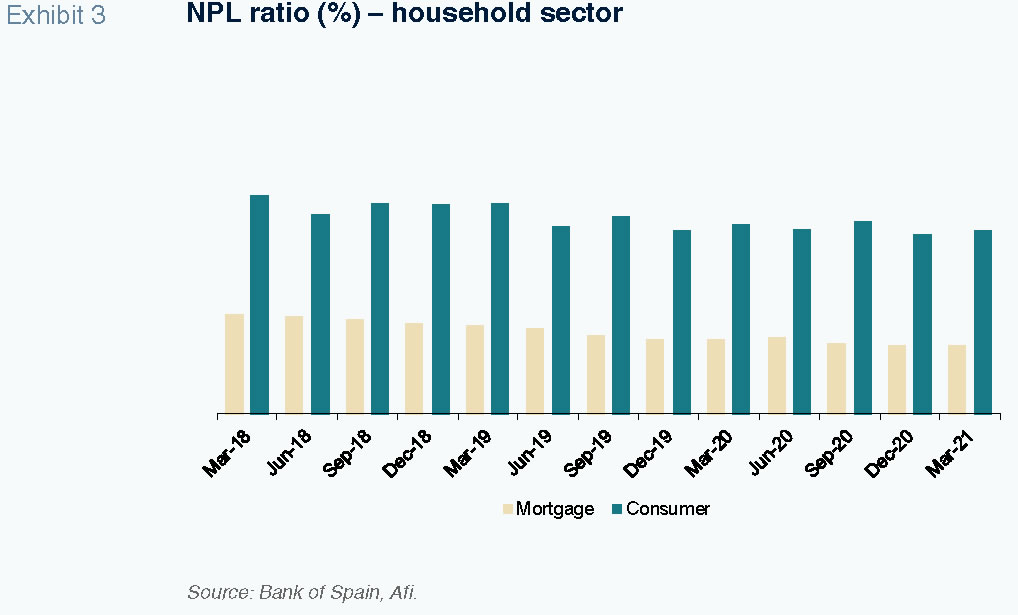

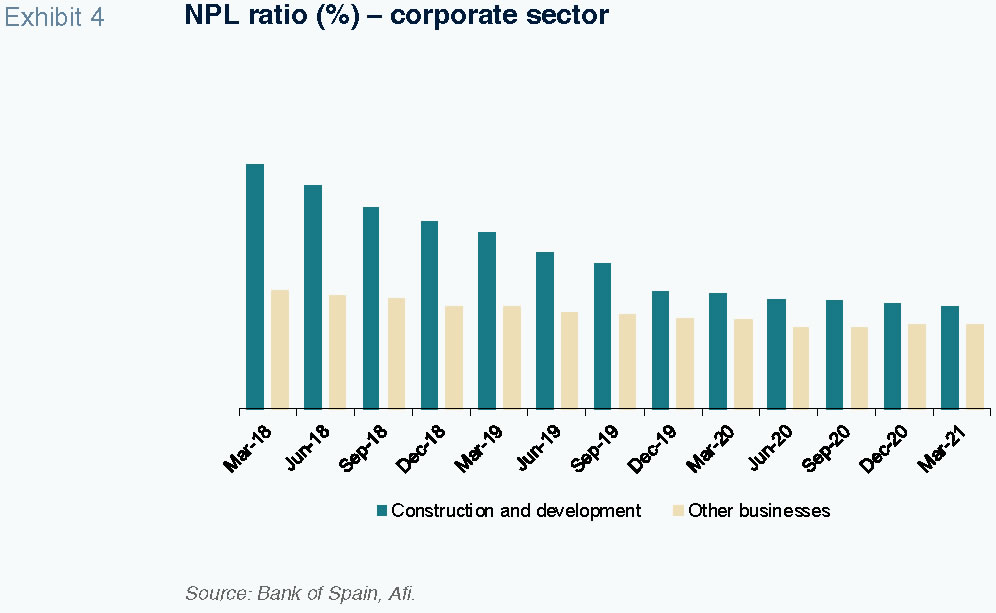

The stability in the NPL ratio across the Spanish banking system was unexpected considering that Spanish GDP collapsed by 11% in 2020. Also surprising is the fact that the NPL ratio registered a more pronounced reduction in Spain than in other countries whose GDP contracted by less, a clear-cut paradox that breaks with all the statistical models that correlate the two variables. Indeed, as shown in Exhibits 3 and 4, the stability (and even decline) in the NPL ratio was observed across all credit segments, rising only slightly in the consumer credit segment in the first quarter of 2021.

Banks’ provisioning efforts

However, the mismatch between non-performance and GDP is not the only paradox that emerged in the banking sector during the pandemic. The other relates to the significant provisioning effort made by Spanish banks, in anticipation of the uptick in non-performance (hence the decoupling). This is unusual given that the regulatory and accounting environments were made laxer specifically to facilitate the deferral of those actions.

As shown in Exhibit 5, the Spanish banking system has been recognising loan-loss provisions at triple the level it had been recording prior to the pandemic. From what we have seen in the first quarter of 2021, the banks have pulled back significantly on the provisioning front by comparison with 2020 but continue to recognise loan losses at nearly twice the average level observed during the two years prior to the pandemic.

The reduction in provisioning by the banks in the first quarter of this year is probably the reason why regulators and supervisors are urging the banks not to ease up on their front- loading of provisions – with non-performance still expected to rise. Their concern is that the relaxation of provisioning may drive growth in profits that could be used to justify new dividend payments, which were restricted in 2020.

Projected trends in asset impairment and banks’ loss absorbing capacity

In the midst of the debate about whether the levels of provisions in 2021 should maintain the pace set in 2020, we believe it is timely to share our outlook for the possible trend in asset impairment and the banks’ ability to absorb the losses.

To do that, we have prepared credit impairment projections based on econometric models, introducing adjustments in order to capture a number of different extraordinary aspects that will unquestionably have an impact on banks’ fate in the coming months. More specifically, our estimates contemplate the following drivers:

- The economic recovery and expected macroeconomic scenario;

- The volume of savings built up during the crisis, which, judging by the recent trend in bank deposits, is already being released as restrictions are relaxed;

- The impact of the extraordinary measures implemented to mitigate the effects of the crisis, such as the furlough scheme, maturity extensions and grace periods for secured transactions, and the recapitalisation of certain entities; and,

- The advent of the NGEU funds.

Based on those drivers, we expect non- performing exposures to peak towards the end of 2022 or in early 2023, rising by around €40 billion between 2021 and 2022. Non- performing exposures will then improve, with non-performance close to but still just above pre-COVID levels in 2024.

Looking at specific segments, we expect consumer lending will be the hardest hit on a relative basis. Mortgage credit will fare the best by our estimates, sustaining a slight uptick when the furlough scheme is rolled back.

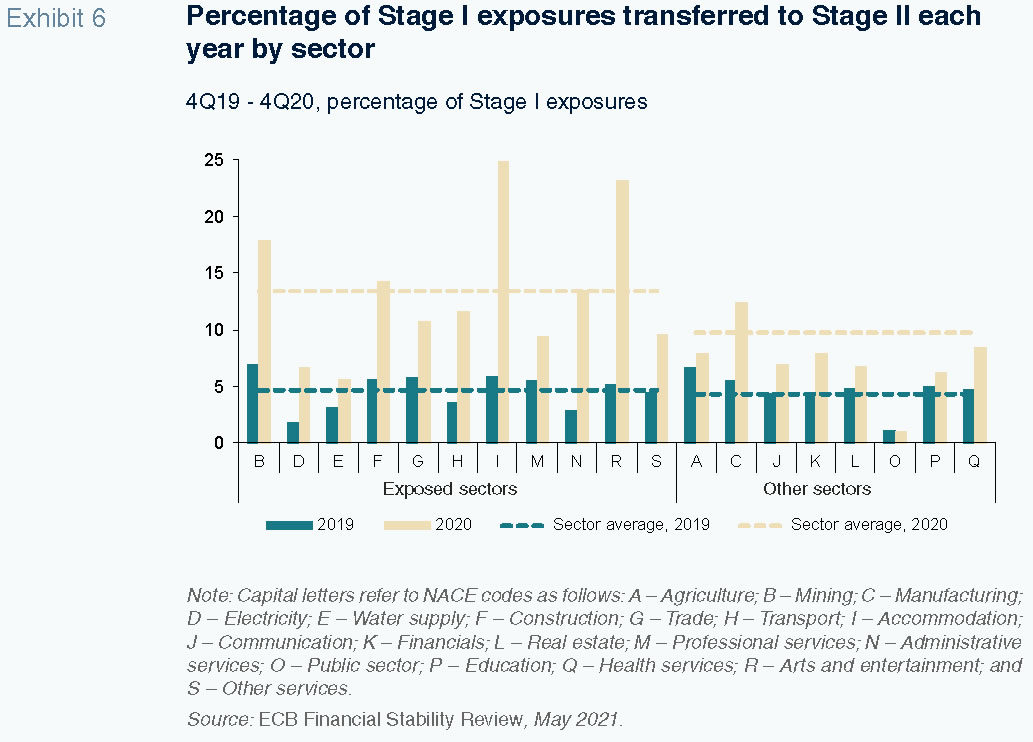

In absolute terms, the business loan segment will take the biggest blow, albeit shaped by considerable differences by sector and region. We are forecasting a significant increase in non-performance in the sectors more exposed to the pandemic (accommodation, arts and entertainment, transport, etc.), with only small increases, or even declines, in non- performance in the less-exposed sectors (primary sector, etc.). That uneven sector outlook was touched upon in the analysis performed by the European Central Bank in its most recent Financial Stability Review. As shown in the following exhibit, the significant increase in transfers from Stage I to Stage II exposures in 2020 (note that Stage III exposures remained flat or even declined) was more intense in the sectors most sensitive to the pandemic, a possible prelude to an increase in non-performance in those sectors.

Given the projected increase in impairment attributable to the effects of the pandemic (of around €40 billion), and assuming average NPL coverage of 60%, the banks would have to recognise around €24 billion of impairment allowances over a three-year time horizon (including 2020). The significant effort made by Spanish banks to front-load their loan- loss provisions in 2020 means they have already recognised roughly half (47%) of the allowances corresponding to the estimated uptick in non-performance. As a result, and based on our estimates for non-performance, Spanish banks would still have to recognise a little over €12 billion of loan impairment allowances against their earnings in 2021 and 2022.

To test the fit between these forecasts and the actions taken by the banks in early 2021, we analysed the first-quarter earnings data for the Spanish banking sector published by the Bank of Spain. Based on those figures, the provisions recognised during the first quarter of this year mark a significant slowdown year-on-year but remain higher than those recorded in 2019. More specifically, the volume of provisions recognised in 1Q21 is practically twice the average recognised in 2018 and 2019 but around 13 basis points below the cost of risk reported in 2020.

If the provisioning effort of 1Q21 were to be maintained for all of 2021, the banks would recognise one-third of the estimated balance outstanding in the wake of the 2020 effort this year. As a result, the adverse effects of the pandemic will be over by the end of 2023, a timeframe that the supervisor will possibly consider overly lax.

If, alternatively, it is deemed desirable to bring the full provisioning eff forward so that it is complete by the end of 2022, the banks would have to step up their provisioning somewhat in 2021 (by a further 20%-25%) compared to that observed during the first quarter.

In terms of the impact on overall system profitability (ROE), we estimate that the difference between spreading out the impact over two versus three years is equivalent to around one percentage point of ROE in 2021. At any rate, the banks’ earnings are set to increase very considerably this year compared to 2020, when the system as a whole registered a return of around 1.5%, before factoring in the impairment of goodwill outside of Spain, which put that metric into negative territory.

References

BANK OF SPAIN (2021). Quarterly report on the Spanish economy. June.

ECB (2021). Euro area lending survey. January.

ECB (2021). Financial Stability Review. May.

Marta Alberni, María Rodríguez and Federica Troiano. Analistas Financieros Internacionales – A.F.I