Spain’s youth: Precarious employment and unaffordable housing

The fragility of the Spanish job market, characterised by a high incidence of temporary contracts and high structural unemployment, particularly impacting the Spanish youth, has led to an increased concentration of young people in major urban areas due to migration in search of work opportunities. However, less affordable housing in the cities is not only reducing the wealth of this age cohort but is accompanied by negative repercussions for society as a whole, which need to be addressed by public policies aimed to foster quality job creation, as well as affordable housing.

Abstract: In just over 15 years, Spanish youths have suffered the fallout from two economic crises that have hurt their current wellbeing as well as their expectations for the future. The fragility of the Spanish job market, characterised by a high incidence of temporary contracts and high structural unemployment, has taken a particularly heavy toll on the country’s young people for whom job quality and employment rates have been significantly lower. This has led to an increased concentration of young people in major urban areas, migrating in search of work opportunities. However, in those cities young people are facing more expensive housing, undermining their savings and making it hard to buy a home, ultimately reducing their wealth. This problem has important repercussions for society as a whole related to increased pressure on the social security system due to lower birth rates, in addition to increases in income inequality and decreased aggregate demand with knock-on effects on the real economy. To revert this situation, it is vital to pursue evidence-based public policies that foster the creation of quality work, job stability and housing affordability, especially in the large cities where demand for housing for young people is concentrated. Such policies will be crucial to ensure Spain’s youth can fully realise their full potential and contribute to the country’s economic growth and collective wellbeing.

Situation facing housing seekers

The millennials, the common term for the generation born in the last two decades of the twentieth century, face a very different situation than their parents when it comes to climbing the housing ladder. This cohort, affected particularly harshly by the recent crises, are in a worse financial position on average than the generations that preceded them, while facing an increasingly tight property market shaped by growing competition on the demand side coupled with rigid housing supply.

This situation has frustrated a generation of youths who have not seen their academic efforts pay off. Indeed, the millennials are the best-educated generation in history: 53% of youths aged between 25 and 34 have completed higher education, up 14pp from 20 years ago. Indeed, the early school leavers rate among people aged between 18 and 24 has been declining gradually for the past decade, closing the gap with the European average (according to Eurostat, in 2013, that gap stood at 11.8pp but by 2022 had closed to 4.3pp).

Yet, after completing their studies, Spanish youths have found it hard to find work, as evidenced by a youth unemployment rate of 28%, which is twice the EU average (14%). This situation, which affected as many as 55% of youths during the Great Recession, has consequences in wage and labour terms that last beyond the period of unemployment, as evidenced by numerous studies that have attempted to quantify the scars unemployment can have on young people’s professional careers (Gálvez-Iniesta, 2023).

Moreover, when they manage to find work, young Spaniards tend to hold less stable jobs (the incidence of temporary work among people under the age of 30 in 4Q23 was 35%, 19pp above the national average) for which they are often overqualified (37% were overqualified in 2022, making Spain the second EU country where this issue is most prevalent).

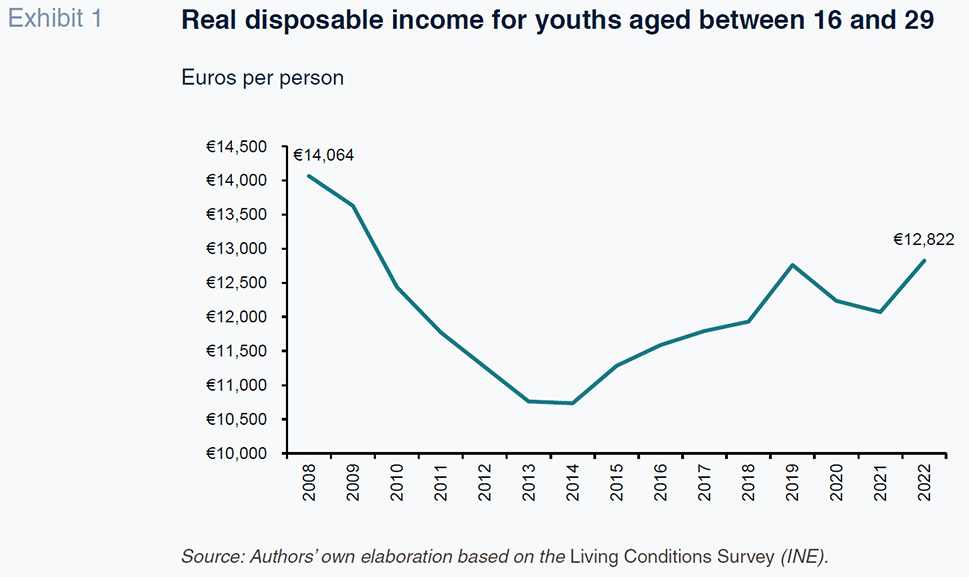

In addition, Spanish youths have seen their financial situation deteriorate considerably in recent decades: in 2022, the real disposable income of those under the age of 29 was similar to that observed in 2010, highlighting a truly lost decade in terms of pay gains for young Spaniards.

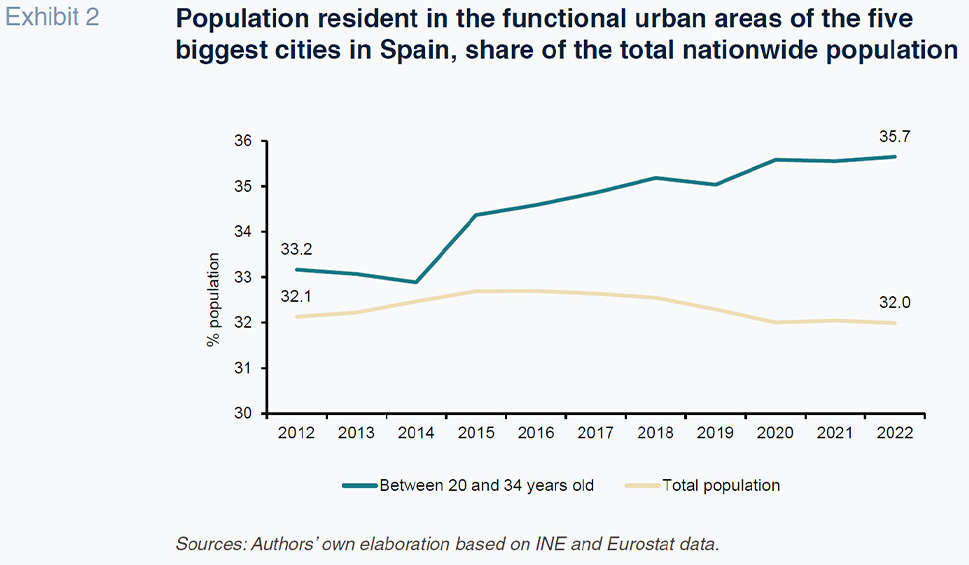

Faced with this panorama, growing numbers of young people are deciding to move to the big cities in search of job opportunities better aligned with their training and expectations. During the past decade, the percentage of young people living in major urban areas has increased substantially. Specifically, in 2022, over one-third (35.7%) of young Spaniards aged between 20 and 34 were living in functional areas of Spain’s five most populated cities,

[1] growth of 2.5pp from 2012.

However, what initially appears to be a solution to these young people’s labour woes also implies a higher cost of living which may be undermining their already low savings rates. According to the cost of living index for Spanish cities compiled by the Bank of Spain (Campos

et al., 2021), in 2020, the cost of living in the two biggest cities (Madrid and Barcelona) was nearly 20% higher than the average across the rest of Spain’s urban areas. That article concludes that considering the fact that average private sector salaries in those cities are 45% higher, the wage gains adjusted for these cities’ cost of living declines to 21%.

However, the wage dividend derived from living in these cities depends largely on which part of the wage distribution these people find themselves in and, as we have seen, young people are on the bottom rung. That means that the higher cost of living of moving to these cities may not be offset by higher earnings during the first few years working there.

Situation in the property market

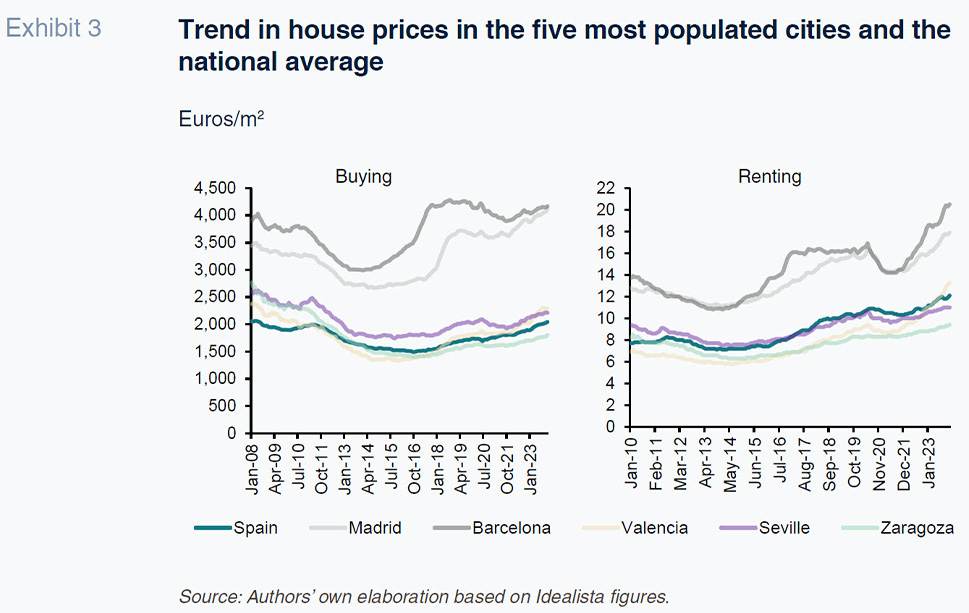

The bulk of the higher cost of living in a big city stems from tight property markets. Rental and owned house prices have been rising sharply in these cities, particularly in the two largest cities (Madrid and Barcelona), which are home to 27.1% of young Spaniards. Rent (euros/m2) in Madrid and Barcelona is currently 8.9% and 24.6% more expensive, respectively, in real terms than in 2010, whereas young people’s real earnings have not increased in that interim. The growing difficulties in accessing the housing market are tangible in the two largest Spanish cities.

If they want to buy a house, young people have a very hard time saving the money needed to make the down payment. Moreover, since 2021, the financial burden has increased, with interest rates jumping from close to negative territory to an annual average rate of 3.6% in 2023. That is particularly relevant for young people looking to buy as their insufficient savings levels leave them largely reliant on mortgages.

Elsewhere, young Spaniards face intense competition in this market and the profile of the buyers is playing an important role in the rise in prices. In the third quarter of 2023, 9.2%

[2] of the housing transactions completed in Spain involved non-resident foreign buyers, who tend to purchase houses at higher average prices, underpinned by greater financial wherewithal compared to the Spanish average. In tourist-heavy provinces such as Alicante, Malaga, and the Balearics, that percentage fluctuates at around 30% of all transactions. Young people not only face competition in the property market from foreign buyers, they also have to compete with resident citizens who already own a home, who currently account for roughly half of all transactions.

Housing affordability for Spanish youth

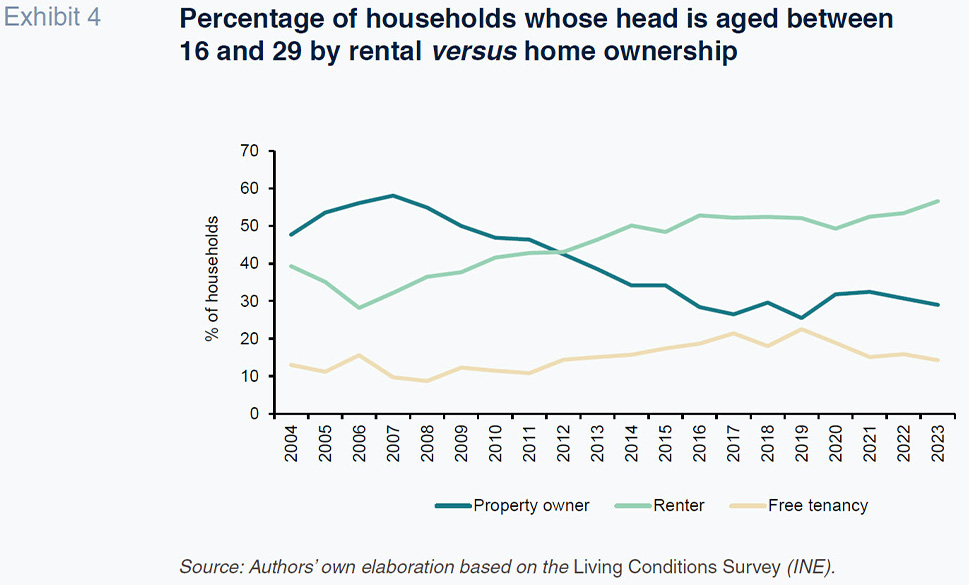

Despite the increase in rents, the impossibility of saving enough money to make a down payment on a house leaves the majority of young people inclined to rent (specifically, 56.6% of households made up of people aged between 16 and 29 in 2023 according to the INE). Although this trend may also have been influenced by shifts in preferences around living arrangements, since the beginning of this century, the percentage of households in home ownership in the 16-29 age bracket has fallen by over 18pp (from 47.7% in 2004 to 29% in 2023).

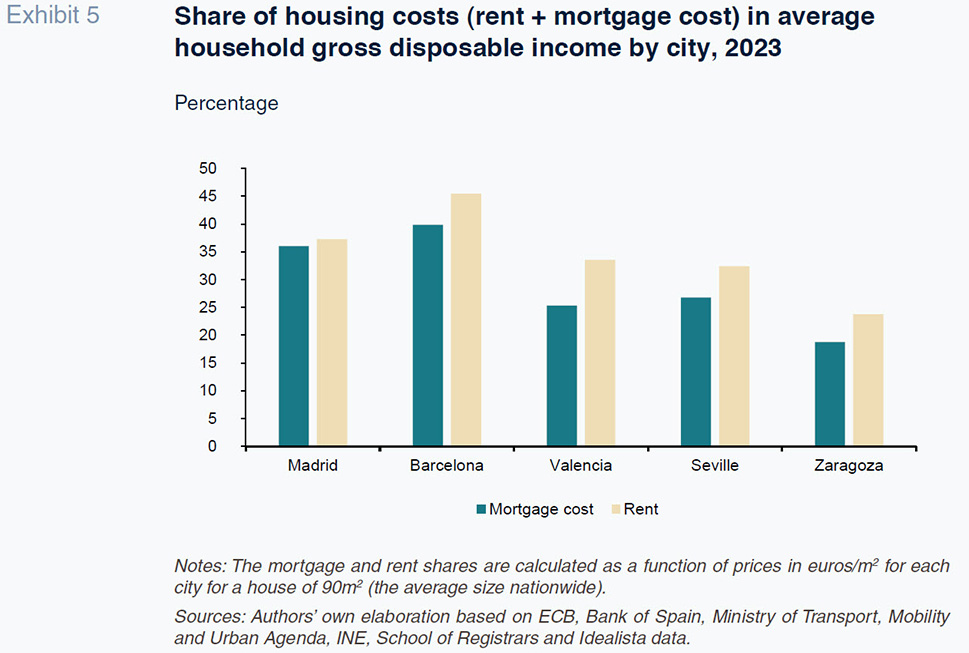

However, the financial burden implied by rent payments relative to average household income, while varying from one city to the next, is higher than the burden implied by mortgage servicing in the five cities analysed. The financial convention is that it is not financially sound to earmark more than one-third of income to housing costs. However, a household with average income levels in Madrid or Barcelona has to devote more than that threshold whether it buys or rents.

Moreover, in the case of young people, whose income levels are lower, these burden ratios are even higher. On average nationwide, the burden of rent costs for a person aged between 16 and 29 with average income starts to exceed the recommended threshold from 30m

2, with a 45m

2 apartment taking up half of their disposable income.

Against that backdrop, many young people are unable to afford rent and are being forced to constantly push back the age at which they leave home, which passed the age of 30 in 2022. Despite starting stable work from the age of 23 and a half, young Spaniards leave home nearly four years later than the European average, a period that has only lengthened in the last decade: +1.6 years compared to 2012. This delay, coupled with population ageing, has led to a drastic drop in the percentage of Spanish households whose head is under the age of 35: from 14.7% in 2002 to 6.7% in 2020, according to the Bank of Spain.

One last consequence of being unable to afford to buy a home is the erosion of wealth in this age bracket. Specifically, the median real net wealth of young households in 2020 (24,000 euros) barely accounted for a third of that of their peers in 2002 (87,200 euros), according to the Bank of Spain, with significant implications for intergenerational inequality.

Conclusions

In short, Spain’s young generations face a serious housing affordability issue. Young Spaniards, despite being better educated than any generation that went before them, face real difficulties in getting onto the home ownership ladder or renting a house due to wage stagnation, growing competition from international buyers, limited supply and rising prices.

This problem is not restricted to this age group but has important repercussions for society as a whole. The fact that young Spaniards are leaving home later and later delays the age at which women have their first child and weighs on the birth rate, one of the reasons why Spain presents the second-lowest birth rate in Europe. That low birth rate will end up affecting intergenerational cohesion, the pillar underpinning numerous public policies, notably including the social security system.

In turn, the youngest generations, who earn less, are earmarking a growing share of their income to paying rent, increasing inequality insofar as their money flows from more vulnerable groups to better-off groups (property owners). The fact that a growing share of income goes to housing costs is also not good news for aggregate demand, hurting savings and the consumption of other goods and services with bigger knock-on effects on the real economy.

The way these problems play out will depend largely on what happens in the housing and job markets in the years to come. Although the authorities are backing measures in an attempt to curb price growth and so alleviate the housing cost burden for certain groups, the effectiveness of these policies is unclear, and their results still need to be assessed.

To revert this situation, it is vital to pursue evidence-based public policies that foster the creation of quality work, job stability and housing affordability, especially in the large cities where demand for housing for young people is concentrated. Only by so doing can Spain guarantee that its youths can fully realise their human and social potential and contribute to the country’s economic growth and collective wellbeing.

Notes

As of 1 January 2023, those cities were: Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, and Zaragoza.

Source: Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda.

According to Idealista, the average price of home purchases financed by mortgages arranged by foreigners in 2023 was 326,227 euros, compared to a national average of 258,575 euros.

References

FORTE-CAMPOS, V., MORAL BENITO, E. and QUINTANA, J. (2021). A cost of living index for Spanish cities.

Bank of Spain Economic Bulletin, 3/2021.

GÁLVEZ-INIESTA, I. (2023). Ser Joven en España y las cicatrices de las recesiones. [Being young in Spain and the scars from the recessions. Nothing is free in life.]

Nada es Gratis.

https://nadaesgratis.es/admin/ser-joven-en-espana-y-las-cicatrices-de-las-recesiones IDEALISTA. 19 February 2024.

Los extranjeros que piden hipotecas en España ganan 6,000 euros y buscan casas un 20% más caras [Foreigners who apply for mortgages in Spain earn 6,000 euros and look for houses that are 20% more expensive].

Retrieved from the following link

Marina Asensio and Javier Serrano. Afi