The housing market: An uneven recovery across regions

Over the past years, Spain’s housing market has, to varying degrees across regions, rebounded in terms of prices and transaction volumes, while improving in affordability. Although the housing market is expected to cool in the near-term, it is unlikely to experience a hard landing.

Abstract: House prices in Spain have recovered significantly over the past years and currently stand at a little over 80% of pre-crisis peak levels. Nevertheless, noteworthy variation exists across Spain’s regions. While nine provinces have outperformed the national average, 22 of Spain’s provinces have achieved a price recovery equivalent to just 65% of peak levels. Furthermore, the rebound in transaction volumes has lagged the recovery in prices. Volumes currently stand at just over 60% of peak levels but present considerable differences across provinces. It is worth highlighting the weak new housing construction figures. These statistics suggest Spain’s housing market is still digesting the legacy stock of unsold housing from the previous construction boom. Lastly, housing affordability has improved in all regions, even those in which the price recovery has been most dynamic, putting prices at close to pre-crisis levels. Looking forward, the data suggest the housing market is likely to experience a soft landing rather than another crash. That said, the varying degrees of recovery draw attention to important structural dynamics, which could pose future challenges.

Introduction

Interest from diverse stakeholders in the housing situation is longstanding. This interest has materialised as a debate that can be approached from many angles, especially in Spain where the last major financial crisis was closely related with the bursting of the real estate bubble. Supply and demand variables evidence the fact that the housing market has staged a strong recovery in recent years. While, the most recent indicators point to a slowdown, the lack of major imbalances suggests this is unlikely to lead to another market collapse (Ocaña and Torres, 2019). The housing market is also closely related with financial variables, which have been a source of positive news for the housing sector (Carbó, Cuadros and Rodríguez, 2019).

The aforementioned slowdown had begun to take shape at the end of 2019, with the contraction in supply, reflected in indicators such as new construction visas and cement consumption, as well as in demand, as perceived in transactions (the first year exhibiting negative growth after four years of positive growth rates above 10%) and mortgages. However, it should be noted that as regards both demand side indicators, previously, in the months of August and September, they presented a strong contraction due to the entry into force of the new Mortgage Law. At present, there is not enough subsequent data to analyze how much these indicators have recovered, but it seems that it is not enough to compensate for the slowdown due to the general cooling of the market. This panorama has dragged the indicator of confidence in construction to low levels, but it remains much higher than those levels registered a couple of years ago. Meanwhile, according to the latest available data (through the third quarter of 2019) on average housing appraisal values, there has been a similar increase as in the previous year, with rates above 3%.

This paper analyses the housing market from a regional and local perspective that takes into consideration patterns of marked segmentation by multiple variables, such as the size, type or location of housing. The housing sector is commonly referred to as a niche market. This description reflects the fact that a country’s housing supply does not necessarily meet the specific demands of all consumers. Individuals require housing with specific features and in particular locations. As a result, if preferred housing options are in short supply, they will command high prices, and vice versa. Thus, while top-down analysis does reveal key insights and trends, it is worth drilling down more locally. In short, we will examine a series of variables in order to depict the recovery of the real estate market across the various regions of Spain.

Recovery in prices and transaction volumes

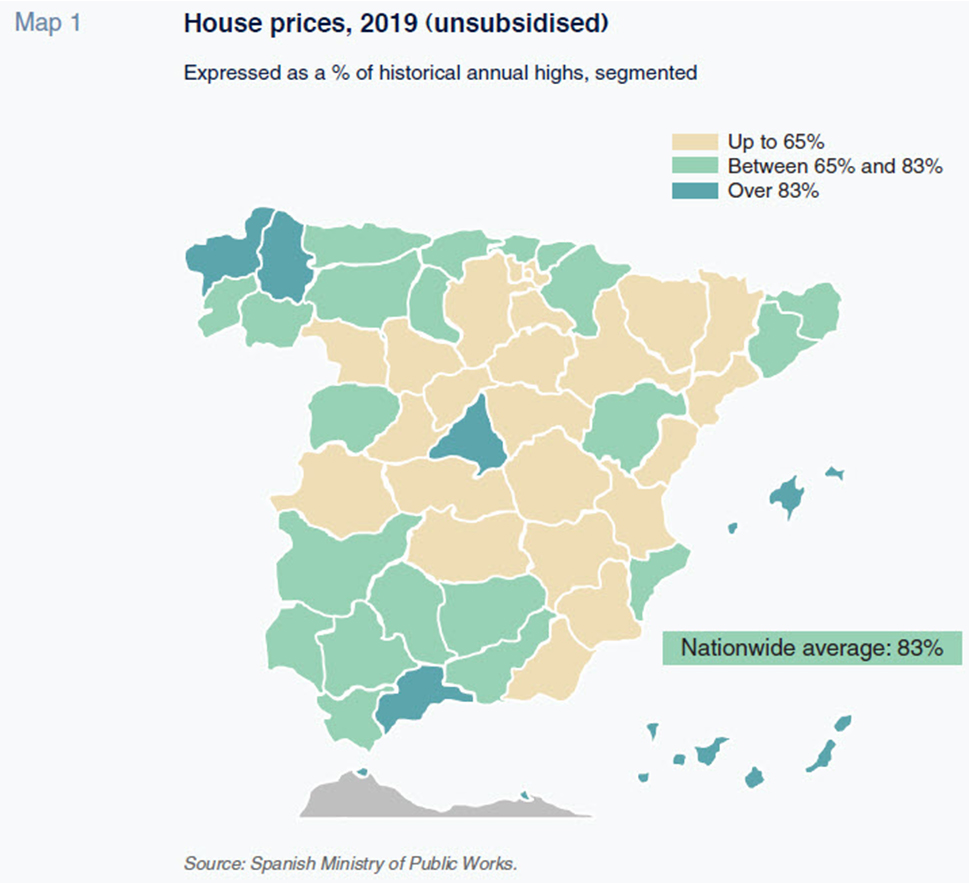

As of the third quarter in 2019, the Spanish housing market’s value stood at 83% of its peak size pre-crisis. Nine of Spain’s provinces and autonomous cities saw price recoveries above the national average, whereas in 43 territories the prices recovery has lagged the national average (Map 1).

The recovery has been particularly strong in the Balearic Islands, where prices have already reached 2008 peak levels. As well, in Malaga (province) prices have risen to 90% of peak levels. The autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, Community of Madrid, Lugo and Santa Cruz de Tenerife also present strong price recoveries of around 86%. They are followed by Las Palmas and La Coruña.

The 43 territories in which price recovery has lagged the national average include the province of Barcelona. Here, prices are equivalent to 75% of peak levels. In 22 provinces, house prices remain below 65% of the peak prices reached before the crisis. The worst-performing provinces are Toledo, Cuenca and Guadalajara in Castile-La Mancha, Castellon in Valencia, Tarragona and Lerida in Catalonia and Burgos and Avila in Castile and Leon.

All of the capitals [1] in the provinces where price recovery has been stronger than the national average have recorded higher growth than the average in their regions. In contrast, provincial capitals where price momentum has been weaker have sustained gains that similarly lag their regional average. This suggests that potential buyers have lost interest in the capitals of these provinces, with other cities and towns becoming more attractive for different reasons, such as proximity to another dynamic region. This has turned them into commuter or dormitory towns, e.g., towns in the province of Guadalajara with respect to Madrid.

As for the number of transactions (unsubsidised housing market), this metric topped 800,000 a year –even rising above 900,000 in 2006– in the years before the bubble burst, which implied a pace of 1.9-2 house sales for every 100 inhabitants. The volume began to trend lower from 2009, falling until 2016 when it stood below 1 sale per 100 inhabitants. In recent years, house sales have recovered gradually, topping one transaction per 100 inhabitants. That said, transactions did lose steam in 2018, mainly due to strong price growth (Registradores de España, 2019a).

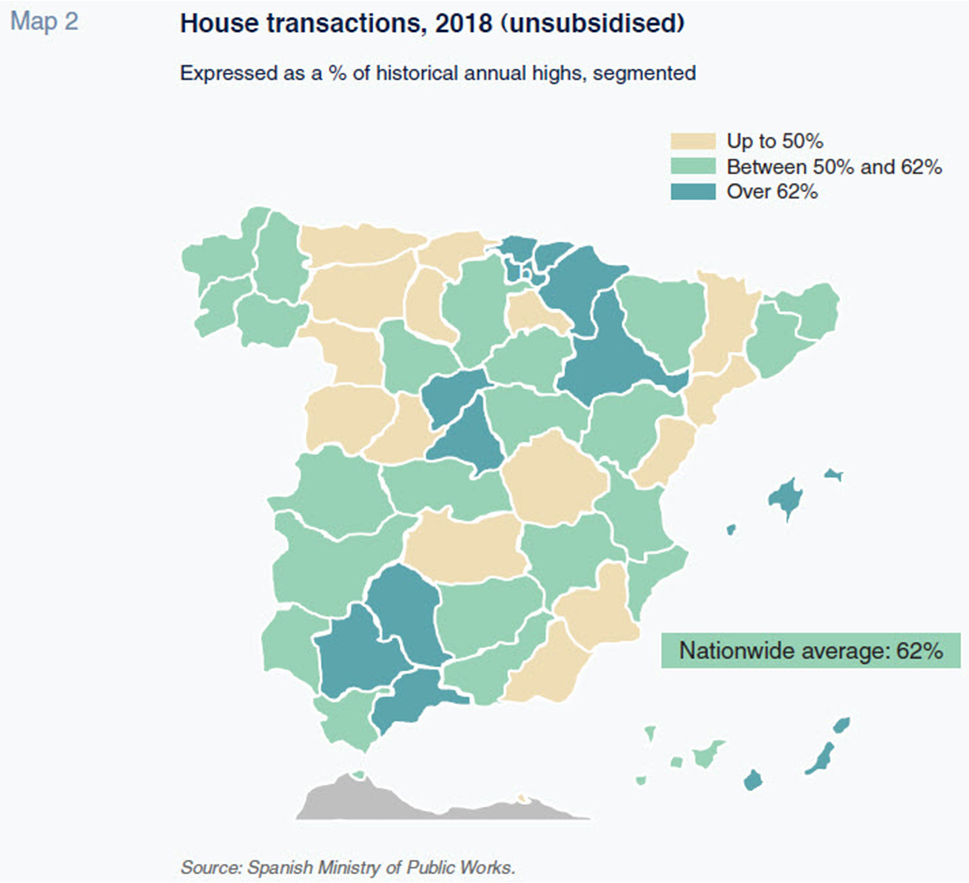

While transaction volumes have strengthened, the recovery has been more tepid than the rebound in prices, with volumes remaining far below pre-crisis levels. In Spain, transaction volumes have recovered to 62% of the peak reached in 2006. As shown in Map 2, volume recovery has been above the national average in 12 provinces. In 16 regions, however, transactions remain at less than 50% of the pre-crisis peak. The remainder fall somewhere in between.

The provinces in which transactions have recovered the most are also those in which prices have recovered strongly. Exceptions include La Coruña and Lugo in Galicia where the healthy price recovery has not been accompanied by a marked improvement in volumes. At the other end of the spectrum, Navarre, Alava and Vizcaya have all sustained strong volume recovery in the absence of significant price gains.

Second-hand houses have dominated sales in recent years. Between 2014 and 2018, just one in every ten transactions involved a new build, compared to four of every ten in the run-up to the crisis. Those figures evidence the stock accumulated in the period before the collapse, which was so large that it had to be absorbed gradually over the following years. Nevertheless, the stock of unsold housing in Spain remains at over 400,000 homes (Alves and Urtasun, 2019).

Consequently, the recovery in the number of finished homes has been modest. Whereas between 2004 and 2008, Spain constructed more than half a million new homes a year, at present that number stands at just over 50,000. By region, leaving the exceptional case of Melilla aside, the recovery has been strongest in the Basque provinces of Guipuzcoa and Vizcaya, which in 2018 recorded new builds equivalent to 35% of the pre-crisis peak. In the rest of the Spanish provinces, that figure stands at under 30% and in 34 it remains at less than 10%.

Population and employment are key price drivers

The Spanish population was growing at an annual average rate of close to 2% before the onset of the crisis in 2008. That growth subsequently dipped sharply, even entering negative territory between 2013 and 2015. The population began to rise once again in 2016, with growth reaching 0.7% in 2019. This trend occurred across Spain’s provinces and the rate of population growth has not recovered to pre-crisis levels in any of them. Nevertheless, there are 19 provinces whose populations have reached series highs, topping their pre-crisis peaks in absolute terms.

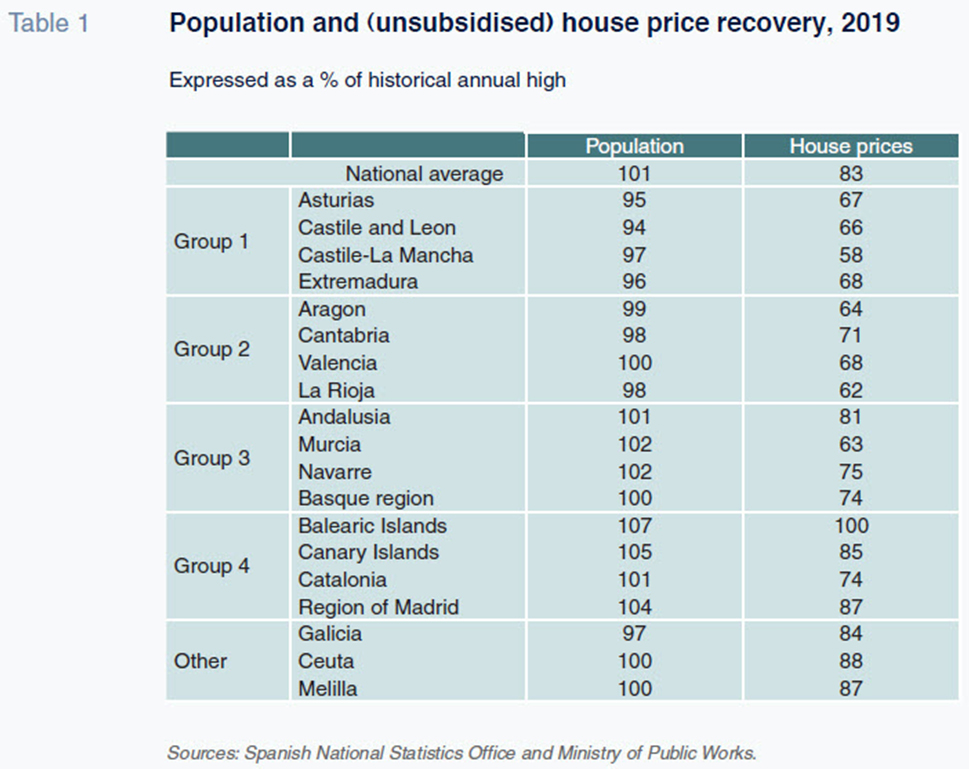

Population growth is very closely correlated with housing prices. We can group Spain’s regions into four categories as a function of the trend in the two variables (Table 1):

- The first group consists of those regions where population loss has been substantial and price recovery is trailing the national average. Examples of this dynamic include Castile and Leon, a region where all of the provinces have seen a decline in their populations and prices have recovered to just 66% of peak levels. Castile-La Mancha has also seen its population shrink in all of its provinces other than Guadalajara, while price recovery stands at around 58% of pre-crisis levels. In Extremadura and Asturias the population has decreased and price recovery stands at 68% and 67% of pre-crisis highs, respectively.

- The second group is made up of provinces registering similar price growth to the first group but smaller population losses. This group comprises Aragon, Cantabria and La Rioja, where prices stand at 64%, 71% and 62% of peak levels, respectively. They are joined by the region of Valencia, where all provinces other than Alicante have lost residents and prices have recovered to 68% of peak levels.

- The third group includes the regions which have sustained net positive population growth combined with moderate house price recovery. It encompasses the regions of Murcia and Navarra, where price recovery stands at 63% and 75% of pre-crisis levels, respectively. It is accompanied by the Basque region at 74%, although the province of Vizcaya has seen its population decline. Andalusia also falls into this category. Prices in this region are at 81% of peak levels, which is higher than the other regions in this category on account of the sharp price recovery observed in the province of Malaga (95%).

- The fourth category is composed of the regions where population growth has been more pronounced and price recovery has also been intense. The Canary Islands and Balearic Islands are particularly noteworthy. Both have sustained very significant population growth and price recovery with respect to peak levels of 85% and 100%, respectively. The Madrid region also stands out with price recovery of 87%. This group is joined by Catalonia, although population growth has been lower due to a decline in Lerida.

Spain’s autonomous cities, on account of their special characteristics, tend to exhibit different trends that make it hard to group them together with the regions. These cities have seen virtually no population growth but prices have recovered strongly, above the national average.

Galicia does not fit into any of the categories. Although it is losing residents, especially in Lugo and Orense, price recovery has been strong at 84% of peak levels. If we look at the net change in population in the universe of towns with more than 50,000 inhabitants, the loss is not particularly significant, which partially explains the anomalous dynamic and mismatch with respect to the four groups. Specifically, the population loss has been concentrated in small towns of much lower significance in the housing market.

Looking at Spain’s other regions, if we analyse the population trend in the larger towns only –those with over 50,000 inhabitants– the snapshot is similar to that revealed by the trend in each region’s population as a whole.

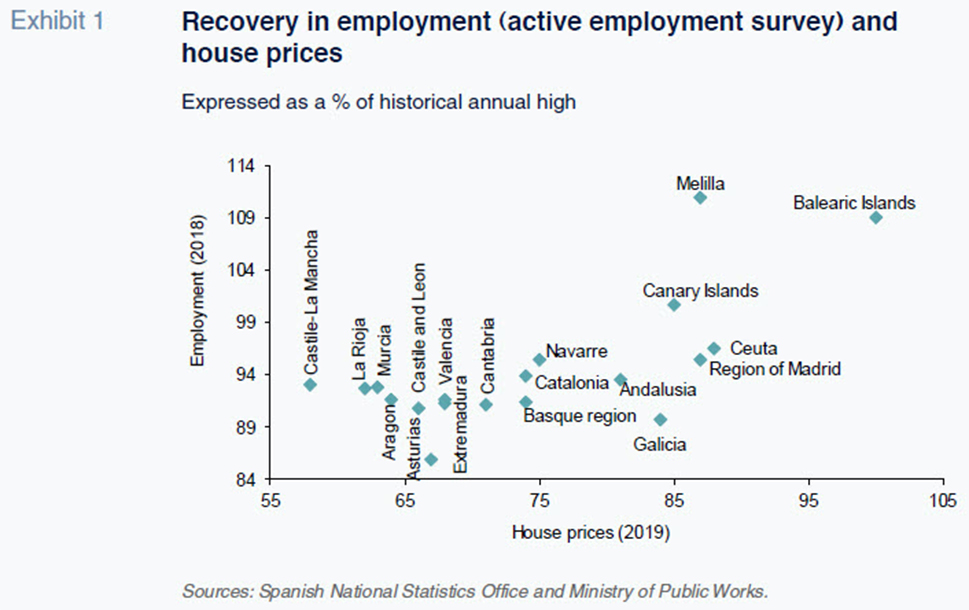

The trend in employment is very closely aligned with the changes in population and a vital factor in the decision to purchase a home. As shown in Exhibit 1, employment has recovered particularly well in the same regions in which prices are closest to pre-crisis levels. And so, in the regions in which price recovery has been stronger than the national average, job creation has similarly been more intense, with the exception of Galicia, as discussed above. Elsewhere, in the regions where price recovery is lagging the national average, job dynamics are also weaker than in the country as a whole, with the exception of Navarre and Catalonia.

In short, with the odd exception, in the areas where population growth and job creation has been strongest, housing prices have recovered more intensely. In contrast, the regions with weaker population and employment dynamics have experienced a weaker recovery in house prices.

Housing affordability

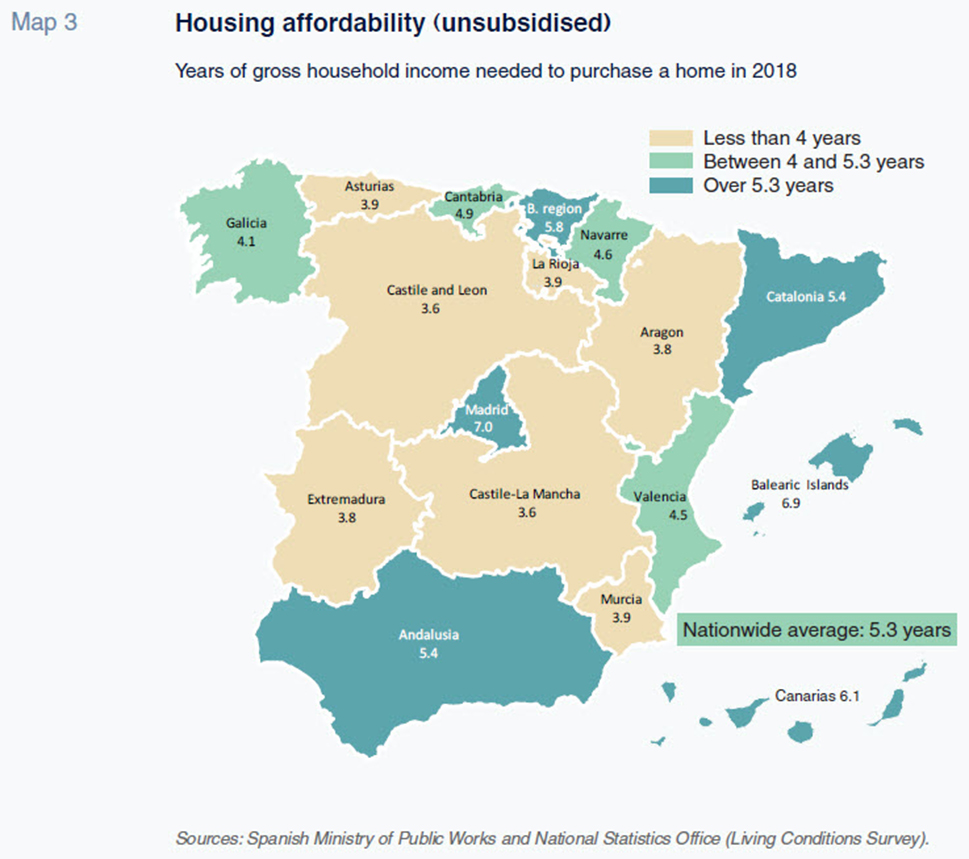

The variables analysed so far provide a snapshot of the recovery in the housing market across Spain. However, it is also important to consider how the housing affordability indicators have fared. One way of quantifying affordability is to divide house prices by average gross household income by region. This provides an estimation of the number of years needed to purchase a home if all household income is earmarked for just that purpose.

In 2018, the national average for the number of years of gross household income it took to purchase a house was 5.3. As shown in Map 3, the regions topping this particular ranking that year were Madrid, the Basque region, Catalonia, Andalusia and the Canary Islands. Conversely, in the inland regions –now dubbed ‘Unpopulated Spain’– and the coastal regions of Murcia and Asturias, that indicator stood at less than four years. The rest of the regions fell somewhere in between.

In 2018, Spanish households needed on average 1.2 years less income to buy a house than at the height of the boom. All Spanish regions are below peak ‘non-affordability’ by more than one year, with five regions off this peak amount by more than two years. However, in the Canary Islands and Madrid, the affordability indicator is within one year of the peak reading.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the housing market recovery in the various regions of Spain yields the following noteworthy conclusions:

- House prices in Spain have recovered significantly over the past years and currently stand at a little over 80% of pre-crisis peak levels. However, there are considerable differences from one region to the next. There are still 22 provinces in which price recovery remains at less than 65% of peak levels, while in nine, prices have outperformed the national average.

- The recovery in transaction volumes has lagged the recovery in prices. Volumes currently stand at just over 60% of peak levels and similarly present considerable differences across the various provinces. It is worth highlighting the weak new housing construction figures, as the market is still digesting the legacy stock of unsold housing left over from the real estate bubble.

- Spain’s population declined in the wake of the crisis and has since gone on to recover gradually, albeit growing at lower rates than those observed before the financial crisis. Nevertheless, there are 19 provinces in which the population is at an all-time high. With the odd exception, those regions where population and employment growth have been strong have seen more intense house price recoveries.

- Housing affordability has improved since the height of the boom in all regions, even those in which price recovery has been most dynamic, putting prices at close to pre-crisis levels.

Lastly, although it looks as if the housing market as a whole will experience a soft rather than a hard landing, the differing rates of recovery from one region to the next highlight the important structural changes in Spanish society that could pose future challenges.

Notes

Data compiled by national appraiser TINSA for all provincial capitals except Burgos, Soria, Toledo, Tarragona, La Coruña, Lugo, Orense and Logroño.

References

ALVES, P. and URTASUN, A. (2019). Recent housing market developments in Spain. Economic Bulletin of the Bank of Spain, Vol 2/19.

CARBÓ, S., CUADROS, P. and RODRÍGUEZ, F. (2019). Spain’s current slowdown: Reduced real estate and financial risks Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Volume 8(6), November 2019.

OCAÑA, C. and TORRES, R. (2019). The Spanish housing market: Current situation and short-term outlook, Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Volume 8(6), November 2019.

REGISTRADORES DE ESPAÑA. (2019a). Property registry statistics 2018.

– (2019b). Property registry statistics 3Q 2019.

Fernando Gómez Díaz. Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas