The Spanish economy in 2019 and forecasts for 2020-2022

While Spain’s growth is projected to slow to 1.5% in 2020, supportive international factors should begin to take effect during the second half of the year, underpinning a recovery in 2021 and 2022. That said, risks remain in the form of a persistently high budget deficit and global trade tensions.

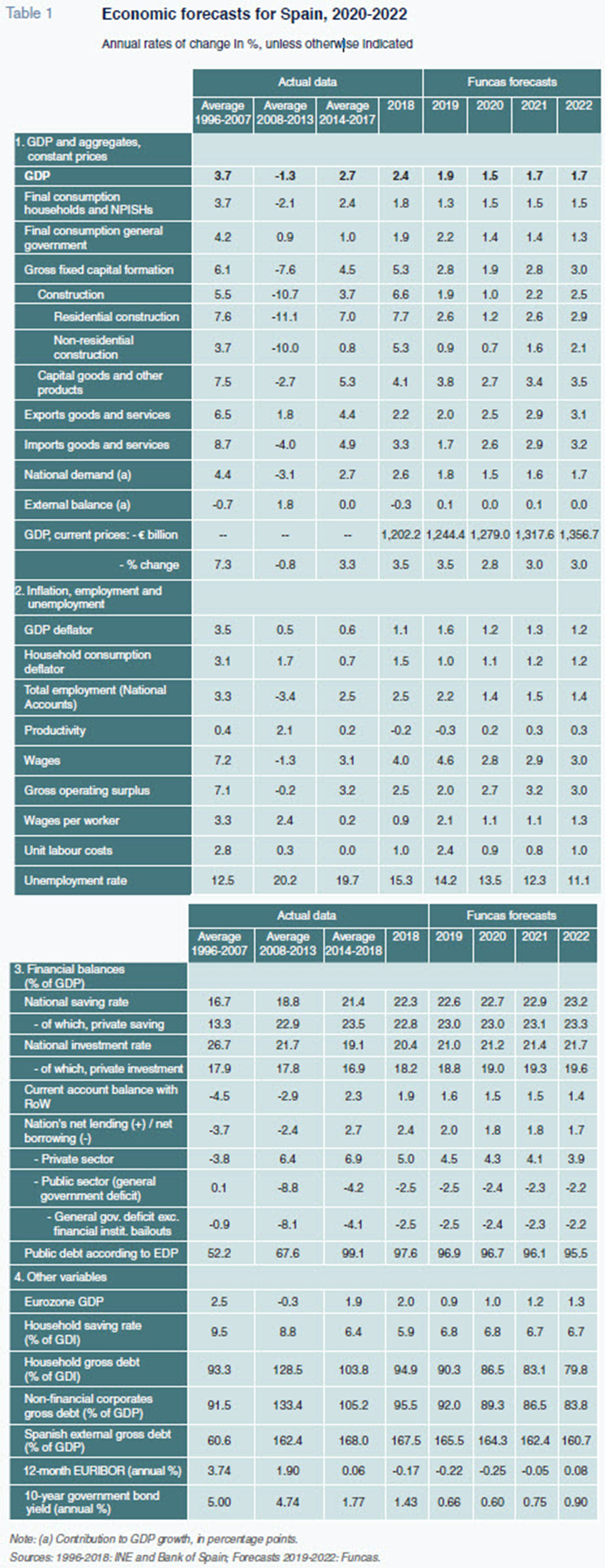

Abstract: The Spanish economy registered growth of 1.9% in 2019, in line with October forecasts. The forecast for growth in 2020 is 1.5%, shaped by a slowdown in housing investment, public consumption and exports, the latter marked by a climate of heightened trade tensions and a slowdown in trade in manufactured products. Based on an improved global backdrop (i.e., relaxation of US/China trade tensions, expansionary monetary –and in some cases fiscal– policies), the slowdown in Spain could hit bottom during the second half of the year, facilitating a modest rebound in 2021 and 2022 to 1.7%. Under those conditions, Spain would create close to 800,000 jobs over the next three years, fuelling a drop in the unemployment rate to 11.1% in 2022. A key concern lies with the public deficit, which, pending specification of the new government’s economic policy, is barely expected to come down during the projection period, at an estimated 2.2% of GDP in 2022. In any event, these forecasts may be subject to revisions once the 2020 budget is approved and there is more clarity over the new government’s economic policy agenda. However, the biggest downside risk lies abroad, particularly with the prevailing trade tensions which, if they were to intensify, could hurt the economic outlook.

The Spanish economy in 2019

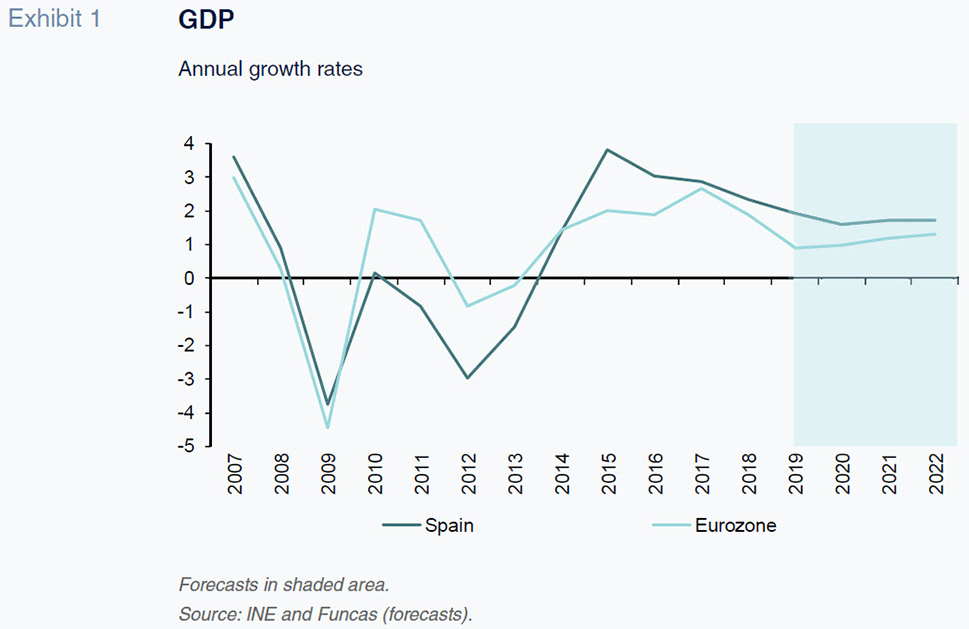

Although not all the fourth-quarter indicators are available, it is expected that Spain will have grown by 1.9% in 2019, down from 2.4% in 2018 (Exhibit 1). That figure, although in line with Funcas’ October forecasts, is below that of the Funcas’ panel of consensus forecasts at the end of 2018, of 2.2%. Note, however, that those consensus forecasts were prepared on the basis of the then prevailing national accounting figures, which were revised significantly downwards in September 2019.

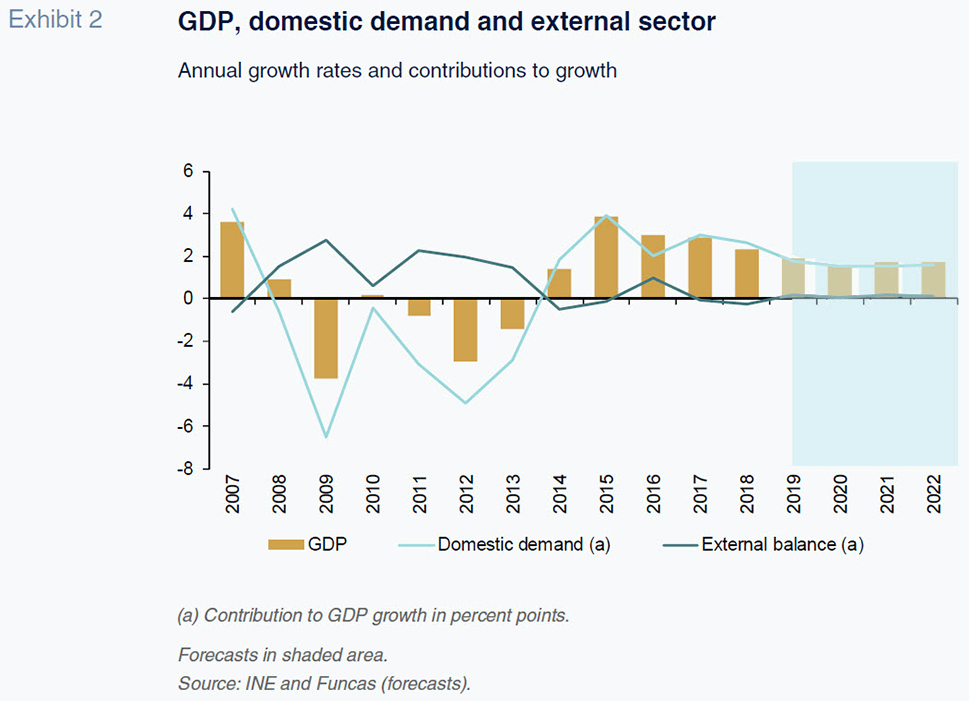

The slowdown was driven entirely by domestic demand, as foreign trade made a positive contribution to growth for the first time in three years. Growth eased across all components of domestic demand, except for public consumption, which accelerated (Exhibit 2).

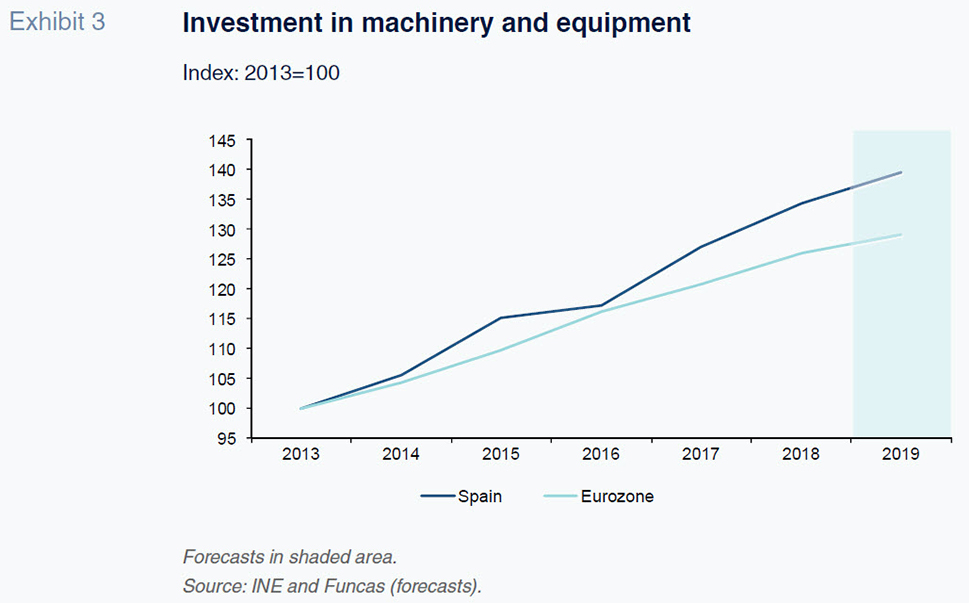

It is worth highlighting the resilience of investment in capital goods, especially given the uncertainty felt globally. Growth in this heading, albeit lower than in 2018, was above the eurozone average, despite the fact that growth in domestic demand trailed that of the eurozone. The dynamism of investment in capital goods in Spain has been a persistent trait since the start of the recovery (Exhibit 3).

Growth in goods exports also lost momentum, virtually stagnating in 2019. In contrast, exports of services other than tourism, registered sharp growth. Imports, on the other hand, slowed by more than exports. In fact, the low growth in imports throughout 2019, which was well below the level derived from applying the usual rates of elasticity with respect to final demand, was one of the economy’s defining characteristics last year. For all those reasons, exports grew by more than imports, so that trade made a positive contribution to GDP growth, having detracted from that growth during the two previous years.

Sector-wise, one of the most surprising trends was the slump in the construction sector, which contracted during the second half. Similarly noteworthy was the continuation of the pattern already observed last year, and common throughout the eurozone, of divergence between the relative weakness of the manufacturing sector, which eked out growth of just 0.5%, and the services sector, which expanded by more than 2.5%. The fact that the manufacturing sector’s weak performance did not spill over to services may be attributable to the fact that the former has continued to create jobs despite its scant growth.

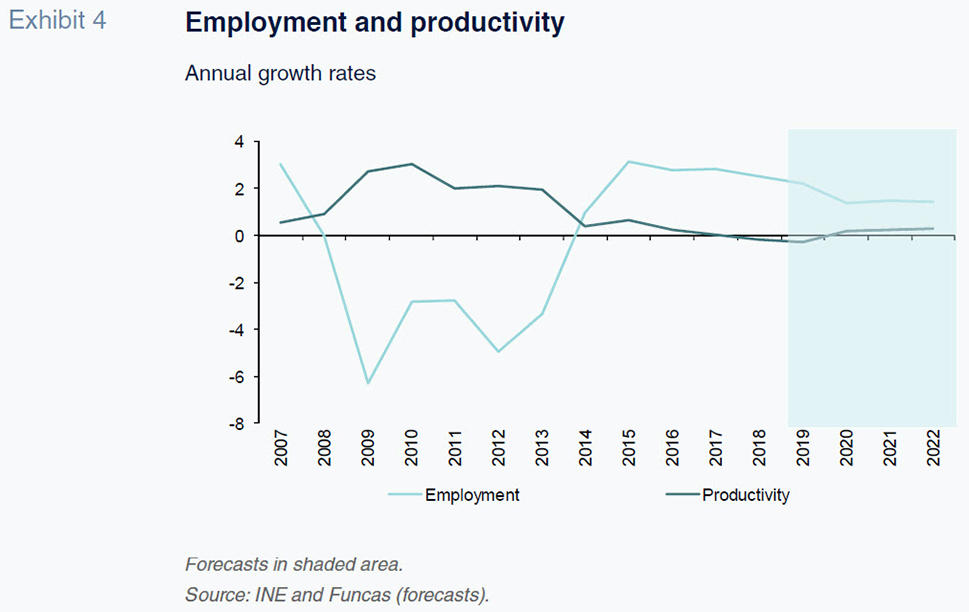

Nevertheless, job creation eased in all sectors in 2019. In parallel, the downtrend in unemployment stalled considerably, slowing more intensely than job creation due to growth in the labour force following higher inflows of immigrants. The average annual rate of unemployment in 2019 is estimated at 14.2%.

Wages increased by around 2%, the highest rate since 2010, in part due to discretionary measures, such as the increases in the minimum wage and public sector pay, as well as wage increases negotiated under the umbrella of collective bargaining. Productivity, meanwhile, the weak link in the recovery of recent years, deteriorated, such that unit labour costs sustained their fastest growth since 2008 (Exhibit 4).

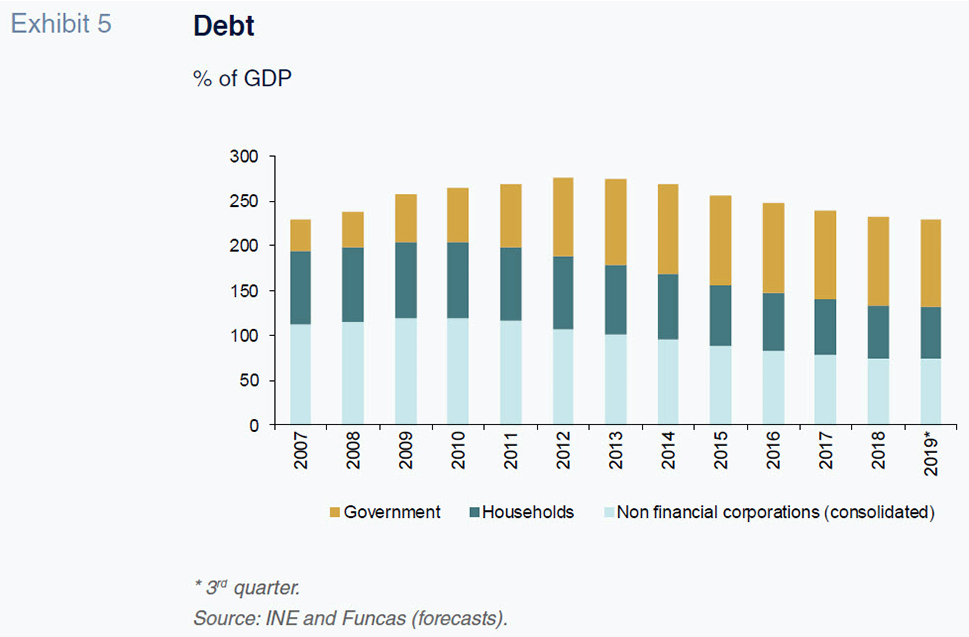

Following the review of the national accounting figures, the household savings rate for 2018 was revised upwards to 5.9% of gross disposable income, an increase from 5.5% in 2017. The data as of the third quarter of 2019 suggest that this metric has continued its upward trajectory, rising to just under 7%. That has enabled a recovery in the household sector’s net lending position from virtually zero in 2017 and 2018 (figures revised upwards from negative numbers) to 0.5% of GDP in 2019. The net flow of new loans for this sector was positive in 2018 for the first time since 2010 (i.e., new loans exceeded repayments), a trend that continues into the third quarter of 2019. Nevertheless, the nominal value of household debt and the resulting leverage rate continued to decline. Household finances, therefore, remain solid, although the deleveraging process may be nearing its end (Exhibit 5).

Spain’s non-financial corporates also presented a net lending position. This marks the continuation of a trend first observed in 2009, though this figure now stands at less than 2% of GDP as of 2019. Despite generating a considerable financial surplus, the non-financial corporates are no longer reducing their volume of nominal debt. However, their borrowings as a percentage of GDP continue to fall.

The public sector deficit is expected to come in at 2.5% of GDP in 2019. The slowdown in public revenue as a result of the lower growth in GDP was not accompanied by an equivalent moderation in spending growth. Instead, public spending remained buoyant with public sector pay increases and hiring, as well a growth in expenditure on pensions. The upshot was a deterioration in the primary deficit (net of interest payments), interrupting the downward trend initiated in 2010.

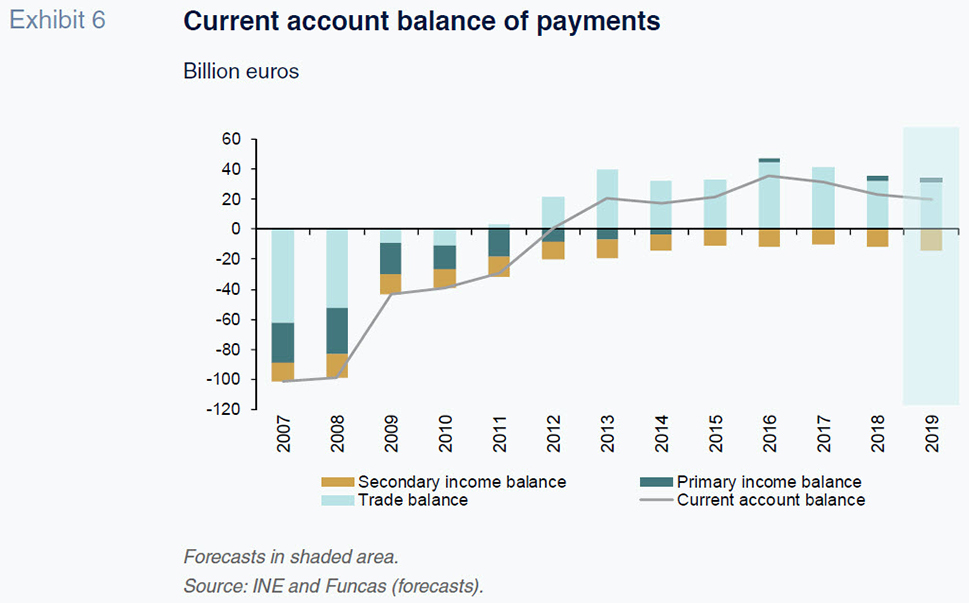

The 2018 balance of payments figures were revised upwards considerably, such that the overall surplus increased by one whole percentage point to 1.9% of GDP. This solid performance is a fundamental part of Spain’s ability to continue the reduction in its foreign borrowings. In 2019, the surplus narrowed, due mainly to growth in the income deficit, to around 1.6% of GDP, still comfortably in positive territory (Exhibit 6).

Forecasts for 2020-2022

The slowdown is expected to continue in coming quarters, in line with the outlook for trade, which is shaped by weak international markets. Those markets are barely expected to grow until mid-2020 as a result of trade tensions, the cooling of the Chinese economy and the slump in manufacturing, particularly the automotive sector. During the second half of the year, relaxation of the trade war between the US and China, coupled with monetary stimulus measures from the main central banks and an element of fiscal easing in some countries, such as Germany and France, should begin to take effect, underpinning a slight recovery in 2021 and 2022.

That profile of weak growth marked by global uncertainty for much of this year, followed by a rebound, is echoed in the main international organisations’ current forecasts. In its latest set of projections, the IMF expects global GDP growth of 3.3% in 2020, down 0.1 percentage points from its last estimate, and of 3.4% in 2021, down 0.2 percentage points. In the eurozone, Funcas, in line with a majority of analysts, is projecting growth of 1% in 2020 (down 0.1pp from 2019), followed by slightly stronger performance thereafter.

For Spain, pending further specifics on the direction of the new government’s economic policy, the projections assume the carry-over of prior-year budgets, albeit with a few adjustments, such as pension and public pay increases and advance payments to the regional governments.

The trends in the global and European economies, coupled with the direction of fiscal policy, will shape Spain’s economic performance. We are forecasting GDP growth of 1.5% in 2020, which is lower than the 2019 figure and unchanged from our previous estimate. We expect the slowdown to be driven by slower growth in investment, particularly in the construction sector, and less buoyant public consumption. The slight uptick in private consumption is attributable to the expectation that the savings rate will stabilise (in 2019, Spanish households increased their savings as pent-up demand was depleted), albeit not by enough to fully offset the slowdown in the other components of domestic demand.

Foreign trade is expected to reduce its contribution to growth in 2020, due to: (i) export weakness (exports are expected to grow at about half of the pace registered during the recovery, as a result of the slowing growth in global trade); and, (ii) growth in imports more in line with the trend in demand (based on the elasticity as estimated by Funcas), after having expanded at a lower rate in 2019 as a result of exceptional factors.

The anticipated improvement in the external environment towards the end of the year, albeit less intense than previously estimated, will have a positive effect in 2021. For that year we are forecasting GDP growth of 1.7%, down slightly from the 1.8% we estimated in October. Driven by the rebound in exports, foreign trade is expected to make a positive contribution to growth. Investment, particularly in capital goods, the element of domestic demand most responsive to the exports climate, should also recover. Private consumption is forecast to grow in line with disposable household income, while public consumption would repeat the performance of 2020. More of the same is expected for most demand components in 2022, leaving GDP growth at around its potential.

The positive growth differential with the rest of the eurozone suggests that Spain will continue to record a solid current account surplus throughout the projection period. That would mean that, underpinned by a favourable competitive position, the Spanish economy would have notched up consecutive, albeit waning, external surpluses throughout an entire decade, an unprecedented achievement.

Job creation is expected to lose momentum as a result of the economic slowdown. Nevertheless, the economy would still generate close to 800,000 net new jobs over the next three years (in full-time equivalent terms), thus bringing the unemployment rate down to 11.1% in 2022. That year, 19.1 million people would be in work, which would still be half a million shy of the pre-crisis peak. Thanks to the reversal of migration flows, with more arrivals than departures since 2018, the working-age population is expected to increase by 300,000 by 2022.

Wage growth is projected to lag that of 2019, which was heavily influenced by the hike in the minimum wage. That, coupled with modest productivity gains, should translate into moderate growth in unit labour costs, but not enough to erode Spain’s competitiveness.

The main concern lies with the public deficit, which, in the absence of new policy-making, is barely expected to come down during the projection period. We are forecasting a deficit of 2.4% in 2020, despite the downward trend in borrowing costs in the current low-rate environment. The deficit is expected to dip to 2.2% in 2022. As a result, public debt would decline marginally as a percentage of GDP.

Risks and opportunities

The international environment remains the primary risk factor. The recovery anticipated from the second half of this year depends largely on developments in trade negotiations –the scope for agreements between the US and China– and an improvement in the investment climate. In Europe, the forecasts assume that the UK’s exit from the EU will be orderly, although the details of the new regime of bilateral trade agreements remains shrouded with uncertainty. Lastly, the forecasts presented in this paper were made assuming oil prices remain stable at around $65 per barrel of Brent. However, any intensification of the geopolitical conflicts in the Persian Gulf (which should not be ruled out) would have an immediate impact on the markets and would weigh on the Spanish economy.

On the upside, the deployment of new reforms designed to reduce economic and social deficits, in addition to improving long-term growth prospects, would have a positive impact on confidence in the short-term and help shore up growth throughout the projection period.

Raymond Torres and María Jesús Fernández. Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas