The consequences of graduating in a recession in Spain

Rigidities in Spain´s labour market appear to increase the negative impact on workers´ earnings for those entering the market in times of recession. While the much needed recent labour market reform in Spain has changed some important aspects of the Spanish labour market, it has done little to reduce segmentation, decreasing the likelihood of improving this situation for new entrants in Spain during the latest financial crisis.

Abstract: The undesirable effects on workers´ earnings from increases in unemployment are a function of both the workers´ education level and the characteristics of labour market institutions. Although there is variation across skill levels, generally, workers graduating at a time of high unemployment feel a greater negative impact on wages in the case of inflexible labour markets, such as that of Spain, relative to flexible ones. Moreover, economic conditions at the time of labour market entry and for the subsequent 10-15 year period are also an important factor, where once again, workers in inflexible labour markets are more adversely affected by entry during recessions. In addition, in the case of Spain, the effects of conditions at entry on earnings are driven more by greater difficulty to find employment than decreases in the level of wages. Finally, the negative effects of recession on workers in Spain (in particular for college graduates) appear to have been exacerbated following the 1984 reform, which increased reliance on fixed-term contracts.

Introduction

In their recent work published in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Oreopoulos et al., 2012, explain that, “the long-term impact from graduating in recessions can depend on how recessions affect the quality and availability of initial job opportunities, wage adjustments within firms, knowledge about workers’ productivity by potential employers, and human capital accumulation.” Hence, recent findings based on flexible labour markets in the US and Canada (Kahn, 2010; Oreopoulos et al., 2012, and Altonji et al., Forthcoming 2016) may not necessarily apply to rigid and segmented labour markets, such as those in Spain.

The extent of damage caused by unemployment depends on both workers’ education levels and labour market characteristics. Among college graduates in flexible labour markets, the evidence indicates initial wage losses ranging between 2.5 and 6 percent for a 4 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate, the average increase in a typical US recession. Although the effect eventually fades away, the wage reduction adds up to a loss of between 5 and 18 percent of cumulated earnings over the first 10 years for Canada and the US—see Oeropolous et al. (2012) for findings on Canada and Kahn (2010) and Altonji et al. (Forthcoming 2016) for findings on the US. In contrast, Kondo (2008), Genda et al. (2010) and Hershbein (2012) estimate small and temporary negative wage losses for low-skilled workers in the US, suggesting that this market resembles a spot labour market.

In more rigid labour markets, large and persistent earnings and employment effects are found among both lower- and higher-educated workers, as shown by Raaum and Roed (2006) for Norway, Genda

et al. (2010) for Japan, and Brunner and Kuhn (2014) for workers with vocational training in Austria. For France, Gaini

et al. (2014) find that an increase in the unemployment rate when leaving school lowers the employment rate of new entrants during the first 3 years, but has no significant wage effects.

[1] For Germany, Biewen and Steffens (2010) find negative effects of labour market entry conditions

on wages of low-and medium skilled workers, but these negative effect fade away within 3 years.

In this article, drawing from the work in Fernandez-Kranz and Rodriguez-Planas (2015), we analyse the long-term consequences of graduating during a recession in Spain, using Social Security records from the 2008 Continuous Sample of Working Histories (hereafter CSWH). In particular, we focus on Spanish males that graduated from high school, vocational training, or college between 1979 and 1991, and follow their labour market outcomes from a year after they graduated up to 2008. Our sample is unusually large, comprising 4,878,043 quarterly-individual level observations, 2,152,300 (or 44%) of which are high-school graduates, 1,905,192 (or 39%) of which have vocational training, and 820,551 (or 17%) have a college degree. Understanding how the business cycle at labour market entry affects the employment careers of male workers in Spain is a step forward for designing policies to cope with the currently high unemployment rates.

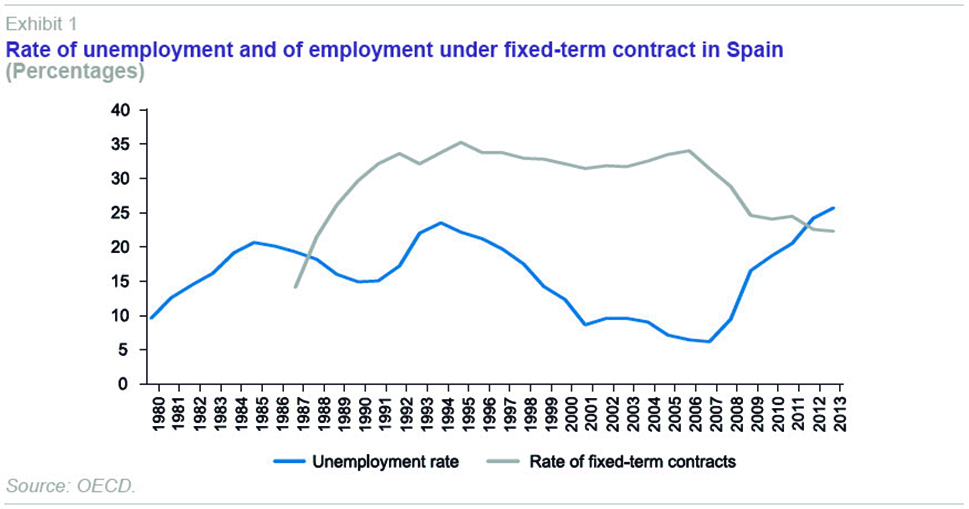

MethodologyThe empirical strategy is to compare the employment and career paths of individuals that graduated at different moments in time and across different regions, hence under very different economic conditions. To measure entry conditions, in line with convention, we use the regional unemployment rate one year before the individual finished his studies. Our period of labour market entry (between 1980 and 1992) includes both a recession with unemployment increasing from 11% in 1980 to 22% in 1985, and an economic expansion lowering unemployment back to 16% in 1992 (shown in Exhibit 1).

Summary of main findings

We find that graduating in a time of high unemployment in Spain results in substantial and persistent annual earnings losses. The average effect over a 10 year period of an 8 percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate at entry – the average shift from boom to recession – is a 9.6%, 12.5% and 6.4% decrease in annual earnings for high-school graduates, workers with vocational training, and college graduates, respectively. For college graduates, the negative effect persists for 5 years, and for those without a college degree, it persists for 7 years. For those without a college degree, the main reason for losses is the poor likelihood of finding employment. For college graduates, earnings losses are explained by both a lower likelihood of being employed and a lower probability of working under a permanent contract. These results are in sharp contrast to findings in more flexible labour markets, such as the US and Canada, where the effects on hours worked and earnings (conditional upon working) are modest for all education groups. The results have been subject to a variety of sensitivity tests and do not seem to be driven by factors, such as cross-provincial mobility, employee’s unobserved attributes, and graduation decisions.

We also analyse the dynamic effects and find that economic conditions are important

both at the beginning of one’s career and during the first decade (for high-school graduates) or the first fifteen years (for workers with vocational training and college graduates) following entry, suggesting that workers who entered the labour market during economic downturns do worse in the long term because they benefit less from the following economic expansion than those who joined the labour market during the economic boom. Hence, labour market entry conditions continued to have a strong effect on Spanish college graduates’ careers even 10 or 15 years

after they began. This finding contrast with the situation in flexible labour markets (Oreopoulos

et al., 2012). Similarly, another finding that differs from that of more flexible labour markets is the lack of evidence that firm mobility helps in the catch-up process among college workers.

[2] While poor labour-market entry conditions increase the mobility of college workers across firms and industries, evidence suggests that this is the result of churning across fixed-term contracts, as opposed to moving to better jobs.

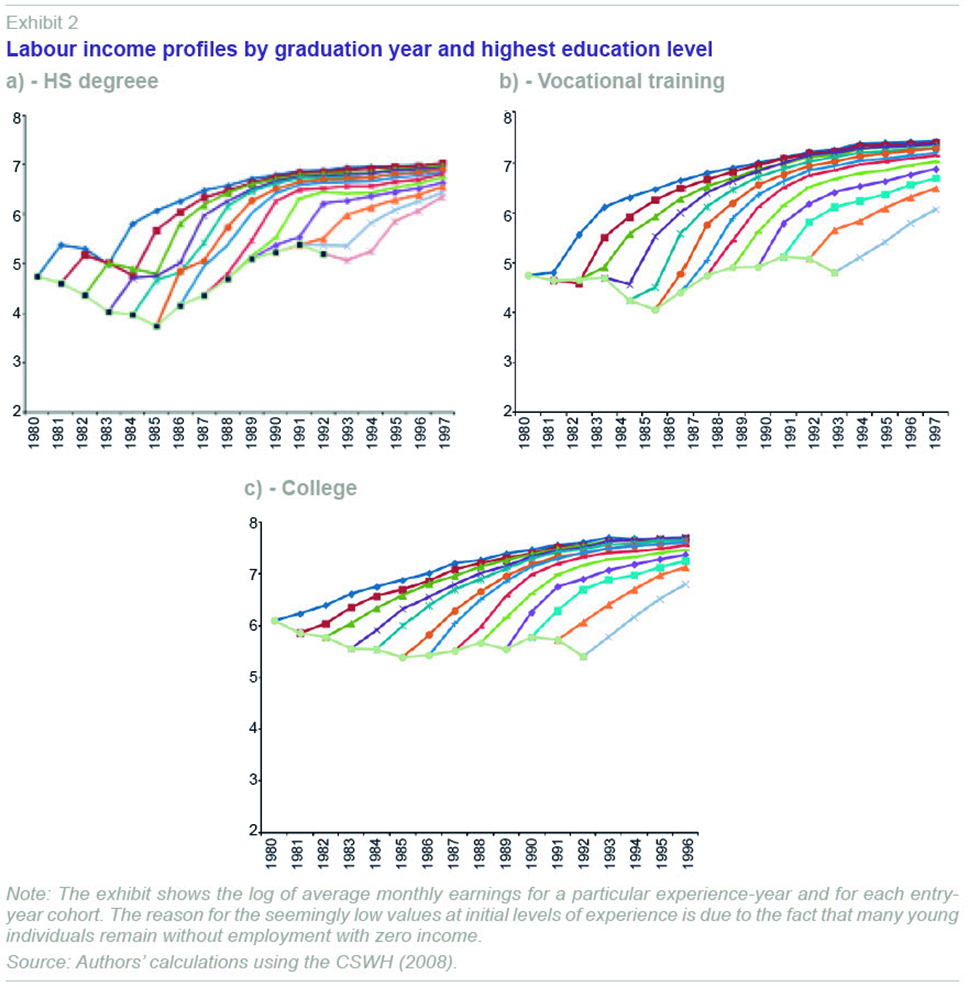

Labour income profiles by year of entry

Exhibit 2 shows the general experience profiles in annual earnings for our baseline Spanish data by highest education level completed. For high-school graduates and individuals with vocational training, we observe sharp and sizeable differences in starting earnings across graduation cohorts, with those entering between 1981 and 1987 (for high-school graduates) and 1983 and 1986 (for those with vocational training) having lower annual earnings. While fluctuations of starting earnings across graduation cohorts are also observed among college graduates, they are smoother. Interestingly, Exhibit 2 shows a clear pattern of convergence for all education groups, suggesting that initial differences in starting conditions tend to fade over time and become negligible for all groups around 7 years after entry. In what follows, we will analyse the mechanisms that explain these earnings gaps and the convergence patterns in each education group.

Effects of entry conditions on annual earnings

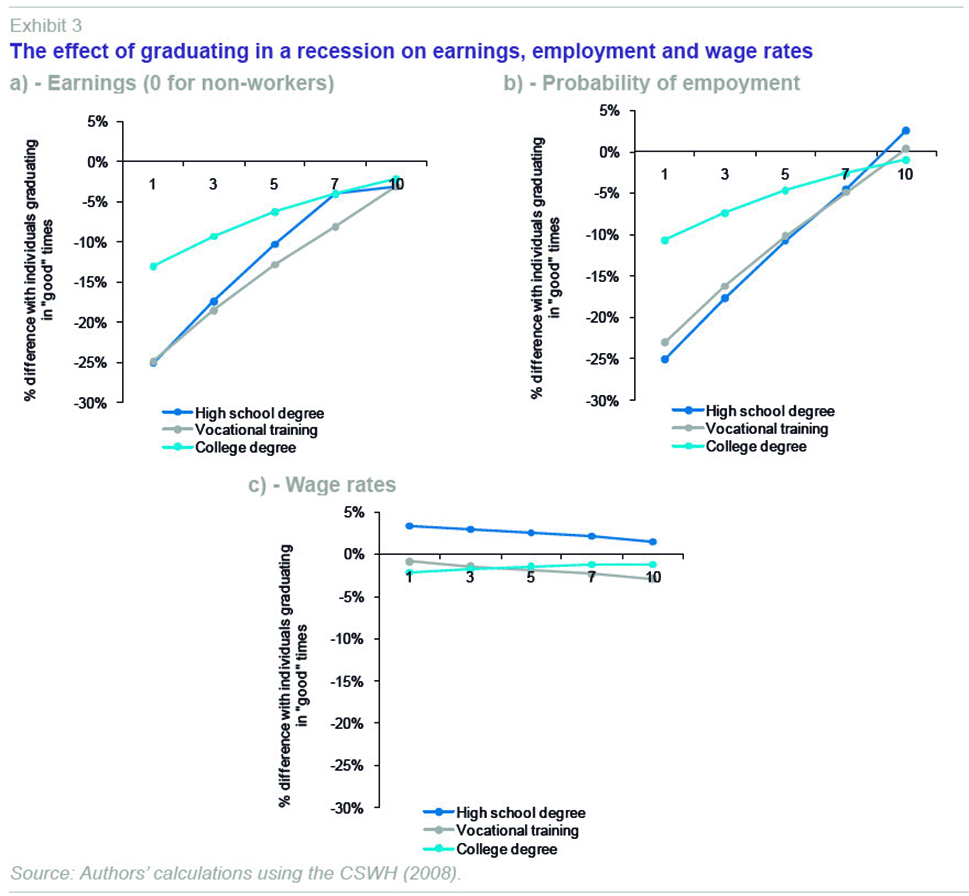

Exhibit 3 shows estimates of the effects of labour market entry on annual earnings by highest education level. Average earnings are defined as average labour income including non-workers, for which labour income is set to zero. The exhibit shows the effect of an 8 percentage points increase in the provincial unemployment rate (the average increase during a typical recession in Spain) at labour market entry at different years of potential experience (at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 years experience).

The shifts due to experience profiles are shown in Panel (a) of Exhibit 3. They show that the negative shock is more persistent for individuals without a college degree. The effect of the negative shock at labour market entry is a decrease in earnings of 25.1% and 24.9% during the first year in the labour market for high-school graduates and workers with vocational training, respectively. The effect of the shock decreases to 17.4% and 18.5% at experience year 3, and further to 10.3% and 12.8% at experience year 5, respectively. For both groups, the negative effect of the shock on earnings fades away at experience year 10. For college graduates, the full effect of an increase of 8 percentage points in the unemployment rate fades away within 7 years. College graduates experience a 13% decrease in earnings during the first year in the labour market, a 9.3% decrease at experience year 3, and a 6.3% decrease at experience year 5. All of these effects are statistically significantly different from zero at the 99%, 95%, and 90% level, respectively. After 7 years, the effect becomes smaller and is no longer statistically significantly different from zero.

Panel (b) in Exhibit 3, shows estimates of the effects of labour market entry on the likelihood of being employed by highest education level. Estimates in Panel (b) resemble closely those in Panel (a) for all education levels, and their magnitude ranges between 75% and 100% of the effects found in Panel (a). Hence, consistent with studies analysing rigid labour markets (Raaum and Roed, 2006, and Genda et al., 2010), we find that the effects of conditions at labour market entry on annual earnings (shown in Panel a) are driven by differences in the likelihood of being employed, not by differences in the level of wages.

We turn now to the results of wages, shown in Panel (c). These estimates are obtained using only employed individuals. They give guidance on whether differences in monthly wages conditional on working drive any of the observed negative and persistent effects of entering the labour market during an adverse shock. However, as labour market entry conditions affect employment, results from this analysis need to be taken with caution because of sample selection. Overall, we find modest impacts of labour-market entry conditions on monthly earnings, which is not surprising given the extent of wage rigidity in the Spanish labour market before 2008, implying that most of the effects found in Panel (a) are driven by employment. More specifically, for high-school graduates, we observe a small, but statistically significant, positive effect on monthly wages. This small positive effect is consistent with the idea that during recessions there is substantial job shedding with lower quality jobs being destroyed and only higher quality jobs surviving. Therefore, those observed working do so at higher than average wages.

The effect of entry conditions before and after the 1984 reform

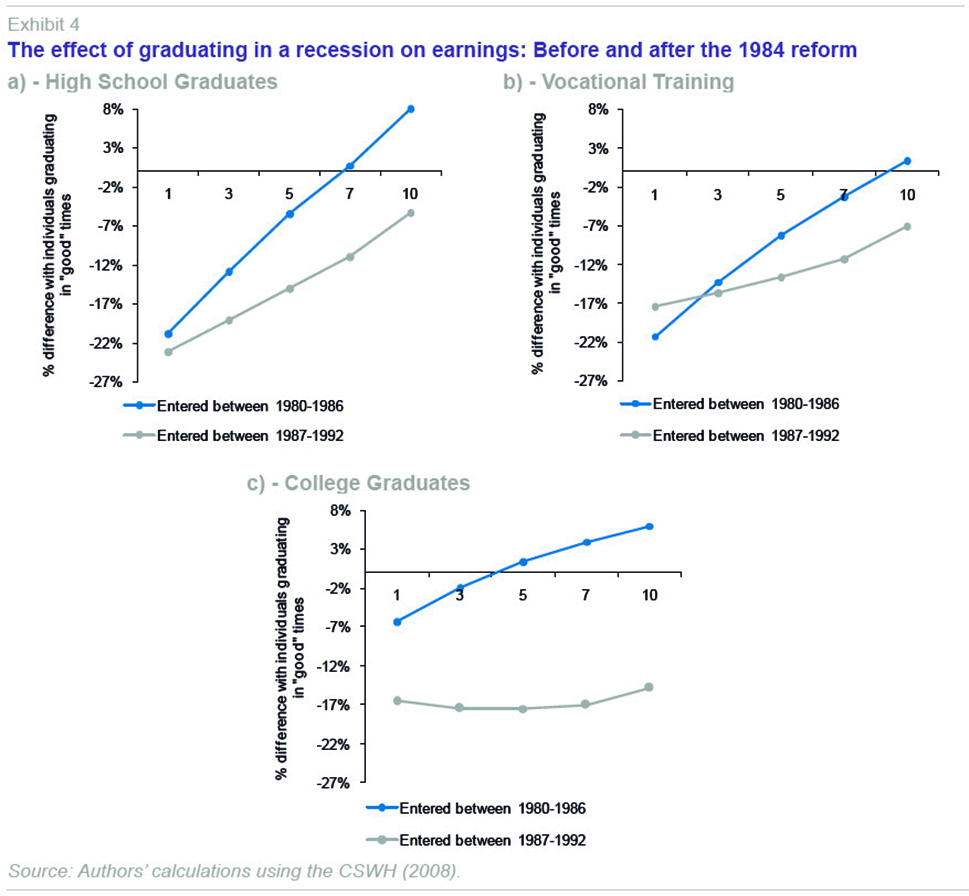

Exhibit 4 presents estimates by whether labour market entry occurred after 1984, one year after fixed-term contracts had first been legalized in Spain. In theory, the effect of the 1984 reform is ambiguous. On the one hand, the existence of fixed-term contracts could have a positive effect on those who enter during recessions by offering them the chance to start in a temporary job, with the hope that later the worker would transition into a job with a permanent contract. To put it differently: temporary contracts could act as a stepping stone into employment and better jobs for those who faced difficult conditions at entry. However, the generalization of fixed-term contracts could lead to the segmentation of the labour market, with those under temporary contracts trapped in poor and precarious jobs for long periods of time.

The results of this analysis need to be taken with caution, since there are possible confounding factors that could explain the differences in the results between the periods before and after 1984. Exhibit 4 suggests that the detrimental effects of entering the labour market during a recession are much larger and much more persistent for those cohorts who entered after the labour market reform that legalized fixed-term contracts. For college graduates, we observe statistically significant effects of a negative shock on annual earnings if they entered the labour market after 1984. For those without a college degree, the negative shock is also observed prior to the legalization of fixed-term contracts. The effect is not only more negative the initial years after entry, but becomes more persistent, especially for individuals with a college degree, suggesting that fixed-term contracts, rather than acting as a stepping stone into better jobs, trap workers in the precarious segment of the labour market.

[3]

Also consistent with this idea, we find that ten years after entry, individuals with a college degree that graduated in a recession have a 10% higher probability of holding a temporary contract than individuals that graduated during an economic boom and change firms and industries more often even though these changes do not result in better jobs or higher wages. Instead, individuals with a high school degree face the same probability of holding a temporary contract, regardless of whether they graduated during a recession or during an economic boom. Since lower educated individuals tend to work under temporary contracts with a high probability in general, but college graduates do not, the deteriorating effects of poor entry conditions are more important for the latter group once temporary contracts became a dangerous possibility for college graduates who entered the labour market during recessions.

[4]

Final remarks

This article shows the results of an ongoing analysis of the effects of labour-market entry conditions on workers’ careers in a context of both high structural unemployment and segmented labour markets. The evidence presented shows that, in such conditions, workers entering the labour market during a recession experience large and persistent earnings losses, especially if they do not hold a college degree. For lower-educated workers, the effect is driven by a lower likelihood of employment. For college graduates, our results are surprisingly similar to those found by other researchers in more flexible labour markets such as the US and Canada, but the mechanisms are radically different as the negative impact on earnings is driven not by lower wages but instead by a higher probability of difficulties to find employment and of employment under a fixed-term contract.

The present study exploits the variation in entry conditions during the period 1980-1992 and follows individuals up until 2008. This study is useful to extract lessons about the possible career paths of individuals that graduated during the recent financial crisis. However, the 2012 labour market reform has changed important aspects of the Spanish labour market and it will be interesting to see in future years if the negative effects of poor entry conditions are different now compared to previous recessions. Unfortunately, one is led to believe that the negative effects that we find in this study will probably be present also for the current generation of young individuals that graduated during the recent financial crisis. The reason for this is that the 2012 reform did little to modify the segmentation of the Spanish labour market, and once again we see many of the features that characterized our labour market at the outset of past recessions: high levels of unemployment, especially of long duration and amongst youth, and a strong divide between individuals holding a permanent contract and those trapped in temporary jobs, with more than 90% of the newly signed contracts in the past two years being fixed-term contracts.

Notes

Because the authors use national unemployment rates as a measure of labour market entry conditions, their estimates may be biased towards zero due to measurement error.

Oreopoulos et al., 2012 find that the”earnings adjustment process is characterized initially by increased mobility across employers and industries and improvements in the characteristics of the average employer.”

Our findings show that the higher the education level, the greater the impact of the 1984 reform on the effects of entry conditions on future labour market prospects of youth in Spain. This contrasts with Garcia-Perez et al. (2015) findings that the 1984 reform had more negative impacts on lower educated individuals. Our study is different from theirs in that we analyse the impact of business cycle conditions at entry on future career prospects.

Garcia-Perez et al., 2015 use a cohort regression discontinuity design to estimate the effects of the 1984 reform on employment of high-school dropouts. They find that the reform increased their likelihood of working by age 19, but in the long run, it reduced their days worked and earnings.

References

ALTONJI, J.; KHAN, L., and J. SPEER (Forthcoming 2016), “Cashier of Consultant? Entry Labour Market, Field of Study, and Career Success,” Journal of Labour Economics.

BIEWEN, M., and S. STEFFES (2010), “Unemployment Persistence: Is There Evidence for Stigma Effects?,” Economic Letters, 106: 188-190.

BRUNNER, B., and A. KUHN (2014), “The Impact of Labour Market Entry Conditions on Initial Job Assignment and Wages,” Journal of Population Economics, 7: 705-738.

FERNÁNDEZ-KRANZ, D., and N. RODRÍGUEZ-PLANAS (2015), “The Perfect Storm: Effects of Graduating in a Recession in a Segmented Labour Market,” City University New York, Queens College, mimeo.

GAINI, M.; LEDUC, A., and A. VICARD (2014), “A Scarred Generation? French Evidence on Young People Entering into a Tough Labour Market,” EU Commission.

GARCÍA-PÉREZ, J. I.; MARINESCU, I., and J. VALLS CASTELLO (2015), “Can Fixed-Term Contracts Put Low-Skilled Youth on a Better Career Path? Evidence from Spain,” UPO Working Paper, No. 15.12.

GENDA, Y.; KONDO, A., and S. OHTA (2010), “Long-Term Effects of a Recession at Labour Market Entry in Japan and the United States.” Journal of Human Resources, 45(1).

HERSHBEIN, B. (2012), “Graduating High-School in a Recession: Work, Education and Home Production,” B E J Econom Anal Policy, 2012 Jan 31;12(1), Epub 2012 Jan 31.

KAHN, L. B. (2010), “The Long-Term Labour Market Consequences of Graduating from College in a Bad Economy,” Labour Economics, Vol. 17, No. 2: 303-316.

KONDO, A. (2008), “Differential Effects of Graduating During Recessions Across Race and Gender,” Mimeo.

OREOPOULOS, P.; VON WACHTER, P., and A. HEISZ (2012), “Short and Long-Term Career E_ects of Graduating in a Recession,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Volume 4, No. 1: 1-29.

RAAUM, O., and K. ROED (2006), “Do business cycle conditions at the time of labour market entry affect future employment prospects?,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(2): 193-210.

Daniel Fernández Kranz. IE-Business School

Núria Rodríguez Planas. CUNY, Queens College